Gentrification

and its Discontents:

Notes from New Orleans

by Richard Campanella 03/01/2013

Readers of this forum have probably heard rumors of gentrification in post-Katrina New Orleans. Residential shifts playing out in the Crescent City share many commonalities with those elsewhere, but also bear some distinctions and paradoxes. I offer these observations from the so-called Williamsburg of the South, a neighborhood called Bywater.

Gentrification arrived rather early to New Orleans, a generation before the term was coined. Writers and artists settled in the French Quarter in the 1920s and 1930s, drawn by the appeal of its expatriated Mediterranean atmosphere, not to mention its cheap rent, good food, and abundant alcohol despite Prohibition. Initial restorations of historic structures ensued, although it was not until after World War II that wealthier, educated newcomers began steadily supplanting working-class Sicilian and black Creole natives.

By the 1970s, the French Quarter was largely gentrified, and the process continued downriver into the adjacent Faubourg Marigny (a historical moniker revived by Francophile preservationists and savvy real estate agents) and upriver into the Lower Garden District (also a new toponym: gentrification has a vocabulary as well as a geography). It progressed through the 1980s-2000s but only modestly, slowed by the city’s abundant social problems and limited economic opportunity. New Orleans in this era ranked as the Sun Belt’s premier shrinking city, losing 170,000 residents between 1960 and 2005. The relatively few newcomers tended to be gentrifiers, and gentrifiers today are overwhelmingly transplants. I, for example, am both, and I use the terms interchangeably in this piece.

One Storm, Two Waves

Everything changed after August-September 2005, when the Hurricane Katrina deluge, amid all the tragedy, unexpectedly positioned New Orleans as a cause célèbre for a generation of idealistic millennials. A few thousand urbanists, environmentalists, and social workers—we called them “the brain gain;” they called themselves YURPS, or Young Urban Rebuilding Professionals—took leave from their graduate studies and nascent careers and headed South to be a part of something important.

Many landed positions in planning and recovery efforts, or in an alphabet soup of new nonprofits; some parlayed their experiences into Ph.D. dissertations, many of which are coming out now in book form. This cohort, which I estimate in the low- to mid-four digits, largely moved on around 2008-2009, as recovery moneys petered out. Then a second wave began arriving, enticed by the relatively robust regional economy compared to the rest of the nation. These newcomers were greater in number (I estimate 15,000-20,000 and continuing), more specially skilled, and serious about planting domestic and economic roots here. Some today are new-media entrepreneurs; others work with Teach for America or within the highly charter-ized public school system (infused recently with a billion federal dollars), or in the booming tax-incentivized Louisiana film industry and other cultural-economy niches.

Brushing shoulders with them are a fair number of newly arrived artists, musicians, and creative types who turned their backs on the Great Recession woes and resettled in what they perceived to be an undiscovered bohemia in the lower faubourgs of New Orleans—just as their predecessors did in the French Quarter 80 years prior. It is primarily these second-wave transplants who have accelerated gentrification patterns.

Spatial and Social Structure of New Orleans Gentrification

Gentrification in New Orleans is spatially regularized and predictable. Two underlying geographies must be in place before better-educated, more-moneyed transplants start to move into neighborhoods of working-class natives. First, the area must be historic. Most people who opt to move to New Orleans envision living in Creole quaintness or Classical splendor amidst nineteen-century cityscapes; they are not seeking mundane ranch houses or split-levels in subdivisions. That distinctive housing stock exists only in about half of New Orleans proper and one-quarter of the conurbation, mostly upon the higher terrain closer to the Mississippi River. The second factor is physical proximity to a neighborhood that has already gentrified, or that never economically declined in the first place, like the Garden District.

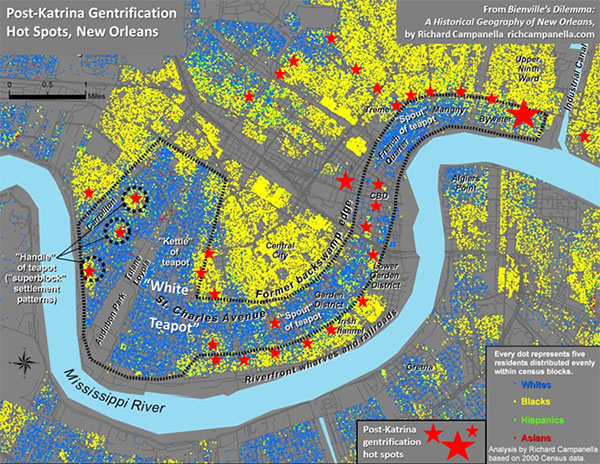

Gentrification hot-spots today may be found along the fringes of what I have (somewhat jokingly) dubbed the “white teapot,” a relatively wealthy and well-educated majority-white area shaped like a kettle (see Figure 1) in uptown New Orleans, around Audubon Park and Tulane and Loyola universities, with a curving spout along the St. Charles Avenue/Magazine Street corridor through the French Quarter and into the Faubourg Marigny and Bywater. Comparing 2000 to 2010 census data, the teapot has broadened and internally whitened, and the changes mostly involve gentrification. The process has also progressed into the Faubourg Tremé (not coincidentally the subject of the HBO drama Tremé) and up Esplanade Avenue into Mid-City, which ranks just behind Bywater as a favored spot for post-Katrina transplants. All these areas were originally urbanized on higher terrain before 1900, all have historic housing stock, and all are coterminous to some degree.

Figure 1. Hot spots (marked with red stars) of post-Katrina gentrification in New Orleans, shown with circa-2000 demographic data and a delineation of the “white teapot.” Bywater appears at right. Map and analysis by Richard Campanella.

The frontiers of gentrification are “pioneered” by certain social cohorts who settle sequentially, usually over a period of five to twenty years. The four-phase cycle often begins with—forgive my tongue-in-cheek use of vernacular stereotypes: (1) “gutter punks” (their term), young transients with troubled backgrounds who bitterly reject societal norms and settle, squatter-like, in the roughest neighborhoods bordering bohemian or tourist districts, where they busk or beg in tattered attire.

On their unshod heels come (2) hipsters, who, also fixated upon dissing the mainstream but better educated and obsessively self-aware, see these punk-infused neighborhoods as bastions of coolness.

Their presence generates a certain funky vibe that appeals to the third phase of the gentrification sequence: (3) “bourgeois bohemians,” to use David Brooks’ term. Free-spirited but well-educated and willing to strike a bargain with middle-class normalcy, this group is skillfully employed, buys old houses and lovingly restores them, engages tirelessly in civic affairs, and can reliably be found at the Saturday morning farmers’ market. Usually childless, they often convert doubles to singles, which removes rentable housing stock from the neighborhood even as property values rise and lower-class renters find themselves priced out their own neighborhoods. (Gentrification in New Orleans tends to be more house-based than in northeastern cities, where renovated industrial or commercial buildings dominate the transformation).

After the area attains full-blown “revived” status, the final cohort arrives: (4) bona fide gentry, including lawyers, doctors, moneyed retirees, and alpha-professionals from places like Manhattan or San Francisco. Real estate agents and developers are involved at every phase transition, sometimes leading, sometimes following, always profiting.

Native tenants fare the worst in the process, often finding themselves unable to afford the rising rent and facing eviction. Those who own, however, might experience a windfall, their abodes now worth ten to fifty times more than their grandparents paid. Of the four-phase process, a neighborhood like St. Roch is currently between phases 1 and 2; the Irish Channel is 3-to-4 in the blocks closer to Magazine and 2-to-3 closer to Tchoupitoulas; Bywater is swiftly moving from 2 to 3 to 4; Marigny is nearing 4; and the French Quarter is post-4.

Locavores in a Kiddie Wilderness

Tensions abound among the four cohorts. The phase-1 and -2 folks openly regret their role in paving the way for phases 3 and 4, and see themselves as sharing the victimhood of their mostly black working-class renter neighbors. Skeptical of proposed amenities such as riverfront parks or the removal of an elevated expressway, they fear such “improvements” may foretell further rent hikes and threaten their claim to edgy urban authenticity. They decry phase-3 and -4 folks through “Die Yuppie Scum” graffiti, or via pasted denunciations of Pres Kabacoff (see Figure 2), a local developer specializing in historic restoration and mixed-income public housing.

Phase-3 and -4 folks, meanwhile, look askance at the hipsters and the gutter punks, but otherwise wax ambivalent about gentrification and its effect on deep-rooted mostly African-American natives. They lament their role in ousting the very vessels of localism they came to savor, but also take pride in their spirited civic engagement and rescue of architectural treasures.

Gentrifiers seem to stew in irreconcilable philosophical disequilibrium. Fortunately, they’ve created plenty of nice spaces to stew in. Bywater in the past few years has seen the opening of nearly ten retro-chic foodie/locavore-type restaurants, two new art-loft colonies, guerrilla galleries and performance spaces on grungy St. Claude Avenue, a “healing center” affiliated with Kabacoff and his Maine-born voodoo-priestess partner, yoga studios, a vinyl records store, and a smattering of coffee shops where one can overhear conversations about bioswales, tactical urbanism, the klezmer music scene, and every conceivable permutation of “sustainability” and “resilience.”

It’s increasingly like living in a city of graduate students. Nothing wrong with that—except, what happens when they, well, graduate? Will a subsequent wave take their place? Or will the neighborhood be too pricey by then?

Bywater’s elders, families, and inter-generational households, meanwhile, have gone from the norm to the exception. Racially, the black population, which tended to be highly family-based, declined by 64 percent between 2000 and 2010, while the white population increased by 22 percent, regaining the majority status it had prior to the white flight of the 1960s-1970s. It was the Katrina disruption and the accompanying closure of schools that initially drove out the mostly black households with children, more so than gentrification per se.1 Bywater ever since has become a kiddie wilderness; the 968 youngsters who lived here in 2000 numbered only 285 in 2010. When our son was born in 2012, he was the very first post-Katrina birth on our street, the sole child on a block that had eleven when we first arrived (as category-3 types, I suppose, sans the “bohemian”) from Mississippi in 2000.2

Impact on New Orleans Culture

Many predicted that the 2005 deluge would wash away New Orleans’ sui generis character. Paradoxically, post-Katrina gentrifiers are simultaneously distinguishing and homogenizing local culture vis-à-vis American norms, depending on how one defines culture. By the humanist’s notion, the newcomers are actually breathing new life into local customs and traditions. Transplants arrive endeavoring to be a part of the epic adventure of living here; thus, through the process of self-selection, they tend to be Orleaneophilic “super-natives.” They embrace Mardi Gras enthusiastically, going so far as to form their own krewes and walking clubs (though always with irony, winking in gentle mockery at old-line uptown krewes). They celebrate the city’s culinary legacy, though their tastes generally run away from fried okra and toward “house-made beet ravioli w/ goat cheese ricotta mint stuffing” (I’m citing a chalkboard menu at a new Bywater restaurant, revealingly named Suis Generis, “Fine Dining for the People;” see Figure 2). And they are universally enamored with local music and public festivity, to the point of enrolling in second-line dancing classes and taking it upon themselves to organize jazz funerals whenever a local icon dies.

By the anthropologist’s notion, however, transplants are definitely changing New Orleans culture. They are much more secular, less fertile, more liberal, and less parochial than native-born New Orleanians. They see local conservatism as a problem calling for enlightenment rather than an opinion to be respected, and view the importation of national and global values as imperative to a sustainable and equitable recovery. Indeed, the entire scene in the new Bywater eateries—from the artisanal food on the menus to the statement art on the walls to the progressive worldview of the patrons—can be picked up and dropped seamlessly into Austin, Burlington, Portland, or Brooklyn.

Figure 2. “Fine Dining for the People:” streetscapes of gentrification in Bywater. Montage by Richard Campanella.

A Precedent and a Hobgoblin

How will this all play out? History offers a precedent. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, better-educated English-speaking Anglos moved in large numbers into the parochial, mostly Catholic and Francophone Creole society of New Orleans. “The Americans [are] swarming in from the northern states,” lamented one departing French official, “invading Louisiana as the holy tribes invaded the land of Canaan, [each turning] over in his mind a little plan of speculation”—sentiments that might echo those of displaced natives today.3 What resulted from the Creole/Anglo intermingling was not gentrification—the two groups lived separately—but rather a complex, gradual cultural hybridization. Native Creoles and Anglo transplants intermarried, blended their legal systems, their architectural tastes and surveying methods, their civic traditions and foodways, and to some degree their languages. What resulted was the fascinating mélange that is modern-day Louisiana.

Gentrifier culture is already hybridizing with native ways; post-Katrina transplants are opening restaurants, writing books, starting businesses and hiring natives, organizing festivals, and even running for public office, all the while introducing external ideas into local canon. What differs in the analogy is the fact that the nineteenth-century newcomers planted familial roots here and spawned multiple subsequent generations, each bringing new vitality to the city. Gentrifiers, on the other hand, usually have very low birth rates, and those few that do become parents oftentimes find themselves reluctantly departing the very inner-city neighborhoods they helped revive, for want of playmates and decent schools. By that time, exorbitant real estate precludes the next wave of dynamic twenty-somethings from moving in, and the same neighborhood that once flourished gradually grows gray, empty, and frozen in historically renovated time. Unless gentrified neighborhoods make themselves into affordable and agreeable places to raise and educate the next generation, they will morph into dour historical theme parks with price tags only aging one-percenters can afford.

Lack of age diversity and a paucity of “kiddie capital”—good local schools, playmates next door, child-friendly services—are the hobgoblins of gentrification in a historically familial city like New Orleans. Yet their impacts seem to be lost on many gentrifiers. Some earthy contingents even expresses mock disgust at the sight of baby carriages—the height of uncool—not realizing that the infant inside might represent the neighborhood’s best hope of remaining down-to-earth.

Need evidence of those impacts? Take a walk on a sunny Saturday through the lower French Quarter, the residential section of New Orleans’ original gentrified neighborhood. You will see spectacular architecture, dazzling cast-iron filigree, flowering gardens—and hardly a resident in sight, much less the next generation playing in the streets. Many of the antebellum townhouses have been subdivided into pied-à-terre condominiums vacant most of the year; others are home to peripatetic professionals or aging couples living in guarded privacy behind bolted-shut French doors. The historic streetscapes bear a museum-like stillness that would be eerie if they weren’t so beautiful.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, Delta Urbanism, Lincoln in New Orleans, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, and nolacampanella on Twitter.

--------

1 The years-long displacement opened up time and space for the ensuing racial and socio-economic transformations to gain momentum, which thence increased housing prices and impeded working-class households with families from resettling, or settling anew.

2 These Census Bureau race and age figures are drawn from what most residents perceive to be the main section of Bywater, from St. Claude Avenue to the Mississippi River, and from Press Street to the Industrial Canal. Other definitions of neighborhood boundaries exist, and needless to say, each would yield differing statistics.

3 Pierre Clément de Laussat, Memoirs of My Life (Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge and New Orleans, 1978 translation of 1831 memoir), 103.