http://inktalks.com Storyteller d'bi.young anitafrika uses the art of dub poetry to weave a story of childhood sexual abuse and HIV in this beautifully intense performance.

ABOUT INK: INKtalks are personal narratives that get straight to the heart of issues in 18 minutes or less. We are committed to capturing and sharing breakthrough ideas, inspiring stories and surprising perspectives--for free! Watch an INKtalk and meet the people who are designing the future--now.

http://INKtalks.com Follow INKtalks on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/INKtalks

Like INKtalks on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/INKtalks

Subscribe to our channel: http://www.youtube.com/user/INKtalksDirector ABOUT D'BI.YOUNG ANITAFRIKA:

d'bi.young anitafrika, affectionately know as d'bi. is an internationally celebrated Jamaican dubpoet, monodramatist and educator whose socially-conscious performance art works have made an indelible mark upon the global psyche. After moving from Kingston Jamaica in 1993, she exploded onto the Canadian theatre scene in 2001 as the unbelievable storyteller in 'da kink in my hair' which played at London's Hackney Empire Theatre in 2006 and has toured globally. Since then d'bi. has written 8 plays: solitary, yagayah (published), androgyne (excerpt published), she, domestic and the sankofa trilogy, featuring the award winning monodramas blood.claat, benu, and word! sound! powah! Her groundbreaking Biomyth Sorplusi Method assists artists worldwide with developing their personal integrity in art-making and is being practiced in over 8 countries. Ms. young's work has been produced at Canadian theatres: Passe Muraille, Buddies in Bad Times, GCTC, Firehall and internationally at London's Free Word Centre, Barcelona's CCCB, Havana's Teatro Nacional, Cape Town's City Hall, India's Counter Culture, Belfast's Metropolitan Arts Centre, Kingston Jamaica's Edna Manley College and Barbados's Queen's Park. For more about d'bi.young: http://inktalks.com/people/dbiyounganitafrikad'bi young

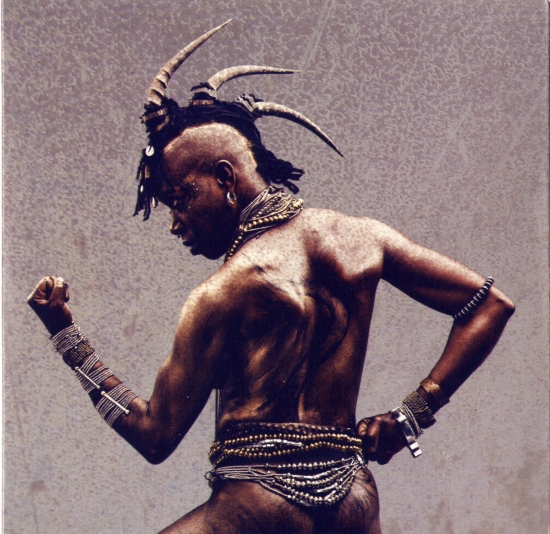

Photo credit: noncedo charmaine, (as it appears on the CD 333, design by James Kachan).

By Jason Selman

On Dec. 6, 2011, Montreal’s Kalm Unity Vibe Collective had the pleasure of having d’bi young as its special guest. The occasion was the release of her album 333 and tour in support of it. Ms. Young performed solo tracks from the album and then was backed by the Kalm Unity band. As always d’bi gave an awesome performance. Afterwards I sat down with her surrounded by friends to conduct the following interview.

litlive.ca: What does Montreal mean to you as an artist?(‘Police & Thieves’ by Junior Murvin is playing in the background)d'bi young: Montreal is the place where I moved from my adolescence into my young adulthood, and that’s really crucial because at the time when I was here (I came at nineteen, and left when I was twenty-two) those three years were crucial in helping me to locate myself not only within Canada but to locate myself within a Jamaican reality. I remember my friend Dave Austin being instrumental in encouraging me to re-investigate the roots of Dub poetry and to uncover and recover the fact that I was raised by elders of Dub poetry, veterans of Dub poetry, pioneers of Dub poetry, which I seemed to have forgotten on my move to Canada. Canada, when you’re coming from the outside at fifteen has the potential to really confuse you because of the assimilation that is forced down your throat: the cultural assimilation, the linguistic assimilation. And so I went through a process of losing myself and then finding myself through living in Montreal and moving among a young group of politicised artists including some of (I feel), the layers of the foundation of poetry in Montreal that includes you, Jason. There are many, many people I can think of who were around at that time who made an incredible impact on my work as a Dub poet. People like the Neudorfers [David and Joseph], people like Naila [Keleta-Mae], people like Jah Sun who was playing in a different band at that time and many, many more people. Alexis O’Hara was around, mentoring me and helping to create a space for me to do my work. So Montreal has a really special and emotional place in my heart because what I’m doing now is so much an outgrowth of this city.

litlive.ca: What separates Dub from the rest of reggae of the movement? Both stylistically and philosophically? (‘Reggae Got Soul’ by Toots & the Maytals can now be heard)

d'bi young: Let’s say Reggae music is a part of a trunk. As that tree grows, on the branches of that tree are the specific mediums in which you tell stories. So Dub poetry is one of the branches, so is Hip Hop, Slam or whatever else you want to consider the different mediums. Dub poetry grows out of Reggae; it cannot be separated from its parents. Dub is a child of Reggae music, so is Dancehall, so is Hip Hop. What makes Dub different from let’s say Dancehall and Hip Hop, which are its cousins is that Dub has some very clear principles which include but are not limited to its political content and context. Dub prides itself on locating itself within the centre of the community where the people gather and it reflects what the people are going through. Also, Dub coming out of the village is spoken first and foremost in the nation language of the people. Initially that nation language was Jamaican but since Dub is now an international form what it prides itself is being spoken in the nation language in of the people who are speaking it. Another principle of Dub is its commitment to rhythm and using rhythm as a tool of communication. As we know music has a potential to speak to people in a way that words are limited, so Dub even though it’s heavily word-based is also heavily music-based because it understood coming out of that oral African storytelling trunk that music has a potential to move people in ways that words can be limited. And then the final principle that I’ll mention is performance. Dub is a storytelling poetry and storytelling works best when the storyteller is involved in the process of telling their story physically, energetically, vocally and in any other way (spiritually) that they can use to tell the story so that the performance is all about the mind, body, spirit, word, etcetera. Word, sound, have powa.

litlive.ca: What have you learned from your trips / work in South Africa? How has it transformed you as an artist?(‘Slavery Days’ by Burning Spear is the current selection)

d'bi young: South Africa is a very complex place, like everywhere else. But I mention that because South Africa is now about twenty years out of its legitimized apartheid system. Now we here in North America, supposedly slavery ended in the 1800s, and as we can see more than a century later clearly slavery is still real. So that means to say that looking at apartheid twenty years down the line, twenty years is just not a long time. So you go South Africa and it’s really quite incredible the ways in which the Black people of South Africa are suffering. One has to ask the question, what changes have come about in twenty years and who has benefitted from those changes? And those are the questions that I’m asking because what I see around me is the same kind of inequities that exist in every country that considers itself to be post-colonial. It takes a long time to change and because apartheid is no longer legally on the books maybe many people have relaxed and feel that the struggle is over but in fact the struggle is only just begun. So that’s the dichotomy that exists there. Of course I also say what I’m saying from the place of I’ve only been in South Africa for a year so I don’t pretend to know everything and every little complex detail but inequity is inequity and you don’t haffi kno everyting to kno seh inequity is inequity. So there are many inequities and there are many people who are working on the ground to change those inequities but I think we must question what we are being sold here in North America about the government and about the changes that have come about. Because people are still suffering, in the millions.

litlive.ca: What does the completion and presentation of your Sanfoka Trilogy mean to you?(‘Tenement Yard’ by Jacob Miller is playing at the moment)

d'bi young: Well one, it means I’m old. Older. I am absolutely enjoying being able to look at the decade of work that the Sankofa trilogy represents. So those three plays: blood.claat, benu & word! sound! powa! are for me bio-myth theatre that I’ve been creating and the completion of that cycle means there are certain things that I can put to rest in order to begin other things. But it also means that word! sound! powa! which ends the trilogy is the play that talks the most about Dub poetry and about the birth of Dub poetry which I’ve always wanted to talk about in honour of my mother and those people who laid the foundation for us and I was finally able to do that. So it feels like a rite of passage, almost like I’ve only now graduated from my infancy in Dub poetry into I wouldn’t say eldership, but somewhere between infancy and eldership. And that’s really for me a very important step because it means now that this idea of mentorship is something that I can embrace fully. I’ve been doing that but having completed the trilogy now means, alright dat process done and you must represent as a teacher and I’m all about teaching. And learning, and teaching ... and learning ...

litlive.ca: Seeing that part three of your Sankofa Trilogy deals with a Jamaican Election in 2012, how do you feel about artists’ capacity to write the future into existence?

d'bi young: In word! sound! powa! - the Prime Minister who’s elected in 2012 is assassinated by the people and I think it’s crucial that as storytellers (which we all are), I think it’s crucial that we imagine the possibilities for change. I’m not saying that the best way to accomplish change is to go and assassinate the leader of your country; I’m just saying that I think that as storytellers we have to present a mirror to the people of possibilities that they may or may not consider and then not only those actions but what happens after that. So let’s say you do assassinate the leader of your country, what happens after that? What kind of organizing would you need to do and planning so that you don’t end up having someone else take power who then falls in love with power and who does the same thing that the person that you just assassinated would have done anyway, which is a cycle that we see repeating itself. So many revolutionaries, we fight the revolution, then we get into power and then we become despots ourselves, we become dictators, we doh wan’ share the powa, we see it over and over again. So it’s not just about taking out the people who we consider problematic, it’s also coming up with a good, good plan about how not to reproduce those actions.

litlive.ca: Where would you like to be artistically in twenty years?

d'bi young: In twenty years I would like to have a very well rounded international arts centre that’s somewhere on the African continent in sunshine. A place that has sunshine 24/7. On this compound we have a greenhouse, we have three or four wells where we can get clean running water, it’s completely solar powered and it’s sustainable in its development. People live there on and off, some people live there year round. People study there from different parts of the world, we have storytellers who come from different parts of the world to teach there and it’s a cyclical system of producing storytellers who then go out into the world and go to their own countries and villages to do the same model. I would be a part of a counsel of people who run this very elaborate circular arts education compound.

via litlive.ca