UPDATE:

911 Calls Released

In Trayvon Martin Case

__________________________Witness Speaks Out

In Trayvon Martin Case

__________________________

The Curious Case of Trayvon Martin

By CHARLES M. BLOW

Published: March 16, 2012

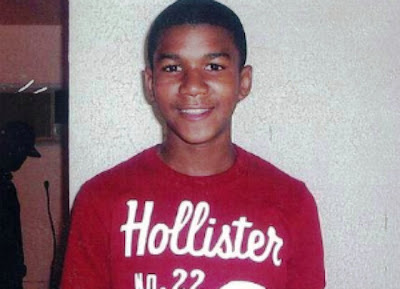

“He said that Tray was gone.”

That’s how Sybrina Fulton, her voice full of ache, told me she found out that her 17-year-old son, Trayvon Martin, had died. In a wrenching telephone call, the boy’s father, who had taken him to visit a friend, told her that Trayvon had been gunned down in a gated townhouse community in Sanford, Fla., outside Orlando.“He said, ‘Somebody shot Trayvon and killed him.’ And I was like, ‘Are you sure?’ ” Fulton continued in disbelief. “I said ‘How do you know that’s Trayvon?’ And he said because they showed him a picture.”

That was Feb. 27, one day after Trayvon was shot. The father thought that he was missing, according to the family’s lawyer, Benjamin Crump, but the boy’s body had actually been taken to the medical examiner’s office and listed as a John Doe.

The father called the Missing Persons Unit. No luck. Then he called 911. The police asked the father to describe the boy, after which they sent officers to the house where the father was staying. There they showed him a picture of the boy with blood coming out of his mouth.

This is a nightmare scenario for any parent, and the events leading to Trayvon’s death offer little comfort — and pose many questions.

Trayvon had left the house he and his father were visiting to walk to the local 7-Eleven. On his way back, he caught the attention of George Zimmerman, a 28-year-old neighborhood watch captain, who was in a sport-utility vehicle. Zimmerman called the police because the boy looked “real suspicious,” according to a 911 call released late Friday. The operator told Zimmerman that officers were being dispatched and not to pursue the boy.

Zimmerman apparently pursued him anyway, at some point getting out of his car and confronting the boy. Trayvon had a bag of Skittles and a can of iced tea. Zimmerman had a 9 millimeter handgun.

The two allegedly engaged in a physical altercation. There was yelling, and then a gunshot.

When police arrived, Trayvon was face down in the grass with a fatal bullet wound to the chest. Zimmerman was standing with blood on his face and the back of his head and grass stains on his back, according to The Orlando Sentinel.

Trayvon’s lifeless body was taken away, tagged and held. Zimmerman was taken into custody, questioned and released. Zimmerman said he was the one yelling for help. He said that he acted in self-defense. The police say that they have found no evidence to dispute Zimmerman’s claim.

One other point: Trayvon is black. Zimmerman is not.

Trayvon was buried on March 3. Zimmerman is still free and has not been arrested or charged with a crime.

Yet the questions remain: Why did Zimmerman find Trayvon suspicious? Why did he pursue the boy when the 911 operator instructed him not to? Why did he get out of the car, and why did he take his gun when he did? How is it self-defense when you are the one in pursuit? Who initiated the altercation? Who cried for help? Did Trayvon’s body show evidence of a struggle? What moved Zimmerman to use lethal force?

This case has reignited a furor about vigilante justice, racial-profiling and equitable treatment under the law, and it has stirred the pot of racial strife.

As the father of two black teenage boys, this case hits close to home. This is the fear that seizes me whenever my boys are out in the world: that a man with a gun and an itchy finger will find them “suspicious.” That passions may run hot and blood run cold. That it might all end with a hole in their chest and hole in my heart. That the law might prove insufficient to salve my loss.

That is the burden of black boys in America and the people that love them: running the risk of being descended upon in the dark and caught in the cross-hairs of someone who crosses the line.

The racial sensitivity of this case is heavy. Trayvon’s parents have said their son was murdered. Crump, the family’s lawyer, told me, “You know, if Trayvon would have been the triggerman, it’s nothing Trayvon Martin could have said to keep police from arresting him Day 1, Hour 1.” Even the police chief recognizes this reality, even while disputing claims of racial bias in the investigation: “Our investigation is color blind and based on the facts and circumstances, not color. I know I can say that until I am blue in the face, but, as a white man in a uniform, I know it doesn’t mean anything to anybody.”

Zimmerman has not released a statement, but his father delivered a one-page letter to The Orlando Sentinel on Thursday. According to the newspaper, the statement said that Zimmerman is “Hispanic and grew up in a multiracial family.” The paper quotes the letter as reading, “He would be the last to discriminate for any reason whatsoever” and continues, “The media portrayal of George as a racist could not be further from the truth.” And disclosures made since the shooting complicate people’s perception of fairness in the case.

According to Crump, the father was told that one of the reasons Zimmerman wasn’t arrested was because he had a “squeaky clean” record. It wasn’t. According to the local news station WFTV, Zimmerman was arrested in 2005 for “battery on a law enforcement officer.”

Furthermore, ABC News reported on Tuesday that one of the responding officers “corrected a witness after she told him that she heard the teen cry for help.” And The Miami Herald published an article on Thursday that said three witnesses had heard the “desperate wail of a child, a gunshot, and then silence.”

WFTV also reported this week that the officer in charge of the scene when Trayvon was shot was also in charge of another controversial case. In 2010, a lieutenant’s son was videotaped attacking a black homeless man. The officer’s son also was not initially arrested in that case. He was later arrested when the television station broke the news.

Although we must wait to get the results from all the investigations into Trayvon’s killing, it is clear that it is a tragedy. If no wrongdoing of any sort is ascribed to the incident, it will be an even greater tragedy.

One of the witnesses was a 13-year-old black boy who recorded a video for The Orlando Sentinel recounting what he saw. The boy is wearing a striped polo shirt, holding a microphone, speaking low and deliberately and has the heavy look of worry and sadness in his eyes. He describes hearing screaming, seeing someone on the ground and hearing gunshots. The video ends with the boy saying, “I just think that sometimes people get stereotyped, and I fit into the stereotype as the person who got shot.”

And that is the burden of black boys, and this case can either ease or exacerbate it.

__________________________

Sorry, Trayvon Martin:

They Just Don't Like You

(UPDATED)

"It is about time the court faced the fact that the white people of the South don't like the colored people." -- Chief Justice William Rehnquist (written when he was a law clerk on the Supreme Court). The recent murder of Trayvon Martin, a black teenager, by George Zimmerman, a white "neighborhood watch vigilante from Sanford, Florida, should remind the public of the continuation of racial injustice in the United States. Zimmerman shot and killed Martin as he walked to his father's home in a central Florida neighborhood. Prior to shooting Martin, Zimmerman called police from his car to report a "suspicious" person in the neighborhood. Zimmerman asked police whether he should leave his car to investigate the situation, but police told him not to do so. Despite the police warning, Zimmerman left his car and confronted Martin. Although the facts remain hazy, Zimmerman admits that after he left his car, he killed Martin. Zimmerman says that he acted in self-defense. Several witnesses tell local newspapers, however, that Zimmerman did not act in self-defense; they have also accused police of mishandlingthe investigation. It is also clear that Martin was unarmed and that he was returning to his father's home from a store where he had purchased candy for a younger sibling. Police have declined to arrest Zimmerman. Bill Lee, Chief of the Sanford Police Department, accepts Zimmerman's allegation that he acted in self-defense. Lee says that Zimmerman believed that Martin was a threat because "the way that he was walking or appeared seemed suspicious to him." Lee also says (mistakenly - see below) that Zimmerman has a "squeaky clean" record and that he does not believe that "it was [Zimmerman's] intent to go and shoot somebody. . . .” Currently, prosecutors are considering whether to bring criminal charges against Zimmerman. This case is deeply troubling for several reasons. First, the police are misapplying and misleading the public about the criminal laws regarding homicide and self-defense in order to justify the decision not to arrest Zimmerman. Also, this case is yet another reminder of the continuing problem of racial injustice in the United States, particularly, the disparate treatment of black and white offenders and victims. Law Regarding Homicide and Self-Defense The law regarding homicide is far more complicated than the public's general understanding of the term. While the public tends to equate "homicide" and "murder," these words are quite different from a legal perspective. Homicide is simply the killing of a person by another individual. Within that broad category, however, several scenarios are possible. The killing could result from intentional and planned behavior; this is typically described as "murder." The killing could result from recklessness or negligence; this is typically described as "manslaughter." Although I have simplified these categories somewhat, it is clear that even if Zimmerman did not begin the night with the intent to kill an individual, he still might have committed a serious crime -- possibly, manslaughter or even second-degree murder. Every state recognizes "self-defense" as a defense to a homicide charge. Under Florida law (as in many other states), in order to act in self-defense, the assailant must reasonably fear that the victim will harm him or her or some other person. Furthermore, in order to rely upon self-defense, the assailant must not have acted act as the aggressor. In order to act with lethal force, as Zimmerman did, the assailant must reasonably fear that the victim will cause imminent great bodily harm or death to him or her or to another person. Under Florida law, lethal force is also justifiable to stop home invasions and carjacking -- scenarios that are not relevant to Martin's death. The Facts Support Charging Zimmerman From the few facts that are known, Zimmerman's self-defense claim seems shaky at best. Zimmerman, who is 26, weighs about 100 pounds more than Martin, who was 17. Zimmerman was safe in his car and advised by police to remain inside. Zimmerman admitted to following Martin in his car. Zimmerman was armed with a gun. Martin was unarmed. The facts of the case do not suggest that Zimmerman was justified in using deadly force against Martin. Instead, they suggest the opposite: Martin should have feared Zimmerman. Martin should have feared Zimmerman because Zimmerman was following -- or stalking -- him in a vehicle. Zimmerman left the car to confront Martin. Zimmerman was much larger than Martin. Zimmerman was armed with a deadly weapon. Zimmerman was likely the aggressor because he left his car and confronted Martin. Under these circumstances, if Martin fought Zimmerman, he likely had the right to do so according to Florida law regarding self-defense. Zimmerman's behavior would cause a reasonable person to fear him. Furthermore, the police statement that Zimmerman has a squeaky clean record is not exactly true. In 2005 Zimmerman was charged withresisting arrest with violence and battery upon a police officer. Also, residents in Zimmerman's neighborhood allegedly complained to police about his aggressive tactics in the past. Even though these additional factors could not prove guilt in a court of law (and might not even be admissible as evidence), they certainly are the type of information police routinely use before making arrests.

Racism Still Exists

The oldest "race card" is the denial that racism exists. Despite the popular belief that the United States is post-racial, racism remains a substantial factor in American culture. Indeed, this case follows a disturbing racial pattern that was typical during Jim Crow and segregation. The police have discounted the value of the black victim. The police have accepted as factual the allegations of the white assailant -- however suspicious they sound. The police have failed to charge a white man who unlawfully killed an innocent black male. And the police have stated that the black victim was the aggressor. These traditional patterns of racism that exist in the Martin case were pervasive during Jim Crow. These racist patterns also exist far beyond the Martin case. Social scientists continue to conduct studies that reveal implicit racial bias in the United States. Even people who consider themselves racial egalitarians often act upon stereotypical beliefs about persons of color. In one study, researchers showed a series of images of individuals to test subjects. The participants were told to "shoot" at images that also included a gun. More often, test subjects incorrectly shot unarmed black subjects; they paused, however, before shooting white subjects, which limited the amount of incorrect outcomes. The researchers repeated this study with police officers and found frighteningly similar results: race impacted the subjects' conclusion that the image was armed. This same instinctive racial thinking could have impacted Zimmerman. Others studies demonstrate that whites are more sympathetic crime victims than blacks and Latinos. This pattern even impacts reports of crime in the media. Compare, for example, the extreme level of media attention to white female crime victims (in particular) with the reaction to black victims, including Martin. If Martin were killed in Aruba, like Natalee Holloway, he still would not receive the same volume of attention her death attracted from the media. Race and gender biases explain this differential treatment. And, to reiterate, these biases even affect the behavior of individuals who sincerely describe themselves as nonracist, which is how Zimmerman's father recently portrayed his son.

What To Do Next Currently, prosecutors are examining Martin's death. Because prosecutors are elected and impacted by social biases, however, it is unclear whether they will behave differently than the police. In order to provide justice in this case, a new investigation should take place with different investigators. The Sanford police department lacks credibility. Also, Chief Lee needs to lose his job. He is shielding a likely violent felon, rather than helping the victim. This is atrocious behavior. Finally, the public needs to admit that race still remains a powerful force in the United States. Researchers who have documented the existence of implicit bias have also found that training and education can prevent racist behavior. Unless the public admits that racism remains a substantial social issue, then people will not recognize the need for training and education. The greatest outcome of young Trayvon's death could be progress towards a more just society. UPDATE: Apparently, the Sanford police department has issues. See BREAKING NEWS in Trayvon Martin Case: Officer in the Case Has A Prior Record of Racial Controversy. Note: Police have released the 911 tapes. The tape of Zimmerman's call contradicts police accounts of the Martin's killing.

- Darren Lenard Hutchinson

- Washington, DC, United States

- Professor Darren Hutchinson teaches Constitutional Law, Critical Race Theory, Law and Social Change, and Equal Protection Theory at the American University, Washington College of Law. Professor Hutchinson received a B.A., cum laude, from the University of Pennsylvania and a J.D. from Yale Law School.

- __________________________

"Justifiable Homicides"

Are on the Rise:

Have Self-Defense Laws

Gone Too Far?

One year ago today, a 61-year old Texan named Joe Horn looked out his window in Pasadena, just outside of Houston, and saw a pair of black men on his neighbor's property. It appeared to be a burglary in action, so he called 911. But as he described what he saw to the emergency dispatcher, he began to get agitated. The police would take too long to get there, he decided. Instead, he'd stop the crime himself. "I've got a shotgun," Horn told the 911 dispatcher. "You want me to stop him?" The dispatcher tried to talk him down. "Nope, don't do that," he told Horn. "Ain't no property worth shooting somebody over, OK?" It was not OK with Horn. With the dispatcher still on the phone, he grabbed his gun, went outside, yelled, "Move, you're dead!" -- and shot the two men in the back. The victims turned out to be two undocumented immigrants from Colombia, Diego Ortiz and Miguel de Jesus. Both died on the scene. The killings sparked instant controversy nationwide, with some labeling it a deplorable act of vigilante justice, and others calling Horn a hero for defending his neighbor's property. Because the victims were in the country illegally, the controversy was further fueled by the ugly, ongoing fight over immigration. Protesters who arrived on Horn's block to call for justice for his victims were met with counterprotesters waving signs in support of their neighbor. "Once again, our chaotic immigration system has led to death," Bill O'Reilly fumed on Dec. 6, 2007. This summer, Horn was officially cleared of wrongdoing, when a grand jury failed to indict him on any charges. The decision was met with dismay by the families of Ortiz and de Jesus. Diamond Morgan, Ortiz's widow, will now raise their infant son without him. "It's horrible," she said about the 911 recording. "(Horn) was so eager, so eager to shoot." "This man took the law into his own hands," Stephanie Storey, de Jesus' fiancee, told reporters. "He shot two individuals in the back after having been told over and over to stay inside. It was his choice to go outside and his choice to take two lives." But Horn and his attorney claimed that in addition to protecting his neighbor's home, he was acting in self-defense. "He was afraid for his life," his lawyer, Tom Lambright argued. " … I don't think Joe had time to make a conscious decision. I think he only had time to react to what was going on. Short answer is, he was defending his life. " But the 9/11 recording tells a different story:

Horn: He's coming out the window right now, I gotta go, buddy. I'm sorry, but he's coming out the window.

Dispatcher: Don't, don't -- don't go out the door. Mr. Horn? Mr. Horn?

Horn: They just stole something. I'm going after them, I'm sorry.

Dispatcher: Don't go outside.

Horn: I ain't letting them get away with this shit. They stole something. They got a bag of something.

Dispatcher: Don't go outside the house.

Horn: I'm doing this.

Dispatcher: Mr. Horn, do not go outside the house.

Horn: I'm sorry. This ain't right, buddy.

Dispatcher: You're going to get yourself shot if you go outside that house with a gun, I don't care what you think.

Horn: You want to make a bet?

Dispatcher: OK? Stay in the house.

Horn: They're getting away!

Dispatcher: That's all right. Property's not worth killing someone over, OK?

Horn: (curses)

Dispatcher: Don't go out the house. Don't be shooting nobody. I know you're pissed and you're frustrated, but don't do it.

Horn: They got a bag of loot.

Dispatcher: OK. How big is the bag? … Which way are they going?

Horn: I'm going outside. I'll find out.

Dispatcher: I don't want you going outside, Mr. Horn.

Horn: Well, here it goes, buddy. You hear the shotgun clicking and I'm going.

Dispatcher: Don't go outside.

Horn: (yelling) Move, you're dead!

(Sound of shots being fired)

Besides being a disturbing recording, the tape is also notable for what it reveals about the moments before Horn saw Ortiz and de Jesus emerge from the window. "I have a right to protect myself too, sir," Horn argued with the dispatcher. "… And the laws have been changed in this country since September the first, and you know it and I know it." Horn was referring to Texas's newly enacted Castle Law, signed by Gov. Rick Perry on March 27, 2007, and which had gone into effect that fall. The law, as described by the governor, "allows Texans to not only protect themselves from criminals, but to receive the protection of state law when circumstances dictate that they use deadly force." Its benefit, Perry said, is that "it protects law-abiding citizens from unfair litigation and further clarifies their right to self-defense." It may seem like a stretch to say Horn was acting out of self-defense. As CNN legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin observed after listening to the tape, "He does not appear to be someone who's in a panic. It's a very cool and rather chilling determination to go out and use his gun, against the instructions of the 911 operator." Nevertheless, the new statute ultimately saved Horn from prosecution. Whether or not the law was designed to protect private property as much as human life, rather than "clarifying" the right to self-defense, as Perry claims, the practical effect of Texas' Castle Law appears to be a broadening of the definition to an unprecedented -- and deadly -- degree. "Stand Your Ground" Laws The Castle Law is not some wild Texas invention. In fact, the "castle doctrine" is a concept that dates back to English Common Law. As Ohio State law professor and criminal justice expert Joshua Dressler explains, the castle doctrine basically dictates "that your home is your castle; it's the one place where you should be able to be free from intrusion." This idea has provided the legal basis for self-defense legislation across the country for years -- legislation that traditionally has also acknowledged a person's "duty to retreat" in the face of a threatening situation. "The law has always taken the view for self-defense that someone can use deadly force to respond to what the person reasonably believes is a threat," explains Dressler. But, he adds, "the old law tended to be that people ought not to use deadly force until absolutely necessary. They tended to require people to find non-deadly solutions." Recent decades have seen some exceptions. One precursor to the new Texas law is a 1985 Colorado law, nicknamed the "Make My Day" law, that treats property crimes as legitimate grounds for the use of force. The law came under national scrutiny in 1990, when an 18-year-old named Laureano Jacobo Grieigo Jr. was shot in the head by a 69-year-old-man as he fled his the man's home in an unsuccessful robbery attempt. No charges were filed, and an article published in the New York Times at the time called the law an "unusual" statute "that protects people from any criminal charge or civil suit if they use force -- including deadly force -- against an invader of the home." (The same article quoted a criminologist at Florida International University, Dr. William Wilbanks, who warned that the law was ripe for abuse. "The danger is not that this kind of law will be abandoned, but that it will be extended even more," he said. ''The public sentiment is clearly behind this kind of law.") Almost two decades later, Texas' Castle Law is part of a wave of similar legislation passed by states throughout the country, building upon the castle doctrine and broadening the right of civilians to use lethal force under the auspices of self-defense. The new laws are particularly expansive in that they go beyond the boundaries of private homes to include cars, workplaces or anywhere else a person may feel threatened. In this sense, says Dressler, "what is happening is that the castle doctrine is becoming less important." Leading the pack was Florida. In 2005, Gov. Jeb Bush signed a law that, as written, "authorizes (a) person to use force, including deadly force, against (an) intruder or attacker in (a) dwelling, residence, or vehicle under specified circumstances." The law "provides that person is justified in using deadly force under certain circumstances," and "provides immunity from criminal prosecution or civil action for using deadly force." Formally called the "Protection of Persons/Use of Force" law, it became known as the "Stand Your Ground" law. Heavily backed by the National Rifle Association, Florida's new law alarmed more than just gun control advocates. Many people were appalled at the fact that it could apply in public spaces. As the Christian Science Monitor reported at the time:

"Most significantly, (the law) now extends that right to public places, too, meaning that a person no longer has a duty to retreat from what they perceive to be a threatening situation before they are entitled to pull the trigger. Members of the public may now stand their ground and "meet force with force," it states, without fear of criminal prosecution or civil litigation. "It's common sense to allow people to defend themselves," said Gov. Jeb Bush (R) as he signed the new law."

Only 20 state legislators opposed the law. One Democratic critic worried that it could "turn Florida into the OK Corral," but other Democratic politicians "admitted that they did not want to appear soft on crime by voting against it." It helped that one of the driving forces behind the law was Marion Hammer, a lobbyist who argued that the law would protect women against abuse and assault. She "characterized herself as a feminist," recalls Dressler, "but … more relevantly, was a former president of the NRA." Mere months after the passage of Florida's "Stand Your Ground" law, similar legislation was being proposed in more than 20 states. The NRA was happy to take the credit. "Today, the NRA is feeding the firebox of Castle Doctrine legislation in states throughout the country," an article posted on the NRA's Institute for Legislative Action Web site boasted, crediting itself with "reuniting Americans with the right to protect themselves and loved ones from danger." "Justifiable Homicides" on the Rise Today, there are similar new laws in at least 15 states across the country, and while it may be too early to know the effects, in Texas, the newly passed Castle Law was followed by a series of shootings that prompted questioning over the potential "sudden impact." "Does new law make them quicker to pull the trigger?" asked the Dallas Morning News in January. (At least one source said yes: "I think the Castle Law has more citizens thinking about fighting back, knowing they're protected from being sued later," said a Dallas man who shot and killed a man who broke into his garage, "where he stored thousands of dollars worth of tools.") Anecdotal evidence aside, one recent government report suggests that the laws may be having some effect. A little-noticed study released in mid-October by the FBI found a spike in the number of "justifiable homicides" recorded in the past few years. The FBI defines "justifiable homicides" as "certain willful killings" that "must be reported as justifiable, or excusable." This includes "the killing of a felon by a peace officer in the line of duty" and "the killing of a felon, during the commission of a felony, by a private citizen." According to the report, in 2007, police officers killed 391 people -- the highest number since 1994 -- and private citizens killed 254 -- the most since 1997. Although the report got little attention in the press, an article in USA Todayquoted criminal justice experts who cited "an emerging 'shoot-first' mentality by police and private citizens" as a possible explanation. Dressler agrees. "What's been happening is that a lot of states have broadened their homicide rules to give greater authority to citizens to use deadly force in circumstances that in the past would not have been permissible," he says. Expanding "stand your ground" style legislation "means that there are going to be, in the future, many more homicides perpetrated by citizens against other citizens -- homicides that were in the past viewed as criminal now will be seen as justifiable." "If you talk to prosecutors, the message that they're getting is, really, don't even prosecute cases that come close to the category of what is now deemed 'just homicides.'" Whether a killing is "just" or not is currently determined by local police departments, to whom the concept is long familiar. "Police, of course, use justifiable homicide, both in self-defense and in crime prevention," explains Dressler, "but now a couple things are happening. One is the reality that … thanks to the NRA, some fairly conservative judges, Republicans, we've really become an armed nation. Far more people possess guns today than in the more distant past, and that means that when a police officer is dealing with someone, they have much greater reason to fear that the person they're dealing with is armed." This, perhaps, helps to explain the rise in "justifiable homicides" committed by police (not to mention the rise of "non-lethal" weapons like tasers, themselves deadly weapons). The recent FBI study is not the first time the government has tracked the number of "justifiable homicides" committed by police alongside those committed by civilians as if they were equivalent phenomena. But given that police officers are, at least in theory, trained to be uniquely authorized to use force in a law enforcement capacity, to what extent do these new laws blur the distinction between police and civilians? "I think the creed of the NRA is that citizens/civilians have the right to use deadly force because the police don't (or cannot) protect us," says Dressler. "So, under that view, yes, the distinction is blurring." More Homicides Will Be Seen as Justifiable Although it may be an old concept, the notion of "justifiable homicides" is itself a slippery one. Anti-abortion extremists, for example, have used the term to describe the killing of abortion providers, on the grounds that they are defending the lives of the unborn. But perhaps more alarming is the positive connotation the term holds for some. When a Memphis paper reported earlier this year that the number of local justifiable homicides "jumped from 11 in 2006 to 32 in 2007," it quoted a firearms instructor whose (admittedly unscientific) explanation was that "the thugs have started running into people who can protect themselves." It's a rather glib way to talk about murder, and the perverse effect is to cast the killings as a positive trend. In Memphis that year, the 32 "justifiable homicides" included four killings by police officers. "All were found to be what internal affairs investigators term 'good shoots,'" according to the report, which explained that "Tennessee law gives citizens the right to defend themselves if they have a reasonable and imminent fear of harm from a carjacker, rapist, burglar or other violent assailant. They can also employ deadly force to protect another person." But what about another person's property, as in the case of Joe Horn? If a person can shoot two men in the back and get away with it -- and, indeed, if he cites his legal right to do so -- haven't these laws gone too far? Dressler thinks so. "My fear is that these changes in self-defense laws will lead to a lot more homicides -- and that a lot more homicides will be seen as justifiable."