Spring 2011, Vol. 43, No. 1

John Brown:

America's First Terrorist?

By Paul Finkelman

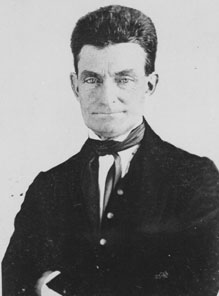

For Southerners, Brown was the embodiment of all their fears—a white man willing to die to end slavery. For many Northerners, he was a prophet of righteousness. (111-BA-1101)

As we celebrate the beginning of the sesquicentennial of the American Civil War, it is worthwhile to remember, and contemplate, the most important figure in the struggle against slavery immediately before the war: John Brown.

When Brown was hanged in 1859 for his raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, many saw him as the harbinger of the future. For Southerners, he was the embodiment of all their fears—a white man willing to die to end slavery—and the most potent symbol yet of aggressive Northern antislavery sentiment. For many Northerners, he was a prophet of righteousness, bringing down a terrible swift sword against the immorality of slavery and the haughtiness of the Southern master class.

In 2000, the United States marked the bicentennial of Brown's birth. At that time, domestic terrorism was a growing problem. Bombings, ambushes, and assassinations had been directed at women's clinics and physicians in a number of places; a bomb planted in Atlanta's Centennial Olympic Park during the 1996 summer Olympics had killed one person and wounded more than a hundred people; in 1995 a pair of right-wing extremists had planted a bomb at the Alfred A. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people and injuring more than 680 others.

During that bicentennial year, a number of historians and others talked about whether John Brown was America's first terrorist. Was he a model for the cowards who planted bombs at clinics, in public parks, or in buildings? Significantly, at least one modern terrorist, Paul Hill, compared himself to John Brown after he was arrested for murdering two people who worked at a women's clinic in Florida.

A year after Brown's bicentennial, the United States was faced with multiple terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. The meaning of terrorism had changed. It was no longer the result of random attacks by an individual or two. Now it was tied to a worldwide conspiracy, coordinated overseas and meticulously planned. The American response was a "war on terror." In an age of rising incidents of terrorism, numerous scholars, and more important, much of the general public, have again asked if John Brown was America's "first terrorist."

Some Definitions of Terrorism

There are no complete or certain definitions of terrorism. Terrorists seek to "terrify" people and strike fear in the minds of those at whom their terror is directed. This, however, is not a complete definition. After all, few would consider soldiers in warfare terrorists, yet surely they try to make their enemy "fearful" of them. Starting with World War II, large-scale bombing has been a fact of modern warfare, but bombing of military targets is surely not an act of terrorism, even though the civilian population may be harmed or terrorized.

This aspect of warfare is hardly new. Siege warfare of the ancient and medieval world surely terrorized those inside castles or towns. Similarly, the long sieges of the Civil War, as well as decisions by both sides to strike at civilian targets that aided the war effort, surely terrorized populations. The trench warfare and artillery duels of World War I terrorized millions of civilians, but this was not essentially terrorism.

So, what beyond scaring or frightening people constitutes terrorism? How do we define the "terrorist?"

For terrorists, the "terror" itself, the act of violence, is the goal rather than simply the means to an end. Terrorists may hope for political change, but what they often want is to simply strike back at and harm those they oppose. The act of terror becomes the goal, with no expectation that anything else will follow.

This makes terrorism different from other kinds of illegal activity or violence. A kidnapper wants a ransom; a hostage taker usually has "demands" that should be met; a robber simply wants money or goods and might be willing to kill for them. But the terrorist often has no demands and no goals other than to terrorize. Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols made no demands; they wanted nothing other than to kill and destroy. Those who attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon only wanted to kill, destroy, and terrorize. They made no demands, asked for nothing, and by their own design would not have even been alive to negotiate for whatever they might have wanted.

Another hallmark of terrorists is indiscriminate killing; it helps spread terror. Terrorists generally do not care who they kill—adults, children, old people, women, men—although sometimes assassinations are an exception to this.

Terrorists are not concerned about collateral damage. Planting a bomb or shooting indiscriminately is a key indicator of terrorism. It does not even matter if some of those who die are sympathetic to the terrorists or of their own ethnic group. A number of American Muslims died in the attack on the World Trade Center because that is where they worked, but these collateral deaths were of no consequence to those who planned the attack. For terrorists, indiscriminate killing helps spread terror. Similarly, for terrorist killers there is no reason to spare lives or minimize death—every life is a legitimate target.

Terrorists usually attack nonmilitary targets and those who are unable to defend themselves. Often their victims are what might be called noncombatants in whatever ongoing struggle there is. One common aspect of terrorists is that they avoid direct contact and confrontation with those who are armed, especially the military. Tied to this, most terrorists plan their actions to have the greatest impact and to kill the most people.

Terrorists also act in secret and try to avoid anyone knowing who they are. They often wear masks and in other ways try to hide their identity. The classic American terrorist is the sheeted Klansman, with his face covered, killing, beating, mutilating, burning, and raping, to terrorize those who supported racial equality and black suffrage. Because they are violent and seek to kill, maim, or destroy property, terrorists naturally must be secretive. After their acts, however, they are likely to openly (but anonymously) brag about their crimes.

Terrorism also has a political context. This is particularly important to see when we try to make the distinction between terrorism and revolution. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson set out a series of principles that justified violent overthrow of the government. One was a "long train of abuses."

Even more important for Jefferson and his colleagues was the lack of access to the political process to change things peacefully. From the American perspective, in 1776, there was not a political solution to the crisis because Americans had no voice in the British government. In addition, the American Revolution was a response to attacks initiated by the British.

Thus, where there are no political avenues for change, violence—such as the American troops firing at the British—becomes revolution. But where the political processes are open, violence becomes terrorism. This was even true for the 9-11 terrorists. Nothing prevented them from politically organizing, demonstrating, and educating the American public about the changes they wanted. Their choice was to short-circuit the political options in favor of violence and terrorism.

With these general understandings, let us turn to John Brown, first to understand what he did, and second to see if it fits in the context of terrorism.

What Brown Did

Brown is connected to terrorism for two events in his life: the Pottawatomie raid in the Kansas Territory in 1856 and his raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1859. Both involved violence and killing. Both have led some people to claim Brown was a terrorist.

On the night of May 24, 1856, Brown led a raiding party of four of his sons, his son-in-law, and two other men to Pottawatomie Creek. For the most part, this raid was unplanned and almost spontaneous. Brown acted in retaliation for a raid on the free state settlement at Lawrence, the killings of free state settlers in Kansas, and persistent threats by the proslavery settlers along Pottawatomie Creek. Brown and his men entered three cabins, interrogated a number of men, and eventually killed five of them, all with swords and knives. Some were killed quickly, while others, who resisted, were cut in many places. Brown and his men then departed.

Significantly, although Brown and his men killed five proslavery settlers, they did not kill all the Southern settlers they encountered. They spared the life of the wife and teenage son of one of the men they killed, even though these people could have identified the raiders. At another cabin, they interrogated two men and let them go, convinced they had not threatened free state settlers or been involved in violent actions against the free state settlers. At a third house they also spared the wife of one man, even while they killed him.

Three and a half years later, on the evening of October 16, 1859, John Brown and 18 "soldiers" seized the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown's plans were fantastic—some would say insane. He would use the arms in the arsenal—as well as old-fashioned pikes he had had specially manufactured—to begin a guerrilla war against slavery. The core of his army would be the mostly white band of raiders who seized the arsenal. But soon, he hoped—he believed—he just knew—that hundreds or even thousands of slaves would join him in the fight against the "peculiar institution." He predicted that once word of his raid got out, slaves from throughout the region would appear at his side, as bees "swarm to the hive."

During his raid, Brown and his men had captured a number of slave owners in the area, including Lewis Washington, the great-grand-nephew of President George Washington. Brown did not kill any of these captured men, and he went out of his way to protect them and make sure they were not harmed.

While in Harpers Ferry, the raiders killed a railroad baggage handler, who ironically was a free black, when he refused their orders to halt. In a firefight they killed a few townsmen, including the mayor. At one point Brown stopped a passenger train, held it for a while, and then released it. The train continued on to Washington, D.C., where the crew dutifully reported to officials that Brown had seized Harpers Ferry. The next day, October 18, U.S. marines, under the command of Army Brevet Col. Robert E. Lee, captured Brown in the engine house on the armory grounds. By this time, most of the raiders were either dead or wounded.

Brown's trial in Charlestown, Virginia, began in October 1859. He was charged with and convicted of treason, murder, and conspiring with slaves to revolt. Severely wounded during his capture, Brown had to be carried into court and lay on a stretcher. (Harpers Ferry National Park)

Ten days later, Brown's trial began in Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia). He was charged with treason, murder, and conspiring with slaves to rebel. He was convicted on November 2 and sentenced to death. Before his sentencing, Brown told the court that his actions against slavery were consistent with God's commandments.

"I believe," he said in a speech that electrified many Northerners who later read it, "that to have interfered as I have done in behalf of His despised poor, is no wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I say 'let it be done.'"

In the month between his sentencing on November 2 and his execution on December 2, Brown wrote brilliant letters that helped to create, in the minds of many Northerners, his image as a Christ-like martyr who gave his life so that the slaves might be free. Indeed, Frederick Douglass would later say that he lived for the slave, but John Brown was willing to "die for the slave." Brown welcomed his end, declaring: "I am worth inconceivably more to hang than for any other purpose."

For abolitionists and antislavery activists, black and white, Brown emerged as a hero, a martyr, and ultimately, a harbinger of the end of slavery. Most Northern whites, especially those not committed to abolition, were aghast at the violence of his action. Yet there was also widespread support for him in the region. Northerners variously came to see Brown as an antislavery saint, a brave but foolish extremist, a lunatic, and a threat to the Union.

The future Republican governor of Massachusetts, John A. Andrew, summed up the feelings of many Northerners when he refused to endorse Brown's tactics or the wisdom of the raid, but declared that "John Brown himself is right." But most Republican politicians worried that they would be tarred by his extremism and lose the next election. Democrats and what remained of the Whigs (who would become Constitutional Unionists), by contrast, feared that Brown's raid would polarize the nation, put the Republicans in power, and chase the South out of the Union.

For white Southerners, Brown was the worst possible nightmare: a fearless, committed abolitionist, armed, accompanied by blacks, and willing to die to end slavery. Indeed, in the minds of Southerners, Brown was the greatest threat to slavery the South had ever witnessed. Most Southerners had at least a vague fear of slave rebellions. But Southerners had convinced themselves that most slaves were content with their status and that, in any event, blacks were incapable of anything worse than sporadic violence. Brown, however, raised the ominous possibility of armed black slaves, led by whites, who together would destroy Southern white society.

Who was this lunatic, this mad man, this abolitionist hero, this saint, this martyr to freedom? Was he America's first terrorist?

Who Was John Brown?

In many ways Brown was a typical 19th-century American. He was born in Torrington, Connecticut, into a family of deeply religious Congregationalists who were Puritan in their heritage and overtly antislavery in their views. When he was five, the family moved to what was then the "West." They migrated to Hudson, Ohio, which was in the Western Reserve between Akron and Cleveland. The region was full of New Englanders, especially from Connecticut.

Brown grew up in an atmosphere in which everyone despised slavery. Both Brown and his father were early supporters of the new abolitionism that emerged in the 1830s. Brown's father, a prominent businessman with a large tannery, was involved in trying to make Western Reserve College into an antislavery stronghold. When that failed, the elder Brown supported the creation of Oberlin College as a racially integrated coeducational institution of higher learning with an antislavery bent.

Despite his father's association with colleges, Brown had little formal education. Early in his life he considered becoming a clergyman, and he returned to Connecticut to attend a preparatory school as a prelude to going to a seminary. But that possibility ended when he flunked out of the school. By age 20 he was married and a foreman in his father's tannery. His bride, Dianthe Lusk, gave birth to seven children before she died in 1832. Five of those children lived until adulthood. In 1833 he married Mary Ann Day, an uneducated 16-year-old, half his age. She would have 13 children, but only six would survive to adulthood.

In 1825 Brown moved to western Pennsylvania, where he was a successful tanner and a postmaster (under President John Quincy Adams). Despite his own poor education and struggles with schooling, he helped start a local school. A proper burgher of the community, he became a church leader and joined the Masons. In 1834 his business went bad, and he moved back to Ohio, starting a tannery in Kent. There he speculated in land and won a contract to build a canal from Kent (then called Franklin Mills) to Akron. He formed the Franklin Land Company with 700 acres for building houses.

As we recall Brown's future activities, it is fascinating to also contemplate the image of John Brown as a suburban developer. But the panic of 1837 changed everything. By the end of the year, Brown was bankrupt. For the next five years he dodged creditors before finally declaring bankruptcy in 1842 and losing almost everything he owned.

Up to this point in his life, Brown had done nothing to indicate he was particularly political or unusually antislavery. He was, in fact, a fairly conventional Jacksonian, trying to increase his status and wealth and always looking for the next opportunity: tanner, canal builder, suburban developer, and in the wake of the panic, bankrupt.

By 1844, Brown was back in the business world, raising sheep with a wealthy business partner in Akron. But his inept business skills did him in again, especially an attempt to sell 200,000 pounds of wool in England, which was an exporter of wool. Oddly, while his creditors sued him, no one accused him of dishonesty or lacking integrity. Even people whose finances were almost ruined by his behavior liked him.

John Brown in the 1850s. He had tried to succeed as a tanner, sheep rancher, suburban developer, and canal builder but was undone by failing economic conditions and his inept business skills. (127-N-521396)

In 1854—at age 54—Brown was a failed businessman, an impoverished farmer with a few head of cattle in Ohio and some land in Upstate New York—at North Elba—that he had not yet paid for. That year five of his sons and his son-in-law moved to Kansas. In part they went to improve their economic status and find new, virgin soil for farming. But they also went to spread freedom in the West.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 had organized the new Kansas Territory without banning slavery. Under that law, the settlers themselves would decide the issue of slavery by popular sovereignty. Thus, when the Browns moved to Kansas, they were making a political statement to help ensure that Kansas would be a free state.

During this period, Brown had gradually emerged as an unyielding opponent of slavery. He participated in the underground railroad and in 1851 helped found the League of Gileadites, an organization of whites, free blacks, and runaway slaves dedicated to protecting fugitive slaves from slave catchers.

In the 1840s Brown was in contact with such antislavery leaders as Gerrit Smith and Frederick Douglass. Yet as late as 1855 Brown remained a marginal figure in the antislavery movement and in all other ways historically insignificant. In 1855 Brown joined his sons and son-in-law in Kansas, settling along the Osawatomie River. In December 1855 he helped defend Lawrence, the center of antislavery settlers, from an armed attack by proslavery forces.

On May 21, 1856, though, when Brown was elsewhere, proslavery men sacked and burned the free-soil town, destroying the printing press there, burning buildings, and terrorizing the residents. Three days later, Brown and his band of free-state guerrillas killed five Southern settlers along the Pottawatomie River, decapitating some of them with swords. Later that summer, a proslavery minister, working as a scout for the U.S. Army, murdered Brown's unarmed son Frederick, shooting him in the heart at close range. His body, when discovered, was riddled with bullets.

Throughout the rest of 1856, Brown and his remaining sons fought in Kansas and Missouri. Some of these encounters were pitched battles between Brown's small army and proslavery forces, which were sometimes abetted by the U.S. Army.

By the end of 1856, Brown was one of the most renowned (and either hated or adored) figures in "bleeding Kansas," and in the East he became known as "Osawatomie Brown" or "Old Osawatomie." For some New England abolitionists he was approaching the status of a cult figure. Taciturn, blunt, gruff—and armed—Brown had become a symbol of the emerging holy crusade against slavery. Those in the East knew he fought against slavery, but few were aware of the exact nature of his role in the gory events at Pottawatomie.

Within two weeks after the incident, the play Osawatomie Brown appeared on Broadway. The play accused Brown's enemies of the massacre at Pottawatomie and suggested that the real killers had blamed Brown in order to discredit him. Moreover, ever since the massacre, James Redpath, an English journalist who later wrote Brown's biography, had been assuring readers that Brown was not responsible for the murders. Thus, when Brown went on a fund-raising trip to Massachusetts and Connecticut in 1857, no one saw him as a killer. At the time, he denied any role in the Pottawatomie murders, and his abolitionist supporters in the East gladly accepted his disavowal at face value. Brown's eastern contacts thought their donations to him would go to support the war against slavery in Kansas. Actually, Brown was already planning a raid on Harpers Ferry.

As early as 1854, Brown had been thinking, and talking, about an organized war against slavery in Virginia. His focus, from the beginning, seems to have been on Harpers Ferry, the site of a federal arsenal and armory. By 1857 his plans were beginning to take shape. In March 1857 he hired a Connecticut forgemaster to make a thousand pikes, allegedly for use in Kansas but actually to be given to slaves who he believed would flock to his guerrilla army once he invaded the South.

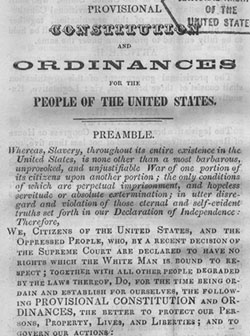

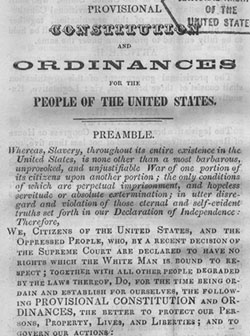

In 1858 Brown wrote a constitution for the revolutionary state he hoped to create. (Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's—1917)

In January and February 1858 he spent a month at the home of Frederick Douglass, planning his raid and writing a provisional constitution for the revolutionary state Brown hoped to create. Brown begged Douglass to join him. Douglass was sympathetic to Brown's goals but believed the plan was suicidal: "You're walking into a perfect steel-trap and you will never get out alive," he told Brown. Nevertheless, Douglass introduced Brown to Shields Green, a fugitive slave from South Carolina who joined Brown—and whom Virginia authorities hanged after the raid.

In the early spring of 1858, Brown began raising large amounts of money for his raid, writing potential backers that he was planning some "[underground] Rail Road business on a somewhat extended scale." However, in person he made it clear that he intended to do more than merely help large numbers of slaves to escape. On February 22, 1858, Brown revealed his general plans—and his provisional constitution—to Gerrit Smith and Franklin Sanborn. Brown also contacted black leaders to help recruit free blacks. In March 1858 Brown met in Boston with the Reverend Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker, George Stearns, Samuel Gridley Howe, and Franklin Sanborn. These five, along with Smith, made up the "Secret Six," Brown's primary financial backers. In June 1858, traveling as "Shubel Morgan," Brown headed west, raising more money and recruiting more raiders in Cleveland. While Brown continued on to Kansas, John E. Cook, one of his raiders, moved to Harpers Ferry, where he found work and learned what he could about the community, the armory, and the lay of the land. He also fathered a child and married a local woman.

In December 1858 Brown once again made headlines for his exploits in the West. He invaded Missouri, where he killed a slave owner, liberated 11 slaves, and brilliantly evaded law enforcement officers as he led the freed blacks to Canada. There Brown met a black printer, Osborne Perry Anderson, who would later take part in the Harpers Ferry raid. Although a wanted man with a price of $250 on his head, Brown returned to the United States, traveling and speaking in Ohio, New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Brown also contacted the "Secret Six" who were financing him.

In June 1859 Brown visited his home in North Elba, New York, for the last time, where he said good-bye to his wife and daughters. Brown probably knew that he was unlikely to see his family again, something he stoically accepted as a cost of his crusade against slavery. He was less accepting of his son Salmon, however, who decided he would not join his father on an apparently suicidal mission into Virginia.

Brown and his sons Oliver and Owen arrived in Harpers Ferry on July 3, 1859, and Brown rented a farm in Maryland, about seven miles from Harpers Ferry. He expected large numbers of men to enlist in his "army," but by September only 18 had arrived, including another of Brown's sons, Watson. By mid-October, a few more arrived.

On Sunday, October 16, Brown and his men began their raid. They made a strange assortment: veterans of the struggles in Kansas, fugitive slaves, free blacks, transcendental idealists, Oberlin College men, and youthful abolitionists on their first foray into the world. The youngest was 18. The oldest, Dangerfield Newby, was a 44-year-old fugitive slave from Virginia who hoped to rescue his wife from bondage. But most of the raiders were in their 20s, half the age of their leader, the 59-year-old Brown. Brown left three of his recruits to guard their supplies and arms at the farmhouse in Maryland. The remaining 18 raiders, 13 whites and five blacks, marched with John Brown to Harpers Ferry.

Brown's small army arrived in Harpers Ferry at night and quickly secured the federal armory and arsenal and later Hall's Rifle Works, which manufactured weapons for the national government. With the telegraph wires cut, Brown might have easily seized the weapons in the town, liberated slaves in the neighborhood, and then taken to the hills. Or he might have destroyed the armory and literally blown up the town.

Inexplicably, though, he remained in the armory, waiting for slaves to flock to his standard. They never came. Instead, townsmen and farmers surrounded the armory. These civilians were probably not strong enough to dislodge Brown, but they kept him pinned down. Although Brown tried to negotiate with the civilians, his emissaries, including his son Watson, were shot while under a white flag. By the morning of October 18, eight of Brown's men were dead or captured, and that same day militia from Virginia and Maryland arrived. President James Buchanan had dispatched U.S. marines and soldiers to Harpers Ferry, with Brevet Colonel Lee in command. Directly under Lee was another Virginian, Lt. J.E.B. Stuart.

That morning, marines stormed the engine house of the armory, capturing Brown and a few of his raiders and killing the rest. By the end of the raid, of the 22 who had been involved in the plot, 10 of Brown's men, including his sons Watson and Oliver, were dead or mortally wounded; five, including Brown, had been captured. Seven escaped, but two were later captured in Pennsylvania and returned to Virginia for trial and execution. The other five, including Brown's son Owen, made their way to safe havens in Canada and remote parts of the North. All but Owen Brown later served in the Union Army.

Brown's capture on October 18 set the stage for his trial and execution. Severely wounded, Brown had to be carried into court on October 25 for a preliminary hearing and on October 27 for his trial. The judge would not even delay the proceedings a day to allow Brown's lawyer to arrive. The trial was speedy. On November 2 Brown was convicted and sentenced to death. He was executed on December 2, and on December 8 he was buried at the family farm in North Elba, near Lake Placid. Many Northerners interpreted the hasty actions of the Virginia authorities in trying and executing Brown as another example of Southern injustice. The apparent lack of due process in his trial thus contributed to the Northern perception that Brown was a martyr. The most absurd aspect of the trial was the charge against Brown. He was indicted and convicted of "treason" against the state of Virginia. But as Brown pointed out, he had never lived in Virginia, never owed loyalty to the state, and therefore could not have committed treason against the state. Most Southerners, however, saw Virginia's actions as a properly swift response to the unspeakable acts of a dangerous man whose goal was to destroy their entire society.

Brown's grave at his family farm in North Elba, New York, became a pilgrimage site. (Library of Congress)

By the time of his execution, the entire nation was fixated on this bearded man who spoke and looked like a biblical prophet and whose deeds thrilled—whether with fear or admiration or both—an entire generation.

Indicative of this fixation is a shared aspect in the otherwise divergent responses of Wendell Phillips and Edmund Ruffin—the great abolitionist orator and the fire-eating Virginia secessionist. In the year following the raid, each of them prominently carried and displayed a "John Brown pike" that Brown had ordered from the Connecticut foundry. For Phillips the pike symbolized the glory, and for Ruffin the horror, of a servile insurrection led by a resurrected Puritan willing to die to overthrow slavery.

Terrorist, Guerrilla Fighter, Revolutionary?

Brown's actions in Kansas and at Harpers Ferry were clearly violent. He killed people or at least supervised their death. But was he a terrorist? At neither place do his actions comport with what we know about modern terrorists.

The Harpers Ferry raid was his most famous act. Brown held Harpers Ferry from late Sunday night, October 16, until he was captured on the 18th. He was in possession of almost unlimited amounts of gunpowder and weapons. He had captured prominent citizens, most famously Colonel Washington. He stopped a train full of passengers and freight.

What would modern terrorists have done in such circumstances? They might have let the train go, only after they had robbed all the passengers to fund further acts of terror, and then blown up the bridge as the train crossed from Virginia to Maryland. They might have planted explosives on the train and let it proceed, as terrorists did in Spain a few years ago. What did Brown do? He boarded the train, let people know who he was, and was seen by people who might later have identified him. Then he let the train continue on to Washington. These were not the actions of a terrorist.

While in Harpers Ferry, Brown might have blown up the federal armory (or indeed most of the town) after taking as much powder and weapons as his men could carry. He might have broken into homes of prominent people and slaughtered them. Brown did none of these things. He waited, foolishly for sure, for the slaves in the area to flock to him. He was caught in a firefight with local citizens, and he was captured by the U.S. forces. He proved to be a disastrous military leader and a failed "captain" of his brave and idealistic troops. But he never acted like a terrorist. He ordered no killings; he did not wantonly destroy property; and he cared for his hostages. This is simply not how terrorists act.

The events at Kansas are similar. Brown targeted a number of individuals who had been leading—violently leading—proslavery forces in the area.

At the home of James Doyle, the raiders did not kill his 16-year-old son or his wife, Mahala, even though both could have identified Brown and his men. Brown's men killed Allen Wilkinson, but not his wife, Louisa, who recognized one of Brown's sons from his voice. Mrs. Wilkinson was ill at the time, and after killing her husband, Brown asked her if there would be neighbors who could help care for her.

Surely, as Robert McGlone notes, it might seem "bizarre" that Brown was concerned about her health after he had just killed her husband. But her husband was guilty of attacking free state men and threatening the Browns, and so he was (in John Brown's mind) justly executed. But his wife was innocent and not punished. This was not the behavior of a terrorist.

Kansas—Bleeding Kansas as it is known—was in the midst of a civil war. Between 1855 and 1860 about 200 men would be killed in Kansas. Not all were politically motivated, and historians disagree on what constitutes a "political" killing. But even the most conservative scholar of this violence finds 56 killings that were tied to slavery and politics. I think this number is low, and that most of the 200 deaths were actually politically motivated and tied to slavery and Bleeding Kansas. But the actual number of political killings is less important than the understanding that in Kansas there was a violent civil war being fought over slavery; men on both sides were killed. Brown's actions are most famous because there were five killings, and he strategically used swords, rather than guns, which would have alerted neighbors. This is the nature of guerrilla warfare. It is brutal and bloody, but it is not terrorism.

There is also a political context. In Kansas there was no democratic government. Elections were notoriously fraudulent and violent. The majority of the settlers were from the free states, but the national government recognized a minority government that was proslavery. That legislature made it a crime to publicly oppose slavery. There was, at least under the formal law, no free speech in Kansas for abolitionists. This was also true in Virginia, when John Brown raided Harpers Ferry. He could not have gone to Virginia to denounce slavery or even urge Virginians to give up slavery. Thus, in this sense Brown was not fighting against democratic institutions in a free society; rather he was fighting against an unfree society that denied him basic civil liberties and, in Kansas, even the right to have a fair election.

Remembering, Honoring, John Brown

So, what in the end can we make of John Brown? If he was not a terrorist—what was he? He might be seen as revolutionary, trying to start a revolution to end slavery and fulfill the goals of the Declaration of Independence. As proslavery border ruffians tried to prevent democracy in Kansas, and were willing to murder and assault supporters of freedom, John Brown surely had a right to defend his settlement and his side. Brown did not carefully plan the Pottawatomie raid the way Terry Nicholas and Timothy McVeigh planned the Oklahoma City bombing. He reacted to specific threats and the sacking of Lawrence by a proslavery mob. This was not terrorism, but a fact of warfare in Bleeding Kansas. Nevertheless, modern Americans are uncomfortable endorsing his vengeful violence in Kansas, however necessary it may have been.

Similarly, no one, not even the slaveholders, could deny that slaves might legitimately fight for their own liberty. If slaves could fight for their liberty, then surely a white man like Brown was not morally wrong for joining in the fight against bondage. Thus Harpers Ferry is in the end a blow for freedom, against slavery. Who can deny the legitimacy of such a venture, however foolish, poorly designed, and incompetently implemented? But in a society of democratic traditions, Americans recoil at the idea of violent revolution and raids on government armories, even when, as was the case in Virginia in 1859, democracy was something of a sham, and there was neither free speech nor free political institutions.

In the end, we properly view Brown with mixed emotions: admiring him for his dedication to the cause of human freedom, marveling at his willingness to die for the liberty of others, yet uncertain about his methods, and certainly troubled by his incompetent tactics at Harpers Ferry.

Perhaps we end up accepting the argument of the abolitionist lawyer and later governor of Massachusetts, John A. Andrew, who declared "whether the enterprise of John Brown and his associates in Virginia was wise or foolish, right or wrong; I only know that, whether the enterprise itself was the one or the other, John Brown himself is right."

Paul Finkelman received his B.A. from Syracuse University and his Ph.D. in history from the University of Chicago. He is the President William McKinley Distinguished Professor of Law and Public Policy at Albany Law School. He is the author or editor of more than 25 books and over 150 scholarly articles. His legal history scholarship has been cited by numerous courts, including the United States Supreme Court.

Note on Sources

The very best discussion of Brown in Kansas is found in Robert E. McGlone, John Brown's War Against Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

The quotation from Brown's speech in court is from Life and Letters of John Brown, Liberator of Kansas, and Martyr of Virginia, ed. Franklin B. Sanborn (1885), p. 585. Quotations of Frederick Douglass and Brown are from Stephen B. Oates, To Purge This Land With Blood: A Biography of John Brown, 2nd ed. (Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 1984), p. 335. For more on Brown's self-created martyrdom, see Paul Finkelman, His Soul Goes Marching On: Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995), pp. 41–66.

For the conservative estimate of the number of political killings in Kansas, see Dale E. Watts, "How Bloody was Bleeding Kansas? Political Killings in the Kansas Territory, 1854–1861," Kansas History, 18 (1995): 116–129.

John Andrew's declaration that "John Brown himself is right" is quoted in Owald Garrison Villard, John Brown, 1800–1859: A Biography Fifty Years Later (New York Alfred A. Knopf, 1943), p. 557.

Articles published in Prologue do not necessarily represent the views of NARA or of any other agency of the United States Government.

CALL FOR PAPERS - Women and Film in Africa Conference: Overcoming Social Barriers. Organised by the Africa Media Centre, University of Westminster

CALL FOR PAPERS - Women and Film in Africa Conference: Overcoming Social Barriers. Organised by the Africa Media Centre, University of Westminster