Frida Kahlo's Closet

is Opened After 58 Years

Unfortunately your browser does not support IFrames.

Imagine being in Frida Kahlo's childhood home and opening up a closet that has been locked for decades. Inside are hundreds of personal items – personal photographs, love letters, medications, jewelry, shoes, and clothing that still hold the smell of perfume and the last cigarette she smoked.

That is exactly what happened when Hilda Trujillo Soto, the director of the Frida Kahlo Museum opened the closets that had been locked since the Mexican artist's death in 1954. Inside were over 300 items belonging to Frida Kahlo, and now, a wide array of what was found is on display at the Casa Azul, the Frida Kahlo Museum in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City.

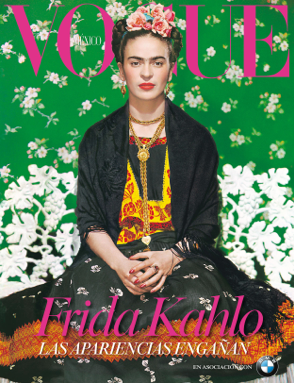

The exhibit, Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo, a collaboration between the museum and Vogue Mexico, brings to an end an elaborate 50 year scheme to keep private the intimate details of Kahlo's life. It started when she died in 1954, as a distraught Diego Rivera, the famous Mexican muralist and Frida Kahlo's husband, locked the doors to her closet and never let anyone enter for fear that the contents would be mishandled and ruined.

When he died in 1957 the task of protecting its contents went to a dear friend and patron, Dolores Olmedo, who promised him that the closet would remain unopened until 15 years after his death. She kept her word. In fact, she decided to keep the closet locked until her own death. And she lived a long life, passing away in 2002 at the age of 93.

Eventually, museum personnel decided it was time to look inside. And what a discovery. Art historians and fashionistas already knew Frida was unique and ahead of her time. But, what the items in the exhibit show are that despite the disabilities, the monobrow, and the violent depictions of the female anatomy in some of her paintings, Frida Kahlo was a bit of a girlie girl who wore makeup, used perfume and dressed up her prosthetic leg with a red high-heeled boot. Her clothing aimed for style and self-protection but it also made a statement, both political and cultural.

This was especially true of the Tehuana dresses Kahlo wore like a "second skin," said Circe Henestrosa, the exhibit curator. Colorful and carefully made by indigenous artisans, they were a tribute to the matriarchal Tehuantepec society whose women were traders, considered equals with the men. Tehuana's long skirts were also the perfect way for Kahlo to hide her ailments, including a polio-deformed leg she would eventually have amputated.

Latest issue of Mexican Vogue celebrates the exhibit.

"This dress symbolizes a powerful woman," Henestrosa said, adding: "She wants to portray her Mexicanidad, or her political convictions, and it's a dress that at the same time helps her distinguish herself as a female artist of the 40s. It's a dress that helps her disguise physical imperfections."

Frida painting her dad Guillermo's portrait in 1951.

It is a fashion exhibit built around those two themes – disability and ethnicity. The highlights include several of the Tehuana dresses, corsets that Kahlo wore to keep her damaged spine straight and fancy embroidered satin shoes. Her cat-eye style sunglasses and a baguette clutch purse are among the surprising personal items displayed in a glass cabinet.

In order to elevate the exhibit from simple costume into a fashion exhibit in collaboration with Vogue, the show also includes examples of how her style has influenced modern design. There are the corsets from Jean Paul Gaultier and Comme des Garçon's collections. And in the Givenchy dresses on display, designed by Riccardo Tisci, there are Kahlo-inspired flowers, white lace and cotton, reminiscent of a few key elements often found in her paintings.

Several other artists were brought on board to contribute to the exhibition including Dai Rees who created a leather corset inspired by those worn by Frida Kahlo and Angelo Seminara who used dyed hemp (using Frida's favorite colors) to create hair designs for the nine faceless mannequins wearing her clothing.

It's a small exhibit with the Casa Azul having just five rooms to show Kahlo's personal belongings. And it's a shame since the items that are shown spark a curiosity and hunger to know more about what Frida chose to wear and the style that has lived on so long after her passing. What else was in that closet?

Perhaps to satisfy that curiosity, the curators are planning on rotating parts of the exhibit in five months to show more of the items. The mannequins in one gallery will be switched into new looks and the cabinet of personal items that now includes shoes and jewelry will also be changed.

We can only guess which items they will choose to display – will we get to see all the photographs and love letters? – but ultimately it's the small items that are the most potent offerings: they are what bring her to life, and take us beyond the now familiar image of her self-portraits. From nail polish to medicine, the show's power comes from humanizing an icon and making her a woman we can all relate to.

Frida circa 1926, photo taken by her dad Guillermo.

Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo, a collaboration between the Frida Kahlo Museum and Vogue Mexico, opened on November 24th, 2012 and will run for a full year.