It's Fat Tuesday!

Commentary by Black Kos Editor Denise Oliver Velez

Today is Mardi Gras, or Fat Tuesday, or Carnival—the last day of celebration before people give up meat for Lent, and though the practice came from Europe it has now become a major part of African-diasporic tradition—from New Orleans, to Trinidad and of course Brazil, where the largest celebration in the world is held in Rio.

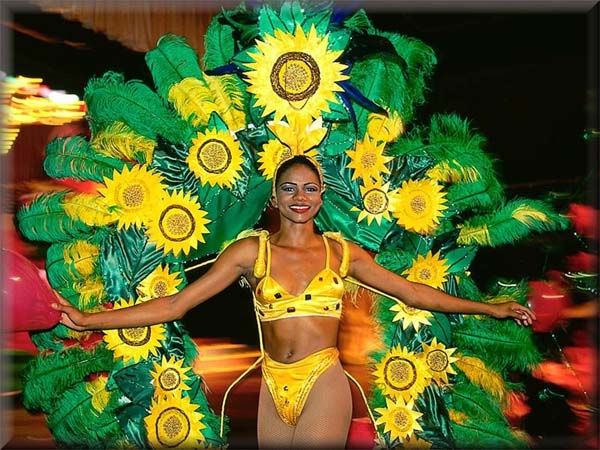

Many of the costumes in Brazil exhibit the nation's colors of green and gold.

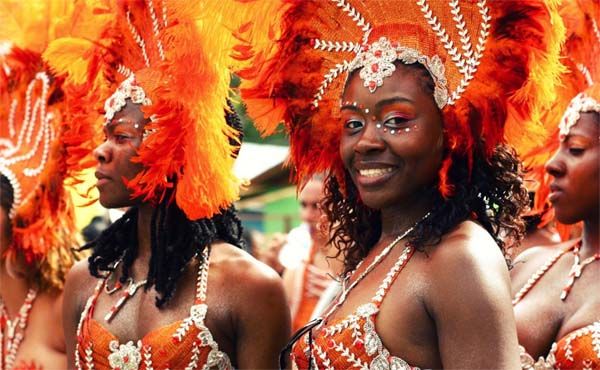

In Trinidad Carnival has a long history.

The French Revolution (1789) had an impact on Trinidad's culture, as it resulted in the emigration of Martinican planters and their French creole slaves to Trinidad where they established an agriculture-based economy (sugar and cocoa) for the island. Carnival had arrived with the French, indentured laborers and the slaves, who could not take part in Carnival, formed their own, parallel celebration called Canboulay. Canboulay (from the French cannes brulées, meaning burnt cane) is a precursor to Trinidad and Tobago Carnival, and had played an important role in the development of the music of Trinidad and Tobago. The festival is also where calypso music through chantwells had taken its roots. In 1797, Trinidad became a British crown colony, with a French-speaking population.Stick fighting and West African percussion music were banned in 1880, in response to the Canboulay Riots and British laws at the time. They were replaced by bamboo sticks beaten together, which were themselves banned in turn. In 1937 they reappeared, transformed as an orchestra of frying pans, dustbin lids and oil drums. These steelpans are now a major part of the Trinidadian music scene and are a popular section of the Canboulay music contests. In 1941, the United States Navy arrived on Trinidad, and the panmen, who were associated with lawlessness and violence, helped to popularize steel pan music among soldiers, which began its international popularization.

Carnival was created when West African slaves mimicked their French owners who where known for their lavish costumes balls. Forbidden to partake in these festivities and confined to their quarters, slaves combined elements from their own cultures to their master's fete. Hence the creation of characters such as Jab Jab or Jab Molassie (Devils), Midnight Robbers, Imps, Lagahroo, Soucouyant, La Diablesse and Demons. With the abolition of slavery in 1838, freed Africans took their version of Carnival to the streets through expression of drums, riddim sections like tamboo bamboo and as each new immigrant population entered Trinidad, Carnival evolved into what we know today.Trinidad is also famous for the Moko Jumbies.A moko jumbie (also known as "moko jumbi" or "mocko jumbie") is a stilts walker or dancer. The origin of the term may come from "Moko" (a possible reference to an African god) and "jumbi", a West Indian term for a ghost or spirit that may have been derived from the Kongo language word zumbi. The Moko Jumbies are thought to originate from West African tradition brought to the Caribbean.

Carnival was created when West African slaves mimicked their French owners who where known for their lavish costumes balls. Forbidden to partake in these festivities and confined to their quarters, slaves combined elements from their own cultures to their master's fete. Hence the creation of characters such as Jab Jab or Jab Molassie (Devils), Midnight Robbers, Imps, Lagahroo, Soucouyant, La Diablesse and Demons. With the abolition of slavery in 1838, freed Africans took their version of Carnival to the streets through expression of drums, riddim sections like tamboo bamboo and as each new immigrant population entered Trinidad, Carnival evolved into what we know today.Trinidad is also famous for the Moko Jumbies.A moko jumbie (also known as "moko jumbi" or "mocko jumbie") is a stilts walker or dancer. The origin of the term may come from "Moko" (a possible reference to an African god) and "jumbi", a West Indian term for a ghost or spirit that may have been derived from the Kongo language word zumbi. The Moko Jumbies are thought to originate from West African tradition brought to the Caribbean.

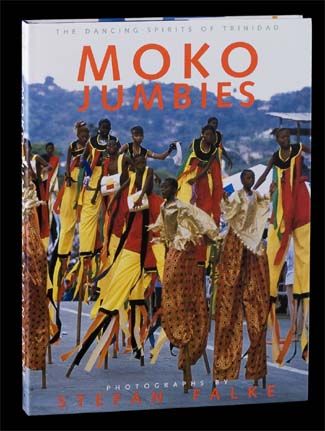

A book well worth purchasing is Moko Jumbies—The Dancing Spirits of Trinidad: A Photographic Essay of the Stilt-Walkers of Trinidad and Tobago, by Stefan Falke.

Seventeen years ago, Glen “Dragon” de Souza founded the Keylemanjahro School of Arts and Culture on the island of Trinidad. His mission was to revive the almost forgotten West African tradition of the Moko Jumbie or “stilt-walker,” and adopt it into the annual Carnival celebration. Today, more than one hundred Moko Jumbies—boys and girls starting from the age of four years old—practice at the Keylemanjahro School. Internationally recognized photographer Stefan Falke spent six years documenting these “dancing spirits” of Trinidad. With rare power, he captures the vivid costumes and haunting beauty of the Moko Jumbie dances in over 200 dazzling color photographs.Throughout the Caribbean, men and women dance and "whine" (or wine) in the streets.

If you are a bit dance challenged here's a simple "how to" video.

In Ponce, Puerto Rico during Carnival you will run into roving bands of vejigantes.

The vejigante is a folkloric figure who's origins trace back to medieval Spain. The legend goes that the vejigante represented the infidel Moors who were defeated in a battle led by Saint James. To honor the saint, the people dressed as demons took to the street in an annual procession. Over time, the vejigante became a kind of folkloric demon, but in Puerto Rico, it took on a new dimension with the introduction of African and native Taíno cultural influence. The Africans supplied the drum-heavy music of bomba y plena, while the Taíno contributed native elements to the most important part of the vejigante costume: the mask. As such, the Puerto Rico vejigante is a cultural expression singular to Puerto Rico.Similar to the masks of Puerto Rico, in Bahia, Brazil masked citizens dance through the streets.Also seen are large numbers of the Sons of Gandhi in Bahia.

The first Sons of Gandhi were dockworkers on strike in Salvador who were inspired by Mohandas Gandhi's philosophy of equality and nonviolent resistance to oppression. When they heard of his assassination, they decided to march at Carnival in his name.In Haiti, a controversy has erupted around censorship of Carnival songs.They needed costumes, of course, so the prostitutes from the docks gave them their sheets to use as robes, and towels to wrap around their heads. Dressed up to look vaguely Indian, the men marched through Brazil's first colonial capital.

The chants they still sing honor the Yoruba gods worshipped by many Afro-Brazilians. But 60 years ago, African religion was still systematically repressed by the dominant Catholic society. By garbing themselves in their namesake's philosophy of peaceful resistance, the Sons of Gandhi were able to bring their beliefs into the streets without provoking the police.

In a country where past carnival songs have predicted the fate of governments, lyrics are viewed as the social and political pulse of Haiti. Some bands behind controversial tunes say they were disinvited from this year's carnival. Now, as president of Haiti, some say Michel Martelly is banning other artists from taking part in this year's carnival celebration for doing the same thing he did as a singer: criticizing the government.In New Orleans, the black community is proud of its Mardi Gras Indians and second line, yet it is a tradition that is struggling to survive.Lead singers behind some of this season's most controversial carnival tunes - most of them critical of the Martelly government - say they were disinvited from being among the 15 bands to be featured on floats for this year's carnival.

"As young artists, we learned how to do this from him, watching him denounce government after government," said Don Kato of the group Brothers Posse, whose alleged ban has lit up social media and become a lead story for Haitian journalists. "It makes no sense that as an artist I can't sing about the environment I am living in, and you want to sanction me because I'm not singing in favor of you."

The documentary Flags, Feathers, and Lies, examines this tradition.

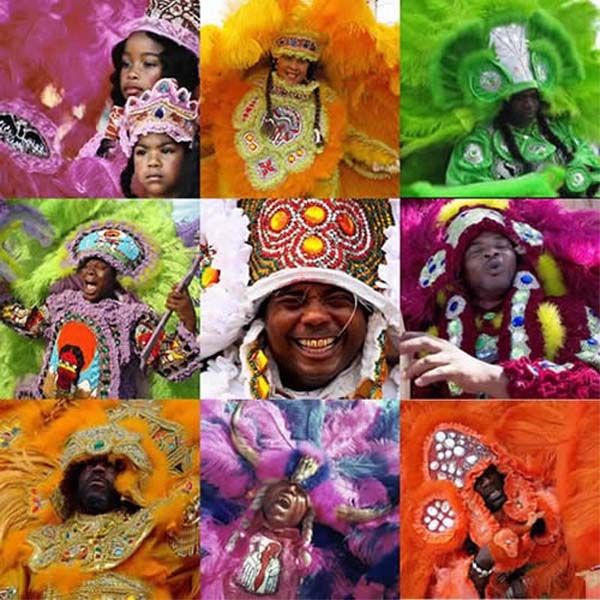

Behind the luxurious extravaganza of the famous Mardi Gras in New Orleans on the desolate back streets, devastated by Katrina, survives one of the most ancestral and hidden celebrations of the African-American population: “The Mardi Gras Indian”.Many of us are familiar with beat of Iko Iko, which references the flag boys of the Indians.The Mardi Gras Indians date back to the time of slavery as a tribute to the Native American tribes in Lousiana sho helped slaves runaway from the plantations seeking their freedom.

Dressed in splendorous costumes of bright feathers, the Indian Chiefs reenact with rituals and songs the roots and historical struggles of their community.These rituals and songs are one of the main sources of contemporary jazz music of New Orleans.

Nevertheless, this tradition, a cultural heritage of United States, is running the risk of disappearing due to racism and the displacement created by Hurricane Katrina.

Also part of black Mardi Gras tradition is the The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, known as the Zulu Crewe.

While the “Group” marched in Mardi Gras as early as 1901, their first appearance as Zulus came in 1909, with William Story as King.The group wore raggedy pants, and had a Jubilee-singing quartet in front of and behind King Story. His costume of “lard can” crown and “banana stalk” scepter has been well documented. The Kings following William Story, (William Crawford – 1910, Peter Williams – 1912, and Henry Harris – 1914), were similarly attired...

Zulus were not without their controversies, either. In the 1960’s during the height of Black awareness, it was unpopular to be a Zulu. Dressing in a grass skirt and donning a black face were seen as being demeaning. Large numbers of black organizations protested against the Zulu organization, and its membership dwindled to approximately 16 men. James Russell, a long-time member, served as president in this period, and is credited with holding the organization together and slowly bringing Zulu back to the forefront.So no matter where you are, come dance, sing, don your mask, parade and grab some beads.

Zulus were not without their controversies, either. In the 1960’s during the height of Black awareness, it was unpopular to be a Zulu. Dressing in a grass skirt and donning a black face were seen as being demeaning. Large numbers of black organizations protested against the Zulu organization, and its membership dwindled to approximately 16 men. James Russell, a long-time member, served as president in this period, and is credited with holding the organization together and slowly bringing Zulu back to the forefront.So no matter where you are, come dance, sing, don your mask, parade and grab some beads.In 1968, Zulu’s route took them on two major streets; namely, St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street, for the first time in the modern era. Heretofore, to see the Zulu parade, you had to travel the so-called “back streets” of the Black neighborhoods. The segregation laws of this period contributed to this, and Zulu tradition also played a part. In those days, neighborhood bars sponsored certain floats and, consequently, the floats were obligated to pass those bars. Passing meant stopping, as the bars advertised that the “Zulus will stop here!” Once stopped at a sponsoring bar, it was often difficult to get the riders out of the establishment, so the other floats took off in different directions to fulfill their obligations.

Carnival is a festival for us all today.

We can worry about tomorrow later.