James Bain

May 21st, 2012

May 21st, 2012More than 2,000 people have been exonerated of serious crimes since 1989 in the United States, according to a report by college researchers who have established the first national registry of exonerations.

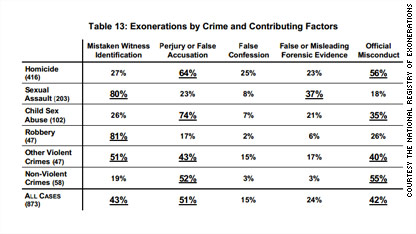

Researchers say their registry is the largest database of these types of cases and showcases some of the major issues with the criminal justice system, including that the leading causes of wrongful convictions are perjury, faulty witness identification and misconduct by prosecutors.

"No matter how tragic they are, even 2,000 exonerations over 23 years is a tiny number in a country with 2.3 million people in prisons and jails," says a report released by the authors. "If that were the extent of the problem we would be encouraged by these numbers. But it’s not. These cases merely point to a much larger number of tragedies that we do not know about."

Read the report (PDF) | Exonerations by state and county (PDF)

The registry itself, which looks deeply into 873 specific cases of wrongful conviction, examined cases based on court documents as well as from groups that have long documented wrongful convictions. That group of wrongfully convicted spent more than 10,000 total years in prison, according to the report, with an average of 11 years each.

Many of the cases of the wrongfully accused were championed by the Innocence Project, a well-known group that works with many inmates to try to clear their names based on DNA evidence. The group has documented 289 post-conviction DNA exonerations. The earliest came in 1989, when DNA testing was being heavily used to re-examine cases for the first time.

The database is a fully searchable list of those who were convicted, broken down by their crimes, sentences and reason for exoneration. Some go into extensive detail about the long and treacherous roads to exoneration that prisoners have undergone.

James Bain is the longest-serving prisoner to be exonerated by DNA evidence, spending 35 years behind bars for a crime he didn't commit. He was convicted in 1974, at age 19, of kidnapping and raping a 9-year-old boy in Lake Wales, Florida.

His life was returned to him in December 2009, when a Florida judge freed him after DNA testing proved he did not commit the crime.

"Bain’s photo was included in a lineup of five photographs, and the victim picked Bain as his attacker. Based on the identification and little else, Bain was convicted and sentenced to life in prison," according to the database. "Bain had no criminal record at the time of his arrest, and insisted he was at home watching television with his sister when the crime occurred."

In the backyard of his mother's home in Tampa, Bain stood among grapefruit and orange trees that weren't even planted when he went to prison and said he'd like to tour the country on his motorcycle."You spend 35 years in prison, and just the little things, like a grapefruit tree or an orange tree ... Those had vanished for me," he said. "I never thought I'd get a chance to see another one of these."

Bain is only one part of a much larger story. Although the registry report makes clear that most convictions in the U.S. are correct, the database shows a larger need to look closely at how the criminal justice system works, the authors say.

The report also shows which states have exonerated the most people. It notes that Illinois and New York may top the list in part because of the large presence of two major wrongful conviction centers in each state. From 1989 to 2011, the following states had tallied the most exonerations:

1. Illinois: 101

2. New York: 88

3. Texas: 84

4. California: 79

(Federal: 39)

5. Michigan: 35

6. Louisiana: 34

7. Florida: 32

8. Ohio: 28

9. Massachusetts: 27

10. Pennsylvania: 27The report also takes a look at the leading cause of wrongful convictions for specific crimes.

The project's findings alone, the authors say, are reason enough to look closely and continue to monitor convictions across the country."We cannot prevent all false convictions, but we must not compound these tragedies by stubbornness or arrogance or, worst of all, indifference," the report says. "The more we learn about false convictions the better able we will be to prevent them, or failing that, to identify and correct them after the fact."

Read more on wrongful convictions:

Man wrongfully imprisoned for decades happy to start relearning life