Vietnamerica:

Interview with author and illustrator

GB Tran

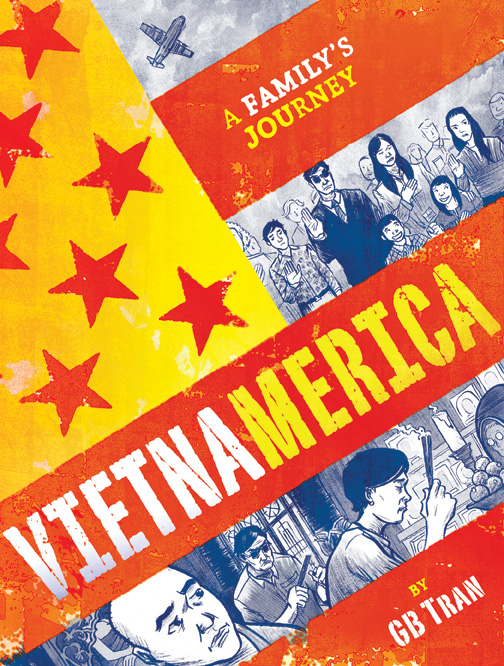

– APRIL 19, 2011POSTED IN: ARTS AND CULTURE, DESTINATIONSI don’t usually stop short at the sight of a book cover, but that’s exactly what happened at New York Comic Con this October.

A colorful illustration (below) caught my eye as I walked through a sea of comics and costumed Chewbaccas on the convention floor. In a twist on communist propaganda, the stars and stripes of the American flag were bathed in yellow and red.

This was my introduction to Vietnamerica, a graphic memoir by Brooklyn-based author GB Tran. The book follows his family’s journey from war-torn Vietnam to the United States, and is a great read for travelers and fans of graphic art.

Interview with the author

To create this compelling look at life during the Vietnam War, GB Tran traveled to Southeast Asia and interviewed family members who fought on both sides of the conflict.

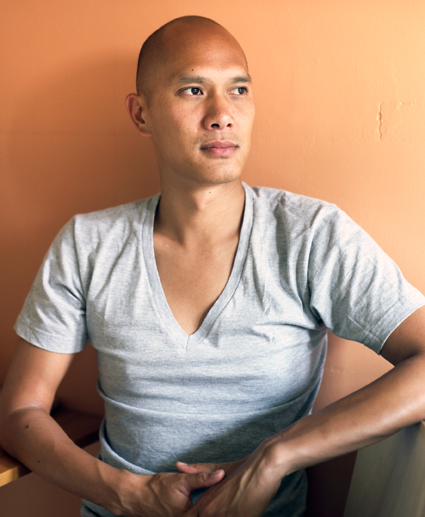

I sat down with the author on a brisk winter day at Café Orlin in the East Village. We discussed his travels to Vietnam, his inspiration for the book and how he scored a publishing deal.

Read on for GB Tran’s insights and advice for up-and-coming authors, and don’t forget to check outVietnamerica (available at local comic shops and on Amazon.com).

“Back” to Vietnam

Tran’s life is a classic American story. The youngest of four children, he was born in the United States a year after his parents left Vietnam. He spent his childhood in South Carolina, earned a BFA from the University of Arizona and moved to New York after college to start a career as an illustrator.

Given his background, I was surprised when he described going “back” to Vietnam in 2001. In fact, that was his first visit to the country.

“Doing this book, so many people have come up that have similar experiences. And we all say the same thing: the first time I went back,” Tran revealed at our meeting.

“And it’s just because [Vietnam] was so deeply rooted in our parents that it was always kind of considered our homeland. We had to go back sooner or later even though we had never physically been there before. I never realized I was saying that until someone else pointed it out to me and said, Oh, I say the same thing.”

Tran’s memoir clearly resonates with New Yorkers. At the book release party at SoHo’s Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art this January, every seat was filled and the crowd spilled into the hallway.

Not quite a tourist

Tran researched Vietnamerica during trips to Vietnam in 2001 and 2007. He traveled to both the north and south, visiting family and asking about their experiences during the war.

“I’m very fortunate that I still have a lot of family in Vietnam that cover a lot of geographical areas as well as social caste levels,” he explained over tea at Cafe Orlin. “Everything from my grandfather’s family, who basically are war heroes and are set up in the most posh, fancy, coveted part of Saigon, to the family that still farms in the Mekong Delta, in the rice paddies.”

Although he was asking about sensitive subjects, Tran was embraced by his relatives. “Even though these are people I never met before in my life, they really welcomed me,” he noted.

Vietnam is a popular backpacker destination, but Tran was not a typical tourist. Ever the artist, he spent several hours sitting on curbs, drawing street life. He met quite a few locals this way.

“I always had a sketchbook. Especially the second trip back in 2007, when I knew I was going to do this book,” he recalled.

“It’s just a way to feel another connection to the place you’re in. What you get when you’re sitting in a café and drawing the corner there for two hours, you notice all these small details that you normally wouldn’t notice because you’re busy going from one scenic stop to another. But when you sit there, and you’re really looking at the architecture, at the people across the street, at what they’re eating and doing—for me it’s a way to feel more rooted in where I’m at.”

Language barrier

As a Vietnamese-American in Vietnam, Tran found himself in an interesting situation. Locals often assumed he spoke their language, and talked to him in rapid-fire Vietnamese.

“I’ve traveled to places where I can’t speak the language, like Indonesia, and it’s a different experience. When you don’t understand the language, there’s no pressure to communicate, you can just enjoy being a tourist. One of the challenging things about knowing the language in Vietnam was that people constantly were talking to me,” he noted.

This complicated his trip; he wasn’t just a tourist, but was deeply connected to the people. After being immersed in the culture for several days, he began picking up the Vietnamese language.

“I started recognizing vocabulary in people’s conversations [and] I realized, how could I have ever learned what this word was growing up? I can’t imagine any context of my parents saying this, much less teaching me this word. But for some reason I would recognize the word.”

A bout of food poisoning turned out to be a breakthrough moment for Tran’s language skills.

“I got violently ill. Our tender American stomachs aren’t really fortified for that type of cuisine. So the best thing about getting violently ill for a few days—the whole vomiting, explosive diarrhea, fever, all that crazy stuff, was near the end of it, I started thinking in Vietnamese… When that happened, I was really excited, actually. Then unfortunately I left and it all disappeared overnight.”

His big break

GB Tran was discovered at San Diego’s Comic Con, when a Random House editor stopped by Tran’s booth and took an interest in his self-published comic books. After securing a book deal and advance for Vietnamerica, Tran was able to take two years off from his day job as a commercial illustrator to focus on the memoir. He calls this the best two years of his life.

“I woke up every morning and I got to draw. I’m sure my wife got sick of me just being in the apartment all day, but it was definitely the best two years of my life. Not only drawing all day but drawing about something that I was really passionate about,” he recalled.

During this time, Tran made several trips to Arizona to interview his parents about their experiences in the Vietnam War. They were skeptical about the project at first, but opened up after seeing Tran’s commitment.

The author turned to books, movies and Google images to ensure he got the period details right in his illustrations.

Any freelance writer knows it can be challenging to focus on assignments with distant deadlines. However, Tran maintained a daily routine that ensured he didn’t fall behind.

“I sketched the entire book first, before moving on to penciling, drawing, inking, coloring. So I knew every day, every week, what I was going to be doing for the next weeks or months. The longest stretch of doing the same thing day in, day out was inking, which took seven months… I would just wake up and ink for twelve hours.”

Tran wrote and illustrated Vietnamerica, and sees the two disciplines as being intertwined. “I think that’s the hallmark of a cartoonist, as opposed to a writer or illustrator,” he noted. “We can’t just write a story and we can’t just draw a story, we have to do it back and forth.”

Advice for aspiring authors

For Tran, writing a memoir about his family history was intense; he was essentially reliving experiences from a very emotional period in his parents’ lives. “I didn’t want to live in this space for an extended amount of time,” he revealed in our interview.

One of the key challenges of writing a book is knowing when you are finished. “You’ve got to be OK with letting go. This book has typos in it,” noted the author, who spotted a few misspellings after the book went to print. “I had to walk away at some point or another. I did the best that I could, given the resources and time I had.”

Tran is modest about his success; he concedes that he worked hard at comic conventions and events to get his name out and sell his work, but considers the book deal a lucky break.

When asked to give advice to aspiring authors and illustrators, Tran stressed the importance of following through on ideas. He advises other cartoonists,

“Just to finish a story. People who want to do comics, they have a billion ideas and they start a billion ideas, but until they actually finish one of them, it’s still kind of a pipe dream. I’m guilty of this too– just having a bunch of projects and starting them and after 10 pages, be like, nah, I’m bored. All the great cartoonists that I love, it’s not because they have great ideas—everybody has great ideas—it’s because they have the discipline to execute their ideas.”

What’s next

Tran continues to show his work at comic conventions throughout the US. “If someone’s willing to spend their hard-earned money on my book, I’d like to thank them in person, or meet them, or shake their hand,” he said.

He’s also planning a second project that will take him back to Vietnam.

“This book is basically 20 percent of all the stories I heard [from family members]. The best advice I got was to tell the shortest story possible, so that meant constantly editing. If the event didn’t help propel this story, then I just had to leave it out… there’s a lot of stuff on the floor that I would like to go back and dig a little further on.”

For more info

Visit www.gbtran.com and follow @vietnamerica on Twitter for more information on GB Tran’s work and for a list of his upcoming appearances.

Pick up a copy of Vietnamerica on Amazon.com or at your local comic shop.

VIETNAMERICA from Joe Tomcho on Vimeo.

__________________________

Thursday, June 23, 2011

Graphic Novel Review:

Vietnamerica

Bennett here, taking a break from not treating John Matrix's kidnapped daughter very well.The great American novel. On the surface, it’s a simple concept, but a loaded one. Say you want to write the great American novel in any kind of company and watch the snickers and condescension rain down. In a country with such a variety of faces, with so many strikingly different groups of people, and with such disparity among classes, is there such a thing as the “Great American Novel?” Can there be? Or can you simply appeal to one group at a time?

It’s the same type of discourse that permeates the Asian American community—is there such a community, and if so, is it a legitimate one? A pan-Asian American community implies a shared history, a shared story, but clearly that hasn’t been the case. Not when you consider vastly different issues such as the Japanese internment versus the Southeast Asian exodus. The only real, legitimate reason for a pan-Asian American community seems to be to react to outside groups (mainstream America) who would confuse East Asian ethnicities, as happened in 1982 to Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American man who was bludgeoned to death by two out-of-work auto workers in Detroit after being confused as Japanese. The two auto workers were given probation. Today, incidentally, is the twenty-nine year anniversary of his death.As Vietnamese American, I consider myself a detractor of the pan-Asian American identity. While experiences such as Vincent Chin’s death indicate a need for a banner under which Asian Americans can assemble, Asian America should be a more organic concept, one that compartmentalizes itself more often than not. I have no interest in discussing Filipino migrant workers of the 1800s any more than I do Bolivian immigration in Northern Virginia. Black America has, for the most part, a shared history that is integral to the American consciousness and identity. Asian American history operates as piecemeal, a mosaic of groups which have yet to blend together to form a coherent identity informed primarily by a universal American experience. Do Chinese Americans on the west coast who have been here for lord-knows-how-many generations have anything to do with the Hmong that arrived in the 70s and 80s? Why should we think they do? Simply because, to mainstream Americans, all East Asians look similar ?

The great Vietnamese American novel is an enticing idea, one that has been tossed around and attempted to varying degrees of success. One of my favorite memoirs, Catfish and Mandala: A Two-Wheeled Voyage Through the Landscape and Memory of Vietnam, by Andrew X. Pham, retells the grand, epic journey of a Vietnamese American man bicycling through Vietnam, searching for an understanding of his heritage, and, at some level, to search for what his family has lost to the cloud hanging over them, the sense of impending doom—a feeling that manifested as dysfunction because they would not, and could not address it. Recently, Gia Bao (GB) Tran’s (graphic) novel, Vietnamerica, attempted to tell the great Vietnamese American story. Though I hesitate to put “graphic” in there at all, as the medium is too easily derided as low-art, or unintelligent. None of these adjectives describe Vietnamerica. Tran, who was born in the USA in 1978, never had much of a strong relationship with his Vietnamese heritage. The book recounts his parent’s often muddied history and their flight from Vietnam, and, briefly, their assimilation into American society.

It’s a common immigrant story, right? Departure, loss, assimilation, and the subsequent fracture in families, and ultimately the reconciliation of heritage, family, identity. And it’s so very tempting to write from the Vietnamese American point of view, particularly as a member of the 1.5 Generation. There are countless American stories about Vietnam, a revolutionary and devastating place and time for not just the country, but the world. Revolutions spread through countries colonized by western forces, and it all seemed to stem from a little country in Southeast Asia. And America cares about Vietnam, if only to see how its own identity as the Western superpower has been influenced by her. Interestingly, Tran spent much of his life as someone who didn’t care for Vietnam, didn't care for the pain and history his parents (and their parents) endured as they wound their individual ways through French occupation, and civil war, and didn't care about how his heritage and history has changed the course of the country he now lives in.

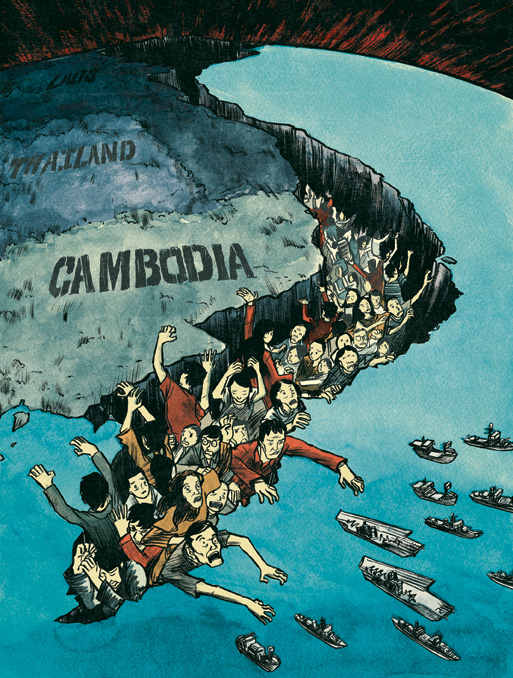

Vietnamerica’s a beautiful graphic novel, absolutely magnificent in scope, ambition and writing. There are so many moments of poignant reflection: Tran's family doing what they had to in order to stay together; dealing with overbearing parents; the heartache and honesty of a home headed by a man who can’t adapt to American parenting. The art is somewhere between Joe Sacco’s Palestine and the graphic novel that Vietnamerica inevitably draws comparisons to: Art Spiegelman’s Maus. The gritty look of the art suits the book perfectly. The story is dirty, gritty, honest, and done in muted colors, almost a muddied look in black-and-white, well-chosen for a time that ironically can never be considered in black-and-white terms. Tran has created a complex, never-easy-to-read history that evokes an astonishing sense of loss and alienation. I won’t call it a triumph, but it’s certainly a resounding success, a wonderful addition to the Vietnamese American lexicon.

The two major problems with Vietnamerica become apparent about halfway in: the structure is so jumbled that instead of evoking a sense of confusion and muddled history that Tran may have been aiming for, it, at times, simply becomes difficult to read. Characters weave in and out of the story, unnamed, or named, or unrecognizable because of the artwork. We switch tracks constantly, jumping from Tran’s mother’s tale to his father’s, without much of a transition alert for the reader. We begin to forget things that came before, and things that should have much more weight are lost altogether. And the book lacks symmetry, a way to draw it all together. It starts well with Tran’s father visiting his estranged, dead father’s estate and leaving in a hurry, hinting at a tension, a driving point that would propel the story. But then we move outward, encompassing Tran’s mother’s story, and so much more of Tran’s father’s history, that the estranged father angle gets lost and by the time we revisit it, we’re left wondering what we’re supposed to take away from this at all.

In this respect, the main problem becomes obvious: there isn’t enough authorial content. That is, we need more direction provided by GB Tran himself. I get that this is a memoir, and one that he uses to tell his family’s (and ultimately Vietnam’s) story, but we need more of Tran. We need him to point us to the story, to the conflict that drives us. Because while the downfall of South Vietnam and the subsequent, staggered flight from there is a huge conflict, it’s strangely not enough to drive this narrative, because we’re not invested in Vietnam as a country, we're invested in the character that should be driving us: GB Tran. This should be about him, about how he has related to this incredible history with such complacency, and how he became driven to find out more about everything. That narrative layer is sorely needed to draw everything together, and the book really picks up when we get the small flashes of Tran’s more recent, personal history.

No review would be complete without a brief mention of Maus. And, really, that book works because Spiegelman used himself as the main driving force. We followed Spiegelman as the protagonist, as the one who filters the Holocaust story from his father, and we get the relationships and the give-and-take of a family dynamic. Tran completely bypassed this important part of the experience. And it’s not like he isn’t aware of Maus—there are points that are clearly influenced by Maus, the artwork in particular. The large, page-sized panels such as the one in which countless Vietnamese are shown clawing their way out of a ditch shaped to replace Vietnam on a map of Southeast Asia could have been taken directly from the pages of Maus.

While Vietnamerica stops just short of creating an immersive tale, it does give enough to push the reader through, and for the most part, it’s an exhilarating experience. Sure, there are confusing passages, and vague, ambiguously drawn characters, but the drama of the family struggling to stay together trumps most of these issues. Perhaps a sequel would not be out of the question? The title, after all, implies a larger story, and his family, from the upper-academic echelons of Vietnamese society, tells only a small portion of the Vietnamese American experience. Additionally, Vietnamerica operates too much as exposition and within Vietnam to really earn the title. And I really want to explore this story more, especially if it dealt with issues unique to the children of refugees. But a sequel doesn’t even have to be about Tran and his family, necessarily… After all, he came with the First Wave of Vietnamese refugees—and the most common image of the Vietnamese refugee is from the Second Wave, the Boat People. But that’s completely beside the point. Vietnamerica is a worthy read, and a worthy addition to any library.

Vietnamerica the Beautiful:

An Interview with G.B. Tran

G.B. Tran's parents fled their native Vietnam before he was born and raised him here in America. All his life, Tran's parents tried to build a connection between Tran and his heritage, but it was one he resisted. It wasn't until fairly recently that he made a trip to his parents' homeland, and that trip inspired the heartwrenching and poignant memoir Vietnamerica. We talked to Tran about the powerful experience of creating this book.

In the afterword to Vietnamerica, you say that making this book broke your heart. How so?

There was so much about my family's past that I had no clue about, and uncovering and telling their stories took me from joy to sadness and everywhere in between over and over again. This constant emotional rollercoaster ride, spread over several years, was very exhausting.

Do you wish now that you had gone to Vietnam earlier in your life? How do you think it would have affected you if you had?

I think things happen when they need to happen, so I don't regret not going to Vietnam earlier. Considering the different mindset I had in my younger years, what's to say that an earlier trip would have even resulted in this book? Whether it was because I was less interested then, didn't have enough confidence to tackle on such an immense project, etc.

How did making this book change your relationship with your parents and the rest of your family?

For my parents, I hope it's made us more empathetic to each other. For the rest of the family, it's secured my role as the deadbeat artist. Every family should have one those.

Can you now imagine doing what your parents did—leaving the country of their birth at that age and beginning anew in a strange new foreign land?

That was a constant question running through my mind while working onVietnamerica, and the main reason for the emotional rollercoaster previously mentioned. Considering my dad's painting career was just taking off when he had to flee, it was impossible not to imagine myself in his shoes.

Obviously the Vietnam War represents one of the most fractious eras in American history. For you personally, it resonates in a similar way with your family dynamic. Growing up, what understanding did you have of the political situation of Vietnam and what your parents had to escape from?

My parents didn't raise me on stories of their past. That, combined with my own lack of interest, meant I had no understanding of Vietnam's political turmoil. This would later become one of the driving forces behind creating Vietnamerica—that desire to better understand what my parents were trying to escape from.

Yes, in the sense that as I researched and gathered family memories, I had to piece the stories together like a puzzle. Early on, I organized them chronologically to determine which event would be the book's climax. Once that was figured out, I kinda reverse-engineered the narrative, which led to splitting it into two main timelines that naturally converged at the end for the climax. In a way, I also think it was my subconscious wanting to simulate how disorienting it was for me to unravel my family's history in the first place.

What parts of your parents’ stories did you never know or properly understand before beginning this project?

With the exception of the scenes involving me at some point in my life, I was totally clueless on about 99 percent of it.

What reaction to the book have you had from family members?

Pride to curiosity, I think. The former with my parents, and the latter with the extended family. Thankfully, the most critical comment has only been my mom complaining I didn't draw her beautiful enough.

What are you working on next?

I'm spearheading a book with a group of amazing cartoonists, illustrators, and animators that continues to explore one of the major themes of Vietnamerica in what I hope is a very unique and poignant format. Mum's the word till we find a publisher.

As for the next project that I'm writing and drawing myself, I'm taking some of the unused Vietnamerica research and telling a smaller story hopefully to be serialized online. There's just so much material left on the cutting room floor that I wanted to further explore, but just not through the same emotional lens asVietnamerica. I feel the former is 90 percent seriousness and 10 percent humor, so this next project is 10 percent seriousness and 90 percent humor. And it has a robot in it.

-- John Hogan