Live Unchained had the pleasure to interview Kameelah Rasheed. She is a documentary-based photographer and co-founder of Mambu Badu, a photography collective that highlights female photographers of African descent. Kameelah discusses her photography and inspiration here. Her work tells the stories of people from South Africa to New York.

Can you tell us a little about yourself and background?

In a small Bay Area neighborhood named East Palo Alto, I was raised on a harmonious, yet eclectic mix of Islam, old Gil Scott-Heron records, and tofu as the other white meat. I was the black nerdy kid who read too much, hung out in the science lab selecting daphnia from the Carolina Biological company catalog for the next science fair, and wore cornrows with beds when perms were the norm. By the time I got to high school, I was 13 and the sole Muslim kid at an elite private Catholic school and one of maybe eight other black students on scholarships. I graduated from high school at 16 and attended Pomona College, a small elite liberal arts college in Claremont, CA. There I studied Public Policy and Africana Studies graduated as a Harry S Truman Scholar, Rockefeller Brothers Fund Fellow, and Phi Beta Kappa. During my senior year, the U.S. State Department awarded me with a U.S. Fulbright Grant to study urban planning and housing in Johannesburg, South Africa.

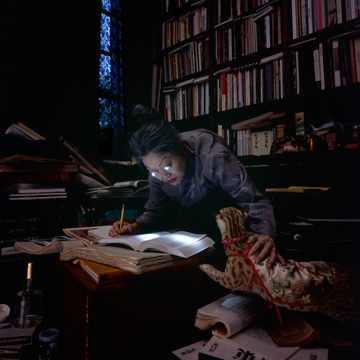

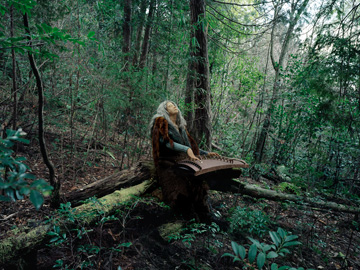

Throughout my education, I loved to tell stories and focused solely on written narratives. It was not until I moved to South Africa that I explored the possibility of telling stories with photographs. When I lived in Cape Town, South Africa as an exchange student in 2005, I photographed the children I worked with at the orphanage. When I moved to Johannesburg in 2006, I began to photograph townships, nation-wide strikes, political events, community events, and city life. I was eager and insatiable. I was learning and lacked the confidence to take more risks. Despite being in a few gallery shows, I did not take on the title of “photographer” until a few months ago. Now, I consider myself a documentary-based photographer. Simply, I like to tell the stories of “regular” people through photographs. I also love poetry especially Harryette Mullen, e.e. cummings, Emily Dickinson, and Yusef Komunyakaa. I imagine photographs as a visual poetry with it’s own set of grammar rules that should be broken at times. In my mind, the power of a poem is the achievement of depth through some clever manipulation of brevity. The same goes with photographs.

Can you tell us a little about your creative process?

Do you carry around your camera wherever you go,

or do you set out to shoot something in particular?

Last night, I walked pass a group a young Caribbean boys and girls talking to a young group of Hasidic boys in Crown Heights. The juxtaposition of skinny jeans, Caribbean accents, and brown skin with black suits, Yiddish phrases, and peyes was something worthy of several shots and an interview. These moments fascinate me. I was curious. Whenever my curiosity is peeked, I shoot. Unfortunately, it was too dark to shoot, but am looking forward to similar opportunities.

And yes, I carry my loves with me everywhere. I used to carry three cameras, but I now limit it to EZRA, my Nikon D90.

Do you have a place where you enjoy photographing the most?

Anywhere and everywhere. Photographing somewhere unfamiliar is always a lot of fun. It forces you to take risks and become more familiar with the community.

Your photography from South Africa is particularly compelling! Can you tell us more about those pieces? What did you learn and experience there?

I lived in South Africa on two occasions. First in 2005, I was an exchange student at the University of Cape Town. When I graduated from college in 2006, the U.S. State Department awarded me as an Amy Biehl U.S. Fulbright Scholar to South Africa. I lived there for 9 months from 2006-2007. This was the best 9 months of my life.

Many of the photographs are from local as well as countrywide protests and friends. I hung out with a sundry collection of folks in Johannesburg: activists, photographers, printmakers, writers, a rasta or two, and a hip-hop group. There was plenty of inspiration. More than anything, I felt really comfortable and complete in Johannesburg. I shot with the thought in mind, “What do I want to show my family and students about South Africa? How can I articulate how at home I feel here?” At the time I did not have a DSLR but a clunky point and shoot. I loved it.

As a graphic designer, I’m always intrigued by photography, because it has a way of capturing raw, instantaneous moments in a way that is different from other art forms. What are your thoughts on the power of photography?

I think the power of photography is the ability to present a fragment of reality while presenting the opportunity for another reality to exist in that same space. Photography has the power to change us from spectator to engaged advocate. Photographs are supposed to reflect or even just be constitutive of some reality. They are by no means objective, but they capture something “real.” Even when you look at an image of a starving child or young refugee, you are confronted with reality of that situation, but photography also pushes you to want to change that image. A friend asked me what good art was. I told him that I believe good art is anything that causes you to pause and rethink your next set of behaviors. I think good photography has this power.

You are a history teacher. Does having a knowledge of history influence your thoughts on photography and/or your artwork?

More than having any particular historical knowledge, being a lover of history is about curiosity and chasing after that hidden story. This is what I teach my students in Crown Heights. As a photographer, I think about taking photographs that tell a story that gives voice to that marginal narrative. Because I approach photography as a storyteller, I believe formal and informal interviews of the people I photograph are central. I am in the process of beginning a project with an audio-based component for each photograph. Also, I believe doing research before and after shooting is important. I want to know what kinds of narratives (written and visual) have already been captured so that I give some love and shine to narratives that have received less attention.

Being a historian allows me to be conscious of my relationship to the people I am photographing. It’s no longer about creating an image; it becomes an opportunity to create new relationships between human beings if only for that moment. I want to express my love for humanity and steer clear of exploitative shots that reinforce existing stereotypes…and I want to do this while staying true to what I see in that moment. I do not want my shots to be decontextualized ethnographic shots.

Do you have a community of artists around you that help feed your creativity? How do you push yourself to produce your very best work?

Having moved to New York only 3 months ago, the physical community is still developing and I feel inspired by everyday scenes that push me to think about how to craft a photograph that tells a story. Back home in California, my family was a great source of support.

One source of inspiration has been Mambu Badu, a photography collective founded by Allison McDaniel, Daniel Scruggs and myself. Mambu Badu is a photography collective that seeks to find, expose, and nurture emerging female photographers of African descent. “Mambu Badu” is an adaptation of the KiSwahili phrase “Mambo Bado” which is loosely translated as “the best has yet to come.” At this moment, we dwell in an exciting space of possibility where we can grow as artists. We invite other female photographers of African descent to join us in this journey. We are approaching our art and this collective with a humble heart, a curious nature, and a persevering spirit.

You live in New York. How does the character and environment of New York influence your work?

New York reminds me to look at the details and to find beauty in the mundane. Things are much busier than my small California town of 30,000 people. The fast pace of this city makes photography even more intriguing—the opportunity to slow time down…just a bit.

Can you share with us some of your photography?

"Black Girl Pain," 2010 (Brooklyn, NY)

"Regina," 2008 (Protea Glen-Johannesburg, South Africa)

"Yellowman," 2008 (Newtown-Johannesburg, South Africa)

"Kele," 2010 (Brooklyn, New York)

“Sunset,” 2008 (Protea Glen-Johannesburg, South Africa)

“Sulaiman,” 2010 (Brooklyn, New York)

“Un Secreto,” 2010 (East Palo Alto, California)

“Blow,” 2010 (East Palo Alto, California)

“Hujjaj,” 2008 (Oakland, California)

“Jabu,” 2008 (Downtown Johannesburg, South Africa

“Public Sector Strike,” 2007 (Pretoria, South Africa)

“Second Helpings,” 2010 (New York, New York)

What does living unchained mean to you?

Living unchained is not waiting for permission to be great.