Dispatches from Dream City: Zadie Smith and Barack Obama

I

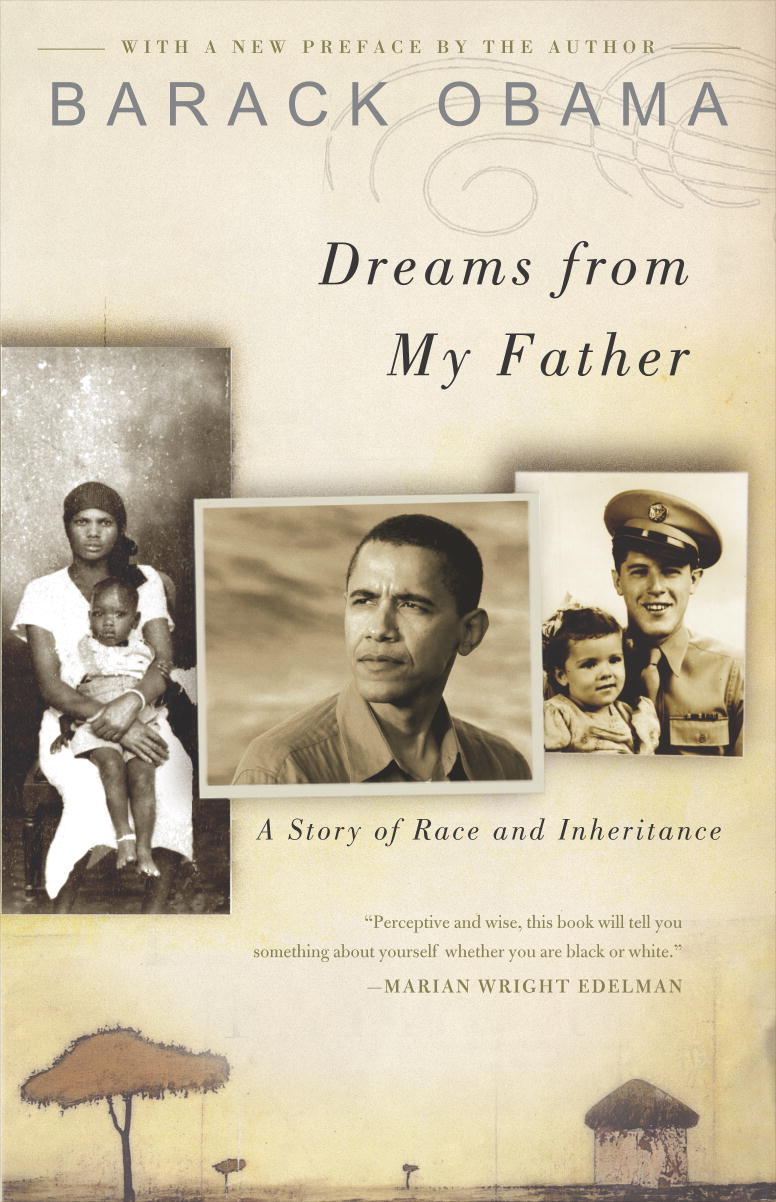

Reading and re-reading Zadie Smith’s spookily empathetic essay about Dreams of My Father and the natural linguistic flexibility of the biracial, upwardly mobile figure, the inevitable thought occurred to me: Is Zadie Smith the Barack Obama of literature?

Consider the parallels between the two: both are biracial (Zadie Smith had a white English father and a black Jamaican mother). Both are precocious strivers who came from somewhat déclassé origins and rose to become shining examples of their respective countries’ meritocratic aspirations (Zadie Smith grew up in a council flat, the English equivalent of a housing project, and received a scholarship to Oxford). Both give evidence of having been closer to their white parent. Both seem to promise liberation from the bad faith that has existed on both sides of the color line since the start of the post-civil rights era. Both are figures who because they smoothly speak the language of progressivism (in Smith’s case, the language of progressivism is the language of avant-garde literature and abstruse academic theory) appear–or in the case of Obama, appeared–less cautious and conservative than they really are. Changing My Mind is the title of Zadie Smith’s collection of what she calls ‘occasional essays;’ it might as well be titled ‘Only Connect,’ to use the credo of her beloved E.M.Forster’s Howards End–like Forster and like Obama, Zadie Smith is a builder of bridges and a reconciler of the seemingly irreconcilable.

There is a remarkable essay, “Two Directions for the Novel,” which is a kind of Beer Summit for contemporary fiction: on one side of the table is Joseph O’Neill, author of the Gatsbyesque 9/11 novel Netherland, on the other side is Tom McCarthy, writer of manifestos (still, after a century, a prerequisite for avant-garde credentials) and author of the astringently difficult novel Remainder.

It can be said that—

II

Let me interrupt my own rather tendentious exercise in extended parallelism for a second to make the case for why Zadie Smith matters. Here, this collection makes amply evident, is not just a first-rate writer, but a writer who is first–rate at everything she does. Changing My Mind is full of first-rate travel pieces energized with jittery nerves and telling details, first-rate capsule movie reviews which humorously make the case why movies are simultaneously unworthy of serious critical reflection and enrapturing, first-rate celebrity mash notes that give a disarming glimpse into the writer’s private pantheon, first-rate autobiographical memoirs that manage to be intimate and discreet at the same time, first-rate academic criticism that shows that Smith has the tools to be another Stephen Greenblatt. The obvious comparison is to the virtuosic all-arounders, writers like Joyce Carol Oates or John Updike. But unlike Oates, whose criticism reads like the slightly impersonal work of the perennial A-student, or Updike, who whether the subject was Doris Day, Borges, or the penis, often slathered every topic with the same lyrical impasto, Smith’s writing is intensely personal but at the same time fitted to the demands of its subject with a bespoke snugness.

Smith’s writing inspires not just the reader but the writer. For the would-be writer, reading someone like Nabokov is a shock-and-awe experience that leaves him feeling his talents might be better suited to say, real estate. The prose in Changing My Mind, despite the wide reading and deep intelligence it displays, has that disarming and encouraging quality as rare in a good writer as it is in a politician—the common touch.

The common touch: even the most mandarin of writers is not immune to attempting it. For James Wolcott, the attempt is displayed in his habit of incorporating up-to-the minute (and soon to be outdated) popular usages (like employing ‘genius’ as an adjective). For someone like George Will, it comes out in his groan-inducing public love for baseball, in pseudo-populist lucubration that gives the impression of a statue stiffly descending from its plinth to mingle with the alarmed populace.

Smith’s is a self-deprecating, confidence-sharing, distinctively feminine kind of approachability (a sex-specific trait, as playfully acknowledged by her book):

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve sat backstage with a line of novelists at some festival, all of us with red pens in hand, frantically editing our published novels into fit form so that we might go onstage and read them. It’s an unfortunate thing, but it turns out that the perfect state of mind to edit your novel is two years after it was published, ten minutes before you go on stage at a literary festival. At that moment every redundant phrase, each show-off, pointless metaphor, all the pieces of deadwood , stupidity, vanity and tedium are distressingly obvious to you.

Like another follower of Dickens, Martin Amis, she is at her funniest when she isn’t trying to be antically comic.

III

It is a truism that the critical writings of novelists are doubly interesting because they shed light not just on their ostensible subjects but on the novelists themselves and their struggles with age-old aesthetic problems. In fact, the struggle with aesthetic problems—which is synonymous with the struggle to write itself–is one that Smith chronicles with unusual frankness.

In her essay, “That Crafty Feeling,” a funny and candid exploration of the many strategies the novelist develops to trick herself into completing a long work of fiction, she describes the use of ‘scaffolding:’

Each time I’ve written a long piece of fiction I’ve felt the need for an enormous amount of scaffolding…The only way to write this novel is to divide it into three sections of ten chapters each…Or the answer is to read the Old Testament and model each chapter on the books of the prophets, Or the divisions of the Bhagavad Gita…Or Ulysses. Or the songs of Public Enemy…

If you are writing a novel at the moment and putting up scaffolding, well, I hope it helps you, but don’t forget to dismantle it later…

This is wishful thinking, of course–in most cases, the scaffolding cannot be dismantled without tearing down the building because it has become part of the edifice itself.

In On Beauty, Smith’s Forsterian novel, the scaffolding is most noticeable in the form of the multiple references to and borrowings from Howards End: like Forster’s novel, On Beauty is set in motion by an awkward, and quickly terminated, infatuation between the young adult children of two ill-matched families; instead of the seemingly impulsive gift of a house from a terminally ill older woman to a younger one, there is the gift of a valuable painting; instead of the novelist’s impressionistic musings on a concert of Beethoven’s’ Fifth, there is a writerly passage on the Mozart Requiem; instead of the awkward autodidact Leonard Bast, there is the striving rapper Carl; and so on.

Because On Beauty differs from Howards End in many ways (though it appropriates Forster’s cozy and insistent editorializing voice), the reader looks for a pattern to Smith’s borrowings, and realizes with a sense of disappointment that there is none. The knowing references—which seem simultaneously to be a tribute backwards to Forster and a postmodern nod towards what Kristeva called ‘intertextuality’– become a series of distractions, like those awkward ‘homages’ directors used to love to insert in their movies.

The canny Forster wrote that a lack of all-around intelligence is a sure sign of creative power, suggesting that excessive intelligence of the kind that Smith possesses might hobble the writer of fiction, and that hyper awareness is no guarantee that the writer will create a living, breathing work of art.

Smith has abundant gifts as a writer of fiction—a knack for characterization, a good ear for dialect and idiolect, a naturally dramatic imagination, a strong sense of the present—but her effort to triangulate between postmodernism and what a Leavisite would call the Great Tradition has not so far produced a successful work of fiction. In her first novel , White Teeth, the attempt to forge a style that marries the comic realism of Dickens’s with what the critic James Woods calls the ‘Hysterical Realism’ of Foster Wallace, Rushdie etc shows how ultimately irreconcilable these two styles are.

IV

But let’s return to Obama. In the essay “Speaking in Tongues,” originally a talk delivered shortly after Obama’s election, Smith discusses her acquired flexibility of voice, the consequence of imposing the Cambridge English voice “with its rounded vowels and consonants in more or less the right place” on the voice of her childhood home, working-class North London. She ruefully admits that the two voices have narrowed into one, the educated voice, and that people are in general suspicious of voice-shifters:

We feel that our voices are who we are, and to have more than one, or to use different versions of a voice for different occasions, represents, at best. A Janus –faced duplicity, and at worst, the loss of our very souls.

This leads to Shaw’s Pygmalion, nominally “the unambiguous tale of a girl who changes her voice and loses her self…undercut by the fact of the play itself, which is an orchestra of many voices, simultaneously and perfectly rendered.” Another orchestra of many voices is the skillful memoir of the new President, Dreams of my Father:

For Obama, having more than one voice in your ear is not a burden, or not solely a burden—it is also a gift.

She quotes Obama on his parents’ failed marriage: “I occupied the place where their dreams had been.” Occupying a dream space is the job of the movie star; another voice shifter was the Englishman Pauline Kael called The Man from Dream City, Cary Grant, who transformed his voice into a voice neither English nor American, neither posh nor working class. Everyone wants to Cary Grant, even I want to be Cary Grant, Grant was quoted as saying.

It is not hard to imagine Obama having that same thought;…hearing his name chanted by the multitude.

Everyone wants to be Barack Obama. Even I want to be Barack Obama.Obama was born in [Dream City]. So was I. When your personal multiplicity is printed on your face, in a almost too obviously thematic manner, in your DNA, in your hair and in the neither-this-nor-that beige of your skin—well, anyone can see you come from Dream City…You have no choice but to cross borders and speak in tongues. That’s how you get from your mother to your father, from talking to one set of folks who think you’re not black enough to another who figure you insufficiently white.

Speaking in one voice to an audience in Iowa and in another voice to an audience in North Philly, is not just a necessary talent of the politician, it is also a way of insisting on the multiplicity that many of us feel.

That Obama would publicly criticize the black community and incur the wrath of Jesse Jackson “goes to the heart of a generational conflict…concerning what we will say in public and what will say in private.”

Here, it’s probably worth contrasting the pronouncements on race by Smith and those of America’s perhaps most famous biracial literary artist, August Wilson. The enormous difference between Wilson’s scorched–earth statements—expressing solidarity with the notorious anti-Semite and black separatist Amiri Baraka, refusing to let a white director film his play Fences, insisting, despite all the evidence to the contrary, that little has changed for Black Americans in the last fifty years—and the more equivocal views Smith gives can to some degree be accounted for by the difference between growing up in 1950s Pittsburg and 1980s North London. But the rest has to with a difference in temperament–the difference in temperament between the prophet and the mediator.

To me, the instruction “keep it real’”is a sort of prison cell…It made Blackness a quality each individual black person was constantly in danger of losing…

To keep it real means to speak in one voice, adhere to one set of prohibitions, which seems absurd, “not because we live in a post-racial world-we don’t–but because…black reality has diversified.”

For reasons that are obscure to me, those qualities we cherish in our artists we condemn in our politicians, In our artist we look for the many-colored voice, the multiple sensibility…the lack of allegiance in Shakespeare’s art…allowed him to do what civic officers and politicians can’t seem to: speak simultaneous truths.

Yes, but the lack of allegiance in politics means something different than lack of allegiance in art, doesn’t it?

Smith concludes on a cautious note of admittedly naïve optimism:I believe that flexibility of voice leads to a flexibility in all things. My audacious hope in Obama is based, I’m afraid, on precisely such flimsy premises.

V

Flexibility of voice—or a good prose style, for that matter—is no guarantor of a good president. Lincoln had, like Obama, a wonderful y expressive prose style and a terrific sense of humor. Grant, by some estimates our greatest writer-president, was a disaster in office.

Almost halfway into Obama’s term, there are few people left who cherish the audacious hope Smith so eloquently expressed. When society has abandoned the center, and with it the belief in mediation, in compromise, in building bridges, in civility, then the fate of the mediator is not to bring opposites together but to be hated by both ends of the spectrum. Two years in, Obama looks–despite his self-awareness, his energy, his wit his nimble intelligence—less and less like Lincoln and more and more like Jimmy Carter.

It seems more likely every day that Obama’s legacy will be not for what he succeeded or failed to do in office, but for a work of the imagination; I don’t mean Dreams of My Father, though it’s possible that book will still be read when Obama is just a memory–I mean the presidential campaign. The campaign was as cynically crafted as any of Karl Rove’s, as full of wooly promises and focus-group tested buzzwords as any in recent times (in the saloon across the street from where I work, patrons who watched the presidential debates on the TV above the bar were given a free shot every time a candidate used the word ‘change’). Yet the campaign’s greater meaning—that if we don’t live in a post–racial America, large groups of Americans ardently wish that we did—will not be forgotten.

VI

Literature, of course, is different from politics. Few politicians can succeed in the long term without a broad consensus and a firm political identity. A writer, though, can change and change, and also fail and fail, and still find a way to seep into posterity. The canon is full of failures—works of literature that were ignored` in their own time and large parts of which are unreadable, awkward, wooly, obscure, lost in the fog of history.

VII

In ‘Two Directions for the Novel’, which is, like most of the literary essays in this collection, a winningly transparent act of self-persuasion, Smith suggests a Third Way for the bewildered novelist, “the path hewed by extraordinary writers claimed by both sides [i.e., the traditionalists and the avant garde]: Melville , Conrad , Kafka, Beckett, Joyce, Nabokov.”

VIII

“Much of the excitement of a novel lies in repudiation of the one written before,” Smith writes in ‘That Crafty Feeling.’ She continues,“My God, I was a different person!” “I think many writers think this, from book to book. A new novel, begun in hope and enthusiasm, grows shameful and strange soon enough. After each book is done, you forward to hating it (and you never have to wait long); there is a weird, inverse confidence to be had from feeling destroyed, because being destroyed, having to start again, means you have space in front of you, somewhere to go.”

Perhaps that path is the road to Dream City: the space where the writer doesn’t’ t self-consciously try to build a bridge between Forster and Wallace, but tricks herself into forgetting about both of them.

* * *

John Broening’s Column Note.

—John Broening is a chef and writer based in Denver, Colorado. His work has appeared in the Baltimore Sun, the Baltimore City Paper, Gastronomica, Edible Front Range, and the Denver Post, for whom he writes a weekly column about food.