Gauguin Exhibition

Strikes Controversy:

Should An Artist Be Docked

For Personal Indiscretions?

First Posted: 02/21/2012

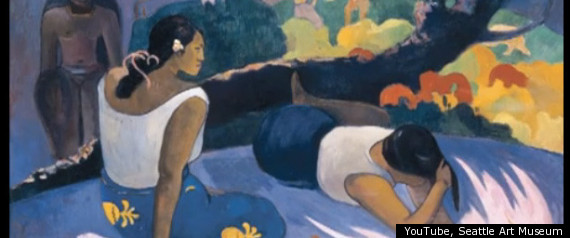

Almost as legendary as Paul Gauguin's colorful depictions of Tahitian utopia is the colorful story of how he got there and what he did once in the tropical locale -- the bourgeois stockbrocker picked up and left his wife and five children to embark on a hunt to discover the primitive. After testing out and abandoning lands not quite savage enough, Gauguin landed in Tahiti, where he indulged in the native lifestyle of taking adolescent girls as wives.

Decisions like impregnating a thirteen year old and giving her syphilis surely cast Gauguin in an unflattering light. And yet the artist's unethical and perhaps delusional escape to paradise led to one of the most revolutionary shifts in the visual vocabulary of all time. Gauguin's Primitivism used flat fields of acidic and unnatural color to convey stories that bridged history, myth, legend and dream. The utopias he painted expressed mystery, desire and the dark regions of psychology. This idea of making the invisible visible helped pave the way for contemporary abstraction. And no matter how you view it, the guy is an influential artist, even if he's someone you wouldn't want to take home to meet the folks.

What role, if any, should Gauguin's questionable ethics play in the reception of his art work? A recent review of Gauguin's exhibition at the Seattle Museum of Art by Jen Graves was hailed by some and reviled by others for enacting a personal critique of Gauguin as opposed to a purely aesthetic one.

Graves' article "You May Be Infected Already" on the exhibition "Gauguin & Polynesia" contains grating blows at Gauguin's persona, calling him, not-so discreetly, "vividly, eye-catchingly gross." Graves points out that Gauguin precipitated not only primitivism but also colonialism with a nice dash of misogyny. She applauded the SAM's exhibition for placing Gauguin's work in the context of Polynesian work in general, thus placing his delusions in close proximity with the islands' realities. Viewers get to see the European interpretation and the Tahitian interpretation, perhaps translatable to the orientalist interpretation and the native translation. Graves applauds the curators "who expose Gauguin's fantasies rather than indulge them." The exhibition does not simply worship Gauguin, it also unmasks him.

The comments section of the article exploded on both ends. While some backed Graves' morally inclusive reading, others declared her of being blinded to the art by the history of the artist. One comment by user Paddy Mac read:

"Huh. And what would you say about that sell-out Michelangelo? Or that violent drunk, Ernest Hemingway? You disqualify the art because of the misbehavior of the artist. Then how do you qualify it?"Once you start looking at artists who behaved badly and disqualifying them for it, it becomes clear how many brilliant minds turned out to be horrible people.

The question is a tricky one. Is an artwork made by a racist inherently racist? Or is mulling over the artist's personal beliefs overlooking the image in front of you? In cases like Gauguin's, indecent actions can get buried in the past and become almost amusing additions to an artist's portfolio. Current moral offenders seem to suffer more for their personal decisions, from Woody Allen to Roman Polanski to the latest controversy over Chris Brown.

What do you think? Does talent allow one to ignore the social code? Does historical ingenuity compensate for personal faults? Let us know your opinion in the comments section.

Below are materials from "Gauguin & Polynesia", now on view at the Seattle Museum of Art until April 29.

__________________________

YOU ARE IN PARADISE

by Zadie SmithJUNE 14, 2004

If you are brown and decide to date a British man, sooner or later he will present you with a Paul Gauguin. This may come in postcard form or as a valentine, as a framed print for your birthday or repeated many times across wrapping paper, but it will come, and it will always be a painting from Gauguin’s Tahitian period, 1891-1903. Chances are nudity will be involved, also some large spherical fruit. This has happened to me three times with three different men, but on only one occasion did the color of my skin appear to push us out into the South Seas themselves. I say my skin, but, as with any passion, this was a generalized one. M liked anything that lurked around the equator: Herman Melville, the early explorers, pirates, breadfruit (or the idea of breadfruit), and native girls of all varieties. We booked a holiday to Tonga. In normal circumstances, I would never be receptive to such an idea. I holiday in only one way: in my own house, on my balcony. (Or, at a stretch, in a hotel in Europe.) On this occasion, though, I was halfway through writing a novel. If a man with a canary had beckoned me to follow him down a mine, I would have gone. For the twenty-six hours of our flight, M sat next to me, very merry in his specially purchased straw hat, and I was merry, too, working away at the free wine, but I think that, while M knew all the time we were going to Tonga, I still somehow expected to land in lovely, temperate Antwerp. I remember stepping onto Nuku’alofa’s roiling tar runway in the face-melting heat and thinking, I have come to a country with no white tube-thingy, where you must walk along the roiling tar runway in the face-melting heat. How did this happen? Next thing I knew, we were on a boat so small that only the boatman, M and I, and one other couple could fit in it. It seemed appropriate to ask them if they came here often.

“Us? Often?” the man cried.

They were English, and a throbbing, comic-book red all over.

“Well, it’s paradise, isn’t it?” the woman said reverently, as we all looked out toward the island we were heading for in our small boat.

“It’s beyond your imagination,” the man said. “We never would have dreamt it. It’s the holiday of a lifetime. But we won the lottery, didn’t we?”

I thought he meant this figuratively, as in “life’s lottery,” as in “lucky us, going on our upscale holiday with similarly lucky people like you.” But no. They’d won the actual lottery.

“This is the first thing we bought!” the woman said. “But how can it get better than this?”

Much has been written about the horror of upscale holidays, of the strange metaphysical loneliness instilled by constantly being informed by fellow-tourists that you are in paradise, of how the pleasures offered to the tourist mix poisonously with said tourist’s personal guilt/shame regarding his or her relative wealth when compared with the indigenous people serving him or her tall cool glass after tall cool glass of Fuzzy Navel. Take all that as read. Also take as read the German-owned island, the existential misery of our Tongan waiters, the enforced “native entertainments” on a Sunday evening, and the Americans next door who had brought their own TV. What makes the whole thing stand out in my memory is my neurological reaction. I am an allergic person by nature: cats, dogs, horses, mosquitoes, and all facial products. But I have never before found myself allergic to a whole country. Allergic to its insects, its sand, its coral, its food, and—the clincher—its water. We had booked for two weeks, but five days into the holiday of a lifetime my windpipe began to close. I felt bad for M. He had his dream, and I was ruining it. He had his fale (traditional bungalow made of coconut fibre) and his hammock and his circle of beach. In the middle of this ring there was a brown girl, but Gauguin wouldn’t have painted her. Her right arm was twice its normal size, her left eye would not open, her legs were bleeding. And she wouldn’t stop whining. She refused to be excited by the fact that many Tongans can hold their breath underwater for an abnormally long time. That the men dress as women until they come of age. That the millennium would arrive here before it arrived anywhere else.

By the sixth day, M had given up on me. He made friends with a uniquely cheery Tongan waiter named Tony, who, interestingly, still wore women’s clothing. They would sit together on our deck looking out at the ocean, sometimes playing Scrabble, while I sat indoors wrapped in a cocoon fashioned from mosquito netting. If you squinted, eliding Tony’s fearsome biceps, you could imagine that M had met his Gauguin princess at last. ♦

>via: http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2004/06/14/040614fa_fact3

__________________________

Preview 2010 B3 FeatureLabs Project

"Gauguin's Lover"

Hmm... curious about this one.

A feature film currently seeking financing that was one of 7 projects that were accepted into the 2010 B3 FeatureLabs in the UK (similar to the IFP and Sundance Labs here in the USA) - a script development program that works with filmmakers to assist in seeing that they realize their full-length feature films for eventual commercial release. FeatureLabs is in partnership with Film4, and other collaborators.

Titled Gauguin's Lover (as in Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin, the French Post-Impressionist artist), the film is said to be inspired by Gauguin's 1892 oil painting Spirit of the Dead Watching, which depicts a nude Tahitian girl (Gauguin's 14-year old Tahitian wife Tehura) lying on her stomach, with an old woman seated behind her, and the little known fact that Gauguin gave his lover syphilis.

In anticipation of the question... my understanding is that Tahiti, the popular tourist destination I'm sure we've all heard of, is a French Polynesian island off the Pacific Ocean, with a population that comprises of indigenous Polynesians as well as people of African,European and Mesoamerican descent.

But I'm working to get more info from the filmmaker (Devika Ponnambalam) on her intent with the work here, and where the project currently stands...

In the meantime, watch the promo below: