NOTE: go here to read the full testimony.

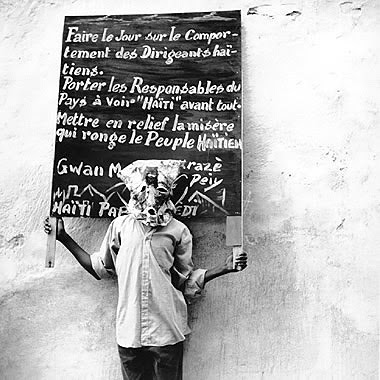

This testimony details the results of neo-liberal and neo-colonialist policies but does not detail how the policies were developed and enforced. For example, prior to the Clinton years, Haiti was self-sufficient in terms of rice production, after Clinton Haiti was dependent on rice imports from the USA. This was not simply a case of corruption or incompetence. When Aristide came to office as president of Haiti, his policies were opposed by the USA government. Aristide was forced out of office at gunpoint by U.S. Marines—TWICE! On the other hand both Papa Doc and Baby Doc Duvalier were supported by the USA government. Haiti poverty is a direct result of international oppression and exploitation aided by, but not caused by, internal tyrants who were kept in office by international forces, the USA government chief among the forces.

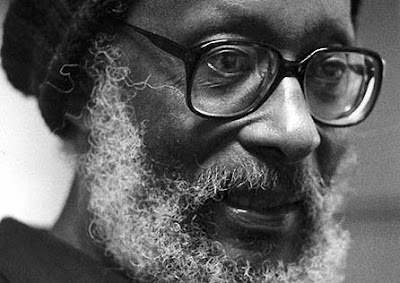

—Kalamu ya Salaam

================================================

Page 1 of 15

TESTIMONY

“Reconstructing to Rebalance Haiti after the Earthquake”

Robert Maguire, Ph.D.

Trinity Washington University

And

The United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

Testimony presented before the Subcommittee on International Development,

Foreign Assistance, Economic Affairs and International Environmental Protection of

the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

February 4, 2010

Thank you for inviting me to testify today.

My first visit to Haiti was in 1974. My first full day in Haiti was the day that Haiti’s

National Soccer Team scored the incredible goal against Italy in the World Cup. That

may not mean much to Americans, but to Haitians it means everything. I have come to

take this coincidence as a sign that there was bound to be some kind of unbreakable

bond between Haiti and me. And that came to pass.

My most recent visit ended on January 10, 2010, two days before the earthquake. In

between, I have visited Haiti more than 100 times, as a US government official working

with the Inter-American Foundation and the Department of State; as a scholar and

researcher, and as a friend of Haiti and its people. I have traveled throughout that

beautiful, if benighted, land. I have met and broken bread with Haitians of all walks of

life. I have stayed at the now-destroyed Montana Hotel. I had dinner there 5 days

before the quake, chatting with waiters and barmen I had befriended over the years. I

speak Creole. I have lost friends and colleagues in the tragedy. I am anxious to share

my views and ideas with you.

Page 2 of 15

In the deep darkness of the cloud cast over Haiti by the terrible tragedy of January 12

there is an opportunity for the country and its people to score another incredible goal,

not so much by reconstructing or rebuilding, but by restoring a balance to achieve a

nation with less poverty and inequity, improved social and economic inclusion, greater

human dignity, a rehabilitated environment, stronger public institutions, and a national

infrastructure for economic growth and investment. And, if that goal is to be scored,

relationships between Haitians and outsiders also will have to be rebalanced toward

partnership and respect of the value and aspirations of all Haiti’s people.

A Country Out-of-Balance

In the five decades that I have traveled to Haiti, I have seen the country become terribly

out-of-balance. Much of this revolves around the unnatural growth of Haiti’s cities,

especially in what Haitians call “the Republic of Port-au-Prince.” In the late 1970s,

Haiti’s rural to urban demographic ratio was 80% to 20%. Today it is 55% to 45%. The

earlier ratio reflected what had been chiefly an agrarian society since independence.

The population of Port-au-Prince in the late 1970’s was a little over 500,000 – already

too many people to be adequately supported by the city’s physical infrastructure. By

then, Haitians from the countryside had already begun trickling into the capital city as a

result Dictator Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s (1957 – 1972) quest to centralize his grip

on power. Under Papa Doc, a ferocious neglect beyond PAP took place, as ports in

secondary cities languished, asphalted roads disintegrated and, in some cases, were

actually ripped-up, and swatches of the countryside were systematically deforested

under the guise of national security or by way of timber extraction monopolies granted

to Duvalier’s cronies. Small farmers were ignored as state-supported agronomists

sought office jobs in the capital.

The only state institutions present in the countryside were army and paramilitary

(Tonton Makout) posts and tax offices – which enforced what rural dwellers told me was

Page 3 of 15

a ‘squeeze – suck’ (pese - souse) system of state predation. With wealth, work and what

passed for an education and health infrastructure increasingly concentrated in Port-au-

Prince (PAP), it was no wonder that poor rural Haitians had begun to trickle off the land

into coastal slums with names like “Boston” and “Cite Simon” (named after Papa Doc’s

wife), and onto unoccupied hillsides and ravines within and surrounding the city.

The trickle turned into a flood in the early 1980’s when the rapacious regime of Jean-

Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier (1972 - 1986) yielded to Haiti’s international ‘partners’ –

governments, international financial institutions, and private investors – who had set

their sights on transforming Haiti into the “Taiwan of the Caribbean.” Political stability

under the dictatorship combined with ample cheap labor and location near the US

formed a triumvirate that shored up this idea, and the “‘Tawanization” of Haiti

proceeded, creating by the mid-1980’s somewhere between 60K and 100K jobs in

assembly factories, all located within PAP. Fueled by a parallel neglect of Haiti’s rural

economy and people, the prospect of a job in a factory altered the off-the-land trickle

into a flood, as desperate families crowded the capital in search of work and the

amenities – education, especially – that the city offered. Between 1982 and 2008, Port-

au-Prince grew from 763,000 to between 2.5 and 3 million, with an estimated 75,000

newcomers flooding the city each year.1

As immigrants piled up in slums, on deforested and unstable hillsides, and in urban

ravines, the opportunity offered by the city became a mirage. Following the ouster of

Duvalier in 1986 when, as Haitians say, “the muzzle had fallen” (babouket la tonbe) and

freedom of speech and assembly returned, factory jobs began to dry up as nervous

investors sought quieter, more stable locations. By the 1990’s, only a fraction of those

jobs remained. Yet the poor continued to flow into the city.

1

Robert Maguire, Haiti After the Donors’ Conference: A Way Forward, United States Institute of Peace,

Washington DC, Special Report 232, September 2009.

Page 4 of 15

Papa Doc’s centralization, combined, under the rule of Baby Doc, with the urban-

centric/Taiwanization policies of key donor countries (including the US) and

international banks had a devastating impact on Haiti. Enacted by a government and

business elite who saw these policies as a golden opportunity to make money, the

internationally-driven Tawanization of Haiti neglected what Francis Fukuyama has

pointed out as the key to Taiwan’s own success: a necessary investment in universal

education and agrarian improvement before investing in factories.2 Haiti’s people were

viewed internationally and by local elites strictly as pliant and ample cheap labor.

Education might make them ornery. Avoid it. Why invest in agriculture when cheaper

food – heavily subsidized imported flour and rice – could feed Haiti’s growing urban

masses? In the late 1970’s Haiti did not need to import food. Today, it imports some

55% of its foodstuff, including 360,000 metric tons of rice annually from the US.3

The folly of these policies was seen in early 2008, during the global crisis of rapid and

uncontrolled commodity price increase, when that rice, still readily available, was no

longer cheap and the urban poor took to eating mud cookies to survive. Another spin-

off of these fallacious policies of the 80’s was political instability. Poor Haitians took to

the streets in early 2008 to protest “lavi chè” (the high cost of living), with the result

being the ouster of the government headed by Prime Minister Jacques Edouard Alexis

who, coincidentally, had just won praise from the US and the International Financial

Institutions (IFIs) for the creation of a national poverty reduction and economic growth

strategy that would serve as a blueprint for developing all of Haiti, and reversing the

long history of rural neglect.

Rural neglect combined with migration to cities, moreover, placed considerable

pressure on those still in the countryside to provide the wood and charcoal the

burgeoning urban population required. Here was a recipe for desperately poor people

2

Francis Fukuyama, “Poverty, Inequality and Democracy: The Latin American Experience,” Journal of

Democracy 19, no. 4 (October 2008).

3

Op.cit, Maguire, “Haiti After the Donor’s Conference”

Page 5 of 15

to further ravish the environment. Today, 25 of Haiti’s 30 watersheds are practically

devoid of vegetative cover.

Port-au-Prince, and other cities, particularly Gonaives, had become disasters waiting to

happen as a result of these developments. The vast majority of the 200,000 who

perished on January 12th were poor people crowded on marginal land and into sub-

standard housing devastated by the quake. The vast majority of the thousands who

died in the floods in Gonaives in 2004 and 2008 were poor people crowded on alluvial

coastal mud flats and in river flood plains. For Haiti’s poor, their country has become a

dangerous place and a dead-end. Is it surprising that Haitians seek any opportunity to

look for life (chèche lavi) elsewhere? As one peasant told me in the 1990’s, ‘we have

only two choices: die slow or die fast. That’s why we take the chance of taking the boats

(to go to Miami)’ (pwan kantè).

Haiti had lost its balance in other ways, particularly in social and economic equity, and in

the ability of the state to care for its citizens. By 2007, 78 percent of all Haitians – urban

and rural – survived on $2.00 a day or less, while 68 percent of the total national income

went to the wealthiest 20 percent of the population.4 During the 29 year Duvalier

dictatorship, Haitian state institutions virtually collapsed under the weight of bad

governance. Following the 1986 ouster of Baby Doc, who, ironically, was lorded with

foreign funds that went principally to Swiss bank accounts, donors were loathe to work

with successor governments – including those democratically elected. Instead, they

chose to funnel hundreds of millions annually through foreign-based NGOs that enacted

‘projects’ drawn up in Washington, New York, Ottawa, etc. and that lasted only as long

as the money did. Haitians, by the early 1990s, were derisively calling their country a

“Republic of NGOs” and by 2008, none other than the President of the World Bank,

4

Maureen Taft-Morales, “Haiti: Current Conditions and Congressional Concerns,” Congressional Research

Service Report for Congress, May 5, 2009.

Page 6 of 15

Robert Zoellick, lamented the cacophony of “feel good, flag-draped projects” that had

proven a vastly inadequate substitute for a coherent national development strategy.5

Without doubt, Haiti was seriously out-of-balance before the earthquake and Port-au-

Prince was a disaster waiting to happen. Many had feared that it would come by way of

a hurricane; rather the earth shook. Now, let us see how we might make a positive

contribution in restoring balance to Haiti so that when, inevitably, the country is struck

by another natural disaster – be it seismic or meteorological – it is less vulnerable and

better able to confront and cope with the disaster.

Rebalancing to ‘Build Back Better’

Allow me to stress two points: we must be fully cognizant of past mistakes, such as

those outlined above; and the key to ‘building Haiti back better’ is to work toward a

more balanced nation with less poverty and inequities, less social and economic

exclusion, greater human dignity, and a commitment of Haitians and non-Haitians

toward these essential humanistic goals. With this, Haiti can also achieve and sustain a

rehabilitated natural environment, stronger public institutions, a national infrastructure

for growth and investment, and relationships between Haitians and outsiders that are

based on partnership, mutual respect, and respect of the value and aspirations of all

Haiti’s people.

What follows are ideas and recommendations based on not only my experience in Haiti,

but on endless discussions/conversations with Haitian interlocutors. In this regard, I

should add that the principal reason for my visit to Port-au-Prince in early January was

to deliver an address on prospects for rebalancing Haiti. That presentation was made to

an audience of 50 or so Haitian civil servants and policy analysts – some of whom I fear

are no longer with us - who gathered in Port-au-Prince at a Haitian think tank. My ideas

were received by them with great and at times animated interest.

5

Robert Zoellick, “Securing Development” (remarks at the United States Institute of Peace conference

titled Passing the Baton, Washington, DC January 8, 2009.

Page 7 of 15

1. Welcoming Dislocated Persons: A de facto Decentralization

Since the quake, some 250,000 Port-au-Prince residents have fled the city, returning to

towns and villages from which they had migrated or where they have family. An

estimated 55,000 have shown up in Hinche in Haiti’s Central Plateau; the population of

Petite Riviere de l’Artibonite has swelled from 37,000 to 62,000; St. Marc’s 60,000, has

swollen to 100,000.6 The flight of Haitians away from a city that now represents death,

destruction and loss might become a silver lining in today’s very dark cloud. If that is to

be the case, however, we – both the government of Haiti and its international partners

– must catch up with and get ahead of this movement. Already underdeveloped rural

infrastructures and the resources of already impoverished rural families are being

stretched. The provision of basic services to these displaced populations is an urgent

priority. If conditions in the countryside are not improved, the displaced will ultimately

return to Port-au-Prince, to replicate the dangerous dynamics of earlier decades.

To catch up and get ahead of this reverse migration, we should support an idea

proffered by the Government of Haiti in Montreal last week: the reinforcement of 200

decentralized communities. As soon as possible, “Welcome Centers” might be stood up

in towns and villages. They can be temporary, to be made permanent later. They can

serve as decentralized ‘growth poles’ that offer multiple services, including relief in the

short term, with health and education facilities attached. Let us not forget that Haiti has

lost many of its schools and among those fleeing the devastated city are tens of

thousands of students. Twenty five percent of Haitian rural districts do not have

schools. And schools that exist outside Port-au-Prince are usually seriously deficient.

The reverse migration we are seeing today offers a golden opportunity to rebalance the

education and health system of Haiti.

The centers can coordinate investment and employment opportunities, as well as state

services including robust agronomic assistance to farmers. Haiti’s planting season is

6

Trenton Daniel, “Thousands flee capital to start anew,” Miami Herald, January 23, 2010; Mitchell

Landsberg, “The displaced flow into a small Haitian town,” Los Angeles Times, February 1, 2010; data from

MINISTAH headquarters in Hinche.

Page 8 of 15

almost here and now more than ever the country needs a bountiful harvest. Displaced

people working as paid labor can reinforce Haiti’s farmers. Infrastructure needs to be

rebuilt – or built for the first time - including schools, health clinics, community centers,

roads, bridges and drainage canals. Hillsides need rehabilitation, particularly with

vegetative cover and perhaps even stone terraces. Providing work for not just the

displaced, but to those they are joining in towns and villages throughout Haiti, will go a

long way toward rebalancing Haitian economy and society, and toward repairing a social

fabric ripped to shreds by decades of neglect and subsequent migration. This is an

opportunity that must be seized.

2. Support the Creation of a National Civic Service Corps

Since 2007, various Haitian government officials and others have been working quietly

on the prospect of creating a Haitian National Civic Service Corps. Citizen civic service is

mandated in Article 52-3 of the Haitian constitution and, even before the quake, the

idea of a civic service corps to mobilize unemployed and disaffected youth seemed

attractive. Now is the time for this idea to take off. As I have recently written, a

700,000-strong national civic service corps will rapidly harness untapped labor in both

rural and urban settings, especially among Haiti’s large youthful population, to rebuild

Haiti’s public infrastructure required for economic growth and environmental

rehabilitation and protection; increase productivity, particularly of farm products;

restore dignity and pride through meaningful work; and give Haitian men and women a

stake in their country’s future. It will also form the basis of a natural disaster response

mechanism.7

If this all sounds familiar, it should: the idea of a Haitian National Civic Service Corps

parallels the same thinking that went into the creation of such New Deal programs as

the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

7

Robert Maguire and Robert Muggah, “A New Deal-style corps could rebuild Haiti,” Los Angeles Times,

January 31, 2010.

Page 9 of 15

We have seen what these programs did to help the United States and its people stand

up during a difficult time.

In the aftermath of the storms that devastated Haiti in 2008, Haitian President Prèval

asked not for charity, but for a helping hand to allow Haitians to rebuild their country.

Today he is making a similar point. Here is more symmetry between the Haiti and the

U.S. As Harry Hopkins, the legendary administrator of the Works Progress

Administration, pointed out: “most people would rather work than take handouts. A

paycheck from work didn’t feel like charity, with the shame that it conferred. It was

better if the work actually built something. Then workers could retain their old skills or

develop new ones, and add improvements to the public infrastructure like roads and

parks and playgrounds.”8 Let’s help Haiti restore its balance by supporting a national

civic service corps that can accomplish the same for Haiti and its people as our New Deal

programs did in the United States decades ago.

To reiterate, as was the case with our New Deal, Haiti’s civic service corps must be a

‘cash-for-work’ initiative. Cash-for-work will inject serious liquidity into the Haitian

economy and stimulate recovery from the bottom-up. Already there are various entities

employing Haitians in a variety of cash-for-work programs. This Monday, for example,

the UNDP announced that it has enrolled 32,000 in a cash-for-work rubble removing

program; a number expected to double by tomorrow.9 Coordination of existing efforts

within an envisaged national program will be essential to maximizing how Haiti can be

built back better – by its own people, with everyone wearing the same uniform.

A special commission, similar to those established by President Prèval in 2007 to engage

Haitians from diverse sectors to study and make recommendations on key issues

confronting his government, might be established to oversee this coordination. (Other

special commissions could be mounted to tackle other topics or needs and as a means

of expanding the Haitian government’s human resource circle.) Such a commission

8

Nick Taylor, American Made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA, (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), p.99.

9

UNDP, “Fast Fact of the Week,” accessed on February 2, 2010 at undp.washington@undp.org

Page 10 of 15

could be enlarged to include representatives of key donors. A central figure like Harry

Hopkins will have to lead the endeavor. Perhaps such a figure could emerge from Haiti’s

vaunted private sector. In any case, let’s avoid a repetition of the cacophony of feel

good, flag-draped projects.

3. Strengthen Haitian state institutions through accompaniment, cooperation and

partnership

At the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on Haiti held last week, witnesses

spoke of the need to rebuild the Haitian state from the bottom up, and of working with

Haitian officials – not pushing them aside. I agree with these points whole-heartedly.

This is not the time to impose governance on Haiti – that is a 19th century idea unfit for

the 21st century. This is an opportunity to help strengthen Haiti’s public institutions, not

to replace them.

As pointed out above, the capacity of the Haitian state, never strong to begin with, has

deteriorated progressively over the past 50 years. In recent years that was due in part

to international policies that circumvented state institutions in favor of private ones –

both within Haiti and from beyond, and left the resource-strapped government virtually

absent in the lives of its citizens. In the aftermath of the quake, we see starkly the

results of the decimation of the Haiti state. The already weak state has been further set

back by the death of civil servants and the loss of state facilities and physical resources.

In this context, the government of President Rene Prèval and Prime Minister Jean Max

Bellerive has taken much criticism for its response – or lack thereof – in the past few

weeks.

It is easy to kick someone in the teeth when he or she is already on the mat. Rather

than swinging our foot, however, we should offer our hand. This is the time of the

Haitian government’s greatest need. Achieving cooperation and partnership, as pointed

out by Canadian Prime Minister Harper at the recently-held Montreal Conference, is the

Page 11 of 15

biggest concern.10 Over the past four years, the Prèval government has won praise

internationally – and among most in Haiti – over its improved management of the affairs

of the state. Political conflict, though still extant, has diminished considerably. Haiti’s

terribly polarized society is a little less polarized today. Moderation and greater

inclusion – not demagoguery and a winner-takes-all attitude – have worked their way

into the ethos of the Haitian political culture. Partnership to strengthen the Haitian

state was on the horizon following the ‘new paradigm for partnership’ agreed to at the

April 2009 Donors Conference.11 Let’s stay that course. Generations of bad governance

and a zero sum political culture are not turned around overnight.

Quietly, but steadily in the post-quake period, the Haitian government has been picking

itself up by its bootstraps beyond the photo-ops and glare of the cameras to

reassemble, and then to reassert, itself.12 Still, given the magnitude of this catastrophe,

the government is overmatched. Any government would be. This is not the time to cast

aspersions. It is the time to work in partnership and to accompany Haitian leaders

through their time of loss and sorrow, into a more balanced and better future.

4. Get Money into the Hands of Poor People

In 1999, Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto estimated that there was $5.2 billion in

‘dead capital’ in Haiti, shared among 82 percent of the population. Of this sum, $3.2

billion was located in rural Haiti. This amount dwarfed by four times the total assets of

Haiti’s 123 largest formal enterprises. 13 This capital, principally in the hands of poor

people in the form of property, land, and goods, is considered ‘dead’ because it cannot

be used to leverage further capital for investment and growth. To free it up, clear titling

would be required along with a reduction of red tape and corruption, and a brand new

10

CTV.ca News Staff, “Foreign Ministers vow to be ‘partners’ with Haiti,” accessed on January 30, 2010 at

www.http://ottawa.ctv.ca/servlet/an/plocal/CTVNews/20100125/Haiti_conference_100125/2010

11

Government of Haiti, “Vers un Nouveau Paradigme de Cooperation,” April 2009

12

Jacqueline Charles, “Haiti President Rene Preval quietly focuses on ‘managing country,” Miami Herald,

February 2, 2010

13

Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital (New York:Basic Books, 2000).

Page 12 of 15

attitude toward Haiti’s most vibrant form of capitalism – its’ informal economy – and

the poor entrepreneurs who make it work. Doubtless, you have seen post-quake stories

of how Haiti’s grassroots entrepreneurs began rebounding within days.

A key to Haiti’s recovery – and, yes, to its rebalancing – is to get capital into the hands of

grassroots entrepreneurs – be they still in Port-au-Prince or elsewhere in the country.

Formalizing dead capital – which will be a long, tedious and conflictive path, but one

that perhaps can be facilitated now through such steps as the issuance of provisional

land and property titles that subsequently are fully formalized – is but one way of

getting liquid assets into poor people’s hands. Others, more expeditious, include:

More small loans (microcredit) to entrepreneurs, particularly those who

produce something, including farmers. Farmers with capital will not just

produce more food, but will increase employment. Government studies

indicate that a 10% increase in man-hours on farms will create 40,000 new

jobs.14 One strong candidate to improve microcredit throughout Haiti is an

organization called FONKOZE. With more than 33 branches country-wide, it

serves some 175,000 members, mostly among those who make – or made prior

to their engagement with microcredit - $2.00 a day or less. FONKOZE also

facilitates the efficient and lower cost decentralizing of the flow of funds sent

to Haiti from family abroad.

14

Government of Haiti, “Rapport d’évaluation des besoins après dèsastre Cyclones Fay, Gustav, Hanna et

Ike,” November 2008.

(end of part 1 of 2 — go here for part 2 of 2)

UPCOMING THEME and CONTEST: Animals

postmark deadline April 2, 2010For an upcoming issue, we're seeking new essays about the bonds--emotional, ethical, biological, physical, or otherwise--between humans and animals. We're looking for stories that illustrate ways animals (wild and/or domestic) affect, enrich, or otherwise have an impact on our daily lives.

Essays must be vivid and dramatic; they should combine a strong and compelling narrative with a significant element of research or information, and reach for some universal or deeper meaning in personal experiences. We’re looking for well-written prose, rich with detail and a distinctive voice.

Creative Nonfiction editors will award one $1000 prize for Best Essay and one $500 prize for runner-up.

Guidelines: Essays must be: unpublished, 5,000 words or less, postmarked by April 2, 2010, and clearly marked “Animals” on both the essay and the outside of the envelope. There is a $20 reading fee (or send a reading fee of $25 to include a 4-issue CNF subscription); multiple entries are welcome ($20/essay) as are entries from outside the U.S. (though subscription shipping costs do apply). Please send manuscript, accompanied by a cover letter with complete contact information, SASE and payment to:

Creative Nonfiction

Attn: Animals

5501 Walnut Street, Suite 202

Pittsburgh, PA 15232

THE NELLIGAN PRIZE FOR SHORT FICTION2010 SUBMISSION GUIDELINES

Entries must be clearly addressed to:

- $1,500 will be awarded for the best short story, which will be published in the Fall/Winter 2010 issue of Colorado Review.

- This year's final judge is Andrea Barrett; friends and students (current & former) of the judge are not eligible to compete, nor are Colorado State University employees, students, or alumni.

- Entry fee is $15 per story, payable to Colorado Review; there is no limit on the number of entries you may submit. If you prefer to pay the entry fee online (best for entrants outside the US), click below. Please print a copy of your PayPal receipt and include it with your entry. Please do not submit before January 12, 2010.

Special offer to Nelligan Prize entrants: subscribe to Colorado Review for only $10 (one year, 3 issues).- Stories must be previously unpublished.

- There are no theme restrictions, but stories must be under 50 pages.

- All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced.

- No submissions via e-mail.

- Include two cover sheets: on the first, print your name, address, telephone number, and the story title; on the second, print only the story title. Your name should not appear anywhere else on the manuscript.

- Provide SASE for contest results.

- Manuscripts will not be returned.

- Contest opens January 12, 2010.

- Deadline is the postmark of March 12, 2010.

- Winner will be announced in July 2010.

- All submissions will be considered for publication.

Nelligan Prize - Colorado Review

9105 Campus Delivery

Department of English

Colorado State University

Fort Collins, CO 80523-9105

The 2010 Tusculum Review Poetry Prize offers a $1,000 (U. S.) purse and publication. There is a $15 (U. S.) entry fee, which includes one copy of the vol. 6/2010 edition of the The Tusculum Review and consideration for publication. We consider all works submitted for publication, but only works with entry fees are considered for the contest.

Submissions must be postmarked by March 15, 2010 for consideration.

Each submission is restricted to 1-5 poems, no more than 10 PAGES per submission. All entries must be typed. Poets may submit more than one submission, but each submission must include the required $15 (U. S.) entry fee.

Previously published poems, including web publications, are not allowed. Simultaneous submissions are acceptable if our editors are notified immediately that the work has been accepted elsewhere.

Please send a cover letter with your name, postal address, phone number, e-mail address, and the title(s) of your work. Please do NOT include your name on your actual submission. For those entering more than one submission, you may designate a gift copy of The Tusculum Review vol. 6/2010. Please provide the name(s) and address(es) for where you want the journal(s) mailed.

Manuscripts will be numbered and all names on the manuscripts will be removed before they are presented to the judges. In the event that judges do not deem any submissions worthy of the prize, The Tusculum Review reserves the right to extend the call for manuscripts or to cancel the award.

The final judge this year will be Allison Joseph. Family, friends, and previous students of the judge, or those with a reciprocal professional relationship with the judge, will be disqualified from the contest. Submissions will be screened by the staff of The Tusculum Review, and finalists will be forwarded for judging.

All contestants will receive a letter announcing the winner and finalists with their copy of The Tusculum Review vol. 6/2010. The winner and finalists will be listed on The Tusculum Review website in April 2010. The new issue will be mailed in May 2010.

Manuscripts will not be returned.

Mark all envelopes, “Poetry Contest.”

Send all work to:

The Tusculum Review

60 Shiloh Road

P.O. Box 5113

Greeneville, Tennessee 37743.

We accept checks and money orders payable to The Tusculum Review.

For more information, contact the editors at review@tusculum.edu or 423.636.7300 ext. 5285.

Contests

Fourth Annual Schlafly Beer Micro-Brew Micro-Fiction Contest

Submit your best micro-fiction and compete to win a $1,500 First Prize plus one case of micro-brewed Schlafly Beer!

Rules:

500 words maximum per story, up to three stories per entry.

$20 entry fee also buys one year subscription to River Styx.

Include name and address on cover letter only.

Entrants notified by S.A.S.E.

Winners published in our April issue.

River Styx editors will select winners.

All stories considered for publication.

Send stories and S.A.S.E. by December 31st to:River Styx's Schlafly Beer Micro-fiction Contest

3547 Olive Street, Suite 107

St. Louis, MO 63103River Styx

2010 International Poetry Contest$1500 First Prize

Send up to three poems, not more than 14 pages.

All entrants will be notified by S.A.S.E.

$20 reading fee includes a one-year subscription (3 issues).

Include name and address on cover letter only.2010 judge: Maxine Kumin.

Winner published in Fall issue.

All poems will be considered for publication.Postmark poems by May 31st to:

River Styx Poetry Contest

3527 Olive Street, Suite 107

St. Louis, MO 63103-1014WINNERS OF THE 2009

River Styx International Poetry ContestThank you for submitting your work to the 2009 River Styx International Poetry Contest. Here are the 2009 results:

- 1st Place Michael Hudson, "Drunk in Bed with an Old Book about the History of Human Flight"

- 2nd Place Michael J. Grabell, "Before Committing"

- 3rd PlaceJ. Stephen Rhodes, "My Cathedral"

- Honorable Mentions

Matthew Fluharty, "The First"

Don Colburn, "In the Unlikely Event of a Water Landing"

Leonard Kress, "Harmonium"

Stephen Gibson, "Duomo and Baptistery, Florence"

Elizabeth Kirschner, "The Collector’s Favorite Doll"

Travis Mossotti, "Inside the Skull"River Styx Founder's Award

Poetry Contest for St. Louis Area High School Students

- 1st Place McCarthy Grewe, Priory

- Honorable Mentions:

Virginia Morrell, Parkway Central

Ben Constantino, Priory

Kyle Hill, PrioryWINNERS OF THE 2009

River Styx Schlafly Micro-Fiction Micro-Brew ContestThank you for submitting your work to the 2009 River Styx Schlafly Micro-Fiction Micro-Brew Contest. We received over 500 submissions this year. Of those, our editorial panel selected twenty finalists, and then selected the winners. We thought the overall quality of manuscripts was exceptionally high. Here are the 2009 results:

- 1st Place Amina Gautier, "Minnow"

- 2nd Place Rose Bunch, "Season"

- 3rd Place Gerry Canavan, "When We're Gone"

- Honorable Mentions

Avni Vyas, "Cartography"

Lisa Nikolidakis, "Misplaced"

Fred Venturini, "Punches"

Gary Leising, "Enter Fortinbras"

True Stories That Prove God's Word & Miracles Still Work Today"

WELLINGTON, OH ( December 14, 2009) Limbs nearly severed, kidnapping, abduction, gender identity confusion, gunshot wounds, terminal illness and abuse were survived, triumphed over and transformed into "teachable moments" by the seven women whose stories are chronicled in this book. Their histories and personalities are as different and unique as their testimonies. However, there is a common thread that binds them -- they all are ordinary women who serve an extraordinary God.

Ciaj (pronounced See-a h-juh), an essayist, poet and fiction writer has lent her talent to non-fiction by writing and editing "Faith..." and states: "These testimonies and witnessed miracles are more compelling than any work of fiction at a time when we need miracles more than ever." She further notes that the truth about the power of God to heal, deliver, protect and restore produced memoirs that are more captivating and relatable than tales that are sometimes fabricated for the express purpose of trying to make Oprah's Book Club or the NYT Bestseller List.

CiajDiann Harris, a paralegal and former state law enforcement officer and mental health tech, also worked in journalism as a staff writer for a newspaper. She received her bachelor's degree in business administration from Tiffin University and attended Cleveland-Marshall College of Law before being called into ministry. In 2005, her work was published in "Surviving in the Hour of Darkness: The Health and Wellness of Women of Colour and Indigenous Women" edited by G. Sophie Harding and published by University of Calgary Press and I Woke Up and Put my Crown On: The Project of 76 Voices edited by Rochell D. Hart. She is working on her next book: "Mommyisms & Daddylore: Common Sense & Straight Talk About Relationships" as well as the stage adaptation of "When I Stepped Out on Faith..."

Ciaj said: "Renowned New York literary agent, Marie Brown once asked me where I was from in Ohio. When I told her Lorain, she said, 'Oh, Toni Morrison.' My reply was, 'Yes, there's somethin' in the water.' Lorain also is the hometown of Michael Dirda, Washington Post Book critic and former senior editor of the Washington Post Book World. Ciaj continues: "Reading Morrison's "The Bluest Eye" and Dirda's "An Open Book..." and seeing the stark similarities to my early years written on the pages of novels by Nobel a nd Pulitzer Prize winning authors -- infused my possibilities with t he power of probability. But it was much more than Lake Erie that we had in common. We shared a culture and values that stood the test of time -- for a long, long time. I grew up in the same neighborhood as Toni Morrison a couple decades after she did but we also had many of the same teachers -- teachers, who challenged our minds, encouraged our achievements and were instrumental in shaping our futures."

Letter to Haiti

Haiti, I weep for you. I hide my tears because I’m on a flight from Kelowna, British Columbia, to Toronto, and who knows, with all the heightened security I fear they may think something’s amiss. That I’m weeping as a prelude to joining my ancestors. So paranoid have we become. But I weep for you, Haiti, for your people, for the shit — the unmitigated shit — that life seems to throw your way. Again and again. And, to adapt the words of one of your warrior daughters, Maya Angelou, “still you rise,” to greet another green, tropic day that holds hope ransom, as you tear your people limb by painful limb from a hell that eschews fire and opts instead for the hardface, stoneface indifference of concrete that, Medusa like, seems to have frozen all of your magnificent history into slabs of cement. Now fragmented they litter your landscape as if some giant, angry at us mortals, had decided to stamp on your already precarious country. There was a time when our Caribbean houses kept faith with wood, whether one-room homes — some call them chattel houses — or larger, more graceful estate houses. Time was when the thatched Ajoupa bequeathed us by Taino, Arawak and Caribwould have swayed to the groans of the earth as she eased her suffering, opening herself along her wounded fault lines to the ever blue skies, the constant love of the sun, to release all her pent up grief for us, birthing we don’t yet know what. Time was when hands steeped in skills of building homes brought from a homeland a slap, kick and a howl away, across a roiling ocean, would have gently patted mud over wattle, weaving branches to create cool interiors, shaping shelters from the earth that would not, could not, betray the safety in home to crush, obliterate, to fall down around your ears. Like the third little pig in the nursery rhyme, Haiti, you built your home of brick — it was supposed to protect you.

Each and every time I hear or read the words that describe you as being a poor nation, the poorest of the poorest — I weep. Poor you most certainly are in all things material, but your riches are immeasurable, woven through your history, your culture and your people. Yours was the first and only successful slave revolt in the Western world and resulted in the second independent nation after the United States in the so-called New World. In taking the name the Taino had given the “Land of Mountains,” Ayiti, you returned the country to its First Nations roots. How many know that the USA embargoed you for sixty years because you fired a shot across the bow of history by liberating your people under the brilliant leadership of Toussaint L’Overture? How many know that you became a pariah in the world for taking a moral stance in favour of justice and freedom and against racial exploitation and oppression? Then, you were at another epicentre, along one of the many fault lines of history, the reverberations of which seismic, political shift would be felt around the world. Indeed, are still being felt, I would argue. No one rushed to help you then, Haiti. Instead, what we had were France, Spain, Holland, Britain and the United States (albeit secretly) — shall we call them the coalition of the ready, willing and able, or simply the usual suspects? — preparing to invade you to re-impose the yoke of slavery. How many know that your liberation determined the eventual downfall of Napoleon? So decimated were Napoleon’s troops under his brother-in-law, General Leclerc, by fighting in Haiti and by yellow fever, they could not provide the necessary support for Napoleon’s subsequent campaigns in Europe — against Spain, Russia and Prussia to be exact. In November 1803, France, under Napoleon, capitulated. In January 1804, General Jean Jacques Dessalines declared you an independent nation. How many know that France, that bastion of revolution and freedom, by the Ordinance of 1825 exacted the sum of 150 million francs as compensation from you for loss of “property” — read: formerly enslaved Africans? How many know or even care to know that you did, indeed, pay your extortioner through a series of loans that bankrupted you? The equivalent of that sum is $21 billion in today’s money. And how many know that the USA invaded you in 1915 and occupied you until 1934? Hearing that the US military now controls the airport makes me shudder. Makes me want to hold my head and bawl.

Only South Africa among a continent of African nations has dared to do this — most flee this reminder of who they are. No other Caribbean island nation has followed suit. Most of all, Haiti, you are rich in your people — their dignity, their love of homeland and willingness to struggle for freedom. What more fitting example of this is the recognition of the language of the people,Haitian Creole, as an official language? With the exception of the three formerly Dutch colonies, Aruba, Bonaire and Curacao, no other Caribbean island nation has officially recognised the language of the people, for the people and by the people — the vernacular, the demotic — Kamau Brathwaite’s nation language — as worthy of recognition. Ah, but most of all, Haiti, I weep for the “dream deferred” that Langston Hughes so eloquently wrote about. What has happened to the many deferred dreams of your people? Where have they gone? How many know that at the start of your fledgling nation in 1804, democratic principles were central to your constitution? First, you abolished slavery, then moved to enshrine one of the most frighteningly revolutionary and emancipatory ideals in your constitution — racial equality — even granting citizenship to Polish soldiers who had fought alongside Haitians against the French. In 1804 that would have been the equivalent of an earthquake measuring at least 8 on a Richter scale of oppression. You were at the heart of the awakening of modernity — albeit a deferred modernity. More than anything else, you presented, in the words of the Canadian poet, Jordan Scott, a profound “threat to cohesion.” The cohesion of imperial power founded on brute racism.

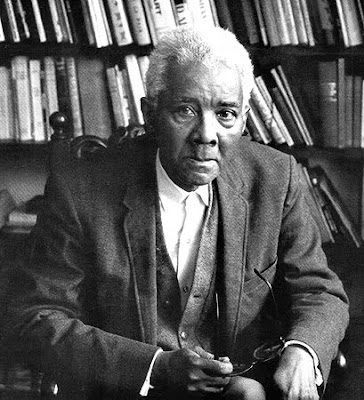

I weep for you, Haiti, and for I ‘n’ I, because when I bear virtual witness to your despair and your suffering, when I see the mountains of rubble and concrete, the broken roads, the tangle of electrical wires, and hear the voices droning on and on about the lack of infrastructure, I think of my own internal infrastructure — spiritual, psychic, intellectual and political — and realize that your history has played no small part in its structure and design. I recognize you writ large through CLR James’ The Black Jacobins that I first read as a young Caribbean woman trying to find her place in a world and a history that had hardly begun to be told. Your history, your struggle, your survival, epitomised through the successful Haitian revolution, as told by James, became a part of my own struggle to understand my place and the place of my people in this world — on all those tiny pieces of coral or volcanic rock scattered in the ever blue Caribbean Sea. Through The Black Jacobins we, each and every one of us who read that work, grew in stature internally as Caribbean people, children of the volcano all, to quote the brilliant Martniquan poet and founder of negritude, Aimé Césaire; became larger psychically, and more intellectually secure in our role as agents of change. In our own history.

Toussaint’s name lived in our minds and on our tongues as young Caribbean thinkers, the first generation to have access to widespread, tertiary level education. The coloniser’s language may separate us, but only superficially, for CLR James who brought your struggle home to us and helped us to understand ourselves through the lens of history, is as much a son of yours as Boukman, Toussaint, Dessalines or Christophe. Indeed, your daughters and sons know no borders. For African-American poet and writer, Ntozake Shange, “TOUSSAINT waz a blkman...who refused to be a slave...TOUSSAINT L’OUVERTURE waz the beginnin uv reality” for her. A dazzling, polyvocal, linguistically innovative tour de force, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, although located in the US, grounded itself in a historical reality that began with Toussaint.Samuel Huntington (him of The Clash of Civilizations) had the impertinence to describe you as “the neighbour nobody wants” and as being “truly a kinless country,” and in so doing reveals how little ignorance respects knowledge. Little does he know how far, how wide and how deep your kin are spread.I gaze at a map of Port au Prince in a newspaper identifying high profile sites of destruction: it is as if someone decided you had to start again, and wiped the slate clean: the Ministry of Justice — gone; the Presidential Palace — gone; administrative offices — gone; the penetentiary — gone; the hospitals — gone; churches — gone; the cathedral — gone. Hundreds of thousands of people — gone. All gone — just like that. In the clichéd wink of an eye — God’s perhaps? Or the devil’s snap of fingers. Leaving nothing but bright mornings filled with mourning, despair, grief and pictures of little Black girls with locks made blonde by concrete dust, who look out at the world through glasses, bearing the weight of history and a building on their little legs. Oh God, oh God, why hast thou forsaken us? This is the language — the language of the Bible — that bursts forth, as if the apocalyptic nature of the disaster itself demands a language of Biblical proportions. Because flesh hurts, and love and grief know no bounds when your loves are entombed before your very eyes, sometimes leaving no one to mourn, no one to cry out, Why? Why? Why? And, worse than that, no one to answer why.

There was a time when for five hundred years the world, with very few exceptions, was indifferent to the suffering of African peoples. They entered the maw of a history drenched in brutality, as history most often is, through the doorway of the slave ship and, by way of what we so euphemistically call the Middle Passage, were washed up on these Caribbean islands like so much flotsam and jetsam the Atlantic was rejecting. To enter the machine of the plantation. Who shed a tear, beyond those left in Africa, for those entombed in slave ships? Who shed a tear for those whose bones litter the sands below the Atlantic? Who shed a tear for the living death of the slave plantation? As recently as 2005 we were witness to the indifference that greets the suffering of Black folk in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. By their own government. Under George Bush.

Always an agricultural nation, you once grew your own rice, then cheap subsidised rice from the USA flooded the nation and your self-sufficiency in rice was lost, so that during the 2008 food crisis (which continues), when the price and availability of staple foods like rice shot up, you were particularly vulnerable. According to Peter Hallward, writing in the Guardianin January 2010, during its occupation of your territory the US “violently and deliberately” resisted “every serious political attempt to allow Haiti’s people to move (in the words of Jean Bertrand Aristide) ‘from absolute misery to a dignified poverty’.” And make no mistake about it, had it not been for the support of the Soviet Union, Cuba would have been beggared in the same way by the embargo the US imposed after the Cuban revolution.The world has found you now, Haiti, but where was it when France was extorting blood money from you, ably assisted by the US who arranged loans to help you repay France — loans designed to break you economically? Where was it? The world. It is against the principles of international law that a victorious country should pay a country it defeated for its freedom, yet the nations of the world have been silent on this travesty. One of the claims Aristide made during his tenure was for reparations from France for these immoral and illegal payments. Where was the support for these claims from the world? Where was the world when the US occupied you? Busily fighting to save Europe from the calamity that Hitler portended, shoring up the principles of freedom in resounding Churchillian phrases, where the fuck was the world? As the flag bearer of democracy crushed a small but proud island nation, and today, even today, as hungry, frantic Haitians take to the seas in desperation, seeking refuge anywhere, even in water as their ancestors did, even today, the US Coast Guard turns them back. Where was the world when the US rounded up your boat people to return them, unlike the Cubans, to their home country? Where was the world, Haiti? And will it still love you when you occupy your rightful place? For occupy it you will. Our very survival — the survival of every one of your children depends on it.Today I saw a little boy birthed from a concrete womb a mere letter away from a living tomb, his rescuers pulling him from the rubble as if he were being born again — for the second time in his so very short life. They snatch his frail-limbed body, whitened with concrete dust and, cradling him in their arms, run with him. And I think, so it was when you defied the long, the very long historical odds against you, and out of the living tomb of slavery created a womb to birth yourself. Blood and all.

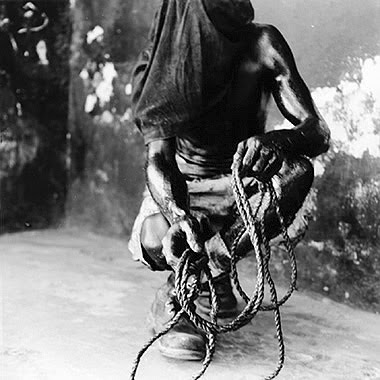

Today, they say it’s your culture that prevents you from moving forward — that vaudon creates a fatalism that is out of step with the ideals of progress endemic to the West. And I wonder why that fatalism didn’t keep you wedded to a slave culture.But what good is history when your child done dead and gone? Or your mother bury under concrete, or your daddy, grandmère or grandpère nowhere? You cyant eat revolution, you cyant drink freedom. And, as the saying goes, a hungry man is an angry man. It is not surprising, but still I am surprised at the rapidity with which the trope of violence has raised its head: not even a week has gone by before the Toronto Star has a front page picture of a naked, bound man being beaten. The following day the headline screams about violence marring the relief efforts. The following day still a front page picture appears of a knife-wielding man appearing to attack someone for food. It’s the stereotype with which the media and those that “run tings” have clothed us. Beggars or criminals. Or sometimes both, as the Star makes out. Even as they purport to help, they construct prisons of stereotypes for us. How quickly the world has forgotten the unspeakable violence that slavery meted out on African peoples for at least five hundred years. Indeed, Leclerc wrote of his intent to “wage a war of extermination” to reintroduce slavery in your barely formed nation. You have never been forgiven for successfully resisting his violent attempt to subjugate you. To decontextualize the violence in Haiti, as the Star has done in those three issues, under the guise of needing to show Canadians the “true horror of this disaster” appears to be nothing more than a crass and racially exploitative attempt to sell more newspapers.

I will not romanticize your history; cannot pretend that the dreams and hopes of that seminal revolution have not been curdled over the years. Toussaint may have abolished slavery, reorganised the administrative and justice systems, built roads, schools and bridges, but Papa Doc and theTon Ton Macoutes did exist. So did his son, Baby Doc. Class and race divisions in Haiti are alive and pernicious, but when I hear Bill Clinton talk about the need for Haiti to shake off her history, I wonder what history he is referring to. The history of Toussaint, or the history of Papa Doc, or both?And when I hear of George Bush urging people to send money, not clothing, I laugh. I remember him urging his populace after 9/11 to go out and shop. And look where that got them. And I think of Obama appointing these two men and I laugh again. Because if I didn’t, I would sure be crying.Fired in history’s unrelenting sun, we Caribbean peoples who hunger after justice, who long for peace, who have lived cheek by jowl with, and sometimes in the belly of, the beast, have always punched above our weight through history — I need only mention Castro, Fanon, James, Césaire, Wynter, Brathwaite, Walcott, Lamming and Claudia Jones, to name but a few; we grasp the import of our role in history, and no small credit for that must go to Toussaint L’Overture and all the history that swirls around him. We understand, being the subjected to them for far too long, the effects of great power machinations; they continue to reverberate in our tiny island nations as well as in the psyches of the people. The coloniser may have withdrawn but he has left his mark.

The African-American dancer and anthropologist Katherine Dunham, another of your daughters, had a long and deep relationship with you, even becoming an initiate of the vaudon religion. In Island Possessed she describes her relationship with the Haitian people and her involvement in the culture; she talks of buying the plantation that once belonged to selfsame General Leclerc and of her need to cleanse it of the remnants of the sordid, brutal history of empire she could feel on the property. With the help of her Haitian godmother she does, indeed, shift the negative energies she first felt there. The sheer enormity — the apocalyptic nature of this tragedy — makes me wonder if there is something larger at work here, with you, Haiti, once again being at the epicentre of some violently physical, yet spiritual, temblor, echoing that earlier one two centuries ago. Is this simply, and not so simply, the human longing and search for meaning on my part? Is it this urge to find meaning in our lives and experiences, particularly catastrophic ones, that drives the likes of Pat Robertson, a so-called man of God, to describe your plight as punishment for making a pact with the devil — a comment so egregiously lacking in compassion as to take the breath away? If nothing else he has made the choice very clear: if fighting to free one’s self puts you on the side of the devil and being on the side of God puts you in a place where, like him, you cannot express a scintilla of compassion for another’s suffering, then my sympathy will be with the devil. Always. It is early days yet, I tell myself, to attempt to find meaning in this violent catastrophe whose scale and scope often appears to exceed language, even as my mind feverishly tries to find meaning. Trying to link your history as an unblinking beacon for the Black struggle for civil and human rights, for the quest for freedom, for justice and for dignity on the part of African peoples, to this present maelstrom, as if we didn’t have maelstroms aplenty already. Indeed, in this time of acute suffering it feels premature, if not sacrilegious, to rush to meaning. So, I resist that, for the present, understanding and accepting that any meaning to be found, lies, perhaps, in the sheer absence of meaning — shit just simply happens, it seems. But I do recall another of your English speaking sons, the novelistGeorge Lamming, who feels the heft of your history, making reference years ago in The Pleasures of Exile to the Haitian Ceremony of the Souls, which brings together the people and their ancestors — the living and the dead. What links them is a shared interest in their future — in the one case continued life, in the other eternity. There is a sense in which James’ The Black Jacobins drew us all in the Caribbean into an extended performance of the Ceremony of the Souls: we, the living descendants of the enslaved, being in active relationship with the memory of Toussaint and his supporters. Today your dead lie all around you, and despite the lack of dignity of their final resting place, you honour them in your deep dignity, notwithstanding the pictures of theStar, and in your resilience.And once again, through your undeserved suffering, but then suffering of the innocent is never deserved, you become a symbol for me, for us all — your children in spirit — a symbol of the will to survive in the face of apparently insuperable odds. It is what makes us human and simultaneously calls on our humanity. In that respect, we are all Haitian.Many years ago, David Rudder, one of Trinidad and Tobago’s most beloved performers, sang a soca ballad titled “Haiti,” its refrain a simple lament: “Haiti, I’m sorry.” It begins: “Toussaint was a mighty man/ and to make matters worse he was black/ back back in the time when a blackman’s place was in the back.” The ballad recounts your history and how badly served you have been by history; how we, and in particular Caribbean peoples, have misunderstood you, turning our faces from you. It pains me that more of our island nations have not, over the years, offered refuge to your people — how many heads of state from the Anglophone Caribbean attended the two hundredth anniversary of your revolution in 2004? One, I believe. Haiti, I, too, am sorry, but I do not weep for you, for that would be to pity you; I weep with you, Haiti, with compassion, wanting to share your suffering, which lies at the root of the word compassion. Today I am Haitian and forever in your grief and your undeniable survival, because survive you will. You must. For all our sakes. All I have are my broken words. And my tears. And my more tears. My so many more tears. With you, Haiti.Viva Toussaint! M. NourbeSe Philip is a Canadian poet, novelist, playwright, essayist and short story writer. One of this blogger's favourite writers, find further information on her by visiting her Web site: Nourbese.com. Leah Gordon is a Haitian-based, UK-born, photographer and documentary filmmaker who greatly assisted with Haiti's 2009 Ghetto Biennale. View a wonderful excerpt of her film Atis-Rezistans: The Sculptors of Grand Rue. And please visit her Web site: LeahGordon.co.uk. "Letter to Haiti" is copyright of M. NourbeSe Philip and is republished with her permission.

LifeScapes: Where I Cast My Eyes From Where I Am

Monday, February 8th through Thursday, March 4th, 2010

Opening Reception Saturday 2/13/10, 4-5:30pm in the Library Community Room.

Atlanta Fulton Public Library

Buckhead (Ida Williams) Branch

269 Buckhead Ave.

(404) 814-3500Hours:

Monday and Wednesday 10 am to 8 pm

Tuesday and Thursday 10 am to 6 pm

Friday and Saturday 11 am to 5 pm

Sunday - closed------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Monday, March 1st through Friday, March 26th, 2010

First Thursday Art Walk Opening Reception, is March 4, from 6:00pm - 8:00 pm

Opening reception Sunday, March 14, 3pm - 5pm

Atlanta-Fulton Public Library

Hours:

1 Margret Mitchell Square NW

Central Branch ~ Lower Level

Atlanta, GA 30303

404.730. 1700

Monday -Thursday 9am - 9pm

Friday - Saturday 9am - 6pm

Sunday 2pm - 6pm