President Jean_Bertrand Aristide interviewed by Nicolas Rossier, November 2010

Exiled Former President of Haiti Talks with Filmmaker Nicolas Rossier

Saturday, November 13, 2010

" When we say democracy we have to mean what we say"

Currently in forced-exile in South Africa, former Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide is still the national leader of Fanmi Lavalas – one of Haiti's most popular political parties. A former priest and proponent of liberation theology, he served as Haiti's first democratically elected president in 1990 before he was ousted in a CIA backed coup in September 1991. He returned to power in 1994 with the help of the Clinton administration and finished his term. He was elected again seven years later, only to be ousted in a coup in February 2004. The coup was lead by former Haitian soldiers in tandem with members of the opposition. Aristide has repeatedly claimed since, that he was forced to resign at gunpoint by members of the US Embassy. US officials have claimed that he decided to resign freely following the violent uprising. He now lives in exile in South Africa where he still waits to get his diplomatic passport renewed. He is not allowed to travel outside South Africa.

Aristide is still the subject of many controversies. He is reviled by the business elite and feared by the French and American governments, who deem his populism dangerous. But he remains loved by a large portion of the Haitian population.

In a June 10 report to the Committee on Foreign Relations, "Haiti: No Leadership – No Elections”, ranking Republican member Richard Lugar denounced the systemic injustice of excluding his Fanmi Lavalas party.

Last week, independent reporter and filmmaker Nicolas Rossier, conducted an exclusive two-hour interview with former Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in the hills of Johannesburg. He spoke with the former President about his life in forced exile, Haiti’s current political situation, and his possible return to Haiti. This is an excerpt of the interview. The interview is re-posted here, to the website of the Canada Haiti Action Network, with permission of Nicolas Rossier.

*****************************************************

Mr. President Aristide, thank you for having me today. My first question is about the earthquake that took place in Haiti in January of 2010. Can you tell me how and when you learned about the tragedy?

It was morning here. I was at Witwatersrand University here in Johannesburg to work in the lab of the Faculty of Medicine for Linguistics and Neuroanatomy. I realized that it was a disaster in Haiti. It was not easy to believe what I was watching. We lost about 300,000 people, and in terms of the buildings, they said that about 39% of the buildings in Port-au-Prince were destroyed, including fifty hospitals and about 1,350 schools.

Up until today they have cleared only about 2% of these 25 million cubic meters of rubble and debris. So this was a real disaster. We could not imagine that Haiti, already facing so many problems, would now face such a disaster. Unfortunately this is the reality. I was ready to go back to help my people, just as I am ready to leave right now if they allow me to be there to help. Close to 1.8 million victims are living in the street homeless. So this is a tragedy.

Your former colleague, the current President René Préval, was highly criticized after the earthquake for being absent. Overall, he was judged as not having shown enough leadership. Do you think that’s a fair criticism?

I believe that January 12, 2010 was a very bad time for the government and for the Haitian people. To have leadership, yes it was necessary, overall, to be present in a time of disaster like this one. But to criticize when you aren’t doing any better is cynical. Most of those who were criticizing him sent soldiers to protect their own geopolitical interests, not to protect the people. They seized the airport for their own interests, instead of protecting the victims – so for me there should be some balance.

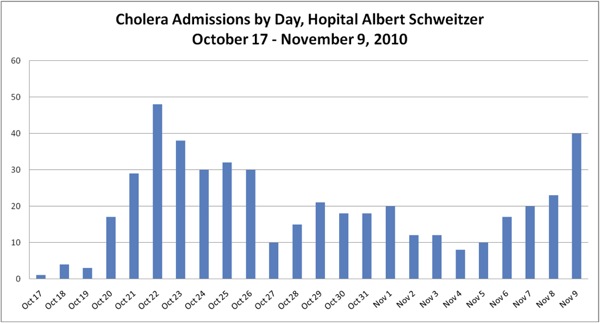

Can you give us your thoughts on the recent cholera epidemic?

As for this recent incident of cholera, whether or not it was imported – as the evidence strongly suggests – it’s critical. First, those who organized the coup d’état/kidnapping of 2004, paving the way for the invaders now accused as having caused the recent outbreak of cholera, must also share the blame. Second, the root causes, and what facilitated the deadly spread of the disease are structural, embedded in Haiti’s historical impoverishment, marginalization and economic exploitation. The country’s once thriving rice industry – destroyed by the subsidized US rice industry in the 1980s – was in the Artibonite, the epicenter of the cholera outbreak. The near destruction of our rice industry coupled with the systematic and cruel elimination of the Haitian pigs rendered the region and the country poorer. Third, in 2003 our government had already paid the fees on an approved loan from the InterAmerican Development Bank to implement a water sanitization project in the Artibonite. As you can remember, that loan and four others were blocked as part of a calculated strategy by the so-called friends of Haiti to weaken our government and justify the coup d’état.

Many observers in Haiti and elsewhere keep asking me the same question, which is this: what are you doing here and what prevents you from coming back to your own country? The Haitian constitution does not allow political exile. You have not been convicted of anything, so what prevents you from going back? You are a Haitian citizen and should be allowed to move freely.

When I look at it from the South African perspective, I don’t find the real reasons. But if I try to understand it from the Haitian perspective, I think that I see the picture. The picture is that in Haiti, we have the same people who organized the invasion of 2004 after kidnapping me to put me in Africa. They are still there. That means there is a kind of neo-colonial occupation of 8,900 UN soldiers with 4,400 policemen spending, more or less, fifty-one million US dollars a month in a country where 70% of the population lives with less than a dollar a day. In other words it’s a paradise for the occupiers. First we had the colonization of Haiti and now we have a kind of neo-colonial occupation of Haiti. In my view, they don’t want me back because they still want to occupy Haiti.

So you see the elite in Haiti basically influencing those currently in power and pressuring them to prevent you from coming back? There is certainly a more friendly administration now in Washington. Are they still sending the same messages to South Africa regarding you?

JBA: No … (laughs)

I heard that you tried to go to Cuba for an urgent eye surgery and you were not allowed to go. Is this true?

Allow me to smile…(laughs) because when you look at this, you smile based on the contradiction that you observe in the picture. They pretend that they fear me when I am part of the solution, based on what the majority of the people in Haiti still continue to say. If they continue to ask for my return by demonstrating peacefully, that means you still have the problem. So if you want to solve the problem, open the door for my return.

Before the coup, I was calling for dialogue in such a way to have inclusion, not exclusion - to have cohesion, not an explosion of the social structure. The opposition, with foreign backers, decided to opt for a coup and the result is what I would say in a Hebrew saying: ?? ??? ?? ???? , in English meaning, “things went from bad to worse.” So if you they are wise, they should be the first to do their best for the return because the return is part of the solution, not part of the problem.

You have said that you do not intend to become involved in politics, but rather return as a citizen. Is that your vision?

Yes, and I said it because this is what I was doing before being elected in 1990. I was teaching and now I have more to offer based on my research in linguistics and neurolinguistics, which is research on how the brain processes language. I have made a humble contribution in a country where once we had only 34 secondary schools when I was elected 1990, and before the coup of 2004 we had 138 public secondary schools. Unfortunately the earthquake destroyed most of them. Why are they so afraid? It’s irrational. Sometimes people who want to understand Haiti from a political perspective may be missing part of the picture. They also need to look at Haiti from a psychological perspective. Most of the elite suffer from psychogenic amnesia. That means it’s not organic amnesia, such as damage caused by brain injury. It’s just a matter of psychology. So this pathology, this fear, has to do with psychology, and as long as we don’t have that national dialogue where fear would disappear, they may continue to show fear where there is no reason to be afraid.

What has to be done for you to be able to return to Haiti? What do you intend to do to make that happen? It’s been six years now. It must be very tough for you not to be able to return with your family. You must feel very homesick.

There is a Swahili proverb which says: “Mapenzi ni kikohozi, hayawezi kufichika” - or “love is like cough that you cannot hide.”

I love my people and my country, and I cannot hide it, and because of that love, I am ready to leave right now. I cannot hide it. What is preventing me from leaving, as I said earlier, if I look from South Africa, I don’t know.

But when you ask the question to the people responsible here, they say they don’t know.

Well (pause) I am grateful to South Africa, and I will always be grateful to South Africa and Africa as our mother continent. But I think something could be done in addition to what has been done in order to move faster towards the return, and that is why, as far as I am concerned, I say, and continue to say that I am ready. I am not even asking for any kind of logistical help because friends could come here and help me reach my country in two days. So I did all that I could.

Do you think that the Haitian government is sending signals to the South African government that they are not ready? For instance, maybe they do not want you to return because they are concerned about security issues for you. The Haitian government may not be able to ensure your security. There are some individuals who, for ideological reasons, don’t support you and could go as far as to try to assassinate you. Is that part of the problem?

In Latin they say: “Post hoc ergo propter hoc” or "after this, therefore because of this." It’s a logical fallacy. In 1994, when I returned home, they said the same: if he comes back the sky will fall. I was back during a very difficult time where I included members of the opposition in my government, moving our way through dialogue in order to heal the country. But unfortunately we did not have a justice system, which could provide justice to all the victims at once. However slowly, through the Commission of Truth and Justice, we were paving the way to have justice. Now I will not come back as a head of state, but as a citizen. If I am not afraid to be back in my country, how could those who wanted to kill me, who plotted to have the coup in 2004, be the first to care about my security? It’s a logical fallacy. (laughs) They are hiding, or try to hide themselves behind something that is too small…no no no no.

Are they afraid of your political influence – afraid that you can affect change?

Yes, and I will encourage those who want to be logical (laughs), not to fear the people, because when they say they fear me, basically it’s not me. It’s the people, in a sense that they fear the votes of the people. They fear the voice of the people and that fear is psychologically linked to a kind of social pathology. It’s an apartheid society, unfortunately, because racism can be behind these motivations.

I can fear you, not for good reasons, but because I hate you and I cannot say that I hate you. You see? So we need a society rooted in equality. We are all equal, rich and poor and we need a society where the people enjoy their rights. But once you speak this way, it becomes a good reason for you to be pushed out of the country or to be kidnapped as I was (laughs). But there is no way out without that dialogue and mutual respect. This is the way out.

In your view, what is the last element missing for you to go back? You said there was one more thing they could do for you do go back. Can you tell us that?

They just need to be reasonable. The minute they decide to be reasonable, the return will happen right away.

And that means one phone call into the US State Department ? One green light from one person? Technically, what does that mean?

Technically I would say that the Haitian government, by being reasonable, would stop violating the constitution and say clearly that the people voted for the return as well. The constitution wants us to respect the right of citizens, so we don’t accept exile. That would be the first step.

Now if other forces would oppose my return, they would come clear and oppose it but as long as we don’t start with a decision from the Haitian government, it makes things more difficult.

So the first gesture has to come from the Haitian government?

Yes

And they could make this happen by telling the US State Department you should be allowed to come back, and should come back.

They would not have to tell the State Department.

So it’s not a political decision in Washington? It’s between the Haitian government and the South African government?

As a matter of fact, I don’t have a passport because it is expired. I have the right to a diplomatic passport. By sending me a normal diplomatic passport there would be a clear signal of their will to respect the constitution.

But it’s the Haitian government that has to do that?

Yes

Or they could just renew your Haitian passport?

Yes

Ask you for a new photo of yourself and issue a new passport?

(laughs) You see why when I said earlier that we should not continue to play as a puppet government in the hands of those who pretend to be friends of Haiti. I am right because as long as we continue to play like that we are not moving from good to better or good to good, but from bad to worse.

There was a lot of noise lately in the US media about the candidacy of singer Wyclef Jean, who eventually was denied running by the CEP (Haiti's Interim Electoral Commission). Any comment about the whole commotion around his candidature?

When we say democracy we have to mean what we say. Unfortunately, this is not the case for Haiti. They talk about democracy but they refuse to organize free and fair democratic elections. Is it because of a kind of neocolonial occupation? Is it because they still want exclusion and not inclusion that they refused to organize free and fair democratic elections?

Last year, we observed that they said they wanted to have elections, but in fact they had a selection and not an election. Today they are moving from the same to the same. They are not planning to have free and fair democratic elections. They are planning to have a selection. They excluded the Lavalas* party, which is the party of the majority. It is as if in the US they could organize an election without the Democrats. So from my point of view, Wyclef Jean came as an artist to be a candidate and it was good for those who refuse elections because they could have a “media circus” in order to hide the real issue, which is the inclusion of the majority. So this is my view of the reality.

Looking back at the dramatic events that lead to your overthrow in 2004, is there anything in hindsight that you wished you had not done? Anything tactically or strategically that you wish you had done differently and that could have prevented the coup?

If I could describe the reality from that day in 2004 to today, you would allow me to use the Hebrew phrase again (speaks in Hebrew), which means “from bad to worse”. That is how it has been from 2004 to today. When we look at that coup d’état, which was a kidnapping, I was calling for dialogue and they manipulated a small minority of Haitians to play the game of moving from coup d’état to coup d’état, instead of moving to free and fair democratic elections. The first time Haiti had free and fair democratic elections was 1990, when I was elected. Then we wanted to move from elections to elections. So in 2004, we were moving towards a real democracy and they said no. The minority in Haiti – the political and economic elite – is afraid of free and fair elections, and their foreign allies don’t want an election in Haiti. That is why they excluded Famni Lavalas. As long as they refuse to respect the right of every citizen to participate in free and fair democratic elections, they will not fix the problem.

That is an interesting answer, but I was more thinking of strategic mistakes you made such as asking France to pay reparation in 2003. In doing that, you lost a natural ally that could have stood with you before the coup and within the United Nations Security Council to protect your government. In fact, France stood with the US and did not come to your rescue this time, probably because they were very upset by your demand for restitution.

I don’t think this is the case. The first time I met with French President Jacques Chirac, I was in Mexico. At that time he was with Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin. I invited them to join us to celebrate freedom as a universal value. So that was an opportunity for France to realize that yes, Haiti and France can stand up together to celebrate freedom as a universal value.

In 1789, when France had their revolution, they declared “liberty, equality, fraternity” for all people, but in the back of their minds slaves were not human beings. To them neither Haitian nor African slaves were human. We fought hard and we got our independence; it was not a gift. It was the blood of our forefathers that was shed to gain our freedom. Despite that, we did not want to celebrate our 200 years of independence with any kind of spirit of vengeance, nor a spirit of glory to remind France of what they had done. It wasn’t that. It was an invitation to celebrate freedom as a universal value. So that would give a wonderful opportunity for France if they wanted to do it together. That would not exclude the truth because the truth is they obliged Haiti to pay 90 million francs, which for us today, is more than 21 billion USD. This is restitution, not reparation.

In 2001, here in Durban South Africa, the UN gave the Haitians and French an opportunity to address this issue of reparation. The French refused, but we respectfully asked them to let us have an opportunity to address this issue in a mutually respectful way. In one word – if today I were the President of Haiti, as I was in 2004, I would ask France to join Haiti to celebrate freedom, but also to address this issue of 21 billion USD. As a matter of fact, a head of state elected by his people must respect the will of the people. When President Sarkozy went to Haiti after the earthquake, Haitians were not begging for cents, they were asking for the 21 billion USD because it is a question of dignity. Either we have dignity or we don’t, and Haitians have dignity. That means we respect your dignity, so you should also respect our dignity. We will not beg for cents. Cents will never solve the problems of Haiti. After 200 years of independence, we are still living in abject poverty. We still have what we had 200 years ago in terms of misery. It is not fair. So if we want to move from misery to poverty with dignity, France must address this issue with Haitians and see what kind of agreement will come out from this important issue.

But don’t you think now, with hindsight, that this may have cost you your presidency?

It could be part of the picture but I don’t think it was the main reason.

If France had asked the UN Security Council to send UN peacekeepers to maintain your government, do you think you would not have been pushed out of power?

Sometimes you know there are diplomatic words to cover something else. I think at the time, the burning issue was Iraq.

France opposed the US on this issue and that was a golden opportunity for them to sacrifice Haiti in terms of leading and participating in a coup or in the kidnapping of a president.

But the real reason underneath was that France did not want you to annoy them anymore with this request. 2003 was the first time, at least publicly and officially, that a Haitian President made such a request.

I smile because former colonists defend their interests, not their friends. Even if they call themselves friends of Haiti, they will always continue to defend their own interests.

We could compare what is going on right now today, post-earthquake, to what was going on in 2004, in order to find out if France is really helping Haiti and if they would change their policy or not. From my point of view, they would not change their policy because they have enough in front of them, in terms of the disaster, to address the issue of 21 billion USD now. But they still don’t want to, meaning that if they don’t want to address it today after what happened in Haiti in January 2010. I don’t think they would have changed their policy in 2004.

That is my way to read it. But maybe one day the French government will take up the issue because men can change if they want to change. I wish they would change their policy to respectfully address the issue with Haiti, because it’s a must.

As a matter of fact, as soon as Gérard Latortue was placed as Prime Minister after your removal, the Haitian government dropped the issue right away.

But that did not kill the issue (laughs). If we look at the history of Haiti before 2004, no one dared to address the issue, but we were moving from misery to poverty with dignity. Then when we addressed the issue they did not want to answer – but that does not kill the issue. It means that it will remain a reality as long as they refuse to address it.

My wish is that, one day, they will realize that they have to do it. What happened with Italy and Libya? Italy addressed the issue of reparation and that was good for both countries. The same way that we must address with France the issue of restitution.

I remember a recent article from Jacqueline Charles in the Miami Herald where an historian was quoted as saying: “Lavalas was never a party. It was a movement, which is now in deep crisis and divided among distinct factions led by some of its old barons'' …They all want the Lavalas vote without appealing to Aristide. So, yes, Lavalas as we knew it is dying a slow death.'' He was commenting on the current debate around the future elections in Haiti. What do you think of what he said?

Some people pretend they are experts on Haiti but they often act like people suffering from social amnesia. When you take a group of mice and you put them in a lab, if these mice don’t have the capacity of producing oxytocin in the brain, they are not able to recognize other mice. That is how it is, it is a fact. These people suffer from social amnesia. They are unable to recognize Haitians as human beings because of our color, our poverty and misery. The majority of the Haitian people declared “Lavalas is our political party.” That is what the majority said and they have their constitution, so how can someone pretend that it’s not? These people, from my humble point of view, act as if they were mental slaves, meaning they have their masters giving them financial resources to say this, and they can cover themselves under a “scientific” umbrella, when in fact they are mental slaves.

So there is this amnesia because most commentators admit that Préval won in 2006 thanks to the Lavalas base. Many in Haiti want to use Lavalas as well to win, but nobody wants the Lavalas party to win or mention your name in the process. How do you feel about this contradiction?

Unfortunately, what South Africa had before 1994 is what Haiti still has as a reality today. The structure of apartheid is still rooted in the Haitian society. When you have apartheid, you don’t see those behind the walls. That is the reality of Haiti. The people exist, but they don’t see the people and they don’t want to see them. That is why they don’t count them. They want to use them, but they don’t want to respect their will.

When they talk about Lavalas and the Haitian people, they fear them because if there is a fair election the people will defeat them. So they have to exclude the Lavalas party or the majority, in order to make sure that they will select what they want to select. So this is the kind of apartheid that they have in Haiti. If you say that, they will hate you and they may try to kill you. It is because they don’t want you to see the reality. Why do I say this? It’s because I love my country. If you have a cancer and refuse to call it a cancer, it will kill you. You better accept it and find a way to prevent death. That is what I want for my country.

But there has been some opportunism lately. We saw people like your former friend and later foe Evans Paul asking for your return. They are using you to get support from the Lavalas base. Or many want to appeal to Lavalas but are scared to mention you. What is your thought on this current reality in Haiti?

The day I would think that I can use the Haitian people, the Haitian people would start to distance themselves from me and deny me. They would be right to do that, because no one, as a politician, should pretend the people are dumb enough to be used for votes, for instance. I did my best to respect the Haitian people and I will continue to do my best to show respect for them and for their wishes. In 1990, when I was elected president, people were working in sweatshops for nine cents an hour. When I managed to raise the minimum wage it was enough to have a coup. And it happened in Honduras last year because part of the game was this: don’t raise the minimum wage, so people must work as slaves.

Today, the Haitian people remember what together we were trying to do. We were not just using them for votes. They are not dumb: we were moving together through democratic principles for a better life. If now they continue to ask for my return six years after my kidnapping that means they are very bright. They may be illiterate, but they are not dumb. They remember what together we were trying to do. So I wish that the politicians would not focus on me, but rather on the people and not the people for elections but for their rights – the right to eat, the right to go to school, the right for healthcare, and the right to participate in a government. Unfortunately, in 2006 they elected someone who betrayed them, so they realize that now. Wow. They say: Who else will come? Will that person betray us after getting our votes? They are hesitating, and I understand them because they are not dumb.

Now here is a practical question. How do you want to deal with the Lavalas party in Haiti? You are still the national leader of Lavalas. Don’t you think that it would be a better idea to transfer the leadership to someone in Haiti? Would that not be a better long-term strategy, rather than hanging on to the title of party leader? After all, that's one of the pretexts used to not allow Lavalas to participate in the past elections and the future of Haiti as well?

If we respect the will of the people, then we must pay attention to what they are saying. I am here, but they are making the decisions. If today they decide they have to go that way, then you have to respect their will. That means I am not the one preventing them from moving on with a congress and having another leader and so on. As a matter of fact I am not acting as national leader outside of Haiti, not at all. I don’t pretend to be able to do that and I don’t want to do that. I know it would not be good for the people to do something like that.

They have said that it is a question of principle. First, they want my return, and then they can organize a congress to elect a new leader and move ahead. I respect that. If today they want to change it, I will their will. That is democracy.

What is behind the national picture is a logical fallacy. It’s a logical fallacy when, for instance, they pretend they have to exclude Lavalas to solve the problem. To not have Lavalas in an election, because it's a selection, it’s a logical fallacy.

Before I said ”Post hoc ergo propter hoc” or “after this, therefore because of this” and now I can say “Cum hoc, ergo propter hoc,” - “With this therefore because of this.” It’s a logical fallacy as well. They would not solve the problem without the majority of the people. They have to include them in a free and fair democratic election with my return or before my return or after my return. The inclusion of the people is indispensable to be logical and to move towards a better Haiti. That’s the solution.

So practically, if you were to say today that you would endorse Maryse Narcisse as the national leader they would accept Lavalas candidates?

Last year I received a letter from the Provisional Electoral Council, by the way, a council that was selected by the president, which is why they do what he wants. Excluding Lavalas was the implementation of the will of the government of Haiti.

I received a letter from them inviting me to a meeting and I said to myself, “Oh that is good. I am ready. I will go.” Then they said in the letter, “If you cannot come, will you send someone on your behalf?” So I said okay and I replied in a letter (1), which became public, asking Dr. Maryse Narcisse to represent Lavalas and to present the candidates of Lavalas based on the letter I received from the CEP. But they denied it because the game was to send the letter to me and assume that I would not answer. Then they could tell the Haitian people, “Look he does not want to participate in the election.” So they were using a pretext to pretend that they are intelligent, but in reality to hide the truth.

Did they not claim it was false at some point, or that it was not your signature?

They claimed that the mandate from me should have been validated by the Haitian consulate in South Africa, when they know that there is no representative of the Haitian government in South Africa, you see.

No embassy at all.

No. When I was President, I had named an Ambassador to South Africa, but that ended with the coup. After our independence, we had to wait until 1990 to have free democratic elections. We cannot change the economic reality in one day, in one year, but at least we should continue to respect the right of Haitians to vote. So today, why play with the right to vote? It’s cynical. You cannot improve their economic life and you deny them their right to vote. It’s cynical. South Africa did something which could be good for many countries, including Haiti. In 1994, when South Africans could vote, they voted. They are trying to move from free and fair elections while trying to improve their economic life. This is the right way to go. Not denying the right for poor people to vote while you cannot even improve their life.

The night of the coup. You spoke about it already and at the time you said to me that you were writing a book about it. Is that still in the works?

The book has been finished since 2004.

Ready to be published?

It was ready to be published and it would be published if I were allowed to do that.

Do you still remember the night of the coup - and I am sure you do because nobody is used to being awakened in the middle of the night and sent on a plane surrounded by armed people. Do you wish you had said no to Mr. Moreno, “I am not signing this letter of resignation” or “I won’t get on that plane. I will deal with the security issues in Haiti with my government”?

As I just said, if I were allowed to publish the book, the book would have been published in 2004. So in the book, you have the answers to your important questions and that is why now I will not elaborate on it, based on what I just said. In one word, I would do exactly what I did and I would say exactly why I said because it was right what I said and what I did. They were wrong, and they are still wrong.

What is known is the letter (2) in Kreyol that you signed and was according to you mistranslated.

Of course it was mistranslated.

Right, but you also you clearly stated that you were forced at gunpoint and that’s public knowledge.

It is, but if I don’t elaborate, it’s not because I want to give an evasive answer. It’s just based on what I said to you before.

What if the book never gets published?

Maybe it’s the same reason why I am still here (laughs). I wish they let me leave as well as let the book get published (laughs).

There have been these accusations (3) of corruption against you starting with filmmaker Raoul Peck and then taken over by Ms. Lucy Komisar and Ms. Mary Anastasia O’Grady of the Wall Street Journal about your personal involvement in a Teleco/IDT deal back in 2003. Can you put these accusations to rest?

First, they are lying. Second, what can we expect from a mental slave? (laughs) He will lie for his masters. He is paid to lie for his masters, so I am not surprised by these nonsensical allegations. As I said, they are lying.

They are lying. But it’s possible that maybe under you at some level in your government there was some corruption involving Teleco and IDT?

I never heard about things like that when I was there and I never knew about it. If I had known, of course we would have done our best to stop it or to prevent it or to legally punish those who could have been involved in such a thing.

Why have you not declared this publicly? Because these things happen all the time. I am sure there is corruption at every level in the South African government as there is under the Obama Administration. Things happen and we don’t need to examine Haiti only to find it. You could say that you were the head of state but not the head of Teleco. Things happen.

As I said, there are more people receiving money to lie than people receiving money to tell the truth. I don’t know how many times I have answered this question, but sometimes the journalist may have the answer but is not allowed to make it public. (laughs).

Would you be in favor of creating a Haitian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, similar to what South Africa did, that would allow some of the people who have been exiled under Duvalier and Cedras and your two presidencies to come back and be called to appear in that commission - and ask for forgiveness and amnesty if needed?

What I will say now, is not because I am now outside Haiti wanting to go back that I will say it. No, I already said it and I will just repeat it: There is no way to move forward in Haiti without dialogue. Dialogue among Haitians. Once we had an army of 7,000 soldiers controlling 40% of the national budget, but moving from coup d’état to coup d’état. I said no. Let’s disband the army, let’s have a police force to protect the right of every citizen, let’s have dialogue to address our differences. There is no democracy without opposition.

We have to understand one another when we oppose each other. We are not enemies, so we have to address our differences in a democratic way and only then can we move ahead. I have said it so many times already. We still have people calling themselves friends of Haiti coming to exploit the resources. They don’t want national dialogue. They don’t want Haitians to live peacefully with Haitians.

South Africa did it when they had The Commission of Truth and Reconciliation. People came and realized that they had made mistakes. Everybody can make mistakes. You must acknowledge that you made mistakes, and the society will welcome you. If you cannot do that through tribunals because of the numbers, then find a way to address it. We cannot pretend that Haiti will have a better future without that dialogue. We must have it.

In 1994, when I went back to Haiti from exile, we established a Commission for Truth and Justice and Reconciliation. I passed the documents to the next government, and I never heard about it again. Haitians never heard about it because the government wanted to move fast towards privatization of state enterprises instead of that path which was recommended.

Would that mean allowing all the political exiles to come back no matter how bad they were, including people like Raoul Cedras and Jean-Claude Duvalier.

I will not move forward with conclusions outside of that framework of justice. The Commission addressed the case of these criminals and paved the way for justice and dialogue. You see, so I said it and will continue to say it: We need to continue to address this issue of dialogue, truth and justice. Otherwise, we will continue to play either like a puppet government or be mental slaves in the hands of those who still want to exploit our resources and they will not decide to change it for Haitians. Haitians must start to say no. Let’s change it – not against foreigners, not against true friends, with them if they want, but they will not do it for us unless we start to do it.

Do you hold a grudge today against president René Préval for not being more forceful in trying to facilitate your return to Haiti? He owes his election thanks to the Lavalas base.

If I pay attention to what the people are saying, they describe President Préval as someone who betrayed me and it's true. They voted for him. I did not vote, I was here, but those who elected him now realize he has failed them. He betrayed them.

He is playing in the hands of those who are against the interests of the people – that is what they said.

Do you feel personally betrayed? I am sure you realize the difficulties of the situation he was in.

Personally, I say let’s put the interests of the people first. Not my interests. If I can do something for him, or if I have to, I will do it. It’s a matter of principle an in his case he did not have to do anything for me. He just had to respect the constitution. The constitution does not allow exile. He should not violate the constitution. That is it. But as he did, history takes note and history will recognize that he failed, unfortunately.

I remember a famous progressive journalist in Geneva reviewing my film (4) and one of the critics he had was that I did not speak about voodoo and how it affects Haiti’s politics. What do you think of this tendency among many western journalists who try to explain Voodoo as one main reason for Haiti’s problems?

I enjoy drawing parallels between voodoo and politics. Why? Because in the west when they want to address political issues, they may, as you suggested or indicated, mix it with voodoo as a way to avoid going straight to the truth. The truth could be, for instance, historical.

Fourteen years after Christopher Columbus arrived in Haiti, in 1492, they had already killed three million indigenous people. Do they speak about it today? Do they know about it? I don’t know. At that time, one could be 14 years old and would have to pay a quarter of gold to Christopher Columbus or they would cut your arm or feet or ears. Do they talk about it? If you do, it’s like “oh really or maybe.” They have problems exposing the truth, acknowledging what was going on at that time. And if you look at the reality of today, it is almost the same thing.

Last week there was some trouble because of storms and earthquakes and Haiti lost about ten people, some say five some say more than ten. In any case, even if it were one person, it would already mean a lot for us because a human being is human being. Instead of focusing on what is the reality of misery, abject poverty, occupation, colonization, some prefer to find a scapegoat through voodoo. The UN itself had to expel 114 soldiers for rape and child abuse. So we see people invading a country, pretending to help, while they are actually involved in rape, child abuse and so on. And it is not an issue for people who like to talk about voodoo as if voodoo by itself could cover this reality. The same way they don’t want to face our historical drama linked to colonization.

Is it a racist distraction?

It is, it is. I respect religion and will respect any religion. Africans had their religion here. They went to Haiti and continued their practice and I have to respect that. In addition, the Haitian constitution, respects freedom of religion. So let’s address the drama, misery, poverty, exploitation, occupation, and people without the right to vote or eat. People want to be free. They don’t have self-determination. Let’s focus on people who have no resources and are dying. We had such a wonderful solidarity after January 12 in the world, where citizens worldwide were building solidarity with Haitians. That was great to see Whites and Blacks crossing barriers of color to express their solidarity with the victims of the deadly earthquake.

And on behalf of the Haitian people, if I may, I will say thank you to all those true friends who did it while others who call themselves true friends of Haiti preferred to send soldiers with weapons to protect their own interests instead of protecting human beings who were really suffering. Amputations – we had them by the thousands without anesthesia. They were cutting hands and feet of victims and it’s not an issue for some people who prefer to talk about voodoo as if voodoo could be the cause of what is going on in Haiti. No, what is going on in Haiti is rooted in colonialism, neo-colonialism in that neoliberal policy applied and imposed upon Haiti, not in religious issues like voodoo. For me, as long as they don’t try to face the reality as it is, they may continue to use issues like voodoo to hide facts, any attempt to replace truth by racist distractions will fail.

Anything that you would like to add that you have at heart and have not been able to tell?

Well … if you ask a Zulu* person the way to reach somewhere while you are on the right path, that person will tell you (in Zulu): “Ugonde ngqo ngalo mgwago” which means go straight on your way.

That is why the Haitian people who are moving from misery to poverty with dignity should continue to move straight towards that goal. If we lose our dignity we lose everything. We are poor – worse than poor because we are living in abject poverty and misery. But based on that collective dignity rooted in our forefathers, I do believe we have to continue fighting in a peaceful way for our self-determination, and if we do that, history will pay tribute to our generation, because we are on the right path.

Mr. President, thank you for your time.

*****************

Footnotes:

[*] Lavalas is a Creole word meaning ‘flood’, ‘avalanche’, a ‘mass of people’ or ‘everyone together’. Fanmi means ‘family’. [*] Zulu is the name of the largest ethnic group in South Africa and the most widely spoken home language as well.

(1) Letter of President Aristide - November 2009 - authorizing Dr. Maryse Narcisse to register Lavalas candidates. http://www.hayti.net/tribune/index.php?mod=articles&ac=commentaires&id=725

(2) Letters of resignation of Jean-Bertrand Aristide - The Kreyol translation by professor Bryant Freeman, http://www.nathanielturner.com/aristidedidnotresign.htm - The official translation provided by the US embassy and used most widely in mainstream medias, http://articles.cnn.com/2004-03-01/world/aristide.letter_1_constitution-...

(3) “Aristide’s American Profiteers”, an article by Mary Anastasia O’Grady, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121720095066688387.html

(4) “Aristide and the Endless Revolution”, a documentary by Nicolas Rossier, http://www.aristidethefilm.com

Nicolas Rossier is an award winning independent filmmaker and reporter who lives in Brooklyn New York. In 2005, he directed and produced the outstanding 85-minute documentart, "Aristide and the Endless Revolution." For copyright information and publishing rights, please contact the author at Nicrossier@gmail.com.

Ward at St. Nicholas Hospital

Ward at St. Nicholas Hospital

Cubans in Solidarity with Haitians

Cubans in Solidarity with Haitians

An exhausted Dr. Iliuska Sanchez of the Cuban Brigade

An exhausted Dr. Iliuska Sanchez of the Cuban Brigade