The women bringing

solar power

to Sierra Leone

An Indian college has trained 12 Sierra Leonean women to become solar engineers as part of a drive to bring electricity to rural communities

Graduate Yatta Gambai, from Gimadama village, Kenema district, plugs a mobile phone into a solar charger. Photograph: Meena Bhandari

Graduate Yatta Gambai, from Gimadama village, Kenema district, plugs a mobile phone into a solar charger. Photograph: Meena BhandariA group of 12 women from villages in Sierra Leone is in the frontline of a battle to bring solar-powered electricity to rural communities. No small feat, given that rural Sierra Leone is not connected to power.

The women were all trained at Barefoot College in Tilonia, Rajasthan, in western India. They are now back in Sierra Leone assembling 1,500 household solar units at a new Barefoot College in Konta Line village, Port Loko district, which is to be formally opened next month. They sit at long wooden tables fitting tiny coloured resisters to circuit boards – heads tilted, deep in concentration, as smoke puffs up from their soldering irons.

The women are all either illiterate or semi-literate – they used to be subsistence farmers, living day-to-day like millions in Sierra Leone. But now they are proud graduates, having travelled 6,000 miles to India to learn – in the women's words – "how to make light from the sun".

"The idea of solar was so surprising that I had to be a part of it," says Mary Dawo from Romakeneh village.

"Snakes, rodents, reptiles and biting insects crept and crawled into our homes with the dark at 7pm. Children couldn't study, and we couldn't relax, socialise or plan our lives after a long day's work," says Fatmata Koroma from Mambioma village.

The Barefoot College in Sierra Leone is the first in Africa. It will enrol up to 50 students on four-month residential courses in solar engineering. The Sierra Leone government has invested about $820,000 in the project. Though the college is funded by the government, the women hope they can run it independently, in what they describe as the "Barefoot way". The solar equipment the college runs on, and the equipment for 10 villages, was provided by the Barefoot College in India, and the initial training was sponsored by the Indian government as part of its south-south co-operation programme.

"In India, the first problem was vegetarian food," says Koroma. "The desert was too hot and everything was different. But, within months we could assemble circuits and construct systems. Anything was possible after that."

The graduates now live in the college hostel, where they will stay until they have trained their replacements "for the service to our villages and our country", says Nancy Kanu. She was in the first female batch of students to train in India, in 2007, the same year that Konta Line village, where she's from, was declared the first solar village. She is now chief solar engineer. "I teach full-time, but I'm on call – even at night – to fix a fuse, change a bulb or charge a phone," she says.

People interact differently now in Konta Line, says Aminata Kargbo. "People socialise more – they're nicer," she says. The advent of solar energy has saved the village about $1,000 in candles and kerosene so far; money that is being kept for the upkeep of solar equipment.

However, the solar units are expensive [$500-$800] and far beyond the reach of most rural households. "There's a 45% import tax … You need electricity to manufacture solar equipment here," says Idriss Kamara of the Safer Future Youth Development Project. The local NGO tackles the country's 60% youth unemployment, training people in vocational skills, including solar. But, Kamara says, few solar trainees find work because hardly any households use it. The government says it is looking to reduce the tax so benefits are passed on to customers and access to solar power increases.

However, while Sierra Leone's government supports the Barefoot College project, people have wider energy needs, says Yvette Stevens of the ministry of energy and water. "We are developing a broader rural energy programme focusing on community, productive and social needs," she says. Renewables such as solar, biofuels and hydro form the basis of this programme, supported by an upcoming World Bank project. "There's a lot of donor money for renewables now, given their impact on climate change," says Stevens. The government envisages local solar systems will provide power for clinics and schools, and for "water pumps, communal television, and computer centres", she explains. Energy is not set out as a separate MDG, but it's vital in meeting them, she says.

Sierra Leone is still catching up after the lost years of the decade-long civil war that wiped out the country's fragile infrastructure. More than 60% of people (about 3.6 million) live rurally. Few can afford generators. Even in urban areas, more than 90% of people go without power.

A recent World Bank report states that electricity is Sierra Leone's most daunting infrastructure challenge. This, despite the new Bumbuna hydropower plant, which has improved the situation in the capital, Freetown, a little during the rainy season, providing nearly half the city's demand. Nevertheless, rural areas lag far behind. Sierra Leone records 46 days of power outages a year, which is four times higher than in other low-income African states.

They may be a small part of a bigger strategy, but Sierra Leone's Barefoot women are thinking about the future. "Once these units are installed, I think we'll need an investor to manufacture solar units here to make them affordable for everyone," Barefoot College graduate Kanu says. "There's nothing we can't learn now to make our lives better. We have the power to change our villages."

__________________________

A Wearable Flexible

Solar Panel Vest

This is a proposed way to maximize the usage and efficiency of the KVA Flexible Solar Portable Kit by Dominic Wanjihia. Dominic was awarded one of the Flex Kits at the recent Maker Africa Faire in Accra after showing off some amazing new ideas.

One of the cheapest form of transport in Kenya is the “Boda Boda” literally meaning “Border-to-border”, a bicycle ride from one countries boarder immigration offices through no-mans land to the immigration offices of the bordering country customs office.

This mode of transport is non discriminatory and is used by people of all walks of life. from school children, market goers, workers, business persons, etc. The popularity is partially due to the speed and convenience as one does not get stuck in traffic. In the Lake basin town of Kisumu there are estimated to be over 500,000 BodaBoda’s. In the whole county, in excess of 1,500,000

The BodaBoda rider normally works from as early as 4.30a.m. to as late as 10.00p.m. depending on security in the area. He relies greatly on his mobile phone for clients to call for his services. His peak cycling times are early morning, lunch hour and dusk as persons head home from school and work. Translates to 4 – 5 hours in total daily riding time.

Due to the lack of know how and the complexity of electronics, the lack of power storage (i.e. a battery, and the cost) the Cycle dynamo is only effective for charging items and lighting while he is riding. Also, due to space or lack of, cost, insecurity and theft, attaching “Hard” Solar panels to the bikes has never been a viable sustainable option.

However, with the introduction of the Flexible Panels I believe wearing the panels on his back eliminates all these constraints. It also means he is generating power from sun-up to sun-down, an average of 12 hours a day.

Attaching the flexible panels on his back ensures:

- His phone is always charged guaranteeing customer accessibility

- He has light at home from the LED’s so saves on heavy power bills

- He always has an emergency light with his – LED

- The panels will not get stolen

- One can also offer charging facilities to client being carried

Other users

The BodaBoda is not the only potential user of the Flexible Panel by wearing it. Anyone spending long hour’s outdoors is a candidate. The farmer, fisherman, hawker’s and peddlers, city council outdoor workers, tourists, campers and hikers – just to mention a few.

Attaching the Panel

It can be attached in a variety of ways. Velcro, Pop Buttons or simply attach Rucksack like straps so it can be worn with any garment. In the latter case the small pouch containing the controller and battery is attached to the back of the panels with Velcro.

If you would like to get in touch with Dominic, you can reach him at dwanjihia@yahoo.com or by phone at +254722700530

Hacking the FLAP Bag!

This is part of an ongoing series of posts on the FLAP bag project, a collaborative effort by Timbuk2, Portable Light and Pop!Tech. We at AfriGadget are helping to field-test these bags that have solar power and lighting on them, and get interviews of the individuals using them.

I was a little concerned when 5 of the 10 FLAP bags that I received before I left for Africa weren’t assembled – just fabric, thread and electronic components. It would mean that I’d have to find tailors in each country to put them together. However, it turned out that one of my favorite parts of getting the FLAP bags to Africa has been working with the tailors.

What I end up doing is explaining the bag and how it works, then showing them the one that isn’t put together and asking them if they would be willing to duplicate. If so, they can keep the bag. Then, I offer a challenge, taking the two-paneled Portable Light Kits from KVA, I then ask them if they could make something from their own materials, with their own designs, from it.

They had 2-3 days to come up with an idea, pick the fabric and create the bag. I then bought it from them for $20.

Kenya Bags

Ghana Bags

It should be noted that the gentlemen working on these had very little time to come up with their ideas and then implement them, as I was very much on the move. The local cloth use in Ghana was amazing, and I only wish the Kinte cloth (orange) one was done with real Kinte cloth instead of a print. The Kenyans used more ordinary fabric, but they were ingenious with the details around use, size and practicalities around security.

To really see the creativity at play in the Kenya bags, you have to either see them in person, or a video. Since I don’t have the bandwidth for a video now, that will have to come later.

A Kenyan Designer and Tailor

with the FLAP Bag

This is part of an ongoing series of posts on the FLAP bag project, a collaborative effort by Timbuk2, Portable Light and Pop!Tech. We at AfriGadget are helping to field-test these bags that have solar power and lighting on them, and get interviews of the individuals using them.

Jericho Market is a small market tucked away behind the industrial area in Nairobi, Kenya – near to Buruburu. It’s where you can find a lot of artisans who work on cloth-based projects, from clothes to bags and everything in between. I took off with David Ngigi, a local videographer friend of mine, to see who we could find. I brought two of the unstitched bags, two Portable Light kits and one completed bag as a sample.

The first person we spent time with was Joseph Muteti, a soft-spoken, 18-year veteran of the tailor trade in Nairobi. He specializes in making school bags for children and messenger-type bags. His bags are generally sturdy, with an added flair of embroidery to set them off for his customers.

Next up was Stephen Omollo, an energetic young designer who works on textiles ranging from shirts to bags. Style and usability are both important to Stephen, and his primary desire is to create items that people are proud to wear.

Interestingly, both Stephen and Joseph thought the bags were too large. Stephen wanted to cut in half, and Joseph by about a third.

Giving the FLAP bag

to some electricians

This is part of an ongoing series of posts on the FLAP bag project, a collaborative effort by Timbuk2, Portable Light and Pop!Tech. We at AfriGadget are helping to field-test these bags that have solar power and lighting on them, and get interviews of the individuals using them.

Hayford Bempong and David Celestin are electricians at Accra Polytechnic, who I wrote about last as they hadfabricated an FM radio station from scratch and used it at Maker Faire Africa. Hayford and David seemed like just the type to take a look at the bag and really determine its use. Being college-level students, they have a different type of lifestyle than many, and that might mean more ideas and thoughts about what the FLAP bag could be used for.

Electrical Students in Ghana take on the FLAP bag from WhiteAfrican on Vimeo.

True to form, they were not nearly as excited about the quality of the stitching, or the textiles used, but very interested in the internal electrical components. They were excited about the idea of a bag with an in-built solar panel, and were curious as to wattage and the ability use step-ups and inverters to make it even more useful.

One suggestion that they made was around durability of the electrical components, specifically they suggested that a metal box should be built around it. Life in Africa can be quite rough on gear, and the chance that someone will sit on, drop, or crush this part is quite high.

Mechanics and Tailors

This is part of an ongoing series of posts on the FLAP bag project, a collaborative effort by Timbuk2, Portable Light and Pop!Tech. We at AfriGadget are helping to field-test these bags that have solar power and lighting on them, and get interviews of the individuals using them.

I’d like to upload some of the video from today’s first big day in Ghana, but bandwidth considerations make that a little difficult right now. Instead, I’ll give an overview and show some pictures.

Mechanics

Henry Addo is a colleague of mine at Ushahidi, and he’s also the Ghanaian representative who is helping me hand out the bags, do interviews and have fun… He’s also a motorcycle rider, so I made sure to pack my helmet before leaving. We set off in search of likely prospects for both the FLAP bag project and Maker Faire Africa.

I started out on a 250cc Honda streetbike that made me feel a little like Bowzer in Mario Kart. Fortunately, our first stop of the day was at Henry’s local motorcycle street mechanic at which I saw a beautiful 600cc Yamaha Terere being fixed up. The owner happened to be there, and he was game for a 2-day swap (with about $10/day thrown in for good measure…)!

This was also the first place that we started showing off one of the assembled bags to gauge the kind of reaction that we would receive from people. We didn’t do any formal interviews here, but had a good time of questions and people came up with some interesting thoughts on the use of the bag.

The head mechanic absolutely loved it, recounting the many times he was traveling around Ghana and needed light at night to fix his motorcycles.

The real estate businessman wanted to know the cost, thinking he would buy one right now for $100 from us (for bragging rights). Though he thought there was a market for them in Accra, that the real buyers would be found in rural villages.

The used-goods businessman wondered what would happen to the solar system if you tried to wash it to clean the bag. I didn’t have an answer, but I said that I thought it would be durable.

Tailors

We ran all over town trying to find tailors of adequate skill to assemble the bags that had come in pieces. It turned out being a little bit of a challenge, but things took a great turn for the better and we found 2-for-1 going on in a market. Elijah and Mohammed both traditionally use West African cloth to make both jackets and bags, however, they were game for this challenge (especially as it scored them a free bag).

Both tailors spent a great deal of time examining the textiles used and they made comments about the quality level of the bag. Interestingly, they didn’t think they would use the bags that much themselves, but they did think that their wives would find them useful.

I did full interviews with both of them, and will upload those in the near future. Henry will be going back to them in 2-3 weeks to see what has happened with the bags and how they are being used.

Knowing that we wouldn’t find too many others that could make the bags from the pieces we had, we also wanted to challenge them to something even more interesting. We asked what they would do if we gave them a basic portable light kit (2 solar panels instead of 1) and tried to make a bag with it, using traditional cloth elements and no set design pattern. Both decided to give that a try as well, with the caveat that some material would be hard to find, and we’ll report back on the outcome.

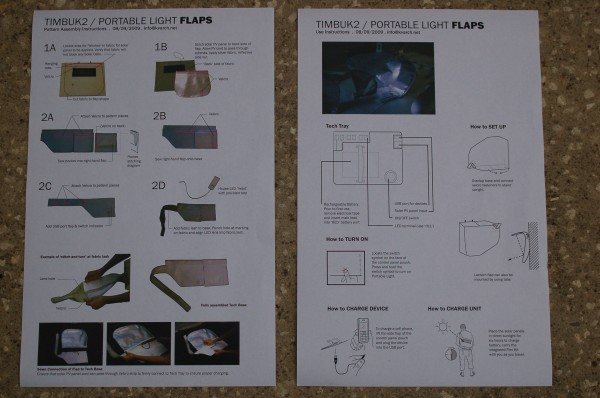

The FLAP buckets and assembly

This is part of an ongoing series of posts on the FLAP bag project, a collaborative effort by Timbuk2, Portable Light and Pop!Tech. We at AfriGadget are helping to field-test these bags that have solar power and lighting on them, and get interviews of the individuals using them.

Day 2: The buckets arrive

This is a continuation of yesterday’s starting video diary, where I received the flaps to the FLAP bag. Saturday morning the package from Timbuk2 was on our doorstep waiting to be opened. The bottom part of the bags had arrived, but there were a few surprises in store for me…

The FLAP bag buckets and assembly from WhiteAfrican on Vimeo.

Next stop Accra, Ghana. I hope that all the kits arrive in one piece, and will start to put them to use as soon as I can.

The FLAP Bags Arrive

This is part of an ongoing series of posts on the FLAP bag project, a collaborative effort by Timbuk2, Portable Light and Pop!Tech. We at AfriGadget are helping to field-test these bags that have solar power and lighting on them, and get interviews of the individuals using them.

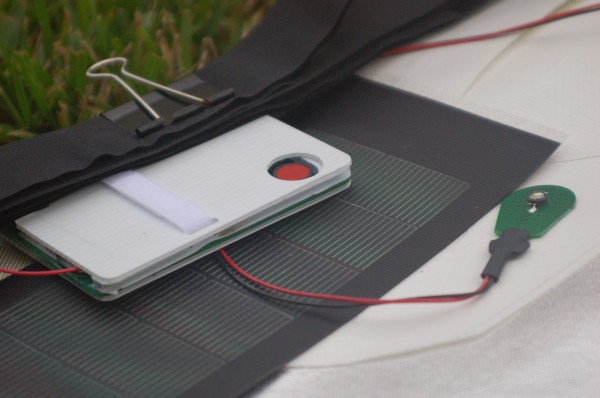

Day 1: The flaps arrive

The FLAP bag kits started to arrive Friday evening. The buckets (bottom part of the bag) from Timbuk2 had not yet been delivered at this point, so all I had was the flaps.

The FLAP bags start to arrive from WhiteAfrican on Vimeo.

Tune in for part 2 later… in the meantime, some pictures: