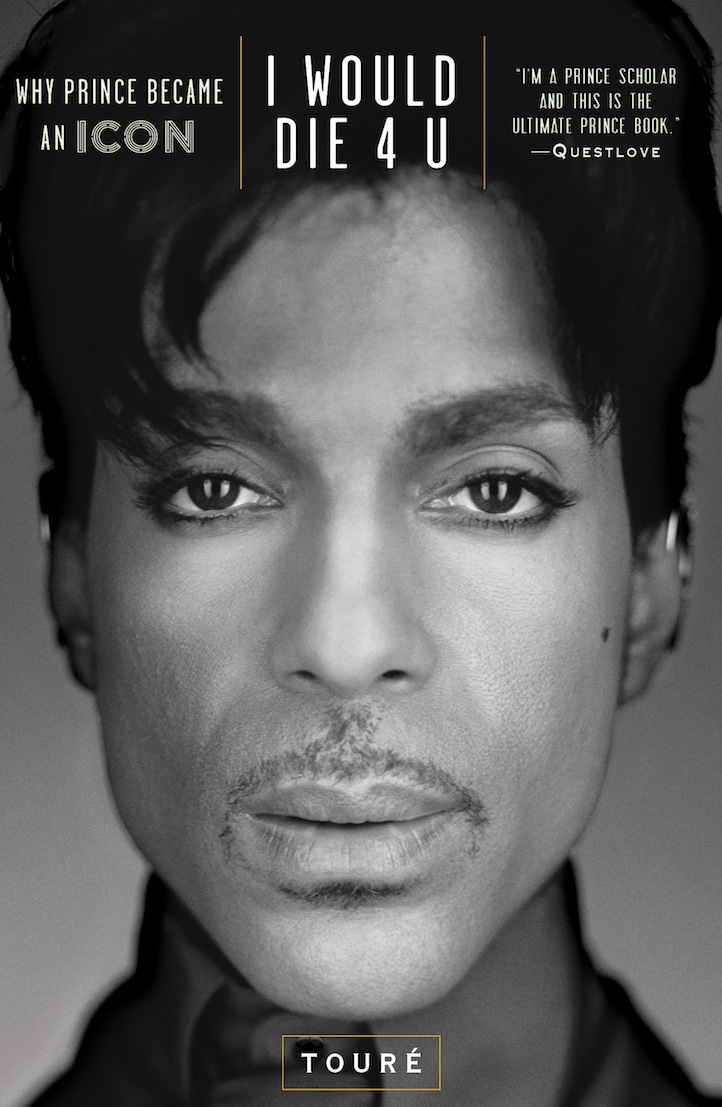

Touré Talks About

His New Prince Book,

“I Would Die 4 U”

03.19.2013

Author

Quinn Peterson

Prince is one of the music’s most talented and revered artists, and at the same time, also one of its greatest mysteries. In his new book, I Would Die 4 U: How Prince Became An Icon, popular author, journalist, TV personality and culture critic Touré digs into what allowed Prince to emerge as a revolutionary pop artist transcending race and all other boundaries to become the voice of a generation. Based on three lectures he gave at Harvard a year ago, Touré discusses how and why Prince is an icon for Generation X in particular, a product of his times – namely MTV’s launch, growing sexual awareness and porn chic in the mainstream and improved racial equality – and the constant allusions to religion in his music.

Ultimately he argues that, “by virtue of his reach, his seductive appeal, and his artful archness, Prince is not only a master many times over of pop, soul, and rock music, but also one of history’s most significant religious artists.” I Would Die 4 U contains Touré’s personal anecdotes from his own experience interviewing Prince years ago, as well as interviews with Paisley Park Records president Alan Leeds, Revolution Guitarist Dex Dickerson, Purple Rain sound engineer Susan Rogers, Questlove and others.

Life+Times got a chance to talk with Touré about his latest book and The Artist Formerly Known As Prince.

Life+Times: Talk about going from your lectures at Harvard to making this a full-blown book, and why you decided to do that.

Touré: Well, I wrote the lectures with an eye toward making it become a book. That was always my plan. I didn’t want to spend a year digging into a really interesting subject then not go all the way and make it a book. Skip Gates invited me to these lectures and I wanted to do something that I thought was really interesting and that I’d be happy spending a year focusing on. After I did the lectures, as a writer, it just took a little shaping in terms of a couple of things that would change from a spoken document to a written document. The lectures were one lecture per day over three days, so you end the lecture saying things to try to make sure people will come back tomorrow. In terms of writing, you don’t to do that, so I sort cleaned up the end of chapters like that. And, given a little more time, I had the opportunity to get more people on the phone, find more people and interview more folks. So I was able to broaden my discussion by finding new people.L+T: The book brings everything together by saying Prince’s talk about sex is a way to lure people into a greater message. Did you know that going in, or did you find that out as you researched?

Touré: That was definitely a sort of revelation that came about as I was researching. It’s something that I figured out out as I was reading through, looking at the amount of religion and sexuality in his work. There’s a number of things that I discovered about him as I was researching. I knew a lot but I learned a lot, and it’s always exciting as a writer when you can learn as you’re researching a subject.L+T: What were some other new revelations that you had?

Touré: I had not really understood “Purple Rain.” Like everybody, I looked at it as this great song, [but] I really didn’t have any idea what he was talking about. Talking to Questlove, Bible scholars and some other people, they started pointing to baptism and water as a baptism symbol. It’s sort of oblique, but if you read really hard, there’s a present story of a person who wants redemption because this relationship is breaking up, but they still love that person. They did everything right in the relationship but the relationship has to end. You want to be sort of blessed in that moment, redeemed in that moment, like, “Hey, you’re not a bad person, it’s ashamed it had to end, but it had to.” Then that third verse is so crucial, where Prince is kind of saying, “follow me, I am a messiah figure.” It’s extremely powerful and important in trying to understand who he is.L+T: One of the most fascinating parts is when you talk about him “passing” as biracial. Can you expand on that?

Touré: Sure. His mother is Black. I don’t have a photograph of her, but several people who met her or spoke to her told me she was Black. Think about it ethnographically: Mattie Shaw, from Louisiana, grew up in the projects, known for playing basketball very well, moves to Minneapolis, becomes a jazz singer in her early 20s, and falls in love with a marries a much older Black band leader who already had a family. It sounds like a sister to me. If that was the only thing I had, that would be circumstantial. There were no miscegenation laws in Minneapolis that I could find at that time but it was not usual. Minneapolis is one of the places I’m told that was ahead of the curve on those issues for a long time, but still, if we apply occam’s razor, it appears most likely that his mother was Black. And there’s no conversation that his father was not Black. Obviously, [he's] very light and mixed at some level, but generally, when we’re talking about mixed or biracial, we’re talking about one parent is a different race, and that is, from all the evidence we have, not the case. But, Prince very much wanted to have the largest possible audience that he could have. So, he tells a few of the first reporters who interview him that his mother is white, Italian. The way journalism goes, [if] the first three people interview somebody, report a certain fact, you may not keep asking; so if you’re the sixth, seventh, eighth person to interview him and several articles have said this is a fact – “he’s mixed, his mother’s white” – you wouldn’t keep asking that question. That’s just how we are. You might ask about being mixed, and now you’re helping him live the fantasy. Putting a white woman as his mother in Purple Rain helped push that further. What he was trying to do was not run away from being Black, he very much loved being Black and his music is unquestionably Black; but he wanted access to the larger mass culture and he also wanted to not be tied by the expectations of what being a Black recording artist would be. He wanted to break out of those boundaries. To want that in the late ’70s-early ’80s was very revolutionary, unusual and unexpected. For him to be able to break out, he had to be demanding of the right to do rock-and-roll as well as funk and soul. Part of the sell within that was saying, “I’m mixed,” or, “Don’t put me in the box.” [He would] not do certain tours that would have him on the undercard for certain artists who would pigeonhole him. He would do tours where he would do a sort of white venue, then do a traditionally Black venue, so he’s hitting both sides. Record businesses would have a sort of segregation where there would be a Black music department which would market you to Black media, try to get you on the urban charts, etc., that would typically have smaller staffs and smaller budgets as opposed to the pop [departments], which would be larger budgets, larger staffs, larger potential to become a superstar which was always his goal. He’s passing for mixed as an attempt to gain some white-skin privilege or mixed-skin privilege – but that’s not a thing, you wouldn’t benefit from being mixed, you’d benefit from being partially white. But in no way is he rejecting or running from Blackness. I think some of us are rightly suspicious, nervous, anxious, upset about people who pass, but I think a lot of the time, they are not hateful or rejecting Blackness. They see a loophole in the social construct of race and they say, well, “If I rewrite myself (which is a typical American thing), then I can have access to white-skin privilege and see how far I can go in this world. There’s no boundaries in this world as opposed to dealing with the boundaries that have been imposed on us living with white supremacy and the expectations of us.”L+T: Was there any backlash from Black audiences or Black radio for that?

Touré: Not that I know of. I think there were definitely some Black people who might have been like, “It’s a little too rock-and-roll for my taste,” especially in the era of “Purple Rain,” which is a tad bit silly in that we created rock-and-roll. If you look at Controversy and 1999, they’re very soulful, funky albums, Around The World In A Day had some ’60s-inflected soul, then you get back to LoveSexy, Sign O’ The Times, there sort of albums, it’s very, very souful. Some funk, but lots of soul. But that piece, I don’t think we realized it, because a lot of people thought he was mixed. I think it took a while for people to realize, “Oh, he was teasing us.” But what he was really doing was trying to escape the boundaries of demographics, of the sayings, “you’re Black, ergo X, Y, Z, or you’re female, ergo X, Y, Z.” He wanted to be free and you see that in [his questions] like, “Am I straight or gay? Male or female? Black or white?” He’s really messed with you. That’s sort of an ’80s thing, “I’m not going to let the demographics determine who I am and how I’m perceived.”L+T: How important was it for him to be from Minnesota and how did that shape his outlook?

Touré: It definitely shaped him in several ways. It’s a place where there was a lot of connection between Black and white cultures. A lot of mixed relationships, so that was very natural in his experience. He was not part of a big city, so in a way he’s able to be part of this music culture, but in a way, he’s able to fly under the radar as opposed to growing up in L.A., New York, what have you. He was also exposed to a lot a great radio stations, but they’re pop radio stations. They didn’t have all the stations that we have in New York or L.A., so a lot of people talked about the impact that the pop stations had on him and how the records that he heard – these pop records – influenced who he became.L+T: A couple of times in the book you reference Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and the importance of timing. If Prince hits five years earlier or five years later, are we having this conversation?

Touré: I think so. It’s impossible to know, but I think so because the talent would still be there. But what I’m talking about is definitely affected and influenced by [him] growing up at a time when gospel is becoming secular music and is played seven days a week, and he’s able to interact with Rick James, George Clinton, Al Green and those sort of people. Then, when he emerges, he’s able to interact with the highly sexualized culture of the ’80s and be a natural progression from James, Clinton, James Brown, etc. It’s impossible to know. I think yes, we’d still be talking about him because the level of talent was such that he would still be famous, but would he be the same level of icon, well that’s un-knowable.I Would Die 4 U: How Prince Became An Icon by Touré is available March 19th on Amazon.

__________________________

Now Read This:

Touré Hits The Courts

With Prince

Touré plays basketball with The Purple One. Read an excerpt from his new book 'I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became An Icon.'

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

Dave Chappelle as Prince on the basketball court (video still)

Dave Chappelle as Prince on the basketball court (video still)

The writer and tv host Touré has a new book out, called I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became An Icon. It's a study of the cultural impact of the artist behind such iconic albums as Purple Rain and Diamonds And Pearls. In one of the most memorable passages, Touré is invited out to Paisley Park to shoot hoops. This is a familiar setting to fans of the comedian Dave Chappelle -- a popular skit from his Comedy Central show dramatizes what this might be like. Well, here's the real thing:

From I Would Die 4 U, by Touré:

I got a glimpse of Prince’s weird ways of interacting with people when I spent time with him at Paisley Park for a cover story I was writing for the now-defunct Icon magazine. It was 1998, and we did an interview that was too short and incomprehensible to support a cover story, partly because he didn’t allow recording devices, which made it nearly impossible to capture the dramatic, diversion-filled paragraphs he speaks in and that sometimes went in circles, using parables and sentences so cryptic that they’d fit in a David Lynch film. When I looked back at the notes I’d scribbled while he talked I kept asking myself, what did that mean? The notes I wrote did little justice to what he had said and I couldn’t commit his quotes to memory due to his unique language. So, his quotes, in my story, were often approximations of what he said, usually more his intent than his exact words. Apparently, he intends to be cryptic. An former girlfriend said, “Sometimes he says things that make you feel like you haven’t gotten an answer. He leaves you to have to think about every word he says, which is kind of irritating.”

After our interview, I asked his publicist if I could email him more questions. Because I had a cover story to do, it was allowed. I emailed Prince ten. The last question was, “Will you play basketball with me?” (I knew that in high school the only thing he really cared about, apart from music, was basketball. He played on his high school team and by all reports he was good although his chance to get a lot of playing time was stymied by being small.) Well, one night a few days later, he emailed back answers to some of my questions and ignored others, but to my question about basketball he wrote, “Any time brother . . . :).” Any time? I put a basketball in my bag and boarded the next possible plane to Minneapolis. I don’t think he expected that. I wanted a real human interaction with him but didn’t know if he could or would give it to me.

Paisley Park is a large, modern-looking building located in a field just outside of Minneapolis, in tiny Chanhassen. From the outside, the large white-tiled walls make it look like a Mercedes dealership without windows. Inside Paisley, which houses recording studios, a large rehearsal stage, and offices, there was a quiet manicness, as if it’s a music lover’s Alice in Wonderland. Oversized comfy chairs of all colors sit amid pillars topped with gold disks and thick blue carpeting dotted with zodiac signs. A flock of golden doves seemed to tumble from the sky in a painting on one of the walls. (People said the building had been a clean, minimalist white for fifteen years, but had become colorful, either because of the influence of his new wife Mayte or in anticipation of a baby.)

As Prince sat for a photo shoot that would accompany my story, he spoke to us in weird but witty asides. Flipping through Vanity Fair, he came to an article about Ronald Reagan, long after his presidency, battling Alzheimer’s.

Prince asked, “Think Reagan has Alzheimer’s?”

“Yeah,” I said.

He gave me a sly look as if to say, don’t believe it. I’d heard he was a conspiracy theorist. I laughed and began writing what he’d said in my notepad.

“Don’t write that!” he said playfully. “I’ll have the Secret Service at my door.” He adopts a mock federal agent voice. “You say somethin’ about Reagan?”

The room cracked up. I asked, “Why would they lie about that?”

He said, “To keep him from answering questions.”

When I pulled my basketball from my bag and told him I wanted to play ball he told an assistant to “clear out the back to play basketball” and get his sneakers. I’d heard he played in heels. “Who told you that?” he said in an incredulous tone, as if that were the most ridiculous suggestion ever. I said, “I don’t remember.” He said, “A jealous man told you that story.” (Not quite: Wendy Melvoin once told the Minneapolis Star Tribune that Prince would sometimes break from rehearsals to play basketball . . . in heels. She said, “He would go outside and play basketball in the high heels, which he’s now paying for, I’m sure. With his heels on, he could run faster than me, and I was wearing tennies.”)23

Prince disappeared and, after a short while, the two-person photo team and I were led toward the back, into the rehearsal room. When we got there, Prince was jamming with his band while wearing a tight, almost sheer, long-sleeved black top and tight black pants. He had changed since the photo shoot only minutes before. After a few songs, he put down his guitar and walked around a corner to where there was a single basketball hoop and enough room to play half court. He slipped off his cream colored heels and reached into a box of sneakers and pulled out some old and clearly used, but not too tattered, redand-white Nike Air Force high-tops. He laced them up and with that, the guy who was a backup point guard for Central High in Minneapolis was ready to ball.

He picked up my ball and made a face that was understood in international shit-talking parlance to mean I’ma kick yo’ ass, and started knifing around the court, moving quick, dribbling fast, sliding under my arm to snatch rebounds I thought for sure I had. He was showing off, being competitive, and, yes, engaging me in the same way I’d interacted with so many men I had played basketball with before. He moved like a player and played like one of those darting little guys you have to keep your eye on every second. Blink and he’s somewhere you wouldn’t expect. Lose control of your dribble for a heartbeat and he’s relieved you of the ball. He jitterbugged around the court like a sleek little lightning bug, so fast he’d leave a defender stranded and looking stupid if he weren’t careful. With his energy and discipline it was a rapid game, but never manic, or out of control. Still, we were both rusty so most shots missed, clunking off the side of the rim or the backboard. After a while, there was not much of a score. I scored on a drive that felt too easy and as the ball dropped in I looked back at him. He said, “I don’t foul guests.” Okay. On the next play I drove again and the joker bumped my arm really tough, fouling me. Funny dude.

After a time he and I teamed up against my photographer (who Prince had told not to take pictures of the game) and Morris Hayes, his six-foot-four blond, Afroed keyboardist. Prince played like a natural leader, setting picks and making smart passes, showing a discipline many street players never grasp. Then, he took it boldly to the hole, twisting through the air in between both opponents to make a layup. It was, maybe, a bit too aggressive, but he exhibited the confidence of a man who’s taken on the world and won.

Once, I was dribbling the ball at the top of the key when I saw he was in good position under the basket. I flicked a quick, no-look pass his way. The ball zipped past both defenders but then I realized he didn’t know it was coming. I started to yell out to him, the man I had known, sort of, for over fifteen years. I called out, “Prince!” But this was during the Symbol period, when his name was unpronounceable and you weren’t supposed to call him Prince. Titanic faux pas! Would he storm out and banish me from Paisley Park? I had this thought process as the word “Prince” was coming out of my mouth so really what I said was, “Pri . . . !” like the first syllable, then caught myself and slapped my hands over my dirty mouth as if to keep that sound and any other from getting out. The ball sailed past him and out of bounds. He jogged off to retrieve it and as he walked back he had a badass smirk on his face. I looked at him, like, “What?” I had no idea what would happen next. Then the man laughed as he said, “He didn’t know what to call me.” He loved the confusion, loved that I didn’t know how to connect with him, that I was off balance and couldn’t even call him by a name much less really know him. That symbolized so much. After balling and bonding and being guys together, teammates, he still relished there being a barrier between him and me, keeping us from getting close. Still, I kept trying.

A few moments later I passed to him on the baseline and, full of poise, he coolly threw up a jumper. It swished in and we won the game. He was too cool for school about it. We high-fived, but he still kept a distance. After that, we took a walk alone together through a giant closet, a warehouse-sized room filled with clothes on racks. He pointed out some past tour outfits and abruptly gave me a black-andgold hockey jersey with his logo on the front. Then, he showed me an old picture of him playing tennis and said he was really good at the sport. He said, “I was too small to play”—he pointed back toward the basketball court—“in high school. I like tennis better than that.” Finally, he was sharing with me, taking me beyond image making and toward the real man. I thought we were about to really connect for a second. I said something about playing tennis—I had a vision of somehow playing with him. Then, he abruptly excused himself in a way that made it clear that this was not goodbye. Then he was gone. An hour later I was still in the lobby of Paisley Park, waiting to keep talking or say goodbye or something. Someone came down and said it was time to go. They said that saying goodbye wasn’t his way. Perhaps it would come too close to a normal human interaction.

>via: http://soundcheck.wnyc.org/blogs/soundcheck-blog/2013/mar/19/toure-i-would-di...