Part 1:

The largest slave rebellion

in U.S. history

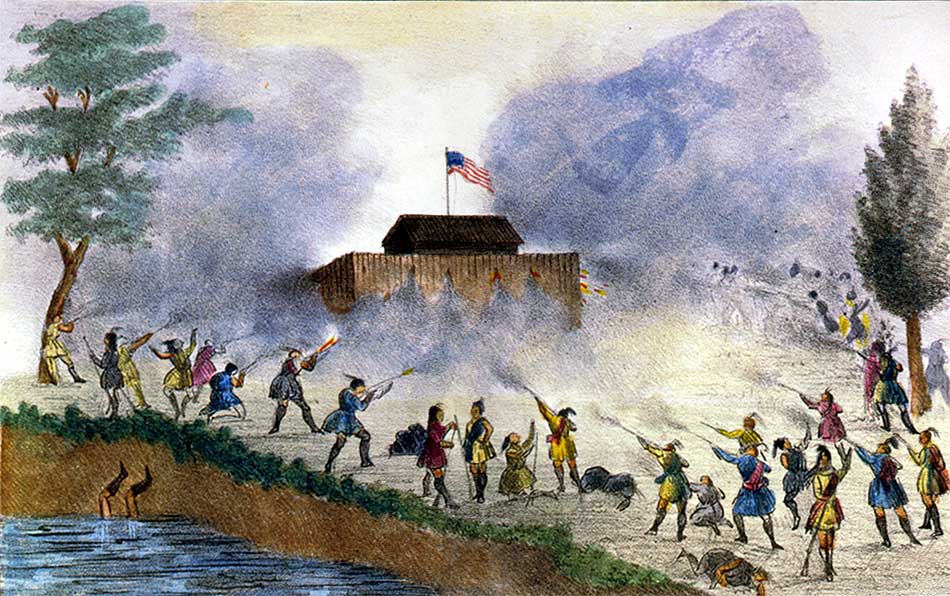

1836 wood engraving printed for Blanchard's narrative of the war. Caption reads: "The above is intended to represent the horrid Massacre of the Whites in Florida, in December 1835, and January, February, March and April 1836, when near Four Hundred (including women and children) fell victim to the barbarity of the Negroes and Indians." See key images for more detailed commentary. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, LC-USZ62-366.

by J.B. Bird

First published June 5, 2005

Summary: From 1835-38, the Black Seminoles inspired and led the largest U.S. slave revolt. Here are the facts to prove it. Topics covered include:

- Comparison with other rebellions

- Classification: maroon war or slave rebellion?

- Plantation slaves in rebellion: 1835-38

- The fate of the plantation slaves

- The fate of the Black Seminoles

- Contrary perspectives: It was not a rebellion

- Contrary perspective No. 1: It was a wartime alliance

- Contrary perspective No. 2: It was collusion with maroons

Conclusion and final tally End notes and list of works cited

Note: When this essay was first published in June 2005, very few online or scholarly reference guides to slave rebellions cited the Black Seminole rebellion as a slave uprising and none cited it as the country's largest. Since then, thanks in part to this essay and website, more references correctly note the size of the Black Seminole slave rebellion, though many still omit it.

IntroductionLook at any standard reference to American slave revolts, and chances are, the Black Seminole rebellion of 1835-1838 does not even make the list. Below are some representative sites that can be readily checked online:[1]

The oversight is not unexpected given that the major scholars of American slavery, on whose writings the reference works rely, have likewise missed or misinterpreted the Black Seminole slave rebellion. According to John Hope Franklin, Eugene Genovese, Stanley Elkins, Kenneth Stampp, Herbert Aptheker, and the many scholars who have relied on these giants in the field, the Black Seminole maroons joined Indians to fight the U.S. Army in 1835, and some of the maroons may have been runaway slaves. But the scholars seem unaware that nearly 400 plantation slaves, and possibly hundreds more, joined the maroons and Indians in an uprising of slaves that had no peer for size and longevity in American history.

- Brittanica.com's entry under "slave rebellions."

- Chronology on the history of slavery and racism from The Holt House.

- Major revolts and escapes from AFRO-Americ@: Black resistance. [Resource no longer available online]

- Slave Revolts and Rebellions from The African-American: A Journey from Slavery to Freedom.

- A Chronology of Slave Actions in the United States from The Slave Rebellion Website, by Joseph Holloway.

- Slave Rebellions and Uprisings in the United States from the History Guy.

A section on Examples of scholarly oversight of the Black Seminole slave rebellion offers citations from the top scholars. For further confirmation of the oversight, one can also enter "slave rebellions" into any good search engine, or in the search function of a general black studies site like Africans in America. Or to be even more thorough, one can keyword search the leading academic journals on African American and U.S. history at Journal Storage online. Under "slave rebellions" or "slave revolts," many interesting articles will appear, but not a single one about the largest slave rebellion in American history.

The omission from mainstream history of both the Black Seminoles and the slave rebellion that they led is a curious phenomenon. The oversight is all the more interesting since the rebellion was not some obscure event that took place in a rural backwater, but rather a series of large-scale, disruptive escapes that occurred in conjunction with the largest Indian war in U.S. history and that resulted in a massive, well-documented destruction of personal property.[2]

The info in the table below can also be seen in this interactive map of major U.S. slave rebellions.

The reasons for the oversight are examined more thoroughly in the accompanying essay, "The buried history of the rebellion." This essay attempts to lay out the facts, making the case once and for all that the Black Seminole rebellion was the largest in U.S. history.

Depending on how one classifies the rebellion, in fact, it was not just the largest but may have been three or four times as large as its closest competitor. This renders the omission even more remarkable, if not downright suspicious.

Comparison with other rebellions

Below are the major American slave rebellions listed in chronological order.[3]

Year Rebellion Black Participants White deaths End result for the rebels 1712 New York City conspiracy 30-40 9 21 executed, 6 estimated suicides, 6 pardoned 1739 Stono rebellion 75-80 25 Estimated 50 killed & executed in suppression 1800 Gabriel Prosser's conspiracy 40[4] 0 35 executed, 4 escaped, 1 suicide 1811 Louisiana revolt 180-500 2 66 killed in battle, 16 executed, 17 escaped or dead 1822 Denmark Vesey's conspiracy 49[5] 0 49 condemned: 12 pardoned, 37 hanged 1831 Nat Turner's rebellion 70 57 20 conspirators executed including Turner, 100 or more blacks killed in mass reprisals 1835-38 Black Seminole rebellion, maroon & slave combined 935-1265 400[6] 500 emigrated west with Indians, 90 or more caught & re-enslaved, hundreds more surrendered to slavery, casualties unknown. 1835-38 Black Seminole rebellion, plantation slave only 385-465 N/A 90 or more caught & re-enslaved, hundreds surrendered and returned to slavery, uncertain number emigrated west with Black Seminoles. At least three of these are often mentioned as the largest or most significant in U.S. history: Nat Turner's rebellion, Denmark Vesey's conspiracy, and the Louisiana slave revolt of 1811.

Nat Turner's rebellion.

Scholars do not mention Turner's rebellion as the largest, but they often cite it as the most significant. Politically and socially, it probably was. For several months in 1831, the uprising and subsequent manhunt for Turner riveted national attention. In the wake of Turner's capture, trial, and execution, legislators across the country enacted tougher laws, severely tightening slave codes and clamping down on the rights of free Negroes. Conversely, the revolt fired the ideals of American abolitionists, helping lead the country down the long road to civil war.

The number of participants in the uprising was moderate in comparison with the larger rebellions, but the white casualties were high, which attested to the campaign's organization and violence.[7] To learn more about the uprising, you can visit the Web site Death and Liberty, which covers Virginia's three major slave insurrections during the 19th century.

Denmark Vesey's conspiracy

Vesey's conspiracy earned a nod as the largest rebellion in the 1999 book by David Robertson, Denmark Vesey: The Buried History Of America's Largest Slave Rebellion. The title was catchy, but the facts were off.

The conspiracy organized by Vesey, a 60-year-old free black carpenter in Charleston, South Carolina, was by all accounts both fascinating and politically significant. Aptheker gives an overview of the known facts in American Negro Slave Revolts (267-75), and you can find summaries online at Africans in America or The Atlantic Monthly issue from December 1999.

Vesey envisioned a massive uprising throughout Charleston and the surrounding areas, with rebel slaves receiving aid from St. Domingo. Reviewing the record, one can see why a writer was tempted to describe his rebellion as the largest in American history.

There's just one problem: Vesey's rebellion never materialized. The conspiracy unraveled when several slaves became informers, exposing the plot before it took place. Vesey and 130 slaves were immediately arrested as conspirators. Of these, 49 were ultimately convicted, with 37 being executed and 12 pardoned.

At the trials, witnesses testified that anywhere from 3,000 to 9,000 slaves were in on the plan. This was high drama, but in reality, scholars today have no idea how many people were involved in the conspiracy. The leaders allegedly recorded all of the names of their co-conspirators, but only a few such lists ever surfaced. Preparations must have been extensive, since the would-be rebels stashed away 250 pike heads and 300 daggers in anticipation of an uprising. No documentary evidence, however, points to the actual number of participants.[8]

Moreover, even if one accepts that thousands of slaves were in on the plot, none of these thousands ever rose in rebellion. Ultimately, only 49 were implicated -- in a conspiracy. On this basis, it is simply not credible to claim that Vesey's plot was the largest slave rebellion in American history. It might have been the largest plan, but even this can not be said with certainty.

Louisiana slave revolt.

This revolt is more often, and more credibly, described as the largest ever on U.S. territory. See, for example, the recent book American Uprising: The Untold Story of America's Largest Slave Revolt, by David Drummond, or the timeline entriy at The Slave Rebellion Website.

The known facts are minimal. On January 8, 1811, Charles Deslondes, a free mulatto from St. Domingo, led a body of slaves in a rebellion west of New Orleans along Louisiana's "German Coast." The slaves fought with cane knives and clubs before securing a few firearms. By January 11, local militia and army regulars had crushed the poorly armed rebels.

Aptheker reports that 82 blacks were killed or executed in the suppression of the revolt, with seventeen others either escaping or being left for dead. As a warning to future troublemakers, executioners placed the severed heads of sixteen black rebels on posts along the road leading to the plantation where the uprising started.[9]

If more facts were known, the Louisiana revolt might rival the Black Seminole rebellion in size, though certainly not in scope. The event was short-lived, and while it sent shockwaves around New Orleans, it never gained national attention. The rebel force must have been considerable, given that authorities sanctioned killing 82 of them. Reports placed the number of rebels at somewhere between 180 and 500. Aptheker estimated four or five hundred on uncertain authority, while Genovese was inclined toward the lower number.[10]

Unfortunately the only hard numbers associated with the revolt are the executed, dead, and missing, who totaled 99, far less than the documented participants in the Black Seminole rebellion.

Classification of the Black Seminole rebellion:

Maroon war or slave rebellion?Scholars who are not familiar with all the facts of the Florida slave uprising may object to comparing the Black Seminole rebellion with the actions listed above, on the grounds that the Black Seminoles waged a maroon war, which is different from an uprising of plantation slaves.

Were maroons the only black participants in the Florida uprising, this would be a valid point. Maroons were quasi-autonomous blacks, or "outliers," who lived on the fringes of slave society. Typically, maroons fought to retain the tenuous liberty that they already enjoyed, not to liberate themselves from oppressive masters.

Such was the case with a majority of the 500-800 Black Seminoles who rose in defiance against the United States in 1835. Though hundreds of these blacks were claimed by white citizens, most had long-standing ties to the Seminole Indians. Nominally, they were recognized as either free, quasi-free in comparison to plantation slaves, or at the very least, as established fugitives from white slavery. As such, the Black Seminoles technically waged a maroon war as opposed to a slave rebellion.

There are some interesting reasons to debate this classification, discussed at the end of this essay. The whole question, however, is irrelevant to the matter at hand. Regardless of whether the Black Seminoles were maroons or slaves, the facts show that they inspired the largest rebellion of slaves in U.S. history.

"Attack of the Seminoles on the block house." This hand-colored lithograph from the Gray & James series depicts one of the Seminoles' prolonged sieges of U.S. forces -- unusual for Indian warfare -- in April of 1836. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-11463.

Plantation slaves in rebellion, 1835-1838

This rebellion took place over 1835-38 and it involved plantation slaves in a classic uprising. The rebellion reached its peak in the first months of 1836, when hundreds of Florida slaves fled their plantations to join the Seminoles. White owners said that their slaves had been "captured" by Indians, but this was merely a gloss on circumstances that horrified the slaveholders. Indians did not capture the slaves. The slaves escaped.[11]

Planning for the mass defections had been underway for over a year. According to Kenneth Wiggins Porter, Black Seminole leaders made frequent visits to Florida's plantations throughout 1835, cementing ties to the field hands. When war erupted, hundreds of blacks fled to the Seminoles in an action that General Thomas Sydney Jesup described as a pre-arranged conspiracy:

"I have ascertained beyond any doubt, not only that a connection exists between a portion of the slave population and the Seminoles, but that there was, before the war commenced, an understanding that a considerable force should join on the first blow being struck."

Field slaves fought prominently in several early engagements. Many defectors painted their faces to signal their new allegiance. Urban and house slaves did their part as well, joining with free blacks from St. Augustine to help the Seminoles obtain critical supplies like powder and lead.[12]In the general uprising, blacks and Indians specifically targeted the sugar plantations along the St. John's River, west of St. Augustine. At the time these were some of the most developed plantations in all U.S. territory. Their destruction was swift and devastating. By February of 1836, less than two months into the war, the Seminole allies had destroyed 21 plantations. Where slavery and sugar mills once flourished, soldiers found smoking ruins and an industry laid waste.[13]

Before the uprising ran its course, at least 385 field slaves defected to the Seminoles. This number, derived from the escapes reported at the time in official military correspondence, newspaper reports, and claims on the government for damaged property, is conservative and probably low.[14] Two scholars who are among the foremost experts on slavery in the antebellum Florida, Canter Brown and Larry Rivers, speculate that there may have been as many as 750-1000 plantation rebels.[15] My own guess is that the numbers were higher than 385 but still close to this documented total.

The conservative number alone accounts for the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history. Regardless of whether or not the Black Seminoles are counted as participants -- and regardless of academic conventions -- the facts show that they inspired an uprising that easily eclipsed all other American slave rebellions.

Curiously, this overlooked rebellion enjoys yet another distinction -- it was not a complete failure.

Was the rebellion a success?The answer to this question hinges on the combined fates of the plantation slaves and the Black Seminoles themselves.

The fate of the plantation slaves

What happened to the 385-plus plantation slaves who joined the Seminoles? Unfortunately, we know of their fate only in general details. According to Porter, after a year or more of life in the swamps, a majority of the defectors surrendered and returned to chattel slavery. As they came in, some spoke of ill treatment at the hands of the Seminoles, though witnesses at the time thought that these complaints were mainly efforts to win back the sympathy of white masters.[16]

Not all of the plantation slaves surrendered. The Army captured at least 93 who were known to be the property of white citizens.[17] These captured slaves were reportedly returned to their owners.[18]

Another small segment of plantation rebels subsumed themselves within the ranks of the Black Seminoles. Field slaves at the outset of the war, these courageous blacks ultimately won their liberty when General Jesup agreed to let them emigrate west with the established "Indian Negroes" (the Black Seminoles) in 1837 and 1838. At least five such field slaves surrendered under Jesup's promise of freedom at the close of 1837.[19] Quite likely dozens more availed themselves of this option, but there are no hard numbers to go by.

Some plantation slaves may also have succeeded in feigning status as established "Indian Negroes." By the close of 1837, the Army was anxious to move the most militant blacks west, regardless of whether they were Indian maroons or the property of white citizens. Lt. Sprague defended this policy on pragmatic grounds:

"The negroes ... have, for their numbers, been the most formidable foe, more bloodthirsty, active, and revengeful, than the Indians .... The negro, returned to his original owner, might have remained a few days, when he again would have fled to the swamps, more vindictive than ever.... Ten resolute negroes, with a knowledge of the country, are sufficient to desolate the frontier, from one extent to the other."[20]

In this frequently quoted passage, Sprague was defending a policy that was controversial among slaveholders. From the start, Florida slaveholders had demanded the return of all blacks who were claimed by white owners. In 1837, the Army's decision to yield on this policy seemed to confirm that a portion of the plantation rebels had succeeded in winning their freedom.Even after the Army's policy reversal, some blacks remained in the wilderness, fighting alongside Coacoochee and other Seminole Indian chiefs from 1838-42.[21] Quite likely, these final holdouts were plantation rebels, since most of the Black Seminole militants had surrendered with or before John Horse in 1838.

So, what can we conclude about the success of the rebellion?

As far as the plantation slaves were concerned, the Florida rebellion was a failure, since a majority of the rebels returned to chattel slavery. The uprising was not, however, a total disaster -- at least not in comparison with the other major U.S. rebellions, which all ended in violent repression. In Florida, history leaves no record of mass reprisals against the rebels. There were no heads placed on pikes, as occurred in Louisiana, and no mass trials and executions, as took place after the failed conspiracies of Prosser and Vesey. Rather, white Floridians seem to have gratefully accepted the return of their slaves.

In the wake of the uprising, the territorial legislature did pass tougher slave codes and more draconian laws aimed at free blacks. Yet even these laws were deceptive. As Brown reveals in his essay on territorial race relations, Florida's slave laws tended to set strict standards that individual whites largely ignored, choosing instead to negotiate more lenient relations with their bondsmen.[22]

Though most of the 385-plus plantation rebels failed to win freedom, a small minority succeeded. Unfortunately, without further research the number in this category cannot be known -- and will probably never be known with anything close to certainty.

What about the fate of the Black Seminoles?

If the plantation rebels largely failed, the Black Seminoles enjoyed a converse fate. As a community, they won a limited but substantial victory when General Jesup reversed U.S. policy, promising freedom to all black warriors who surrendered over the winter and spring of 1837-38.

Only later, in the Indian Territory, would the limitations of Jesup's promise become apparent, leading to dire problems for many Black Seminoles. In 1838, however, Jesup's promise appeared valid. By his own admission, the general had offered "the most liberal terms." The leaders of the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history appeared to have won a conditional victory.[23]

True, they were not allowed to remain in Florida, which had been the Seminoles' stated objective all along. For the black warriors, however, liberty had always been the true objective, wherever it was offered.

In the end, 500 blacks -- mainly Black Seminoles, with some plantation rebels mixed in -- emigrated west to the Indian Territory. The blacks emigrated under a tangled web of legal and social arrangements. Roughly speaking, half of them went west under Army promises of freedom, and half emigrated under traditional, private arrangements with Seminole Indian masters.[24]

Contrary perspectives: It was not a rebellionAmong contemporary academics, oversight of the Black Seminole-led slave rebellion has resulted largely from a lack of awareness of the details of the rebellion, as can be seen in the section of examples of scholarly oversight. From Aptheker (1943) to Franklin (1999), the seminal writers on American slave resistance have been aware of the Black Seminole maroon uprising but unclear or entirely unaware of the mass participation of plantation slaves that took place in conjunction with the maroon and Indian conflict.

While this lack of awareness accounts for the persistence of the oversight, some academics have, or will, argue that the events in Florida were not, in fact, a slave rebellion. Academic convention is very strong. No doubt some academics, finding it inconceivable that they have not already read about the Florida slave rebellion, will seek out reasons to declare it was not a true slave rebellion, based on a variety of definitions.

Contrary perspective No. 1: It was a wartime alliance

Andrew Frank, an historian at California State University, Los Angeles, made an argument along these lines in his review of Larry Rivers' Slavery in Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000). Rivers, along with Canter Brown, is one of only two scholars to suggest that the Second Seminole War "probably constituted the largest slave uprising in the annals of North American history" (Rivers, 219). In a review published online by H-Net Reviews in May 2002, Frank takes issue with Rivers for being too liberal in defining his terms:

Rivers effectively demonstrates the participation of hundreds of fugitive slaves and black Seminoles, who he states were still maroons, in the war. Rivers chooses not to challenge the conventional definition of slave rebellion, however, in this discussion. Instead, he stresses that the historian's neglect to understand the war as a slave rebellion is compounded by its relatively large number of enslaved participants. This needs further explanation. Any definition of "slave uprising" that includes the Second Seminole War would also include, at the very least, the American Revolution, War of 1812, and American Civil War.

Frank raises an important point: a slave rebellion is defined as an armed uprising of slaves, but is it a rebellion if it takes place within the context of an organized war? The answer to the question is especially thorny in the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the U.S. Civil War. Some scholars have described elements of the black role in these conflicts as slave rebellion, but given the role played by organized state powers, it is problematic to claim that the participation of all slaves in the conflicts constituted open revolt. During the Second Seminole War, however, the acts of mass slave resistance were far more autonomous and self-determined than the black resistance in the other three conflicts and in fact corresponded almost perfectly to the scholarly definition of the New World slave revolt. A review of the role of slaves in each conflict highlights the distinction.

In the case of the American Revolution and the War of 1812, slaves sought freedom based on promises of safe haven from a foreign government. The British used such promises to lure more than 10,000 slaves from the American colonies during the Revolution. They deployed the tactic again in the War of 1812, attracting several thousand American slaves who sought refuge in the British lines. After both conflicts the British made good on their promises of safe haven. Following the Revolution, many black loyalists were settled in Canada. After the War of 1812, the British settled black refugees in Canada, Trinidad, and other parts of the Caribbean. British support for rebel slaves during the War of 1812 was so steadfast, in fact, that it created a bitter dispute with the U.S. after the war. The Treaty of Ghent included a clause demanding return of American slaves who had defected. The British refused to comply with the provision, and the matter was only resolved in 1824 when Americans agreed to accept financial compensation for their human property.

The war between the states featured a similar dynamic, with the difference that the slaves themselves played the lead role, in far greater numbers, in the defection to the "foreign power" (here the North) that took place. More than 90,000 southern slaves sought safe haven in the northern lines during the U.S. Civil War. Initially, their actions precipitated intense debates among northerners as to how to deal with this living property of the enemy, called "contrabands" of war. While generals like John C. Fremont clamored to arm the rebels and declare them free, President Abraham Lincoln was initially reluctant. Lincoln had publicly stated that the country was waging war to restore the union, not to end slavery, and he hesitated to appropriate the slave property of the South, for fear it would change the nature of the conflict. Ultimately, with the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, Lincoln bowed to the arguments of his generals and offered freedom to the southern contrabands and all slaves in confederate areas. The reasoning behind this change of policy was based in part on the precedent of the Black Seminoles, as Rebellion documents, who had furnished an example of the federal government's right to liberate rebellious slaves during wartime.

The slave resistance in Florida from 1835-1838 was distinct from the slave defections in these other three wars. First and foremost, no foreign power offered safe haven to the slaves who rebelled in Florida in 1835. There is no record that the small Seminole Nation made such an offer, and the nation—fighting for its very existence and homeland—was not in a position to fulfill any such promises had they been offered. The British in 1776 and 1812 offered full liberty, land, and citizenship rights in promises backed by one of the world's foremost powers; and the British made good on their promises. The example of the Civil War is a bit more complicated, because slaves themselves initiated much of the policy debate by defecting in droves to the North; nonetheless, the safe haven that defecting slaves ultimately found under the auspices of the Union Army was categorically distinct from the self-determination-amid-chaos that rebel slaves pursued in Florida.

The role of the slaves in planning resistance and their motives for resistance were two more distinguishing factors of the Black Seminole slave rebellion. In the Revolution and the War of 1812, the British planned the wars. Their offers of freedom to slaves were strategic tactics to disrupt the enemy. In Florida in 1835, in contrast, U.S. military officials determined that slaves had themselves conspired with the Black Seminole maroons to plan the mass uprising and wholesale destruction of sugar plantations at the outset of the war. The slaves were not motivated by a tactical offer of freedom from a foreign power. Rather, they fought with the idea, according to military leaders, of winning transport to freedom in Cuba. In other words, the Florida slaves of their own accord helped plan the conflict, then helped overthrow their masters and destroy their property while joining a mass uprising with the hope of winning freedom by force of arms. This is distinct from the defections to a major state power that took place during the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and even the U.S. Civil War.

Contrary perspective No. 2: It was collusion with maroons

In accepting that the Florida uprising was a slave rebellion, some academics might raise another consideration as grounds for exclusion: the fact that the slaves colluded with maroons. Doesn't this collusion exclude the uprising from the realm of a slave rebellion? The slaves may not have had the protection of a foreign power, this line of reasoning would say, but they benefited from the promised protection of their maroon and even Indian co-conspirators, and this protection rendered their actions more akin to a military alliance than a slave revolt.

This argument only works if scholars are ready to throw out the entire New World history—and accepted scholarly definition—of slave rebellions. The leading scholars of New World slave resistance, from Eugene Genovese to Orlando Patterson, have routinely pointed out the central role of maroons in the region's major rebellions. "The most impressive slave revolts in the hemisphere," wrote Genovese, "proceeded in alliance with maroons or took place in periods in which maroon activity was directly undermining the slave regime or inspiring the slaves by example" (From Rebellion to Revolution 33). Maroon-slave alliances were rarely harmonious, however, since the interests of slaves and maroons often conflicted:

The relationship between maroons and slaves was complex and by no means always friendly. The peace treaties between the maroons and white regimes usually provided for black autonomy in return for military support against slave revolts and for the return of new runaways. But the existence of militarily respected maroon colonies destroyed in a single stroke the more extravagant racist pretensions of the whites and provided a beacon to spirited slaves. (Genovese From Rebellion to Revolution 591)

The rebellion in Florida corresponded faithfully to the pattern of maroon-slave alliances that Genovese described in Jamaica, Surinam, and Brazil. As in those countries, in Florida the maroons (Black Seminoles) initially sought a strategic alliance with rebellious slaves. Ultimately, however, the maroons agreed to surrender in exchange for white recognition of their autonomy. In Florida, the U.S. Army acknowledged maroon autonomy by offering promises of freedom to 250 Black Seminoles and giving secure passage to 500 of them, allowing them to travel west under their traditional arrangements with the Seminole Indians. At the same time that the maroons were negotiating safe passage to the west, the majority of Florida's plantation slave rebels were surrendering and being returned to their owners. This coincidence did not exactly equal "military support against slave revolts" on the part of the Black Seminoles, but it showed that the Black Seminoles' communal interests were not synonymous with the freedom of the plantation rebels.

Florida's plantation rebels did, however, fare more successfully than slaves in other joint maroon-slave revolts. In fact they may have been the most successful slave rebels in the New World outside of Haiti. Admittedly, this is not a high standard, given the dismal record of New World slave revolts. Still, it was notable that as the rebellion in Florida wound down, the Black Seminole maroons did not actively round up plantation rebels, as occurred at the end of other maroon wars. In Florida, slaves also were not executed in reprisal for the rebellion, something which happened after all of the other major U.S. slave revolts and conspiracies, from the New York City revolt of 1712 to Nat Turner's rebellion in 1831 and even John Brown's raid in 1859. The comparative leniency after the Black Seminole slave rebellion reflected several factors, including Florida's more tolerant and complex approach to slavery, inherited from the Spanish, and the extended, wartime nature of the revolt. By 1838, slaveholders living on Florida's sparsely populated frontier also desperately needed the labor of their bondsmen, which was surely an inducement to clemency.

One fact above all else, however, demonstrates the comparative success of Florida's plantation slave rebels: military records show that at least a small contingent of five to ten plantation slaves were allowed to go west with the Black Seminole maroons. The number of slaves who won freedom by this means may have been much higher, but it is not likely that research will reveal the true number, because during the emigration negotiations, the military made no effort to carefully distinguish maroons from slaves. The military did not want the number of slaves sent west to become known, for fear of upsetting Florida slaveholders. In the spring of 1837, slaveholders helped reignite the war on this very point. The officer corps deeply resented this citizen interference and sought to avoid its repetition.

With this in mind, it is instructive to read an oft-cited passage from John T. Sprague's 1848 history of the war. Writers typically use the passage, in which Sprague described the black warriors as "the most formidable foe, more blood thirsty, active, and revengeful, than the Indians," to demonstrate the key role that the Black Seminoles played during the Second Seminole War. Read at greater length and in proper context, however, the passage reveals another important point: members of the U.S. Army were defensive even in 1848 about having granted freedom to rebellious blacks—freedom not just to maroons, who were already comparatively free, but also to plantation slaves, who had taken up arms against the oppressor. Sprague couched the incendiary fact in suitably euphemistic prose—it was plain to see for those who understood the subject but opaque to those who did not. Sprague was an authority on the war, having served in Florida intermittently from 1835 on under several commanding generals, including his father-in-law, General William Worth. It was Worth who personally reaffirmed the freedom of the Black Seminole maroon leader John Horse and, more notoriously, allowed recent plantation rebels to emigrate west with the Seminoles. The army policy of sending rebellious slaves west was controversial with white and Creek Indian slaveholders. Worth defended his actions by saying that he did not want the swamps of Florida to become "the resort of runaways" (Worth cited in Porter Negro on the American Frontier 257).

With this in mind, Sprague's description of the "formidable" black warriors takes on a new dimension. An astute reader can hear that his description was not just an explanation of recent history but was also a spirited defense of his father-in-law's controversial army policy:

The Negroes from the commencement of the Florida War, have, for their numbers, been the most formidable foe, more blood thirsty, active, and revengeful, than the Indians….The lives of citizens and their property, demanded that they should be sent far beyond the country with which they are familiar…. The swamps and hammocks of Florida could, for years, be made safe retreats from bondage, where without labor or expense, they might defy the efforts of armed men…. Ten resolute Negroes, with a knowledge of the country, are sufficient to desolate the frontier, from one extent to the other. To obviate all difficulty, the claimant of the Negro in possession of the Indian, was, upon identifying and proving property, paid a fair equivalent, determined by a board of officers. (Sprague Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War 306)

The incendiary revelation was that "claimants of the Negro in possession of the Indian" were paid for their property, provided they could show the validity of their claim. This meant that the government was not just shipping quasi-free maroons to the west but also slaves—that is, black rebels identified as property of white claimants. In defending this policy, Sprague echoed the thoughts of Generals Worth, Thomas Sydney Jesup, Edmund Pendleton Gaines and other leading officers of the war who felt that rebellious slaves had to be shipped west for the good of the country.

This policy contravened the initial goals of President Andrew Jackson and Secretary of War Lewis Cass, who in 1836 ordered that the Florida war be prosecuted until every "living slave belonging to a white man" was returned. Officers in the field, confronting the reality of an intractable conflict, reversed this policy. In the end, the officers concluded that distinguishing maroons from slaves was less important than simply brokering peace with the most militant black elements.

While the total number of plantation rebels shipped west with the Black Seminole maroons will likely never be known, the fact remains that even if the army only allowed five or ten plantation rebels to go west, the concession stands as the sole example in U.S. history of slaves succeeding in a rebellion from chattel slavery. It may be one of the only examples in the history of the New World. Scholars, for example, generally regard the Haitian revolution of 1804 as the only example of a successful rebellion against New World chattel slavery.

That a handful of slaves won their freedom through force of arms was a remarkable accomplishment. Given its implications for the slaves of the south, it comes as no surprise that slaveholders buried it deep. How historians missed the accomplishment is another question.

Regardless of success or failure, a slave rebellion is defined by the circumstances of its inception. At the outset of the uprising in Florida in 1835, the largest body of rebel slaves in U.S. history rose with the motive of winning freedom through self-directed flight from American shores. It would seem petty to say today that their actions were not a slave rebellion simply because news of it comes as a surprise to some scholars.

Conclusion and final tallyTo tally the final numbers of the Black Seminole rebellion, one has to decide how to classify the conflict. One can safely describe it as a maroon war (the only one in American history) that inspired the country's largest slave rebellion. The numbers break down as follows:

Maroon rebels (Black Seminoles) 500-800 Plantation slaves in revolt 385-465 Total black rebels 935-1265 This leads to a conservative tally of 385 slaves in rebellion.[25] One can go further, making a case that all of the blacks who resisted the U.S. in Florida were rebellious slaves. Certainly many white residents of Florida characterized the Black Seminoles as such during the 1830s. In 1848, the U.S. Attorney General added his voice to the debate when he ruled that legally the Seminole maroons in Florida had been slaves in revolt.[26] This decision, motivated by southern political interests, was devastating to the Black Seminoles. Within a year it led John Horse and his immediate followers to seek freedom in Mexico.

If the U.S. Attorney General believed that the Black Seminoles were slaves in revolt, then historians can surely at least contemplate according them like status, accepting that the maroons might not just have inspired the largest slave rebellion in American history, they may have participated in it as well. Such a conclusion brings the total number of rebels to 935 or more. It would be somewhat ironic if academics today were to strip the Black Seminoles of their status as rebellious slaves, 150 years after American politicians tried to crucify them with the same distinction.

See complete list of works cited for more information on individual sources.

[1] Most of these sites are based on the leading academic sources on American slave revolts, Herbert Aptheker's American Negro Slave Revolts (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943) and Eugene Genovese's From Rebellion to Revolution (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979). Other works are useful, but the vast majority of contemporary references to slave rebellions draw on these two. Lerone Bennett's Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America (New York: Penguin, 1984) is also popular. Return to text.

[2] Kenneth Wiggins Porter's Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People (edited by Thomas Senter and Alcione Amos, Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1996) offers the definitive description of the black role in the Second Seminole War. For additional details, see Mark Frederick Boyd, “The Seminole War: Its Background and Onset,” Florida Historical Quarterly 30.1 (July 1951): 3-115. Return to text.

[3]Sources on the first six rebellions are Aptheker and Genovese. On the Black Seminole slave rebellion, the estimate of 385 plantation-slave rebels is original to this work. See the tally of plantation slaves in the Black Seminole slave rebellion for the number's derivation and more detail on the sources, or see the complete essay on the rebellion.

Sources from the period used to derive the number of slave participants in the Black Seminole slave rebellion:Secondary sources referring to number of participants in the rebellion:

- Cohen, Myer M. Notices of Florida and the Campaigns. 1836. Intro. O.Z. Tyler, Jr. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1964: 81, 88, 141, 141ff.

- Niles' Weekly Register 49.22 (January 30, 1836): 368-370.

- Florida Herald, January 13, 1836, as cited in Jacob Rhett Motte, Journey into Wilderness: An Army Surgeon’s Account of Life in Camp and Field During the Creek and Seminole Wars, 1836-38. Ed. James F. Sunderman. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1953: 277-278ff.

- Sprague, John T. The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War. New York: D. Appleton, 1848: 106.

- United States Congress. American State Papers: Military Affairs. 7 vols. Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832-1860. 6: 21-22, citing Saint Augustine Herald, January 13, 1836.

- United States Congress. House. "Joseph M. Hernandez. (To accompany Bill H.R. No. 877.) July 6, 1838." 25 Congress, 2 Session, Report 1043: 2.

- United States Congress. House. 25 Congress, 3 Session, Ex. Doc. 225: 106.

- Boyd, Mark Frederick. “The Seminole War: Its Background and Onset.” Florida Historical Quarterly 30.1 (July 1951): 63.

- Brown, Canter. "Race Relations in Territorial Florida, 1821-1845,” Florida Historical Quarterly 73.3 (January 1995): 289, 304 on the same topic.

- Littlefield, Daniel F. Africans and Seminoles. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977: 36-37.

- Rivers, Larry Eugene. Slavery in Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000: 203.

[4] Number punished for conspiracy. Return to text.

[5] Number punished for conspiracy. Return to text.

[6] Estimate based on casualty numbers. At least 1590 white soldiers died in the conflict. The Black Seminoles and their slave allies constituted approximately 25% of the Seminole alliance, so .25 * 1590 = 398, or an estimate of 400. Return to text.

[7] Aptheker 293-307. Return to text.

[8] Aptheker 272. Return to text.

[9] Aptheker 249-51, Bell 46. Return to text.

[10] Genovese 43. Return to text.

[11] Sprague Origin 106, Boyd "Seminole" 65-66, Rivers 203. Return to text.

[12] Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. The Negro on the American Frontier. New York: Arno Press, 1971: 266-75. Brown "Race" 304. Jesup quoted in John Hope Franklin's Runaway slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999): 87-88. Return to text.

[13] See "A Sugar Empire Dissolves" in Boyd "Seminole" 58-69. Return to text.

[14] The number is original to this essay. For information on its derivation, see tally of plantation slaves in the Black Seminole slave rebellion. Return to text.

[15] Brown "Race" 304, Rivers 203. Return to text.

[16] Motte 116, Mahon 205, Porter Negro 252-53, 278-79. Return to text.

[17] American State Papers: Military Affairs 7: 852. Return to text.

[18] Giddings 155. Return to text.

[19] Porter Negro 255. Return to text.

[20] Sprague Origin 309. Return to text.

[21] Eighteen blacks, for instance, were reportedly allied with Coacoochee after 1838. Porter Negro 259. Return to text.

[22] See Brown, "Race Relations in Territorial Florida: 1821-1845," which concludes (307) that where race relations were concerned, Florida law "often overreached community consensus and, if not challenged directly, was ignored or treated indifferently by a broad range of residents -- white and black, slave and free. Day-to-day life in Florida continued to offer far greater possibilities for many of the territory's residents than the letter of the law seemingly permitted." Return to text.

[23] American State Papers: Military Affairs 7: 834, Mahon 200, Genovese 73, and Bruce Edward Twyman, The Black Seminole Legacy and Northern American Politics, 1693-1845 (Washington: Howard University Press, 1999). Return to text.

[24] Littlefield Seminole 15-36 offers the best accounting so far of the complicated and varied circumstances under which the Black Seminoles emigrated west, including appendices of the government lists of Indians and negroes sent west over the period. Return to text.

[25] For complete sources and explanation of how the number of plantation slaves was derived, see the tally of plantation slaves in the Black Seminole slave rebellion in the toolkit on the rebellion. For a list of sources only, see end note 3 above. Return to text.

[26] For more on this dramatic legal decision, see the related segment, American Justice, in part three of the trail narrative . Return to text.