A Christmas Killing:

Stagger Lee

“SHOT IN CURTIS'S PLACE

“SHOT IN CURTIS'S PLACE

“William Lyons, 25, coloured, a levee hand, living at 1410 Morgan Street, was shot in the abdomen yesterday evening at 10 o'clock in the saloon of Bill Curtis, at Eleventh and Morgan streets, by Lee Sheldon, also coloured.

“Both parties, it seems, had been drinking, and were feeling in exuberant spirits. Lyons and Sheldon were friends and were talking together. The discussion drifted to politics, and an argument was started, the conclusion of which was that Lyons snatched Sheldon's hat from his head.

“The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon drew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen [...] When his victim fell to the floor, Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away.”

- St Louis Globe-Democrat, December 26, 1895.

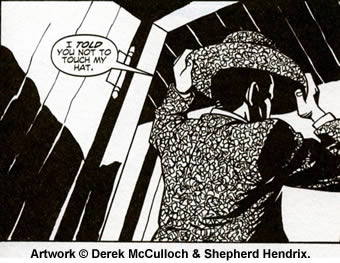

The new century's seen other media join in too. In 2006, Derek McCulloch and Shepherd Hendrix published a fat graphic novel telling Stagger Lee's story in careful detail. Movie versions have come from Samuel L Jackson, who gives a storming live rendition of the song in 2007's Black Snake Moan, and Eric Bibb, who uses it to comment on the action unfolding around his character in the following year'sHoneydripper.

All these versions tell the same core story, but no two of them seem able to agree on the details. A man named Stack Lee - or Stagger Lee, or Stack O'Lee - goes to a bar called The Bucket Of Blood - or sometimes The White Elephant - where he kills a man called Billy Lyons - or Billy Lion, or Billy DeLyon - for stealing - or winning - his Stetson hat. The story takes place in St Louis - or Memphis or New Orleans - in 1932, 1940 or 1952. Sometimes Stack kills the bartender first for disrespecting him and then moves on to Billy, who's done nothing to offend him at all. He's a sadistic killer in one version and a wronged innocent in the next. All these songs are about Lee Shelton - or “Sheldon” as the Globe-Democrat initially had it - but who was he?

To answer that question, let's start by looking at the city where he lived. St Louis had built its prosperity as a busy riverboat port, servicing the hundreds of steamers that sailed up and down the Mississippi between Minneapolis and New Orleans. This brought a constant traffic of gamblers, drifters and riverboat workers, all anxious to raise hell in St Louis for a day or two before continuing their journey. Itinerant railway workers joined the party in the 1850s, as St Louis became a key conduit point for pioneers heading west. The end of the Civil War in 1865 brought a huge increase in St Louis' black population, as former slaves flooded up from the South for the new factory jobs and the greater liberty which a Northern city promised to provide.

Wages for all these new workers were low, but still gave them more disposable income than they'd ever had before, and they all needed somewhere to burn up their paycheck on a Saturday night. In 1874, the Mississippi was bridged at St Louis for the first time, opening the city's riverfront vice districts to the even rougher residents of East St Louis, just across the river. St Louis' population increased seven-fold between 1850 and 1900, reaching 575,238 as the new century began(1).

As all these new developments tumbled forwards, law and order struggled to keep pace. The city's first police force was not established until 1861, and it's courthouse not completed till the following year. Thirty years later, the novelist Theodore Dreiser, then a young court reporter, found corruption was still rife at the notorious Four Courts in Chestnut Street.

“A more dismal atmosphere than that which prevailed in this building would be hard to find,” he wrote. “Harlots, criminals, murderers, buzzard lawyers, political judges, detectives, police agents and court officials generally - what a company! [...] The petty tyrannies that are practiced by underlings and minor officials! The 'grafting' of low, swinish brains! The tawdry pomp of ignorant officials! The cruelty and cunning of agents of justice! [...] To me, it was a horrible place, a pest-hole of suffering and error and trickery” (2).

The Four Courts governed Chestnut Valley, the city's busiest vice district, where black and white prostitutes alike worked around the clock. Even the humblest customers could find somewhere to get soused there, thanks to the many establishments selling “nickel shots” of rot-gut whiskey at just 5c a hit.

It was also an area where the normal segregation of the races was forgotten, allowing blacks and whites to intermingle and even have sex together. When business was slow in the valley's main streets, the girls would draw attention by knocking on the windows of each bar they passed. This habit was much resented by the other prostitutes working inside the bars, and would sometime spark an entertaining catfight in the gutter outside. What policing there was in Chestnut Valley was likely to be brutal, racist and crooked, as witness the case ofDuncan & Brady, the story of a murdered cop, which inspired its own St Louis ballad in the 1890s.

Small wonder, then, that the St Louis of 1895 ended up as a city of only 500,000 people - about the size of Leeds or Albuquerque today - where six murders could take place in a single night. Translate that rate to London's modern population of about 7.5 million, and you'd have 90 corpses littering the streets by dawn.

Small wonder, then, that the St Louis of 1895 ended up as a city of only 500,000 people - about the size of Leeds or Albuquerque today - where six murders could take place in a single night. Translate that rate to London's modern population of about 7.5 million, and you'd have 90 corpses littering the streets by dawn.

About ten blocks south of Chestnut Valley, St Louis had another red light district called Deep Morgan. The two main bars in this part of town were the Bridgewater Saloon on the corner of Eleventh Street and Lucas Avenue, and Curtis' Saloon on Thirteenth and Morgan. The two saloons were bitter rivals, and not only because they vied for the same business. Henry Bridgewater was a prominent black Republican, while Bill Curtis' saloon seems to have served as a meeting place for Democrat activists.

Curtis' joint had a particularly bad reputation. The St Louis Post-Dispatch counted it among the “worst dens in the city”, calling its clientele “the lower class of river men and other darkies of the same social status” (3). Lyons had good reason to think of this place as enemy territory. He was Bridgewater's brother-in-law, and had been attacked at Curtis' before.

Cecil Brown, author of 2003's Stagolee Shot Billy, has used the witness statements from Lyons' inquest to compile an account of the night's events. We know from these statements that Lyons left Bridgewater's Saloon with his friend Henry Crump, and that the two men walked the few blocks to Curtis' together. Lyons paused at the entrance to borrow a knife from Crump, and then they went in. He bought himself a drink at the bar, turned round, and saw Shelton walking in.

Shelton was a local carriage driver who sometimes moonlighted as a waiter at Curtis'. He was also one of the flamboyant St Louis pimps known as the “Macks” or “Macquerels”, using his two legitimate jobs to find potential clients for his stable of girls. He also ran his own Deep Morgan “lid club” called The Modern Horseshoe, which used an apparently legitimate bar out front to conceal illegal gambling and prostitution in its back rooms.

Shelton's prison records show he was 5' 7” tall with a crossed left eye and a light enough skin to suggest mixed parentage. He seems to have been dressed in full pimp regalia that night including - perhaps - the fashionable John B. Stetson hat which all the black dandies of Chestnut Valley considered essential wear.

Shelton joined Lyons at the bar and the two began drinking together in what onlookers thought was a friendly way. Everything was fine until, as the Globe-Democrat put it, “the discussion drifted to politics”. Here's how Brown reconstructs what happened next:

“Then Lyons grabbed Shelton's Stetson. When Shelton demanded it back, Lyons said no. Shelton said he would blow Lyons' brains out if he didn't return it. Next, Shelton pulled his .44 Smith & Wesson revolver and hit Lyons in the head with it. Still Lyons would not relinquish the hat. Shelton demanded the Stetson again, saying that if Lyons didn't give him his hat immediately, he was going to kill him.

“Then Lyons reached into his pocket for the knife his friend Crump had given him and approached Shelton saying 'You cock-eyed son of a bitch, I'm going to make you kill me'. Shelton backed off and took aim. The twenty-five people in the saloon flew for the door. [...] Both bartenders later testified to the coroner that they saw Lee Shelton shoot Billy Lyons” (4). Shelton calmly left the saloon, walked to a house he used on Sixth Street, left the gun with a woman there, and went to sleep upstairs. The police tracked him there and arrested him at about 3:00am on Boxing Day. Lyons was taken to the City Hospital where, after an operation to remove his lacerated left kidney, he died at about 4:00 o'clock the same morning. His death certificate shows he was 31 years old and unmarried.

Shelton may have taken his 'Stack Lee' nickname from a white man called Stacker Lee, whose father owned the famous Lee Steam Line of riverboats. Stacker Lee joined the Confederate army at the age of 16, became a cavalryman, and fought Yankees for the next two years. He was still only 18 when the war ended in 1865, and returned to civilian life determined to have some fun. When his father, James Lee, started the Lee Line a year later, he gave his son one of the boats to captain and Stacker set about making up for lost time. Travelling up and down the Mississippi between St Louis and New Orleans, he became well-known as a gambler, a hell-raiser and a ladies' man. He made a habit of fathering illegitimate children wherever his boat put in, often by black or mixed-race women. In his 1948 book Memphis Down in Dixie, Shields McIlwayne reports that Stacker's popularity meant there were “more coloured kids named Stack Lee than there were sinners in hell” (5).

It's very unlikely that Shelton was really Stacker Lee's son - the dates and locations are all wrong for that - but he may well have adopted his nickname to hint at that possibility. Shelton's light skin, described by Jefferson Penitentiary as a “mulatto complexion”, would have made it easy for people to believe he had a white father. Who could blame him for hinting that father was the glamorous son of a powerful, rich family?

The Lee Line also had a riverboat called the Stacker Lee, built in 1902 and named after the white cavalryman. It joined the fleet too late to influence Shelton's choice of nickname, but its regular trips between St Louis and Memphis may well have helped to spread his story's fame and spark new versions of the song. Other boats from the Lee Line inspired blues songs of their own, most notably Charley Patton's 1929 Jim Lee Blues, but only the Stacker Lee came with a ready-made legend attached.

The Lee Line also had a riverboat called the Stacker Lee, built in 1902 and named after the white cavalryman. It joined the fleet too late to influence Shelton's choice of nickname, but its regular trips between St Louis and Memphis may well have helped to spread his story's fame and spark new versions of the song. Other boats from the Lee Line inspired blues songs of their own, most notably Charley Patton's 1929 Jim Lee Blues, but only the Stacker Lee came with a ready-made legend attached.

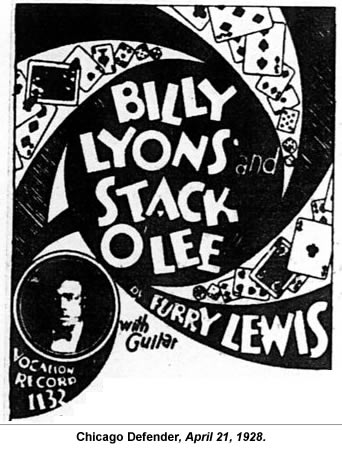

The first records to exploit that legend were instrumentals by white dance bands. Fred Waring's Pennsylvanians and Frank Westphal's Royal Novelty Orchestra released rival versions of a foxtrot called Stack O'Lee Blues in 1923, which sounds nothing like the tune we know today. Duke Ellington's Washingtonians added their own recording of this instrumental in 1927.

The first black version of the song committed to wax was Ford & Ford's Skeeg-a-Lee Blues, released by Paramount in 1924. Ma Rainey recorded a jazzy song called Stack O'Lee Blues two years later, but took the tune and some lyrics from Frankie & Albert, another St Louis murder ballad of about the same vintage. Rainey makes no attempt to tell the story of Billy Lyons' killing. Her Stack O'Lee is certainly a villain but his sin, like Albert's, is treating his woman badly. “He was my man,” Rainey groans. “But he done me wrong.”

The first records based on the real murder arrived in 1927. An early Mississippi bluesman called Little Harvey Hull and his trio The Down Home Boys put a subversive spin on the tale with their Original Stack O'Lee Blues. Accompanied by a slow-picked acoustic guitar, Hull sings:

'How can it be,

You arrest a man that's as bad as me,

But you won't arrest Stack O'Lee?'

And it's oh, Stack O' Lee!” [...] “Standing on the corner,

Well I didn't mean no harm,

Well that policeman caught me,

Well he grabbed me by my arm,

And it's oh, Stack O'Lee!” (6)

It's clear from these verses that Hull casts Billy as a policeman - presumably a white policeman - and one who tries to arrest Stack on a trumped-up charge. It's also clear that Billy is a little afraid of Stack, and that Stack is confident enough to taunt this white authority figure to his face. When the cowardly, unjust, copper forces Stack to kill him, it seems like an entirely excusable crime, and we join Hull in an indulgent chuckle when Stack returns to his old roguish ways in the song's final verse. This treatment of Billy may have been inspired by the fact that Lyons had once worked as a watchman - what we would call a security guard, and only one step removed from the police.

Like many early versions of the song, Hull's take was released on a “race” label, aimed at an exclusively black audience and offering them a cathartic tale of a strong black man overcoming bigoted white authority. Stag had long been an anti-hero in the work songs and folktales telling his story, and most of the records following Hull's would take that line too.

Most, but not quite all. Mississippi John Hurt's version of Hull's tune, released the following year, contrasted Hurt's wonderfully pretty guitar playing with a resolutely unromantic set of lyrics:

What you think of that?

Stack O'Lee killed Billy Lyons,

'Bout a $5 Stetson hat,

That bad man,

Oh cruel Stack O'Lee! “Standing on the gallows,

Head way up high,

At 12 o'clock they killed him,

They was all glad to see him die,

That bad man,

Oh cruel Stack O'Lee!” (7) Hurt's delivery suggests a bone-weary sadness at the constant violence poor black communities like St Louis' would have had to endure. He begins by berating the police for refusing to arrest Stack earlier and reminds us again and again just how cruel this bad man is. Stack may have felt Billy's theft of his Stetson obligated him to kill the man, but Hurt clearly thinks that's ridiculous.

Hurt allows Stack a moment of dignity on the gallows - “head way up high” - but gives no sign of regretting his demise. When Beck came to cover Hurt's version of Stack O'Lee for a 2001 tribute album, he drove this point home by changing “They was all glad to see him die” to “We were all glad to see him die”. On this reading, even the song's narrator is glad to see the back of him.

Some people argue that this we/they discrepancy should be seen as evidence of unconscious racism. Only the white singers, it's claimed, are prepared to join in the rejoicing at a black man's death. McCulloch and Hendrix raise this point in their graphic novel, only to dismiss it almost instantly (8). White singers, they argue, re-make Stack in their own image as the song proceeds, and if their Stack is a white man, then how can the “we” be racist?

My own view is that the choice of pronoun depends less on the singer's race than on where he's decided to place himself in the song. A performer who wants to cast himself as a participant in the story becomes part of the crowd watching Stack's execution, and so uses “we”. Someone preferring to remain a neutral narrator of the tale, watching it all from outside, would naturally opt for “they”.

It's also worth noting that the record of white singers' and black singers' pronoun use is far more jumbled than the racism theory suggests. Tennessee Ernie Ford, Pete Seegar and Ralph Stanley are all white, and yet all have recorded versions of the song saying “they killed him” and “they were glad to see him die”. Among black artists, both bluesman Sonny Terry and Dom Flemons of the Carolina Chocolate Drops have used “we” and even “I”. And what are we to make of versions like the Beck one mentioned above, which uses “they killed him” and “we were glad” in two consecutive lines?

Shelton's casual attitude after the murder - he walked a few blocks to a house everyone knew he used and went upstairs to get some sleep - suggests he wasn't too worried about police pursuit. He may have assumed, with some reason, that one black man killing another in that particular part of town would simply be ignored. If so, he reckoned without Henry Bridgewater.

Shelton's casual attitude after the murder - he walked a few blocks to a house everyone knew he used and went upstairs to get some sleep - suggests he wasn't too worried about police pursuit. He may have assumed, with some reason, that one black man killing another in that particular part of town would simply be ignored. If so, he reckoned without Henry Bridgewater.

Bridgewater was one of the richest black people in St Louis, owning not only Deep Morgan's Bridgewater Saloon, but also other property worth nearly $15,000 in 1895 money. He was also a prominent Republican at a time when black Americans' initial loyalty to that party was starting to drop away. The Civil War had brought an end to slavery in 1865, and this was achieved under the Republican President Abraham Lincoln. That was enough to ensure that most blacks voted Republican when first given the chance to do so in 1870.

But, by 1895, few of the Republicans' promises had materialised and disillusionment was setting in. Democrat activists began recruiting crucial black voters in St Louis by arranging what they called “400 clubs” in the local bars. One of these clubs, headed by Shelton, is said to have met at Curtis' Saloon. Just a few blocks up the street, Bridgewater was hosting Republican meetings at his own bar.

Bridgewater's Saloon was a much more upmarket affair than Curtis', often entertaining the black celebrities of the day, and able to attract a wealthier clientele. But it was also rough enough for the St Louis Globe-Democrat of September 12, 1902, to call it “a den of vice” when reporting a recent murder there(9).

The picture at Curtis' and Bridgewater's alike seems to be one of wild debauchery progressing on the ground floor while sober political meetings were conducted in an upstairs room. It's a difficult juxtaposition for us to understand. How did pimps and saloon keepers at the worst joints in town end up playing such a pivotal part n the political process?

The answer lies in the city's ward system, which relied on informal “mayors” in each neighbourhood to organise the local vote and see that it was cast the right way. Saloon keepers were ideally placed to fill this role because they provided accommodation for the itinerant workers passing through town. Even though these workers had no interest in St Louis politics, they were given a vote in city elections. The saloon keeper had only to offer them a few free drinks at the bar for those votes to be cast any way he liked.

Membership of the 400 clubs and the sporting clubs where Shelton pimped his girls often over-lapped, allowing him to extend his influence over both. We know he was politically active because, just after his arrest, the financial secretary of Shelton's own 400 club wrote a letter of support to the St Louis Star-Sayings, calling him “our captain [...] our unfortunate member and brother” (10). The St Louis Post Dispatch of March 17, 1911, writing while Shelton was in jail, said he was “formerly a Negro politician” (11).

Take all these facts together, and it starts to look like Bridgewater might have dispatched Lyons to Curtis' Saloon that night to broker some kind of deal between Deep Morgan's Republican and Democrat factions. That would explain why eyewitnesses thought Lyons and Shelton spoke in such a friendly way at first, and also why things turned ugly when they started discussing politics. Bridgewater was married to Eliza Lyons, Billy's sister, and may have decided that only a member of the family could be entrusted with such a delicate task. The police knew Lyons as a “rowdy bully” who had once threatened drinkers at Curtis' Saloon by waving a big knife around, so Bridgewater would have felt confident he could defend himself.

When the police arrested Shelton on Boxing Day they took him to Chestnut Street police station and held him there. Next day, he was taken to the coroner's office on Eleventh Street for Lyons' inquest. Waiting at the entrance was a crowd of about 300 blacks from what one paper called “the Henry Bridgewater faction”, who hissed and cursed at Shelton as he approached. Even when the police summoned reinforcements and drew their weapons, the crowd refused to disperse. “Throughout the entire hearing, a large crowd of negroes was in attendance,” reported next day's St Louis Globe-Democrat. “As many of them as could pushed their way into the Coroner's office, while the others crowded the hallway and congregated near the Eleventh street entrance” (12).

One un-named informant at the inquest told coroner WJ Wait that Lyons had been shot as part of a vendetta which began five years earlier. He pointed out that Lyons' step-brother, Charles Brown, had killed a man called Harry Wilson in Bridgewater's Saloon back in 1890, but never been convicted of the crime. Shelton, he claimed, had sworn to avenge Wilson's killing, and that was why he shot Lyons. There's no other evidence to support the revenge theory, however, and Wait refused to take it seriously.

Bridgewater's men remained in place when the inquest was over, agreeing to go home only after Wait had assured them Shelton would be held in custody pending charges of first-degree murder. He was taken first to a holding cell, and then to jail. Judge David Murphy signed a warrant for first-degree murder against him on January 3, 1896, and bound him over to await trial.

Bridgewater's role did not stop at dispatching his men to the coroner's office. John David, author of 1976's Tragedy in Ragtime, has uncovered a sheriff's letter to Judge James Withrow saying Bridgewater had pushed for Shelton to be prosecuted. He also hired Orrick Bishop, the city's formidable Assistant Circuit Attorney, to prosecute the case. Without Bridgewater's influence - and money - it's also unlikely doctors at the city hospital would have gone to so much trouble to try and save Lyons' life. When those efforts proved fruitless, he ensured Lyons was buried in the Bridgewater family plot.

But Lyons was not the only one with money and power behind him. Only a day after he was arrested, Shelton had already recruited a top-flight lawyer of his own. Nat Dryden was a brilliant Missouri lawyer, who had secured the state's first-ever conviction of a white man for killing a black man.

But Lyons was not the only one with money and power behind him. Only a day after he was arrested, Shelton had already recruited a top-flight lawyer of his own. Nat Dryden was a brilliant Missouri lawyer, who had secured the state's first-ever conviction of a white man for killing a black man.

He was also an alcoholic and an opium addict but these habits did nothing to inhibit his courtroom performance. Dryden was a fierce cross-examiner and a powerful orator. He'd proved himself capable of winning even the most unpromising murder cases, and he would not have come cheap.

Either Shelton was a wealthier man than his lifestyle suggests, or he had rich friends. On January 4, 1896, he paid $4,000 bail to get out of prison while he waited for his trial. He was jailed again later that year, on what seem to be unconnected charges, and freed again after someone called Morris Schmit provided another $3,000 in bail.

With Bishop in one corner and Dryden in the other, Shelton's trial was shaping up as a fascinating proxy fight between St Louis' leading politicians. The St Louis Globe-Democrat of July 14, 1896, could hardly contain its glee. “The trial promises to develop (into) a very pretty and interesting legal fight,” it drooled (13).

It's this same Globe-Democrat piece, incidentally, which seems to have introduced the idea that Shelton and Lyons were gambling with dice when the fight broke out. “The man who is now on trial for his life was shooting craps with William Lyons,” it claims. In fact, there's no mention of gambling in either the earlier newspaper reports or the inquest statements. Either the reporter responsible was genuinely confused, or he could not resist embellishing the story with one extra little colourful detail. Whatever its beginnings, the gambling is now an immovable part of the song. In many versions, it's Billy's alleged cheating at craps that prompts Stag to shoot him.

Shelton's trial began on July 15, 1896, and lasted just three days. Dryden accepted that his client had shot Lyons, but argued it was done in self-defence. On July 18, after 22 hours' deliberation, the jury returned with a split verdict. Seven of them voted for second-degree murder, two for manslaughter and three for acquittal. Judge Harvey dismissed them and ordered a retrial. Shelton returned to his old life.

Dryden died after a drinking spree on August 26, 1897, while Shelton was still waiting for a retrial. No records of the second trial survive. We know only that it must have come soon after Dryden's death and that it did not end well for Shelton. On October 7, 1897, he entered Missouri's Jefferson City Penitentiary to begin a 25-year sentence. Now he had a new alias to add to his list: Prisoner 579.

There was a steady flow of Stagger Lee covers in the 30 years following Mississippi John Hurt's recording, including versions by Woody Guthrie, Cab Calloway, Sidney Bechet, Memphis Slim, Fats Domino and Jerry Lee Lewis.

The British skiffle boom of the late 1950s brought a particularly strange take on the song from Chas McDevitt, who rewrote the story to have Stackolee steal the singer's Stetson hat and then flee. Forced to wear “a coon-skin cap instead”, McDevitt was now out for revenge. “I won't rest now until I shoot you dead,” he warned. “I'm looking for you bad man Stackolee.” Just in case that wasn't scary enough, he topped things off with a spot of the group's trademark whistling (14).

McDevitt failed to trouble the charts with that offering, but Stag's debut as a pop star was not far away. His big break came in 1959, when Lloyd Price made the song a number one hit in America and a number seven hit in the UK. Price, a black native of New Orleans, had a considerable musical pedigree. He'd written Lawdy Miss Cawdy in 1952 and scored his own number one R&B hit with the song long before Elvis Presley covered it.

Price racked up three more hits and then, in 1953, found himself drafted for the Korean War. He spent the next three years touring US bases in Korea and Japan entertaining the troops with his own army band. Looking for ideas to spice up the act, he remembered a 1950 version of Stack-A-Lee by a New Orleans singer called Archibald. “There were hundreds of lyrics for the old song but no story,” Price later explained. “I put together a little play based on it. I'd have soldiers acting out the story while I sang it.”

Price got out of the army in 1956 and resumed his recording career. He got back in the US pop charts almost immediately with 1957'sJust Because, and then unleashed his own raucous version of Stagger Lee on the world. It's a runaway train of a record, fuelled by blaring horns and the backing singers' constant roars of encouragement. Drums thump like pistons beneath Price's powerful vocals and the raspingly abrasive sax solos which break in every time he pauses for breath. “It was Stagger Lee and Billy,

Two men who gambled late,

Stagger Lee threw seven,

Billy swore that he threw eight, “Stagger Lee told Billy,

'I can't let you go with that,

You have won all of my money,

And my brand new Stetson hat', [...] “Stagger Lee shot Billy,

Oh he shot that poor boy so bad,

Till the bullet came through Billy,

And it broke the bar-tender's glass.” (15) Even without the backing vocals constant refrain - “GO STAGGER LEE! GO STAGGER LEE!” - it's pretty clear where this version's sympathies lie. All Hurt's doubts about the killer's code of honour have vanished. In Price's account, Billy refuses to acknowledge Stag's winning throw at dice, and that makes him fair game. There's a moment of token sympathy for Billy - “that poor boy” - but Price soon gets back to cheering Stag on. Go, Stagger Lee! Shoot him again!

Unlike Little Harvey Hull's 1927 treatment, Price's version invites white folks in to join the fun. They could relish the vicarious thrill of imagining themselves both freer and more frightening than they'd ever be in real life while still enjoying the comforts which their safe, middle-class life provided. A character like Stag can be very attractive to white suburban listeners, as the critic Bob Fiore pointed out when discussing gangsta rap in 2003. “He lives a life of adventure, wealth, violence and indulgence,” Fiore said. “He gets to murder people who annoy him, then obligingly reminds the audience of the relative security of their own existence through his nasty and early demise. [...] To an audience that perceives itself constrained by new rules of decorum, he represents a kind of alpha-dog masculinity they can only dream of” (16).

Unlike Little Harvey Hull's 1927 treatment, Price's version invites white folks in to join the fun. They could relish the vicarious thrill of imagining themselves both freer and more frightening than they'd ever be in real life while still enjoying the comforts which their safe, middle-class life provided. A character like Stag can be very attractive to white suburban listeners, as the critic Bob Fiore pointed out when discussing gangsta rap in 2003. “He lives a life of adventure, wealth, violence and indulgence,” Fiore said. “He gets to murder people who annoy him, then obligingly reminds the audience of the relative security of their own existence through his nasty and early demise. [...] To an audience that perceives itself constrained by new rules of decorum, he represents a kind of alpha-dog masculinity they can only dream of” (16).

Even the dream was thought too dangerous for American TV viewers in the late 1950s, leading the presenter Dick Clark to insist Price cut a sanitised version of the song before he could appear on American Bandstand. In the bowdlerised lyrics, Stag and Billy argue rather than gamble, regret the harsh things they've said, and then part the best of friends.

Price's chart success with Stagger Lee made his version of events the template for many of the tellings that followed. It also made the song popular enough for artists in a couple of new genres to adopt it. Until 1959, Stagger Lee had mostly belonged to folk and blues musicians, with just the occasional jazz or country outing thrown in. Price's hit prompted soul and reggae performers to join in too.

Ike & Tina Turner opened soul music's bidding in 1965 by placing Tina in a dance club where she watched Billy beating Stag to a pulp for kissing his (Billy's) wife. The song fades out before Stag has any opportunity to take revenge. James Brown funked things up with The Fabulous Flames' staccato horns in 1967, the same year Wilson Pickett galloped through his own version. Both Brown and Pickett stick closely to Price's plot.

Meanwhile, Jamaicans were listening to US R&B on the radio, adapting its storylines and rhythms for their own use. Prince Buster liked Price's tune enough to create a rude boy called Stack O'Lee with his 1966 reggae version, prompting what was effectively an answer record the following year. The Rulers, an island rocksteady outfit, had already made a couple of records warning against the consequences of rude boys' delinquency, and saw Prince Buster's hit as an opportunity to drive this point home again. They openWrong 'Em Boyo with a couple of lines from Price's song to establish Billy's cheating ways, and then spend the rest of the song pointing out that this is really no way to behave.

When The Clash came to record their 1979 album London Calling, it was only natural that Wrong 'Em Boyo should come up as a candidate for one of their covers. Paul Simonon, The band's resident reggae expert, had ensured a copy of The Rulers' single found its way on to the jukebox at The Clash's Camden Town rehearsal rooms. Joe Strummer knew Price's version of Stagger Lee very well from his days performing it with his old pub rock band The 101ers.

The Clash sketch out a brief scene from Stag and Billy's fight with some lyrics of their own and then turbo-charge The Rulers' hit into a piece of what Charles Shaar Murray of the rock weekly NME called “tense, jumping ska” (17). Here's the key verses:

And they got down to gambling,

Stagger Lee throwed seven,

Billy said that he throwed eight, “Billy said 'Hey Stagger,

I'm gonna make my big attack,

I'm gonna have to leave my knife,

In your back'.” [...] “So Billy Boy has been shot,

And Stagger Lee's come out on top,

Don't you know it is wrong,

To cheat the trying man?

Don't you know it is wrong,

To cheat the Stagger man?

You better stop,

It is the wrong 'em boyo!” (18) The lines about Billy's knife, the reference to his shooting and the specific identification of Stag as the wronged party are all Clash additions to this composite song. The end result is to remove any possible ambiguity from The Rulers' version and make it clear that the scolding is directed at Billy alone. Never slow to glamorise an outlaw, The Clash use this cracking version of The Rulers' hit to give Stag his biggest vote of confidence yet.

Shelton had an eventful career in prison. He was less than 18 months into his sentence when, in March 1899, he was given five lashes for “loafing” in the exercise yard. Three months later, he was reprimanded for shooting craps. His Democrat friends outside the prison had not forgotten him, however, and continued to petition for his parole. Shelton helped things along by giving Jefferson City guards the information they needed to detect a “systematic theft” in the prison.

By 1909, the Bridgewater family were taking Shelton's chances of parole seriously enough to fight back. Eliza Bridgewater, Billy's sister, wrote to the parole board urging them to make Shelton serve his full sentence. “I hope and pray that you will never agree to let a man who never worked a day or earned an honest dollar be turned out to meet us face to face,” she wrote. “As a sister, I beg you not to turn a man like him on the community at large. If justice had been done, he would have hung. Just think, he has not served half his term” (19).

Despite Eliza's protests, Shelton got his parole and walked out of the prison at the end of November 1909. But he didn't stay out for long. In January 1911, he robbed a black man called William Atkins, breaking his skull with a revolver before stealing $60 from the house. He was caught, sentenced to five years, and returned to prison on May 7 the same year.

By then, Shelton was 46 years old and suffering from tuberculosis. Missouri's Democrat governor Herbert Hadley, pressured by others in his party, made one final bid to get him another parole, but this was blocked by the state's Attorney General. Shelton died in Jefferson City prison hospital on March 11, 1912. How many times had he heard his own story sung back at him by then?

By then, Shelton was 46 years old and suffering from tuberculosis. Missouri's Democrat governor Herbert Hadley, pressured by others in his party, made one final bid to get him another parole, but this was blocked by the state's Attorney General. Shelton died in Jefferson City prison hospital on March 11, 1912. How many times had he heard his own story sung back at him by then?

Of course, if the songs and folktales are to be believed, matters didn't end with Shelton's death. There's a strong tradition among New Orleans performers, perhaps stemming from Archibald's 1950 recording, which continues the story as Stag descends into hell, terrifies the devil and takes over his throne. This aspect of the story appears in the most unlikely places. Even the innocuous country crooner Tennessee Ernie Ford got in on the act with his 1950 Stack-O-Lee:

He holler 'Now listen to me,

Hide the children and the money,

'Cause Stack-O-Lee is worse than me'“Stack-O-Lee grabbed hold of the devil,

And threw him up on the shelf,

Said 'Your workin' days are over,

I'm a-gonna run the place myself'.” (20) Sometimes Billy ends up in hell too, allowing Stack to inflict still more punishment on him in the afterlife. Here's a verse from Dr John's 1972 version, Stack-A-Lee: “Now the devil,

Heard a rumbling,

A mighty rumbling under the ground,

He said 'That must be Mr Stack,

Turning Billy upside-down'.” (21) Folktales about Stack often link him to the devil too. Some claim he was born double-jointed or with a birth caul covering his face, both taken as signs of a demon child. Others have him do a Robert Johnson style deal with Satan, selling his soul at the crossroads to gain supernatural powers. One tale, collected by BA Botkin in his Treasury of American Folklore, even explains why Stack loved his Stetson hat so much:

“Stack was crazy about Stetson hats. [...] But his favourite was an oxblood magic hat that folks claim he made from the raw hide of a man-eatin' panther the devil had skinned alive. [...] You see, Satan heard about Stack's weakness, so he met him that dark night and took him into the grave yahd where he coaxed him into tradin' his soul, promisin' he could do all kinds of magic and devilish things long as he wore that oxblood Stetson and didn't let it get away from him. And that's the way the devil fixed it so when Stack did lose it he would lose his head, and kill a good citizen and run right smack into his doom” (22)

As Stagger Lee moved from one genre of recorded music to another, shifting persona as he went, there was one strand of his tale which remained firmly underground. No version of Stag's story sanctioned by the professional recording industry was ever going to be intense enough for real ghetto thugs to accept, so they produced their own “toasts” instead.

These were unaccompanied spoken-word accounts of Stag's life, chanted at the listener with percussive force and driving their points home through regular rhyming couplets. They were sexually explicit, usually told in the first person, and full of inventive swearing. Like the rappers who followed them, toasters could use these tales to portray themselves as charismatic, powerful gangsters who the white police held in awe.

The first Stagger Lee toast was collected in 1911. For the next 50 years, it was taken for granted that the toasts were far too foul-mouthed ever to make a commercial recording. Isolated from every respectable genre of music, they retained their own unique take on Stag's story. The Stetson hat is mentioned only in passing and Billy slips into the background. Instead, Stag's primary victim is the barman at a place called The Bucket of Blood. Sometimes the barman deliberately serves Stag with inedible food. In other versions, he first refuses to recognise him, and then treats him with utter contempt. Then Stag shoots him.

The barman's name is never given, but it's pretty clear that he represents Henry Bridgewater, the man most responsible for getting Shelton arrested and jailed after the real murder. He is Lex Luthor to Stag's Superman, and that's the aspect of the story which the toasts set out to commemorate. The Bucket of Blood, incidentally, was a real saloon/whorehouse in St Louis. Whether it had any connection with Bridgewater, I don't know, but someone obviously thought the name was too good to waste.

The first commercial recording of Stag's toast in anything like its uncut form appears on Snatch & The Poontang's 1969 album For Adults Only. The Poontangs - an alias for R&B veteran Johnny Otis and his band - provide a whole album of uncensored street toasts, delivered with all the panache you'd expect from such road-hardened performers. There's a great deal of swearing, springing mostly from the fact that everyone in the song seems to be a motherfucker.

Like most toasts of the song, The Poontangs' version can be traced back to one which appears in Dennis Wepman's 1986 book The Life: The Lore and Folk Poetry of the Black Hustler. Wepman includes a Stagger Lee toast performed by a black inmate called Big Stick at New York State's Auburn Prison in 1967. The words themselves are a great deal older than that:

Till he came to a place called the Bucket of Blood,

He said 'Mr Motherfucker you must know who I am',

Barkeep said 'No and I don't give a good goddamn',” “He said 'Well bartender it's plain to see,

I'm that bad motherfucker named Stagger Lee',

Barkeep said 'Yeah I heard your name down the way,

But I kick motherfucking asses like you every day', “Well those were the last words that the barkeep said,

'Cause Stag put four holes in his motherfucking head.” (23)

Nick Cave fans will find this extract from Big Stick's story very familiar. When Cave and his band, The Bad Seeds, were recording their 1996Murder Ballads album, Bad Seeds percussionist Jim Sclavunos brought a copy of Wepman's book into the studio. Cave discovered Big Stick's toast there, and had the band improvise a backing on the spot. Their brooding bassline, scratchy guitar and sudden, stabbling piano chords provide a perfect backdrop for Cave's supremely menacing vocals. He relishes every drop of cruelty the song provides, growling Big Stick's brutal words almost verbatim and drawing every ounce of value from their rhythmic punch. For the 5 mins 15 secs the song lasts, Cave seems both omnipotent and possessed. “I'M Stagger Lee!” he roars at one point. Who could doubt it?

Nick Cave fans will find this extract from Big Stick's story very familiar. When Cave and his band, The Bad Seeds, were recording their 1996Murder Ballads album, Bad Seeds percussionist Jim Sclavunos brought a copy of Wepman's book into the studio. Cave discovered Big Stick's toast there, and had the band improvise a backing on the spot. Their brooding bassline, scratchy guitar and sudden, stabbling piano chords provide a perfect backdrop for Cave's supremely menacing vocals. He relishes every drop of cruelty the song provides, growling Big Stick's brutal words almost verbatim and drawing every ounce of value from their rhythmic punch. For the 5 mins 15 secs the song lasts, Cave seems both omnipotent and possessed. “I'M Stagger Lee!” he roars at one point. Who could doubt it?

“Stagger Lee appeals to me simply because so many people have recorded it,” Cave told Mojo magazine in 1996. “The reason we did it, apart from finding a pretty good version in this book, was that there is already a tradition. We're kind of adding to that” (24).

The song's since become a highlight of the Bad Seeds' live set. Often, it's used to close the show, as seen in the DVD of the band's November 11, 2004, gig at London's Brixton Academy. As the song begins, violinist Warren Ellis is crouched at the back of the stage, facing away from the audience, his head bowed and his hands clasped round the instrument's neck. The music begins to build, and Ellis starts rocking back and forth in time with its slow burn. Head bowed, fists clenched, eyes tightly shut, he looks like a man praying to appease a dark and angry god - praying, perhaps, to Stagger Lee himself to forgive the band's temerity in daring to invoke his name.

From Little Harvey Hull through Lloyd Price to The Clash and Nick Cave, every serious incarnation of Stagger Lee can be seen as a strong black man doing whatever it takes to make his way in an unjust white man's world. Rich or poor, aggressor or otherwise, he's always Fiore's “alpha dog” and always ready to extract a terrible revenge on anyone who fails to treat him that way. It's no coincidence that James Brown recorded his own version of Stagger Lee in the same year he recorded his anthemic Say It Loud I'm Black And I'm Proud. Stag may not be the healthiest of role models, but he's always been a potent symbol of black pride.

He's also the grandfather of every drug dealer and pimp populating today's gangsta rap tunes. Eithne Quinn makes this point in her 2004 book Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang, where she calls Stag “(one of) the most influential badman forebears of gangsta rap”. She goes on to draw a direct comparison between his ballad's story and NWA's notorious 1988 track Fuck tha Police, which closes with a scene putting the white police themselves on trial for brutality. “The rebellious intent - pushing at the boundaries of what was permissable in its historical moment - matches that of 'Stackolee',” Quinn says. “Considerable pleasures were afforded by this Day-Glo repetition of the traditional tale: Stackolee meets the LAPD, as it were” (25).

Thousands of young people in poor black neighbourhoods all over America are still trapped in Stagger Lee's violent world. Maybe that's why Bobby Seale, the Black Panther leader, decided to name his son after Stag.

Speaking in a 1970 jailhouse interview, Seale said: “I named my son Malik Nkrumah Staggerlee Seale. Beautiful name, right? He's named after his brother on the block, like all his brothers and sisters off the block: Staggerlee. Staggerlee is Malcolm X before he became politically conscious. Livin' in the hoodlum world. You'll find out. Huey (Newton) had a lot of Staggerlee qualities. I guess I lived a little bit of Staggerlee's life too, here and there. [...] And at one time, brother Eldridge (Cleaver) was on the block. He was Staggerlee. And so I named that brother, my little boy, Staggerlee, because - that's what his name is” (26).

Draw a line from Stagger Lee through Seale's Panther buddies, and you come to gangsta rapper Tupac Shakur. The NME made this connection explicit when it reported on Shakur's latest problems in December 1994. In October 1993, Shakur had come across two off-duty Georgia cops who he believed were harassing a black man by the side of the road. He got into a fight with them and ended up shooting them both, one in the leg, the other in the buttocks. Charges against him were dropped when it emerged that the cops had been drunk at the time, and using weapons stolen from an evidence locker.

Two months later, Shakur was charged with sexually assaulting a woman in his hotel room and put on trial. In November the following year, while he was still waiting for a verdict, someone shot him five times outside a New York recording studio and stole the $40,000 worth of jewellery he was wearing.

That's where the NME picked up the story. “Why should Shakur sabotage his lucrative career for, as he calls it, a thug life?” the paper asked. “Fans of Tupac accuse the white community of missing the point. They say Shakur is a black hero in the tradition of blues archetype Stagger Lee, who created a system for himself based on his own perceptions. Writer Dream Hampton described Tupac's shooting of the two policemen as having 'mythic potential [...] black knight slays cracker dragons who emerge in the night, fangs bared. [...] It's the kind of community work we all dream of doing'.” (27)

Less than two years after that story appeared, Shakur was shot dead. He was leaving September 1996's Mike Tyson/Bruce Seldon fight in Las Vegas when a car pulled up next to his on the street and pumped 13 rounds inside. No-one's ever been caught for the crime, but police believe members of Los Angeles' Southside Crips were responsible. Biggie Smalls, the LA rapper who Shakur had always believed was behind the New York shooting, was killed in a drive-by six months later.

Less than two years after that story appeared, Shakur was shot dead. He was leaving September 1996's Mike Tyson/Bruce Seldon fight in Las Vegas when a car pulled up next to his on the street and pumped 13 rounds inside. No-one's ever been caught for the crime, but police believe members of Los Angeles' Southside Crips were responsible. Biggie Smalls, the LA rapper who Shakur had always believed was behind the New York shooting, was killed in a drive-by six months later.

We're still waiting for the definitive gangsta rap take on Stag's own story, but that's not to say that rap has ignored him altogether. A St Petersburg rock combo called Billy's Band recently produced a rap of Nick Cave's Stagger Lee. It's full of thunderous drums and rapped with a strong Russian accent. “This is the way things are going in the 'hood,” singer Billy Novik warns us. “It's just no damn good, hanging out in the 'hood”. No doubt today's gangster-ridden Russia can match anything thrown up by St Louis in 1895, so perhaps this version is less of a cultural oddity than it seems.

We've come a long way from Mississippi John Hurt's sober and saddened account of the damage Stagger Lee does to those around him. Each successive generation that takes on the song has darkened it, stepped a little more keenly into the killer's shoes and cast aside aside another scrap of whatever pity remains for Billy.

But, for Cave, it's the sheer sadism of versions like his that makes them so exhilarating. “What I like about it is that Stagger Lee's atrocious behaviour has nothing to do with anything but flat-out meanness,” he told Mojo. “I like the way the simple, almost naïve, traditional murder ballad has gradually become a vehicle that can happily accommodate the most twisted acts of deranged machismo. Just like Stagger Lee himself, there seems to be no limits to how evil this song can become.”

Appendix I: Ten versions you must hear

The Trial of Stagger Lee, by Stella Johnson (1961). This chug-along sixties soul version is set in a courtroom packed with women. They're all anxious to believe Stag's claim that he didn't know the gun was loaded, chanting “Not Guilty” at the far more sceptical judge. Stagger Lee, we conclude, is just too much man for any woman to want to see him jailed. Available on: An Introduction to Night Train New Orleans (Night Train, 2001).

Stagger Lee, by The Ventures (1963). The world's finest surf guitar act twang up Lloyd Price's tune to admirable effect on this long-neglected instrumental. Well worth the 36-year wait for Ace to exhume it. Available on: In The Vaults Volume 2 (Ace, 1999).

Stagger Lee, by Moustique (1963). There's a Dutch language Stackalee too - recorded by Meindert Talma in 2006 - but I prefer the French. Using Price's tune as their template, Moustique take full advantage of the “Stagger Lee: Mon Ami” rhyme which only their native tongue can offer. Available on: Twistin' the Rock (Universal, 1963).

Stagger Lee, by Dave “Baby” Cortez (1965). Cortez scored a couple of US chart hits with his R&B organ instrumentals in the late 1950s and early 60s. Here it sounds like he's playing an old cinema organ, with quick, shrill solos and a driving soul band beneath. Available on: Dave “Baby” Cortez (Sequel, 1995).

Stagger Lee, by Elvis Presley (1970). Presley was rehearsing for a show in Culver City, California, when this fragment of the song was recorded. The sound quality's not great, but you can hear he's enjoying himself. “I got 300 little kids,” he howls as the band loosens up behind him. “And a very horny wife.” Available on: Get Down & Get With It (Bootleg).

Stagolee's Victory, by The Savage Rose (1972). This Danish cult band pulls out all the stops for a full-on gospel treatment which makes Stag a metaphor for every oppressed black man in America. There's the hint of a New Orleans funeral march in there, some splendidly macabre lyrics (“Stagolee ain't got no eyes”) and a promise at the end that vengeance is coming. No wonder Bobby Seale's Black Panthers loved this band. Available on: Babylon (Universal, 1972).

Stagolee, by Dr Hook (1978). A disco-country take on the song by an international chart act sounds unlikely enough on its own, but the men behind Sylvia's Mother go a step further. This is one of the very few versions to foreground Stag's magic hat, explaining how the devil gave it to him and the powers of immortality it conveys. Available on: Vintage Years (EMI, 2003).

Stack O Lee Aloha, by Bob Brozman (1992). Brozman's isn't the first version to use the Hawaiian slack-string guitar style - that honour went to Sol Hoopi in 1928 - but it is the best. Based on an old Ray Lopez jazz tune, this jaunty instrumental conjures images of Stag with a .44 in one hand and a mai tai in the other. Irresistible. Available on: Truckload of Blues (Rounder, 1992).

Stack-O-Lee, by Tom Morrell & the Time Warp Tophands (1994). Morrell and his western swing pals canter through Billy's slaughter, Stag's hanging and his take-over of hell with the aid of a saloon piano and a perky pedal steel guitar. Murder, execution, damnation and revolt have never sounded so jolly. Available on: How The West Was Swung Volume 5 (WR Records, 1994).

Poor Man's Stagger Lee, by Stagger Lee (2007). The eponymous singer warns a woman that the no-good waster she's with is nothing but “a poor man's Stagger Lee”. Why can't she choose a hard-working good ol' boy like himself instead? A barbed-wire banjo accompaniment underscores his point, but we all know she isn't going to listen. Available on: Nashville Starfucker (NNMaddox, 2007).

Appendix II: Of women dressed in red & why the bulldog barks

Many versions of Stagger Lee throw up intriguing little puzzles which we can't hope to definitively solve today. The New Orleans strand, for example, often adds the detail that the women mourning Stag's death come “dressed in red”. Both Archibald and Dr John use this line in their versions.

One theory insists that this reflects an old African funeral custom, which dictated that mourning clothes should be the colour of blood. Another maintains that the line is imported from another St Louis murder ballad called Duncan & Brady, which relates the shooting of a famously strict lawman in the town.

Brady, the lawman in question, supposedly cracked down on St Louis' prostitutes, banning them from wearing the red dresses that advertised their trade. In the song, he's shot dead by a black store-owner he's been harassing. When the girls hear this news, they celebrate by digging out their red dresses again and strutting round town in them to celebrate.

When transferred to Stagger Lee, the line's context suggests they've dressed this way as an act of solidarity with their favourite dead pimp. Frankie & Johnny's Frankie Baker wears red in her ballad too, which early listeners may have recognised as signifying that she was also a prostitute.

The barking bulldog which shows up in Lloyd Price's version has sparked rival theories too. Some believe the bulldog represents Billy's soul as it's torn from his body in a violent death. Others point out that a popular revolver in the 1890s was nick-named “the bulldog” and claim it's therefore a handgun we hear barking in the song.

The British Bulldog - actually a Webley - was originally made for the British army in 1878, but was quickly copied by gun-makers all over Europe and the US. Its two-and-a-half-inch barrel was short enough for the gun to be slipped in a coat pocket and carried around in secret (28). Charles Guiteau took advantage of this fact in 1881, when he used his own Bulldog to assassinate US President James Garfield.

The British army contract ensured these guns were distributed all over the world, so they would have reached St Louis in plenty of time for Shelton to use one in 1895. The American copies, made by Forehand & Wadsworth, sold for as little as $5. It's a pleasing co-incidence that the guns used the same .44 or .45 calibre ammunition which Stag is often said to prefer.

Sources

1: Physical Growth of the City of St Louis, stlouis.missouiri.org/heritage/History69

2: A Book About Myself, by Theodore Dreiser (Constable, 1929).

3: St Louis Post-Dispatch, 21/2/1891.

4: Stagolee Shot Billy, by Cecil Brown (Harvard University Press, 2003). Brown's book remains the definitive history of Stagger Lee, and is highly recommended to anyone with an interest in the song.

5: Memphis Down in Dixie, by Shields McIlwaine (EP Dutton, 1948).

6: Original Stack O'Lee Blues, by Long Cleve Reed & Little Harvey Hull - The Down Home Boys. (Black Patti, 1927).

7: Stack O'Lee, by Mississippi John Hurt (Okeh, 1928).

8. Stagger Lee, by Derek McCulloch & Shepherd Hendrix (Image Comics 1996).

9: St Louis Globe-Democrat, 12/9/1902.

10: St Louis Star-Sayings, 29/12/1895.

11: St Louis Post Dispatch, 17/3/1911.

12: St Louis Globe-Democrat, 28/12/1895.

13: St Louis Globe-Democrat, 14/7/1896.

14: Badman Stackolee, by The Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group [Trad. Arr: McDevitt] (Oriole, 1957).

15: Stagger Lee, by Lloyd Price [Lloyd Price & Harold Logan] (HMV, 1959).

16: The Comics Journal, February 2003.

17: NME, 15/12/1979.

18: Wrong 'Em Boyo, by The Clash [Clive Alphanso, MCPS] (CBS, 1979).

19: Tragedy in Ragtime: Black Folktales From St Louis, by John R. David. (St Louis University, 1976).

20: Stack-O-Lee, by Tennessee Ernie Ford [Trad. Arr: Joe “Fingers” Carr] (Capitol, 1950).

21: Stack-A-Lee, by Dr John [Trad. Arr: Archibald] (Atlantic, 1972).

22: “A Treasury of American Folklore: Stories, Ballads and Traditions of the People”, by BA Botkin (New York, 1945).

23: Life: The Lore and Folk Poetry of the Black Hustler, by Dennis Wepman (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1976).

24: Mojo, January 1996.

25: Nuthin' But A “G” Thang, by Eithne Quinn (Columbia University Press, 2004).

26: Mystery Train, by Greil Marcus (Faber & Faber, 1975).

27: NME, 17/12/1994.

28: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Bulldog_revolver