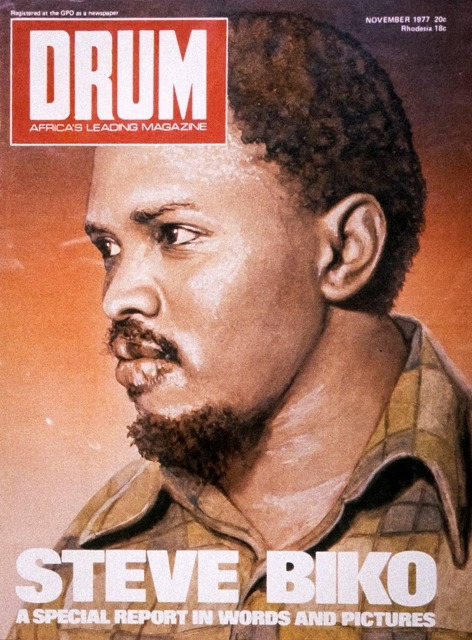

Steve Biko on a 1977 cover of DRUM Magazine as part of a special report into his life and death whilst in police custody.

__________________________

STEVE BIKO DOCUMENTARY

Life and Death of Steve Biko (Full Documentary)

This documentary gives you a look at who Steve Biko was and what he meant to the revolution against apartheid in South Africa.

Steve Biko was the founder of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa. In 1968 he cofounded the all-black South African Students’ Organization.The organization’s message spread from campuses to the general community, and in 1972 Biko helped found the Black People’s Convention. He was arrested many times for his anti-apartheid work and in 1977, died from injuries while in police custody.

>via: http://dynamicafrica.tumblr.com/post/31384871279/life-and-death-of-steve-biko...

__________________________

September 12th marks the anniversary of the death of one of South Africa’s most prolific and pioneering anti-Apartheid activists, Stephen Bantu Biko.

Biko rose to prominence as a student leader whilst at university, establishing the all-black and pro-black South African Students Organisation (SASO). He later became the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) in the early 70s, an ideological revolution aimed at the uplifting of black culture in the face of the systematic and racially oppressive system that was Apartheid.

The growth of the BCM threatened the structure of Apartheid so much so that in 1973 Biko was banned, by the South African government, from taking part in any political activity and was confined to the magisterial district of King William’s Town, his birth place.

In spite of being banned, Biko continued to advance the work of Black Consciousness. For instance, he established an Eastern Cape branch of BCP and through BCP he organised literacy and dressmaking classes and health education programmes. Quite significantly, he set up a health clinic outside King William’s Town for poor rural Blacks who battled to access city hospitals.

In the wake of the urban revolt of 1976 and with the prospects of national revolution becoming increasingly real, security police detained Biko, the outspoken student leader, on August 18th. At this time Biko had begun studying law by mail through the University of South Africa/UNISA. He was thirty years old and was reportedly extremely fit when arrested. He was taken to Port Elizabeth but was later transferred to Pretoria where he died in detention under mysterious circumstances in 1977.

Due to local and international outcry his death prompted an inquest which at first did not adequately reveal the circumstances surrounding his death. Police alleged that he died from a hunger strike and independent sources said he was brutally murdered by police. Although his death was attributed to “a prison accident,” evidence presented during the 15-day inquest into Biko’s death revealed otherwise. During his detention in a Port Elizabeth police cell he had been chained to a grill at night and left to lie in urine-soaked blankets. He had been stripped naked and kept in leg-irons for 48 hours in his cell. A blow in a scuffle with security police led to him suffering brain damage by the time he was driven naked and manacled in the back of a police van to Pretoria, where, on 12 September 1977 he died.

Two years later a South African Medical and Dental Council (SAMDC) disciplinary committee found there was no prima facie case against the two doctors who had treated Biko shortly before his death. Dissatisfied doctors, seeking another inquiry into the role of the medical authorities who had treated Biko shortly before his death, presented a petition to the SAMDC in February 1982, but this was rejected on the grounds that no new evidence had come to light. Biko’s death caught the attention of the international community, which increased the pressure on the South African government to abolish its detention policies and called for an international probe on the cause of his death. Even close allies of South Africa, Britain and the United States of America, expressed deep concern about the death of Biko. They also joined the increasing demand for an international probe.

It took eight years and intense pressure before the South African Medical Council took disciplinary action. On 30 January, 1985, the Pretoria Supreme Court ordered the SAMDC to hold an inquiry into the conduct of the two doctors who treated Steve Biko during the five days before he died. Judge President of the Transvaal, Justice W G Boshoff, said in a landmark judgment that there was prima facie evidence of improper or disgraceful conduct on the part of the “Biko” doctors in a professional respect. This serves to illustrate that so many years after Biko’s death his influence lived on.

He is survived by his two sons.