Friday, July 6, 2012

The "negão" and

the fetishization of

interracial sex in Brazil

How do stereotypes, perceptions and expectations influence how men and women interact with each other when they are of different races or ethnic backgrounds? In the racialized world in which we live, if a white woman becomes intimate with a black man, are there certain expectations that she has of a black man that she wouldn’t have of a white man simply based on perceived notions, hearsay and stereotypes? Whether people tend to accept stereotypes as true or ignore the stereotypes and judge each person as an individual, there will be those who will use particular stereotypes to their advantage. As this is somewhat of a follow up to part one on the fetishization of the black Brazilian male body, let's consider the story of Cleyton, a 6'1", 27 year old man from Rio de Janeiro.Cleyton takes advantage of the image of the black male by renting out his sexual services to women through Rio's newspapers. After only 6 months in the game, Cleyton was already charging a pretty penny for his services. His clients are middle and upper class 30-ish women, the majority being married and "curiously, all white". Sometimes these women are actually accompanied by their husbands.

"I don't understand how the life of two apparently happy (people) need a third (person)", says Cleyton. What is it that these women are looking for in him? Do they ever say? "Yes. They believe that black men are more passionate, more active and mainly more hung." Cleyton suspects that his clients would not date black men even if they could. "I am a pure fetish, they don't openly accept crioulos (niggas)", he says with certainty and a touch a irony. Cleyton details one of his many trysts.

"One of the women that sought my services said that she has only been happy with black men, but because of family barriers, she couldn't marry him. From then and up to now, her extra-conjugal life limits itself to black men".

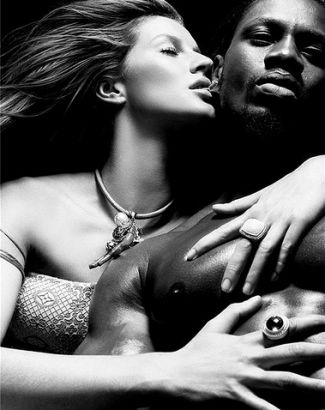

Model Gisele Bündchen

When asked what couples seek in his services, he says:"Generally, it is the husbands, always white men, that appear and request that I perform the role of the strong, virile, masculine man", a role that he never turns down. Lest we think that Cleyton's story is only one example and not enough from which to draw any conclusions, anthropologist Laura Moutinho interviewed many white Brazilian women for her book Razão, “cor” e desejo on interracial relationships and she reported that these women consistently told her that black men were "hotter", "more virile" and sexually superior to white men. This idea in regards to black men is by no means new or restricted to Brazil. Consider the 2007 story that revealed older white women traveling to Kenya for sexual tourism. Or the 2005 film Heading South (Vers le sud) based on white women traveling to Haiti for the same purposes. Haitian-Canadian Dany Laferrière certainly played on this image with his provocatively titled How To Make Love To A Negro Without Getting Tired (Comment faire l'amour avec un nègre sans se fatiguer), a 1985 novel which would be turned into a film. And if anyone is in doubt about the stereotype in the US, a quick visit to the DVD store, or better yet, a Google search of terms like "BBC" will show why interracial porn is such a niche market. Sure these stereotypes certainly help sell a lot DVDs by those who continue to fetishize interracial sex, but again, my question is, do these images somehow improve the global image of black men or do they contribute to their denigration?

Beyond all of the "is it true what they say" hype, how would a relationship play itself out if a man didn't quite live up to the image that the woman had of him if this image wasn't necessarily true? If a man who is racialized as the “other” doesn’t meet the established standard of what his race is imagined to be, is there a penalty for this “shortcoming”? In this given scenario, how should this interaction be dealt with?Gisele Bündchen

Beyond all of the "is it true what they say" hype, how would a relationship play itself out if a man didn't quite live up to the image that the woman had of him if this image wasn't necessarily true? If a man who is racialized as the “other” doesn’t meet the established standard of what his race is imagined to be, is there a penalty for this “shortcoming”? In this given scenario, how should this interaction be dealt with?Gisele Bündchen

Raquel Souza’s research provides an excellent example of the ways that images and stereotypes connected to ideas about race play out in matters of sexual relationships and expectations. Below, I cite liberally from the work of Souza on the topics of race, perceptions and meanings in the interactions between black men and white women in Brazil’s two largest cities, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Souza's research deals with perceptions of what it means to be a man. In terms of the connection between manhood and sexuality, here are the comments of two black men, ages 23 and 20, that Souza interviewed for the project.Marcos - "You have to be the man, you have to give pleasure to women. Previously, to prove that you were the man, you had the control, the issue was yours. If she didn’t feel pleasure, the problem was hers. No one even wanted to hear it. Only now you have that obligation to give pleasure to the woman. This is machismo, because you have to prove that you are good. In the past you didn’t have to do this."

Wagner – "In the past, the woman didn’t have access to information. Today, women have access to information and know how they want to have sex. She knows what she wants. If the guy is not good, she doesn’t stay with him. In the past it wasn’t like that."

With those comments in mind, read on as the following is an incident described by Rodrigues as told to her by Wagner, a single, 20-year black man from São Paulo:

It was in one of these strolls through Vila Madalena* that he met a middle class white girl, who told him about her preference for having relationships with black men, considering their physical specificities and skin color. The guy was surprised by the girl’s declaration as he didn’t fit this characterization because he was tall and thin and lacked a muscular physique. Despite the strangeness of that day, they exchanged affections, got together from time to time, and finally, making reference to the sexual act, they went to bed. Despite the girl's statement about her preference for black guys, Wagner found that during and after intercourse, the girl expressed fear that he would hurt her. She believed that black men had a different sexual potency and augmented genitalia. Wagner revealed that he was annoyed with her attitude:

"We had sex. Afterwards, she was like this (laughs)...We were having sex and she said: 'Be careful, look at your color and look at mine.' She said this! Oh, I said, 'Great!'. Then, after we had sex, she said that it had been different. But what's the difference? I had to talk to somebody about this, because I had never heard that in my life. I had heard this story that a negão (big, black man) has a different "pegada"**, which does damage, but for me, no one had ever said this. Who knows! I think I'm normal, I'm not that negão like that. (...) I’m very relaxed in relation to this [sex], like, I'm good, in my way. Up to the point that I had not had a relationship [losing his virginity], of course, you get nervous, you get very anxious, but then you discover how it is, then you relax. But you don’t expect certain comments. I think if I was on top of her only wanting to have sex, like, like the first time, wanting to knock it out and stuff, then you would expect a comment like that, but I didn’t do that. It was different because I’m calm, I expected her to say something different. Perhaps it could have even been unpleasant, like, 'Oh! You're so calm '. But, to say what she said didn’t hit me too good."

The implication of the girl clashed with Wagner’s self-image of a calm and quiet guy. He preferred that the girl would have perceived him as “normal.” The relationship did not continue and the experience was narrated by him as a new dilemma posed as a result of contact with new social groups, in which he had to negotiate ways of seeing himself and being seen. A perception about the singularity of black masculinity came across, with emphasis on sexual characters and body proportions - strength, height, violence, size. Now, it was no longer his (male) friend, who intentionally took care of his body, keeping it toned, and, therefore, having more prestige with the girls, but Wagner himself, by accident, was identified as a “typical” black man.

Wagner re-encountered in this experience different considerations and perceptions of white and black men, but now in his own experience, from an insinuation about his racial condition. As has been said, “aesthetic metaphors, virility, proportion, size and performance, are often invoked to differentiate the black man from the white man” (Moutinho 2004), evidenced in the sexual-erotic axis a sexual superiority of the former, a racial hierarchy that articulates moral and intellectual ability, beauty and eroticism. This difference, far from being grounded in empirical data, constructed on stereotypes about the black group, dating back to more atavistic ideas about these specificities and especially the type of relationship that is established when this man finds himself with a white woman.

Laura Moutinho (2004), analyzing the representation of interracial couples in Brazilian literature, notes that there is a taboo regarding the relationship between a black man and a white woman, whose destinies of couples like these are so constituted to invariably tragic outcomes, and commonly experienced episodes of sexual lust and rape. The embarrassment of Wagner at the situation seems to lie precisely in the girl's considerations about his sexual performance and a possible rape. Now, the fear of having seemed a little careful and therefore able to “knock it out” and cause “damage” seemed to bring to the fore his panic of possible insinuations about the advantages of his physical structure.

There are a few key points to analyze in Wagner's account of what went down between himself and a young white girl. First in the context of his comments and the comments of his friend Marcos, they both affirm that in order to be seen as a man and "the man", a male must be able to satisfy his partner sexually. While this wasn't true in the past, it is certainly true now and both men accepted this as a reality. Thus, going into his encounter with the young lady, Wagner brought with him a perception of manhood that he would have to live up to. But then when the sexual encounter took place with the young (white) woman, he was reminded of a second image that he needed to live up to: that of the virile, well-hung, dangerous, black man ("negão") whose rugged nature would dominate and cause "damage" to the unsuspecting white girl. But Wagner wasn't this type of black man and when he didn't live up to the image that she had of him, she laughed and said he was "different" from what she had expected of a black man. In his words, he was "normal" and "calm" when it seems that she expected "thug life."In Brazil, the image and stereotype of the black man is influenced by not only national images such as the capoeira*** master, the soccer player and national rappers, but the international image of the black American athlete, actor and gangster rapper also dominate the Brazilian media. In Wagner's view, he had been "othered" by a person of the opposite gender and race. He wanted to be seen as "normal" but part of the attraction that some women have for black men is associated with the "out of the ordinary", dangerous, aggressive, animalistic qualities that are the polar opposites of the image of society's standard bearer of masculinity, the white male. In essence, the black man, and black people in general, are victims of the double-edged sword: In the case of black men, although they wish to be accepted as normal, regular citizens

that are not constantly vilified in the minds of society, they also cherish certain qualities of being seen as the "other". In the scenario above, it is possible that Wagner would not have even been given the opportunity of experiencing intimacy with the young white girl if some or most of her perceptions of him weren't based on certain stereotypes of young, black males. On the other hand, had the myth of what black masculinity represented never been part of her imagination, maybe she wouldn't have judged him to be somehow "different" and thus possibly seen him as more of a complete person rather than some construction of society's imagination.Although Brazil is imagined to be a place where race doesn't matter and a place where the races mixes far more frequently than in Europe or the United States, racial differences, perceptions and stereotypes are just as frequent. There are an abundance of examples throughout this blog and this will become even more evident in future blog posts.

* - Vila Madalena is a upper middle class neighborhood of the Pinheiros district in the western part of the city of São Paulo** - One definition of "pegada" is footprint, but used in sexual terms, "pegada" means some exceptional quality that a man (or woman) has in terms of kissing, affection or having sex with someone. Researching the term online, various persons defined "pegada" in this way: the touch, when a person knows how bring out the desire of another person, to be good in bed, a certain style of affection.

*** - Capoeira is a Brazilian martial art that combines elements of dance, and music. It was created in Brazil mainly by descendants of African slaves with Brazilian native influences, probably beginning in the 16th century.

Sources: "Rapazes negros e socialização de gênero: sentidos e significados de "ser homem”" by Raquel Souza and "Homem fetiche" by Wedencley Alves from Black People, Issue 8, Year 2, Number 2.