The Trail of Tears is an epochal moment not only in Cherokee history, but also in Black history.

Editor's Note: Tiya Miles is chairwoman of the Department of Afro-American and African Studies, and professor of history and Native American studies at the University of Michigan. She is the author of "Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom" and "The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story." She is also the winner of a 2011 "genius grant" from the MacArthur Foundation.

By Tiya Miles, Special to CNN

(CNN) – African American history, as it is often told, includes two monumental migration stories: the forced exodus of Africans to the Americas during the brutal Middle Passage of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, and the voluntary migration of Black residents who moved from southern farms and towns to northern cities in the early 1900s in search of “the warmth of other suns.” A third African-American migration story–just as epic, just as grave–hovers outside the familiar frame of our historical consciousness. The iconic tragedy of Indian Removal: the Cherokee Trail of Tears that relocated thousands of Cherokees to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), was also a Black migration. Slaves of Cherokees walked this trail along with their Indian owners.

In 1838, the U.S. military and Georgia militia expelled Cherokees from their homeland with little regard for Cherokee dignity or life. Families were rousted out of their cabins and directed at gunpoint by soldiers. Forced to leave most of their possessions behind, they witnessed white Georgians taking ownership of their cabins, looting and burning once cherished objects. Cherokees were loaded into “stockades” until the appointed time of their departure, when they were divided into thirteen groups of nearly 1,000 people, each with two appointed leaders. The travelers set out on multiple routes to cross Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas at 10 miles a day with meager supplies.

At points along the way, the straggling bands were charged fees by white farmers to cross privately owned land. The few wagons available were used to carry the sick, infant, and elderly. Most walked through the fall and into the harsh winter months, suffering the continual deaths of loved ones to cold, disease, and accident. Among these sojourners were African Americans and Cherokees of African descent. They, like thousands of other Cherokees, arrived in Indian Country in 1839 broken, depleted, and destitute.

In addition to bearing the physical and emotional hardships of the trip, enslaved Blacks were enlisted to labor for Cherokees along the way; they hunted, chopped wood, nursed the sick, washed clothes, prepared the meals, guarded the camps at night, and hiked ahead to remove obstructions from the roads.

One Cherokee man, Nathaniel Willis, remembered in the 1930s that: “My grandparents were helped and protected by very faithful Negro slaves who . . . went ahead of the wagons and killed any wild beast who came along.” Nearly 4,000 Cherokees died during the eviction, as did an unaccounted for number of Blacks. As one former slave of Cherokees, Eliza Whitmire, said in the 1930s: “The weeks that followed General Scott’s order to remove the Cherokees were filled with horror and suffering for the unfortunate Cherokees and their slaves.”

Although Black presence on the Trail of Tears is a documented historical fact, many have willed it into forgetfulness.

Some African Americans avoid confronting the painful reality of Native American slave ownership, preferring instead to fondly imagine any Indian ancestor in the family tree and to picture all Indian communities in the South as safe havens for runaway slaves.

Some Cherokee citizens and Native people of other removed slaveholding tribes (Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles) have also denied this history, desiring to cordon off forced removal as an atrocious wrong that affected only Native Americans. By excluding Blacks (many of whom had Native “blood”) from a claim on this history, these deniers also seek to expel the descendants of Freedmen and women from the circle of tribal belonging. For it is the memory of this collective tragedy, perhaps more than any other, that binds together Cherokees who draw strength from having survived it.

As a researcher whose work focuses on African-American and Native American histories, I have encountered this resistance. A few years ago, I spoke on the subject of Blacks in the Cherokee removal at a conference of the National Trail of Tears Association. One member of the audience, a Cherokee instructor of Cherokee history, insisted that this was an historical event only for Cherokees, a story that rightfully belonged to them alone. This is a view shared by a former principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, who reportedly implied in a published remark that descendants of Freedpeople do not deserve tribal rights because they did not suffer the collective trauma of removal. The Trail of Tears is a sacred story to the Cherokees, as in special and set apart. It carries a meaningful lesson across time and space—about greed, injustice, and the perseverance of a people staring into a bleak and unknown future. However, a potent story shared with others is not necessarily diminished by the sharing; it might instead grow stronger in its ability to enlighten.

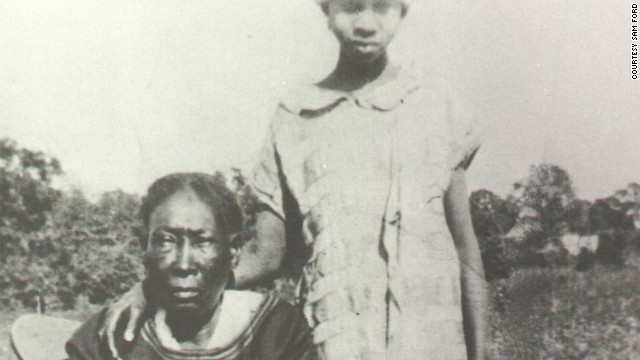

For Black History Month, I collected the opinions of individuals rarely asked about their view of the Trail of Tears: descendants of slaves owned by Cherokees. Common themes in the responses I received were pain at having their history publicly denied and pride in their ancestors’ ability to survive multiple trials.

Kenneth Cooper, a Cherokee Freedmen descendant and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who has researched his family history through oral and documentary methods, has a great-great-great grandfather, Thomas Still, who walked the Trail of Tears. Cooper said, “At least one of my ancestors was on the Trail of Tears—by double compulsion. The U.S. troops compelled his mixed-white Cherokee owner, who compelled my ancestor to come and, presumably, provide for his needs.”

Terry Ligon, a descendant of Choctaw and Chickasaw slaves who writes a blog about the topic, was frustrated because “the typical story about the ‘Trails of Tears’ speaks to the horrors of uprooting ‘Native Americans’ from their homes...[while] the story that rarely gets told is the tears shed by people of African descent who were enslaved within these same tribes of ‘Native Americans.’”

Olon Dotson, a professor of Architecture at Ball State University, said his great-great-great- grandmother, Betty Mantooth Teichmann Childers Starks, was born to an enslaved woman en route on the Trail of Tears. When Dotson found out about this hidden chapter of his family’s history, he felt “angered and betrayed,” and his anger was not only directed at Indians. “The feeling of betrayal,” he said, “was derived from the customary portrait of American history, as taught and understood, which paints the Five Civilized Tribes merely as victims of cruel and racist policies with little or no mention of the African American experience in the context. I was prepared to pounce on any African American who felt compelled to express pride in their Native American heritage at the expense of their African blood.”

Some descendants expressed no outrage, but simply wanted the experience of their ancestors to be remembered and respected. Olive Anderson, a descendant of slaves owned by the Cherokee Vann and Bean families, feels proud of her ancestors’ bravery, both during Removal and the Civil War, when her great great grandfather, Rufus Vann, fought with the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers. “Let it be known,” she said, “that our ancestors walked, fought, loved and died to make this country what it is today.”

The Trail of Tears is an epochal moment not only in Cherokee history, but also in Black history. Descendants of slaves owned by Native people therefore claim this story as rightful heirs. Kenneth Cooper concluded in his remarks to me: “I don’t see how Cherokees...can separate the history of the tribe from the history of the Freedmen; they are irrevocably intertwined, before, during, and after the Trail of Tears.” The intertwined histories of Freedpeople and Cherokees, of African American history and Native American history, of all groups in this great and varied nation of ours, is a historical reality that may prove to be one of our greatest strengths.

The opinions expressed are solely those of Tiya Miles.