Girls for Gender Equity

Helps Girls Take Aim

at Sexual Harassment

Friday Jun 22, 2012 – by Tami Winfrey Harris

Friday Jun 22, 2012 – by Tami Winfrey HarrisCatcalls were such a common experience to Kayla, a youth organizer with Girls for Gender Equity (GGE), a Brooklyn-based, grassroots organization devoted to the development of girls and women, that she did not view those things as sexual harassment. In Hey Shorty, GGE’s guide to combatting sexual harassment in schools and on the streets, Kayla says, “It’s this thing that happens to you, because you’re a girl.”

Supporting young women of color in combating harassment is just one way that GGE enacts its mission. GGE and its allies are among those doing real work to help the next generation of women grow up strong and self-assured. According to its mission, GGE is addresses the physical, psychological, social and economic development of girls and women through education, organization and physical fitness.

Joanne Smith, group founder, says GGE arose from her work with young girls and the realization of how few outlets and services were available to them. Smith wanted to help protect girls from unsafe streets and provide a place where they “could express themselves and feel a sense of agency and freedom.”

The organization began working with New York City schools under the auspices of Title IX, a landmark amendment to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that most people associate with the emergence of girls and women’s sports in schools. But Title IX, currently celebrating its 40th year, has done so much more than make it possible for talented women to enter college on basketball scholarships. (Which, in itself, is important.)

No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

–Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 to the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Title IX addresses access to higher education; employment; math and science; career education; standardized testing; athletics; education for pregnant and parenting students; learning environments; technology and sexual harassment.

GGE began by offering sports and educational opportunities to girls seven to 12, but the organization, and its offerings, blossomed to include much more. Smith and the GGE team have provided an outlet where girls can see themselves as people of value, no matter their age, race, sexuality or socioeconomic status. Participants are developing their voices and critical thinking skills and they are becoming powerful agents of social change.

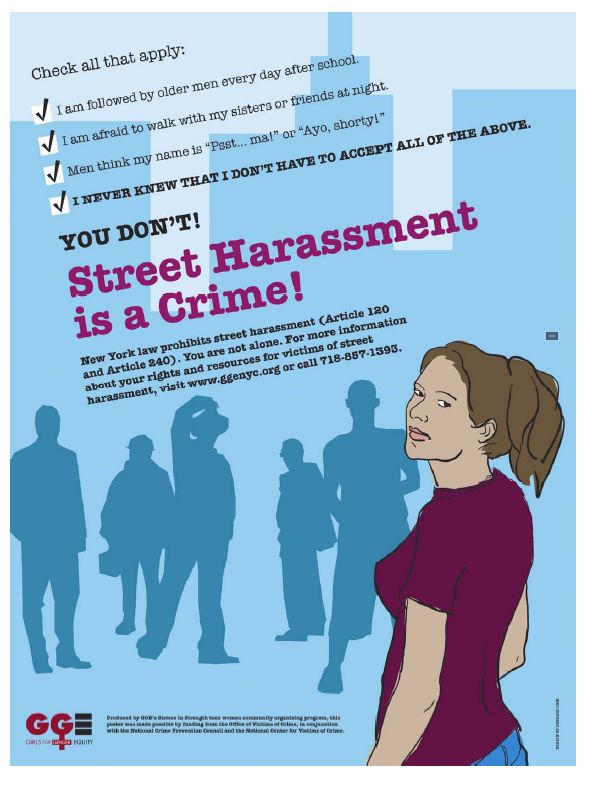

For instance, a group of young GGE participants, calling themselves Sisters in Strength, created a documentary called Hey Shorty (See a clip above) that addressed the verbal and physical assaults many girls face everyday as they travel between home and school. The movie won the Best Youth Documentary Award at the 10th Annual Roxbury Film Festival in Boston and, in doing, exposed people to something they rarely see on film–the unique perspective of young girls of color.

Through its work directly with young people, GGE has developed a language to speak about sexual harassment and strategies to address gender-based violence in public schools. I had an opportunity to speak with Joanne Smith last week and I asked her how Clutch readers might employ these strategies with the girls in our lives.

Have a conversation. According to Smith, adults are often eager to deliver important messages, but not to listen. As an ally, it’s important to understand a girl’s point of view. Start by asking whether she knows about street harassment. You may use an article, a real-life incident or maybe the book, Hey Shorty, as an entry point.

Remember that younger generations are experiencing life differently. Today’s girls are inundated with aggressive sexuality through media, music, smart phones and social media. Their tolerance of certain behaviors may be different from that of Gen X or Baby Boomer parents. Smith admits that coping with this difference in experience can be difficult. What happens, for instance, when your daughter tells you dismissively, “He just touched my butt. It’s no big deal.”

Smith says, take the opportunity for a conversation. How often does he touch your butt? Is that just what you do? Do you touch his butt back? “You’re not trying to indict her. You’re trying to build trust so that you can help her to make decisions.”

A girl doesn’t enter the ninth grade and suddenly decide that unsolicited touching is okay. Smith says, “Since she was 11, she has probably been dealing with street harassment and some form of sexual harassment or gender oppression. She’s had to make hundreds of decisions throughout the day without deferring to mom.”

Smith says a high percentage of school-age children do not identify a parent as someone to go to should they face problems like sexual harassment. They know their parents love them, but they are afraid of being shamed or blamed.

Girls need to be able to express themselves, in their language, and be empowered and supported.

Become an ally to a young woman. Young women and girls need to know that older women in their lives are allies. They need to hear our stories–that we have experienced many of the same things (though our experiences don’t necessarily frame or explain their experiences).

But Smith also reminds that girls need the company of young women their own age who are addressing issues like street harassment. “When I was 15, being exposed to other 15-year-olds have critical conversations was invaluable, as opposed to adults having those conversations. Girls need to know about the amazing organizations that they can be a part of and that there are allies who can support them in whatever it is that they’re going through.”

Tell her: It’s not your fault. Most importantly–girls need to understand that it is not their fault when they are being objectified and that they don’t have to tolerate it. They have a right to tell a boy that his attention is unwanted. If he doesn’t stop, that’s harassment. In school, under Title IX, all students have a right to report (or not report) harassment and receive relief.

Girls who witness harassment can help other girls by supporting them, talking to them and walking with them. They need to understand that harassment is not a right of passage for men and, though it may seem like a social norm, it’s not okay.

Don’t just talk to girls. Boys can be bigger allies than we think, says Smith. Much of street harassment involves displays of “manhood” that boys and young men perform for each other as twisted rights of passage. GGE programs encourage dialogue about gender roles and experiences.

Smith recalls a GGE Gender Respect Workshop in a middle school. The facilitator asked a handsome young man how he felt each morning coming to school. “I’m excited! I’m going see all my boys and hang out and play basketball.” She asked a classmate–a girl–the same question. Her answer was quite different. “I feel insecure,” she said. “Eyes are turned on me. I wonder what these boys are going to say to me now.”

The boy was astounded at the idea that girls might fear him. He saw his behavior and that of his friends as harmless flirting. “I would never do anything to you.” Hearing his classmate’s perspective illuminated what the young man could do to help change the dynamic on the schoolyard.

Talk to your kids at least once a day. And tell them to make good decisions. “It resonates,” Smith says.

Donate and learn more about Girls for Gender Equity at www.ggenyc.org. You can also purchase copies of the Hey Shorty book and DVD. Follow GGE on Facebook and Twitter.