Film: "A Bend in the River"

- A London story of Migration,

Multiculturalisme and

the River Thames

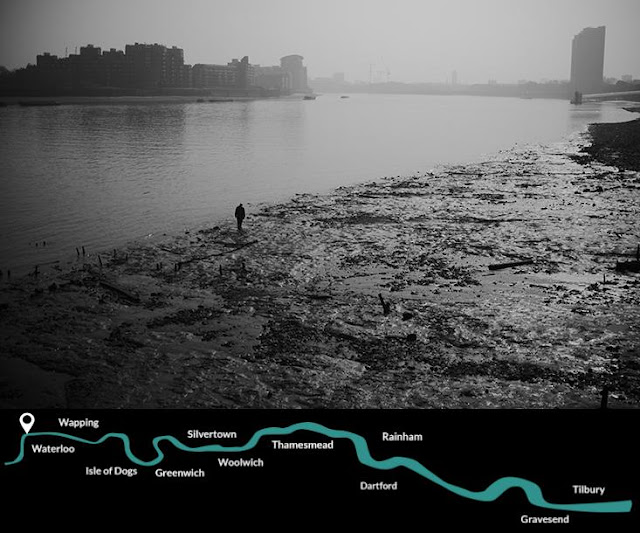

British writer Caryl Phillips invited photographer Johny Pitts to create the film/geographical slideshow "A Bend in the River". It eventually concluded in Tilbury, the Thames dockside some 30 miles away, where, between 1948 and 1962, ships arrived carrying immigrants from Britain’s former colonial territories, hastening the country’s transformation into a multi-cultural, multi-racial society.

Watch the film at The Space . And check out more or the project at A Bend in the River.

The film is based on Caryl Phillips's essay "A bend in the River", which he wrote for the artistic project "A Room for London".

GO HERE TO VIEW MAKING OF "FROM A BEND IN THE RIVER" VIDEO

For the project he stayed for four days in a one-bedroom installation, in the form of boat, on top of the Queen Elizabeth hall at the Southbank Centre in London.Some snippets of Phillips's essay

"But preconceptions are powerful, and we often hold on to them long after reality has intervened. Between 1948 and 1962, over 250,000 West Indians arrived in Britain. British citizens clinging to suitcases, gaudy hats, and with their passports of belonging tucked neatly into their jacket pockets. They were coming to the motherland and their minds were full of images of the empire’s most important city. Marble Arch. Buckingham Palace. Hyde Park Corner. The images were iconic, and knowledge of them suggested participation. A shared history. Possessing these images – being able to recognize these places and, most importantly, talk about them with the authority of an insider - would surely produce a happy encounter with Britain. These early West Indian migrants arrived in Britain holding on to their preconceptions as tightly as they held on to their luggage.

Over fifty years later, many of these original pioneer migrants are still living in London. We know what these migrants expected because their testimony is preserved in audio archives and in documentary films. We also know what they expected because of the literature of the period, and perhaps the most evocative, and brilliant, example of this literature is Samuel Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners, first published in 1956. Selvon’s main character, Moses Aloetta, finds himself, at the end of the novel, standing by the same river that I’m now perched high above. Despite the evidence of discrimination, poverty, and heartbreak that Moses is forced to endure throughout the book, at the end of the novel our Lonely Londoner is unable to jettison his images of expectation. He stands gloriously still on the banks of the Thames knowing that he can’t help but love this city that has effectively rejected him and his kind, and somewhat ironically he comforts himself by lovingly recollecting London’s iconic images and locales."

...

"Britain, like most European nations, is not particularly open to hyphenation. We don’t talk easily of Jewish-Britons, or Afro-Britons, or Swedish-Britons, thus making it relatively easy to couple ones cultural traditions to national identity. Being British remains a largely concrete identity, quite well gated, and not particularly flexible. " Read the full essay at A Room for London.

__________________________

April 2012

Caryl Phillips

Resident from 21 - 24 April 2012.

"I had anticipated endless lines of people shuffling across bridges to the left and to the right with, as Eliot suggests, each man fixing his eyes before his feet and silently going about his business."

Photograph by Johny Pitts

Download as mp3 | Subscribe on iTunes | Hearts of Darkness version

A Bend in the River

Of course, it was T.S. Eliot who famously declared, ‘April is the cruelest month’ and how right he was. Four days ago, soon after I ascended in the slow, slow, lift to the roof of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, it became clear that the weather would soon be taking a cruel turn. High winds and lashing rain one minute; the next a hint of blue sky, a slither of sunshine, and then back again to high winds and lashing rain. One was tempted to call it ‘squally’ weather. Another word which sprang to mind was ‘marooned’ – high above London, high above the Thames, looking down on Europe’s largest city.

The first night was strangely eerie. It was a night punctuated by unfamiliar sounds. Screeching seagulls, wires stretching and singing, wood creaking and popping and snapping, the swishing backwash of water, and the occasional dull bass of a tugboat. And then the noises of the land; Big Ben counting off the hours, the dull hum of traffic on Waterloo Bridge, and garbage carts being noisily trundled across pavements below. And then I was rewarded with the drama of light crashing through the flimsy blinds and the dramatic announcement of a new day. I crawled out of bed and took in an extraordinary vista. A 180 degree view of London as she curves around the graceful bend in the river at the heart of the city.

It seems appropriate that I should have had T.S. Eliot in mind at the inception of my residency for in many ways it is Eliot’s vision of the Thames and the City of London that had been resonating most powerfully in my head when thinking of this short sojourn in the sky. In The Waste Land, Eliot - an American migrant to London - wrote memorably of the ‘Unreal City’ of London.

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Hardly cheery words, but that foggy poetic image of London was, strangely enough, what I expected to be gazing down upon. I had anticipated endless lines of people shuffling across bridges to the left and to the right with, as Eliot suggests, each man fixing his eyes before his feet and silently going about his business. But that’s not the London I saw before me from my elevated vantage point. The fog of the first half of the twentieth century has long gone, and I haven’t detected much shuffling; in fact, people appear to dash purposefully in all directions. These Londoners don’t look at all as though death has undone them. From the prow of my boat in the sky, exuberant and energetic London is clearly open for business and busy.

But preconceptions are powerful, and we often hold on to them long after reality has intervened. Between 1948 and 1962, over 250,000 West Indians arrived in Britain. British citizens clinging to suitcases, gaudy hats, and with their passports of belonging tucked neatly into their jacket pockets. They were coming to the motherland and their minds were full of images of the empire’s most important city. Marble Arch. Buckingham Palace. Hyde Park Corner. The images were iconic, and knowledge of them suggested participation. A shared history. Possessing these images – being able to recognize these places and, most importantly, talk about them with the authority of an insider - would surely produce a happy encounter with Britain. These early West Indian migrants arrived in Britain holding on to their preconceptions as tightly as they held on to their luggage.

Over fifty years later, many of these original pioneer migrants are still living in London. We know what these migrants expected because their testimony is preserved in audio archives and in documentary films. We also know what they expected because of the literature of the period, and perhaps the most evocative, and brilliant, example of this literature is Samuel Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners, first published in 1956. Selvon’s main character, Moses Aloetta, finds himself, at the end of the novel, standing by the same river that I’m now perched high above. Despite the evidence of discrimination, poverty, and heartbreak that Moses is forced to endure throughout the book, at the end of the novel our Lonely Londoner is unable to jettison his images of expectation. He stands gloriously still on the banks of the Thames knowing that he can’t help but love this city that has effectively rejected him and his kind, and somewhat ironically he comforts himself by lovingly recollecting London’s iconic images and locales:

‘Oh … [he says] to have said: "I walked on Waterloo Bridge," "I rendezvoused at Charing Cross," "Piccadilly Circus is my playground," to say these things, to have lived these things, to have lived in the great city of London, centre of the world. To one day lean against the wind walking up the Bayswater Road (destination unknown), to see the leaves swirl and dance and spin on the pavement (sight unseeing), to write a casual letter home beginning: "Last night in Trafalgar Square …"'

Selvon’s characters grapple with the symbolism of iconic London, and the protracted and frustrating nature of their struggle suggests deep and unresolved issues around questions of belonging and ownership in the Britain of the period. Landscapes are freighted with history and can suggest a national identity; they can also remain stubbornly standoffish and hold outsiders at bay.

For the past few days I have been witness to the silent muscular power of the river flowing beneath me, history emerging from its impenetrable depths. I have exchanged visions of Romans sailing up the Thames for Conradian visions of ships at anchor waiting for the fog to lift. I have contemplated contemporary images of immigrants sailing up the river and disembarking at Tilbury Docks, some way down river to my right. I have also looked out at the grandeur of the buildings; St Paul’s Cathedral, The Palace of Westminster, Somerset House, Waterloo Bridge, at the whole spread of the most familiar landmarks of the city laid out before me, and I’ve done so without feeling the same clamour for ownership that Moses so desperately desired. And, I might add, without feeling any of Eliot’s gloomy ambivalence.

However, gazing upon these iconic buildings I have found myself thinking, every minute of every day, about the enduring power of British history, and how we continue to struggle to distinguish the past from the present, the purely ceremonial from the essential, in a way which might enable us to move forward as a modern nation. Fifty years on from lonely Moses on the banks of the Thames, I’ve not been thinking of, and hoping for, ownership. I’ve simply been musing on the vexing problems of how to make the narrative of our history, as evidenced in the landscape and buildings, fit with the narrative of a twenty-first century, multicultural, multiracial, people. One would never want to dismiss the evidence of grandeur, achievement, and tradition as suggested by this landscape. But questions remain that go beyond the symbolic; just how relevant is the role of an established church in British life? The role of the monarchy? The desirability of an unelected upper house? I scan to the left, and back to the right, and then look down at the people on the streets and there seems to be disjuncture between the narrative on the streets and the narrative suggested by this particular view.

Such questioning seems to me to be part of the legacy of growing up in the second half of the twentieth century, during the years in which Britain lost an Empire and somewhat reluctantly began to reconfigure her sense of herself. These are the years in which Britain – kicking and screaming - became both multiracial and European. However, I had initially assumed that the writers of the first half of the twentieth century who grappled with these questions of identity and belonging under the full gaze of Empire must have had a harder time of it than those of us in the post-Empire world. But after these past few days up here in Mr. Conrad’s boat, I’m not so sure. Publicly questioning our history is a healthy development, but it remains nonetheless unnerving. However, doing so will lead us forward to a place where we might responsibly start to question the ever-changing criteria for membership of a nation – this nation - while remaining cognizant of the fact that there are among us, in early twenty-first century Britain, countless numbers of Moses Aloettas, of all backgrounds, who are metaphorically standing on the banks of the Thames and simply dreaming of belonging.

On my second day atop the Queen Elizabeth Hall, I crossed the river and went to the Embankment where I sought out Yvonne; an elderly Caribbean person who, for the past seven years, has established some sort of a home for herself on the banks of the Thames. Smart, intelligent, not addicted to drugs or drink, she lives in and around Victoria Embankment Gardens near the seventeenth-century Watergate which depicts the old water line of the Thames before the building of the Embankment. I found her on a bench, surrounded by a huge pile of bags and suitcases; in short, her worldly possessions. She was asleep on a bright Sunday morning and so I didn’t disturb her. Instead, I continued to wander up and down the Thames, taking a closer look at these buildings which signify a particularly powerful history, contemplating both their symbolic, and actual, significance in 2012 in this culturally hybrid city of London.

I eventually wandered back to Mr Conrad’s boat and sat out on deck and looked at the lights playing on the undulating blanket of water, which bestowed upon it a glossy patina of melancholy. And then I took out my copy of The Lonely Londoners and read the first few lines again, feeling the unease and ambivalence in the words.

‘One grim winter evening, when it had a kind of unrealness about London, with a fog sleeping restlessly over the city and the lights showing in the blur as if is not London at all but some strange place on another planet …’

That’s it, exactly, I thought; ‘some strange place on another planet …’ For so many people the possibility of their participating in the type of Britain that these buildings symbolically suggest, remains for them about as real as the possibility of their participating in lunar exploration. It’s not the fault of the buildings, of course, but it’s what the buildings suggest. Exclusivity; privilege; power. Cumulatively the evidence of the buildings forms a powerful narrative that for many is a narrative of rejection. Even if one did take the time to learn the actual and symbolic meaning of this resplendent view of the city, the confident narrative at the heart of the city might well still neither recognize you, let alone embrace you and take you in.

The fact is, Britain’s history as evident in the buildings along this particular stretch of river, suggests a tradition that no longer really squares with the Britain that we deal with on a daily basis. Britain is no longer exclusively Judaeo-Christian. English is not the only language we hear daily on the streets. The monarchy are not universally respected. And the upper house of our parliament could use some serious reform.

Britain, like most European nations, is not particularly open to hyphenation. We don’t talk easily of Jewish-Britons, or Afro-Britons, or Swedish-Britons, thus making it relatively easy to couple ones cultural traditions to national identity. Being British remains a largely concrete identity, quite well gated, and not particularly flexible. For the past four days I’ve gazed upon the most familiar and easily identifiable aspects of British identity, as evidenced in the buildings on this particular bend in the river, and wondered about the plight of those who wish to belong to this nation but feel, for whatever reasons, locked out by dint of nationality, gender, race, class or religion. And, of course, I’ve wondered about the situation of those who have belonged and then capitulated to some form of participation fatigue. The July 7th bombers, for instance. It seems clear that in our early twenty-first century the process of engaging with these vexing issues of British identity and exclusion has, if anything, become an increasingly urgent part of our social contract. Something which I feel would not have surprised either gloomy Eliot or tremulously anxious Selvon.

From the vantage point of my boat here on top of the Queen Elizabeth Hall on the South Bank of the river, I am witnessing iconic London; iconic Britain. What I’m gazing upon is the familiar, hugely exportable, and in a sense, very comfortable, public face of Britain. Soon after arriving on the boat, the suggestive rootedness, and un-selfreflective confidence of these buildings - for instance the self-conscious grandeur of the Savoy Hotel directly across the river - began to irritate me. Yesterday I finally gave up and jumped on a Thames Clipper and headed off down river in search of another vision of London. And of course, I found it. The historic buildings of Bankside and Shakespeare’s Globe, gave way to the Tower of London, and then the astonishing array of modern flats around the newly revamped Isle of Dogs. The Dubai like spectacle of Canary Wharf appears almost like a mirage, and beyond this there is the glory of Greenwich Palace and then the extraterrestrial vision of the O2 arena. And beyond this? Well, less development and a reminder of an earlier unregenerated Thames. I went in search of other visions of London and found many Londons which, on my return to my own little rooftop boat, made me feel slightly more comfortable with my iconically powerful view. After all, it’s just a view, right? One which carries the authority and weight of power, but no more representative of London than the Isle of Dogs or the underdeveloped wastelands beyond Greenwich. But tell that to the tourists. Or to Moses Aloetta standing motionless on the banks of the Thames and wanting to belong. But wanting to belong to this London on my gentle bend in the river, not those Londons to the east. To this idea of London and Britain that constitutes my view. Can it really be true that not all views are equal? And if this is the case, is it possible, or even desirable, to make the narrative embedded in the view of London that is spread out before me available to everybody in Britain? Not for the first time I’m glad that Mr Conrad’s boat has come equipped with window blinds.

This essay evolved into a new work, viewable on The Space, with photographer Johny Pitts, exploring the journey between A Room For London and Tilbury.

************

Caryl Phillips was born in St Kitts, West Indies, grew up in Leeds and was educated at Oxford. He has written numerous scripts for film, theatre, radio and television. He is the author of six novels: The Final Passage, A State of Independence, Higher Ground,Cambridge, Crossing the River, The Nature of Blood, and four works of non-fiction,The European Tribe, The Atlantic Sound, A Distant Shore and, published in September 2005, Dancing in the Dark.

He has also edited Extravagant Strangers: A Literature of Belonging and The Right Set: The Faber Book of Tennis. Phillips’ awards include the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize, a Guggenhein Fellowship, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize. He has taught at universities in Sweden, Singapore, India, Ghana, Barbados and the United States. He divides his time between London and New York City.

A London Address podcasts are in collaboration with the Guardian.

>via: http://aroomforlondon.co.uk/a-london-address/apr-2012-caryl-phillips%22