photo by Alex Lear

DO RIGHT WOMEN

Black Women, Eroticism and Classic Blues

1.

|

I'm going to show you women, honey,

how to cock it on the wall

Now you can snatch it, you can break it, you can

hang it on the wall

Throw it out the window, see if you

can catch it 'fore it fall

—Louise Johnson

|

I fantasize spanking you. What sexual fantasies do you have?" an ex-lover intoned into the phone receiver.

As she spoke I remembered a time when we were in one of those classical numeral positions and at a peak moment I felt the sharp smack of her bare palm on my bare butt--not in pain nor anger, but surprisingly, for me, I remember a tingle of pleasure, the pleasure in knowing that I had been the catalyst for her, a person of supreme sexual control, going over the edge.

After I hung up, I admitted to myself that like many males my main fantasy was to be sexually attractive to and sexually satisfying for thousands of women. I "fantasize" sexually engaging at least a quarter of the women I see, ninety percent of whom I don't know beyond eyeing them for a moment as I drive down some street, spot them in a store, in an office building, in line paying a bill, or walking ahead of me out of a movie.

I remember in one of my writing workshops in the fall of 1995 I shocked a room of young men by declaring that sexual expression among male homosexuals represented the fullest flowering of male sexuality. Some reacted predictably from a position of virulent homophobia and others were just genuinely skeptical.

I explained that if he could, assuming that there were no restraints and that it was consensual sex between adults, then the average American male would engage in promiscuous sex every time they felt aroused--which undoubtedly would be often. A major brake on our promiscuousness is the unwillingness of women to cooperate with male socio-biological urges.

I asked one of the more skeptical homophobes in my workshop, "haven't you seen a woman today you wished that you could get down with, a woman whom you didn't know personally?" He smiled and answered "yeah, on my way to class just now." After the laughter died down, I told him that this is indeed what often happens with gay sex precisely because there is no restraint other than desire and safety.

American male sexuality is, among other characteristics, a celebration of the moment. Our fantasy is immediate sexual gratification with whomever catches our fancy. Most of the time we deny, transfer, repress, or misrepresent these fantasies. However, in popular music we forcefully articulate the male desire to wantonly enjoy coition with women.

Thus, these 90's rap and r&b ("rhythm and booty") records about rampant sex with a bevy of willing cuties is not just adolescent, post-puberty fantasizing but rather is an accurate projection of ethically unchecked and socially unshaped male sexuality--a sexuality which projects the male as the dominating, aggressive subject and the female as the pliant (if not willing) object of consumption.

Here is a significant cultural crossroads. I hold no truck in prudish and/or puritanical views of sex; while I abhor pornography (the commidifying of sex and the reifying of a person or gender into a sexual object), I am opposed to censorship. The status quo would have the whole debate about the representation of sexuality boil down to either reticence or profligacy. The truth is those extremes are not different roads. They are simply the up and down side of the status quo view which either come from or lead to the objectifying of sexual relations. Objectifying sexual relations is a completely different road from the frank articulation of eroticism.

Within the American cultural context, this difference is nowhere as clearly presented as in the early, 1920's woman-centered music known as "Classic Blues."

2.

|

You never get nothing by being an angel child,

You better change your ways and get real wild,

I want to tell you something and I wouldn't tell you no lie,

Wild women are the only kind that really get by,

'Cause wild women don't worry, wild women don't have the blues.

—Ida Cox

|

Known today as "Classic Blues" divas, these women married big city dreams with post-plantation realties and, by using the vernacular and folk-wisdom of the people, gave voice to our people's hopes and sorrows and specifically spoke to the yearnings and aspirations of Black women recently migrated to the city from the country. While many women took up domestic and factory work, the entertainment industry also was a major employer of Black women. In Black Pearls author Daphne Harrison sets the stage:

|

Young black women with talent began to emerge from the churches, schools, and clubs where they had sung, recited, danced, or played, and ventured into the more lucrative aspects of the entertainment world, in response to the growing demand for talent in the theaters and traveling shows. The financial rewards often out-weighed community censure, for by 1910-1911 they could usually earn upwards of fifty dollars a week, while their domestic counterparts earned only eight to ten dollars. Many aspiring young women went to the cities as domestics in hope of ultimately getting on stage. While the domestics' social contacts were severely limited, mainly to the white employers and to their own families, the stage performer had an admiring audience in addition to family and friends. (Harrison, page 21)

|

The Classic Blues divas who emerged from this social milieu were more than entertainers, they were role models, advice givers, and a social force for cultural transformation.

|

Ma Rainey is considered the mother of the Classic Blues. "She jes' catch hold of us, somekinaway." scripts poet Sterling Brown in giving a right on the money description of the cathartic power of Ma Rainey's majestic embrace which wrapped up her audience and reared them into the discovery of self-actulization's rarefied air. "Git way inside us, / Keep us strong" (Brown, pages 62 - 63).

Birthed by these women, we became our selves as a people and as sexually active individuals. Twenties Classic Blues was the first and only time that independent African-American women were at the creative center of Black musical culture. Neither before nor since have women been as economically or psychologically "liberated."

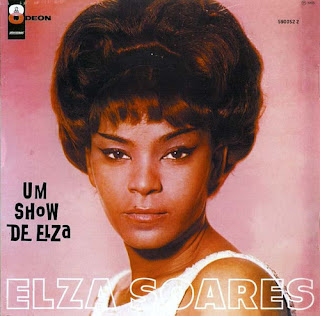

Ma Rainey & Her Georgia Band

|

|

In a country dominated by patriarchal values, mores and male leadership (should we more accurately say "overseership"?), Classic Blues is remarkable. Remember that although slavery ended with the Civil War in 1866 and the passage of the 15th amendment to the Constitution, suffrage for women was not enacted until 1920 with the 19th amendment. The suffrage movement, which had been dominated by White women, was also intimately aligned with the temperance movement, a movement which demonized jazz and blues.

Black women were a major organizing and stabilizing force in and on behalf of the Black community between post-Reconstruction and the Twenties. Historian Darlene Hine notes:

|

The second period began in the 1890s and ended around 1930 and is best referred to as the First Era of the Black Woman...black women were among the most active and determined agents for community building and race survival. Their style was concentrated on internal developments within the black community and is reflected in the massive mobilization that led to the formation of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs that boasted a membership of over 50,000 by 1914. ... Black women perfected a "politics of respectability," a "culture of dissemblance," and a cult of secrecy and silence. (Hine, page 118-119)

|

But a curious dynamic has always animated Black America--while those who hoped to assimilate, to be accepted and/or to achieve "wealth and happiness" strove for and advocated a "politics of respectability" the folk masses sang a blues song a la Langston Hughes' mule who was black and didn't give a damn, if you wanted him, you had to take him just as he am. In other words, the blues aesthetic upsets the respectability applecart. And at the core of the blues aesthetic is a celebration of the erotic.

I contend that this is a major cultural battle. Eroticism is the motor that drives Black culture (or, more precisely, drives those aspects of our culture which are not assimilative in representation). Whereas, polite society was too nice to be nasty, blues people felt if it wasn't nasty, then how could it be nice.

As James Cone notes in his perceptive and important book The Spirituals and the Blues:

It has been the vivid description of sex that caused many church people to reject the blues as vulgar or dirty. The Christian tradition has always been ambiguous about sexual intercourse, holding it to be divinely ordained yet the paradigm of rebellious passion. Perhaps this accounts for the absence of sex in the black spirituals and other black church music. ... In the blues there is an open acceptance of sexual love, and it is described in most vivid terms... (Cone, page 117)

Many of us are totally confused about eroticism. Most of us don't appreciate the frank eroticism of nearly all African-heritage cultures which have not been twisted by outside domination (e.g. Christianity and Islam). Commenting on "Songs Of Ritual License From Midwestern Nigeria" African Art Historian Jean Borgtatti notes:

The songs themselves represent an occasion of ritualized verbal license in which men and women ridicule each other's genitalia and sexual habits. Normally such ridicule would be an anti-social act in the extreme... In the ritual context, however, the songs provide recognition, acceptance, and release of that tension which exists between the sexes in all cultures, and so neutralize this potential threat to community stability. (Borgatti, page 60)

The songs in question range from explicit and detailed put-downs to this lyric sung by a woman which could be a twenties blues lyric.

|

When I Refuse Him

When I refuse him, the man is filled with sorrow

When I refuse him, the man is filled with sorrow

When my "thing" is bright and happy like a baby chick, it drives him wild

When my "thing" is bright and happy like a baby chick, it drives him wild

|

My argument is that socially expressed eroticism is part and parcel of our heritage. In the American context, this eroticism is totally absent in the "lyrics" of the spirituals (albeit not totally suppressed in the rituals of black church liturgy). On the other hand, Black eroticism is best expressed and preserved in the blues (beginning in the early 1920s) and in its modern musical offshoots.

Erotic representation is another major point of divergence. Euro-centric representations of eroticism have been predominately visual and textual whereas African-heritage representations have been mainly aural (music) and oral (boasts, toasts, dozens, etc.). The eye sees but does not feel. Mainly the brain responds to and interprets visual stimuli whereas the body as a whole responds to sound.

Moreover, textual erotic representation invites and encourages private and individual activity. E.g. you are probably alone reading this--if not alone in fact certainly alone in effect as there may be others present where you are reading but they are not reading over your shoulder or sitting beside you reading with you.

Moreover, you most certainly are not reading this aloud for general consumption. If you do read it aloud it is probably a one-to-one private act.

Aural and oral erotic representation, on the other hand, require a participating audience, become a ritual of arousal. Music, in particular, is not only social in focus, music also privileges communal eroticism. Thus, whereas text encourages individualism and self-evaluations of deviance, shame and guilt; musical eroticism encourages coupling, group identification and self-evaluations of shared erotic values, sexual self worth and pleasure.

Finally, within the African-American context, sound is used as language to communicate what English words cannot. The African American folk saying, "when you moan the devil don't know what you talking about" contains an ironic edge that goes beyond spiritual commentaries on good and evil. The White oppressor/slave master, i.e. "the devil," does not understand the meaning of moaning partly because of intentional deception on the part of the moaners but also because English lexicon is limited.

|

Moans, wails, cries, hums and other vocal devices communicate feelings, moods, desires and are the core of blues expression. This is why the blues is more powerful than the lyrics of the songs, why blues lyrics do not translate well to the cold page (when the sound of the words is not manifested much of the true meaning of the words is lost), and why blues cannot be accurately analyzed purely from an intellectual standpoint. Moreover, erotic desires, frustrations and fulfillments--the most frequent emotions articulated in the blues--are some of the strongest emotions routinely manifested by human beings.

In the 1920's mainstream America was nowhere near ready to acknowledge and celebrate eroticism. Thus, as far as most Americans were concerned, a frank and explicit expression of eroticism was shameful

|

|

. This social "shame" became the singular trademark of the blues. Moreover, the identification of sexual explicitness with the blues was so thorough that sexually explicit language became known as "blue" as in "cussin' up a blue streak" or the kind of "blue material" which was often "banned in Boston."

Within the context of American Puritanism and Christian anti-eroticism, it is important to note that "blue" erotic music was first brought to national prominence not by men but rather by women. This privileging of feminine sexuality was an unplanned result of the newly developed recording industry's quest for profits. When "Okeh Records sold seventy-five thousand copies of 'Crazy Blues' in the first month and surpassed the one million mark during its first year in the stores" (Barlow, page 128) the hunt was on.

Recording and selling "race records" (i.e. blues) was like a second California gold rush. There was no aesthetic nor philosophical interest in the blues. This was strictly business. Moreover, during the first years of the race record craze, because race records were sold almost exclusively to a Black audience there was less censorship and interference than there otherwise might have been. Black tastes and cultural values drove the market during the twenties. There were both positive and negative results to this commercialization.

On the positive side of the ledger, the mechanical reproduction of millions of blues disks made the music far more accessible to the public in general, and black people in particular. Blues entered an era of unprecedented growth and vitality, surfacing as a national phenomenon by the 1920s. As a result, a new generation of African-American musicians were able to learn from the commercial recordings, to expand their mastery over the various idioms and enhance their instrumental and vocal techniques. The local and regional African-American folk traditions that spawned blues were, in turn, infused with new songs, rhythms, and styles. Thus, the record business was an important catalyst in the development of blues that also facilitated their entrance into the mainstream of popular American music.

On the other hand, the transformation of living musical traditions into commodities to be sold in a capitalist marketplace was bound to have its drawbacks. For one thing, the profits garnered from the sale of blues records invariably went into the coffers of the white businessmen who owned or managed the record companies. The black musicians and vocalists who created the music in the recording studios received a pittance. Furthermore, the major record companies went to great lengths to get the blues to conform to their Tin Pan Alley standards, and they often expected black recording artists to conform to racist stereotypes inherited from blackface minstrelsy. The industry also like to record white performers' "cover" versions of popular blues to entice the white public to buy the records and to "upgrade" the music. Upgrading was synonymous with commercializing; it attempted to bring African-American music more into line with European musical conventions, while superimposing on it a veneer of middle-class Anglo-American respectability. These various practices deprived a significant percentage of recorded blues numbers of their African characteristics and more radical content. (Barlow, pages 123-124)

|

When the depression hit and Black audiences no longer had significant disposable income to spend on recordings, the acceptable styles of recorded blues changed drastically.

|

The onset of the depression quickly reversed the fortunes of the entire record industry; sales fell from over $100 million in 1927 to $6 million in 1933. Consequently, race record releases were drastically cut back, field recording ventures into the South were discontinued, the labels manufactured fewer and fewer copies of each title, and record prices fell from seventy-five to thirty-five cents a disk. Whereas the average race record on the market sold approximately ten thousand copies in the mid-twenties, it plummeted to two thousand in 1930, and bottomed out at a dismal four hundred in 1932. The smaller labels were gradually forced out of business, while the major record companies with large catalogues that went into debt were purchased by more prosperous media corporations based in radio and film. The record companies with race catalogues that totally succumbed to the economic downturn were Paramount, Okeh, and Gennett. By 1933, the race record industry appeared to be a fatality of the depression. (Barlow, page 133)

|

|

The Classic Blues divas founded and shaped the form of Black music's initial recording success in the twenties. By the thirties women were completely erased as cultural leaders of Black music. While there was certainly an overriding economic imperative to the cutback, there was also a cultural/philosophical imperative to cut out women altogether.

There was no precedent in either White or Black American culture for women as leaders in articulating eroticism. This significant feminizing of eroticism was predicated on an unprecedented albeit short-lived change in the physical and economic social structure of the Black community converging with a period of massive national economic growth and far reaching mass media technological innovations in recordings, radio, and film.

Despite optimal economic and technological incentives, the twenties rise of the newly emergent Classic Blues diva was no cakewalk, not only because of the virulence of class exploitation, racism and sexism but also because of cultural antagonisms.

Regardless of race, there was an open conflict between the blues and social respectability. The self-assertive, female Classic Blues singer was perceived as a threat to both the American status quo as well as to many of the major political forces seeking to enlarge the status quo (i.e. the petty bourgeoise-oriented talented tenth).

|

|

Moreover, unlike many post-Motown, popular female singers who are produced, directed and packaged by males, Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, Ida Cox, Alberta Hunter, Sippie Wallace, and the incomparable "Empress" of the blues, Bessie Smith, were more than simple fronts for turn-of-the-century blues Svengalies. Yes, men such as Perry Bradford, Clarence Williams, and Thomas Dorsey were major composers, arrangers, accompanists and producers for many of the Classic Blues divas; and yes, these women often were surrounded and beset by men who attempted to physically, financially and psychologically abuse them, nevertheless the Classic Blues divas were neither pushovers nor tearful passive victims.

Emerging from southern backgrounds rich in religious and folk music traditions, they were able to capture in song the sensibilities of black women--North and South--who struggled daily for physical, psychological, and spiritual balance. They did this by calling forth the demons that plagued women and exorcising them in public. Alienation, sex and sexuality, tortured love, loneliness, hard times, marginality, were addressed with an openness that had not previously existed.

The blues women accomplished this with their unique flair for dramatizing their texts and performances. They introduced and refined vocal strategies that gave the lyrics added power. Some of these were instrumentality, voices growling and sliding like trombones, or wailing and piercing like clarinets; unexpected word stress; vocal breaks in antiphony with the accompaniment; syncopated phrasing; unlimited improvisation on repetitious refrains or phrases. These innovations, in tandem with the talented instrumentalists who accompanied the blues women, advanced the development of vocal and instrumental jazz.

Of equal significance, because they were such prominent public figures, the blues women presented alternative models of attitude and behavior for black women during the 1920s. They demonstrated that black women could be financially independent, outspoken, and physically attractive. They dressed to emphasize their symbolic importance to their audiences. The queens, regal in their satins, laces, sequins and beads, and feather boas trailing from their bronze or peaches-and-cream shoulders, wore tiaras that sparkled in the lights. The queens held court in dusty little tents, in plush city cabarets, in crowded theaters, in dance halls, and wherever else their loyal subjects would flock to pay homage. They rode in fine limousines, in special railroad cars, and in whatever was available, to carry them from country to town to city and back, singing as they went. The queens filled the hearts and souls of their subjects with joy and laughter and renewed their spirits with the love and hope that came from a deep well of faith and will to endure. (Harrison, pages 221-222)

|

Never since have women performed major leadership roles in the music industry, especially not African-American women. The entertainment industry intentionally curtailed the trend of highly vocal, independent women.

|

Most of the Classic Blues divas, it must be noted, were not svelte sex symbols comparable in either features or figure to White women. The blues shouter was generally a robust, brown or dark-skinned, African-featured women who thought of and carried herself as the equal of any man. America fears the drum and psychologically fears the bearer of the first drum, i.e. the feminine heartbeat that we hear in the womb.

Bessie Smith and her peers, were sexually assertive "wild" women, well endowed with the necessary physical and psychological prowess to take care of themselves.

Actively bisexual, Bessie Smith belied the common "asexual" labeling of stout women, such as is suggested by Nikki Giovanni in "Woman Poem":

|

|

|

it's a sex object if you're pretty

and no love

or love and no sex if you're fat

(Giovanni, page 55)

|

"No sex" was not the reality of the Classic Blues divas. Yes, many of them were then and would now be considered "fat" but they were far from celibate (by either choice or circumstance). Or, as the sarcastic blues lyric notes:

|

I'm a big fat mama, got meat shakin' on my bones

A big fat mama, with plenty meat shakin' on my bones

Every time I shake my stuff, some skinny gal loses her home.

|

In recent years the best description of the liberating function Blues divas served for the Black community is contained in Alice Walker's powerful novel, The Color Purple. Walker's memorable and mythic character Shug Avery is an active bisexual blues singer a la Bessie Smith. Shug instructs the heroine Celie in the recognition and celebration of herself as a sexual being:

Why Miss Celie, [Shug] say, you still a virgin.

What? I ast.

Listen, she say, right down there in your pussy is a little button that gits real hot when you do you know what with somebody. It git hotter and hotter and then it melt. That the good part. But other parts good too, she say. Lot of sucking go on, here and there, she say. Lot of finger and tongue work. (Walker, page 81)

|

Shug then instructs Celie "Here, take this mirror and go look at yourself down there, I bet you never seen it, have you?" The blues becomes a means not only of social self-expression but also of sexual self-discovery, especially for women.

In a life often defined by brutality, exploitation and drudgery, the female discovery and celebration of self-determined sexual pleasure is important. Thus the blues affirms an essential and explicit reversal. We have been taught that we are ugly, the blues celebrates our beauty and this is especially true for Black women.

I lie back on the bed and haul up my dress. Yank down my bloomers. Stick the looking glass tween my legs. Ugh. All that hair. Then my pussy lips be black. Then inside look like a wet rose.

It a lot prettier than you thought, ain't it. she say from the door.

It mine, I say. Where the button?

Right up near the top, she say. The part that stick out a little.

I look at her and touch it with my finger. A little shiver go through me. Nothing much. But just enough to tell me this the right button to mash. (Walker, page 82)

|

The major characteristic of the Classic Blues is that the vast majority of the songs were sexually oriented and nearly all of the singers were women. In his major study of Black music, LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) notes:

|

The great classic blues singers were women... Howard W. Odum and Guy B. Johnson note from a list of predominately classic blues titles, taken from the record catalogues of three "race" companies. "The majority of these formal blues are sung from the point of view of woman... upwards of seventy-five per cent of the songs are written from the woman's point of view. Among the blues singers who have gained a more or less national recognition there is scarcely a man's name to be found." (Jones, page 91)

|

Jones goes on to answer the obvious question of why women dominated in this area:

|

Minstrelsy and vaudeville not only provided employment for a great many women blues singers but helped to develop the concept of the professional Negro female entertainer. Also, the reverence in which most of white society was held by Negroes gave to those Negro entertainers an enormous amount of prestige. Their success was also boosted at the beginning of this century by the emergence of many white women as entertainers and in the twenties, by the great swell of distaff protest regarding women's suffage. All these factors came together to make the entertainment field a glamorous one for Negro women, providing an independence and importance not available in other areas open to them--the church, domestic work, or prostitution. (Jones, page 93)

|

Ann Douglas, in her important book Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s, Terrible Honesty identifies the twenties as a period of (quoting from the dustjacket) "historical transformation: blacks and whites, men and women together created a new American culture, fusing high art and low, espousing the new mass media, repudiating the euphemisms of outdated gentility in favor of a boldly masculinized outspokenness, bringing the African-American folk and popular art heritage briefly but irrevocably into the mainstream." Douglas believes the birth of modernism required the death of the white matriarch.

|

"The two movements, cultural emancipation of America from foreign influences and celebration of its black-and-white heritage, had for a brief but crucial moment a common opponent and a common agenda: the demolition of that block to modernity, or so she seemed, the powerful white middleclass matriarch of the recent Victorian past. My black protagonists were not matrophobic to the same degree as my white ones were, but the New Negro, too, had something to gain from the demise of the Victorian matriarch." (Douglas, page 6)

|

Such anti-matriarch sentiments directly clashed with the reality of female-led Classic Blues.

We are forced to ask the question: does the freedom of the Black man require the destruction of the Black woman? To the degree that the Black woman is a matriarch, a self-possessed and self-directed person, to that same degree there will inevitably be a conflict with the standards of modern America which are misogynist in general and anti-matriarchal in particular.

|

Thanks to the revolt against the matriarch, Christian beliefs and middleclass values would never again be a prerequisite for elite artistic success in America. Nor would plumpness ever again be a broadly sanctioned type of female beauty; the 1920s put the body type of the stout and full-figured matron decisively out of fashion. Once the matriarch and her notions of middle-class piety, racial superiority, and sexual repression were discredited, modern America, led by New York, was free to promote, not an egalitarian society, but something like an egalitarian popular and mass culture aggressively appropriating forms and ideas across race, class, and gender lines. (Douglas, page 8)

|

Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, et al may seem to contradict Douglas' thesis but actually the disappearance of big, Black women from leadership in entertainment is proof that Douglas was correct in her assessment of modern America.

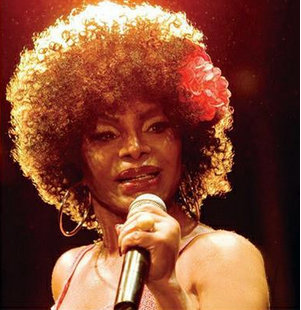

Bessie Smith

|

Among Black people, the Black matriarch continued to reign in the arenas of church, education and community service. However, to the degree that Black people adopt modern American ways to that same degree our culture inevitably becomes "masculinized" and "anti-matriachal." This is inevitable because, as Douglas' book demonstrates in great detail, American modernism is based on the refutation of the woman as culture bearer. Yet culture bearer is precisely the role that the Black woman fulfills.

"The blues woman is the priestess or prophet of the people. She verbalizes the emotion for herself and the audience, articulating the stresses and strains of human relationships" (Cone, page 107). Theologian James Cone, a Christian man, had sense enough to sustain the potency of blues priestesses, a potency which is overtly sexual but which also made strong social, political and economic statements (e.g. "T.B. Blues" by Ida Cox decrying poor health conditions and "Poor Man Blues" by Bessie Smith condemning class exploitation).

|

3.

| |

|

There's a new game, that can't be beat,

You move most everything 'cept your feet,

Called 'Whip it to a jelly, stir it in a bowl',

You just whip it to a jelly, if you like good jelly roll

I wear my skirt up to my knees

And whip that jelly with who I please.

Oh, whip it to a jelly, mmmmmm, mmmm

Mmmmm, mmmm, mmmmm, mmmm

--Clara Smith

|

|

In western culture the celebration of dignity and eroticism does not and can not take place simultaneously. From Freud's theories of sexuality which focus for the most part on penile power to the church which goes so far as to debase the body as a product of original sin, there is no room for the celebration of eroticism, and certainly no conception whatsoever of the female as an active purveyor of erotic power. To me, the blues is clearly an alternative to Freud and Jesus with respect to coming to terms with our bodies.

James Cone correctly analyzes this alternative.

Theologically, the blues reject the Greek distinction between the soul and the body, the physical and the spiritual. They tell us that there is no wholeness without sex, no authentic love without the feel and touch of the physical body. The blues affirm the authenticity of sex as the bodily expression of black soul.

White people obviously cannot understand the love that black people have for each other. People who enslave humanity cannot understand the meaning of human freedom; freedom comes only to those who struggle for it in the context of the community of the enslaved. People who destroy physical bodies with guns, whips, and napalm cannot know the power of physical love. Only those who have been hurt can appreciate the warmth of love that proceeds when persons touch, feel, and embrace each other. The blues are openness to feeling and the emotions of physical love. (Cone, pages 117-118)

|

Moreover, the fact that Freud's theories find their first popular American currency in the 1920s at the same time as Black women's articulation of the Classic Blues suggests an open contest between widely divergent viewpoints. The Classic Blues offered an unashamed and assertive alternative to both the traditional puritanical views of sexuality as well as alternative to the new Freudian psychological views of sexuality. Bessie Smith and company were battling Jesus on the right and Freud on the left.

The puritans with their scarlet letters projected the virgin/whore (Mary mother vs. Mary Madaglene) dualism. For the most part, Freud either ignored the psychology of women, thought they were unfathomable, or else projected onto them the infamous "penis envy."

The period between the Civil War and World War II is the birth of American modernism. It is also the period when the bustle (an artificial attempt to mimic the physique of Black women) was a fashion standard. While it is not within the purview of this essay to address the question of how is it that Black buttocks become a standard of femininity for white society, it is important to at least mention this, so that we can contextualize the battle of worldviews.

Freud proposed the "id" as the controlling element of the civilized individual. The purpose of Black music was precisely to surmount the "id." The individual looses control, is possessed. This trance state is a sought for and enjoyed experience. Rather than be in control we desire to be mounted, i.e. to merge with and be controlled by a greater force outside ourselves. Blues culture validated ritual and merger of the micro-individual into the social and spiritual macro-environment. In this way blues may be understood as an alternative conception of human existence.

In a major theoretical opus on the blues, Blues and the Poetic Spirit, author Paul Garon argues

To those who suggest that the blues singers are 'preoccupied' with sexuality, let us point out that all humanity is preoccupied with sexuality, albeit most often in a repressive way; the blues singers, by establishing their art on a relatively nonrepressive level, strip the 'civilised' disguise from humanity's preoccupation, thus allowing the content to stand as it really is: eroticism as the source of happiness.

The blues, as it reflects human desire, projects the imaginative possibilities of true erotic existence. Hinted at are new realities of non-repressive life, dimly grasped in our current state of alienation and repression, but nonetheless implicit in the character of sexuality as it is treated in the blues. Desire defeats the existing morality--poetry comes into being. (Garon, pages 66-67)

|

Musicologist/theologist Jon Michael Spencer takes Garon's argument deeper when he comments in his book Blues and Evil:

|

Garon was seemingly drawing on the thought of the late French philosopher Michel Foucault, who said in his history of sexuality that if sex is repressed and condemned to prohibition then the person who holds forth in such language, with seeming intentionality, moves, to a certain degree, beyond the reach of power and upsets established law. Sex also might have been a means for "blues people" to feel potent in an oppressive society that made them feel socially and economically impotent, especially since sexuality inside the black community was one area that was free from the restraints of "the law" and the lynch mob.

|

In essence, the Classic Blues as articulated by Black women was not only a conscious articulation of the social self and validation of the feminine sexual self, the Classic Blues was also a total philosophical alternative to the dominant White society. In this regard two incidents in the life of Bessie Smith serve as archetypal illustration.

|

The first is Bessie Smith confrontation with the Ku Klux Klan and the second is Smith's confrontation with Carl Van Vechten's wife. The Klan is the apotheosis of racist, right wing America. Carl Van Vechten is the personification of liberal America.

In Chris Albertson biography of Bessie Smith he describes Smith's July 1927 confrontation with the Klan that occurred when sheeted Klan members were attempting to "collapse Bessie's tent; they had already pulled up several stakes." When a band member told Smith what was going on the following ensued.

|

|

"Some shit!" she said, and ordered the prop boys to follow her around the tent. When they were within a few feet of the Klansmen, the boys withdrew to a safe distance. Bessie had not told them why she wanted them, and one look at the white hoods was all the discouragement they needed.

Not Bessie. She ran toward the intruders, stopped within ten feet of them, placed one hand on her hip, and shook a clenched fist at the Klansmen. "What the fuck you think you're doin'?" she shouted above the sound of the band. "I'll get the whole damn tent out here if I have to. You just pick up them sheets and run!"

The Klansmen, apparently too surprised to move, just stood there and gawked. Bessie hurled obscenities at them until they finally turned and disappeared quietly into the darkness.

"I ain't never heard of such shit," said Bessie, and walked back to where her prop boys stood. "And as for you, you ain't nothin' but a bunch of sissies."

|

Then she went back into the tent as if she had just settled a routine matter. (Albertson, pages 132-133)

Bessie Smith was not an apolitical entertainer. She was a fighter whose sexual persona was aligned with a strong sense of political self-determination. This "strength" of character is another reason that singers such as Bessie Smith were widely celebrated in the Black community. Furthermore, Smith not only was not intimidated by the right, she was equally unimpressed with the liberal sector of American society, as the incident at the Van Vechten household demonstrates. Along with his wife Fania Marinoff, a former Russian ballerina, Carl Van Vechten ("Carlo") was the major patron of the Harlem Renaissance. Albertson describes "Carlo" as an individual who "typified the upper-class white liberal of his day" (Albertson, page 138).

|

Van Vechten loved the ghetto's pulsating music and strapping young men, and he maintained a Harlem apartment--decorated in black with silver stars on the ceiling and seductive red lights--for his notorious nocturnal gatherings.

His favorite black singers were Ethel waters, Clara Smith, and Bessie. (Albertson, page 139)

|

Van Vechten persistently sought Bessie Smith as a salon guest. She resisted but finally relented after continuous entreaties from one of her band members, composer and accompanist Porter Grainger, who desperately wished to be included among Van Vechten's "in crowd." Smith finally agreed to make a quick between sets appearance. Bessie exquisitely sang "six or seven numbers" taking a strong drink between each number. And then it was time to rush back to the Lafayette Theatre to do their second show of the night.

All went well until an effusive woman stopped them a few steps from the front door. It was Bessie's hostess, Fania Marinoff Van Vechten.

"Miss Smith," she said, throwing her arms around Bessie's massive neck and pulling it forward, "you're not leaving without kissing me goodbye."

That was all Bessie needed.

"Get the fuck away from me," she roared, thrusting her arms forward and knocking the woman to the floor, "I ain't never heard of such shit!"

In the silence that followed, Bessie stood in the middle of the foyer, ready to take on the whole crowd.

"It's all right, Miss Smith," [Carl Van Vechten] said softly, trailing behind the threesome in the hall. "You were magnificent tonight." (Albertson, page 143)

|

What does any of this have to do with eroticism? These are examples of Black womanhood in action accepting no shit from either friend or foe. Blues divas such as Bessie Smith were neither afraid of nor envious of Whites. This social self assuredness is intimately entwined with their sense of sexual self assuredness. As Harrison perceptively points out, the Classic Blues divas "introduced a new, different model of black women--more assertive, sexy, sexually aware, independent, realistic, complex, alive." (Harrison, page 111).

These blues singers were eventually replaced in the entertainment sphere by mulatto entertainers and chocolate exotics, Josephine Baker preeminent among them. Significantly, the replacements for Blues divas were popular song stylists who aimed their art at White men rather than at the Black community in general and Black women specifically. The replacements for the big, Black, Classic Blues diva marked the consolidation of the modern entertainment industry's sexual commodification, commercializing and exoticizing of Black female sexuality.

| Although entertainers from Josephine Baker, to Eartha Kitt, to Dianna Ross, to Tina Turner all started off as Black women they ended up projected as sex symbols adored by a predominately White male audience. In that context, sexuality becomes, at best, symbolic prostitution. The Black woman as exotic-erotic temptress of suppressed White male libidos is the complete antithesis of Classic Blues singer. The Classic Blues singer did not sell her sexuality to her oppressor. This question of cultural and personal integrity marks the difference between the sexual commodification inherent in today's entertainment world (especially when one realizes that the major record buying public for many hardcore rap artists is composed of White teenagers) and the sexual affirmation essential to Classic Blues. |

Another important point is that Classic Blues celebrated Black eroticism based in a literal "Black, Brown or Beige" body rather than in a "white looking" mulatto body.

When we look at pictures of Classic Blues divas, we see our mothers, aunts, and older lady friends. Indeed, by all-American beauty standards most of these women would be considered plain (at best), and many would be called "ugly."

For example, Ma Rainey was often crudely and cruelly demeaned. Giles Oakley's book The Devil's Music, A History of the Blues quotes Little Brother Montgomery "Boy, she was the horrible-lookingest thing I ever see!" and Georgia Tom Dorsey "Well, I couldn't say she was a good-looking woman and she was stout. But she was one of the loveliest people I ever worked for or worked with." Oakley opines

|

She was an extraordinary-looking woman, ugly-attractive with a short, stubby body, big-featured face and a vividly painted mouth full of gold teeth; she would be loaded down with diamonds--in her ears, round her neck, in a tiara on her head, on her hands, everywhere. Beads and bangles mingled jingling with the frills on her expensive stage gowns. For a time her trademark was a fabulous necklace of gold coins, from 2.50 dollar coins to heavy 20 dollar 'Eagles' with matching gold earrings.

|

I'm sure the majority of Ma Rainey's female audience did not fail to notice that Ma Rainey resembled them--she looked like they did and they looked like she did. There is no alienation of physical looks between the Classic Blues singer and the majority of her working class Black audience. Physical-appearance alienation of artist from audience is another byproduct of the commodification of Black music.

What started out as a ritual celebration of openly eroticized life was transformed by the entertainment industry into mass-media pornography--the priestess became a prostitute. Albertson's citing of a colorfully written Van Vechten assessment of a Bessie Smith performance clarifies the difference between Bessie Smith performing mainly for Black people and subsequent "Black beauties" (including the famous Cotton Club dancers and singers) performing almost exclusively for Whites. Van Vechten not only points out the literally Black make up of Smith's audience, he also points out how Black women identified with Bessie Smith.

|

Now, inspired partly by the powerfully magnetic personality of this elemental conjure woman with her plangent African voice, quivering with passion and pain, sounding as if it had been developed at the sources of the Nile, the black and blue-black crowd, notable for the absence of mulattoes, burst into hysterical, semi-religious shrieks of sorrow and lamentation. Amens rent the air. Little nervous giggles, like the shattering of Venetian glass, shocked our nerves. When Bessie proclaimed, "It's true I loves you, but I won't take mistreatment any mo," a girl sitting beneath our box called "Dat's right! Say it, sister!" (Albertson, page 107)

|

The implication of such example is psychologically far-reaching and explicitly threatening to male chauvinism, as Harrison explicates:

|

...the silent, suffering woman is replaced by a loud-talking mama, reared-back with one hand on her hip and with the other wagging a pointed finger vigorously as she denounces the two-timing dude. Ntozage Shange, Alice Walker, and Zora Neale Hurston employ this scenario as the pivotal point in a negative relationship between the heroine/protagonists and their abusive men. Going public is their declaration of independence. Blues of this nature communicated to women listeners that they were members of a sisterhood that did not have to tolerate mistreatment. (Harrison, page 89)

|

That these women--big, black, tough, non-virginal, sexually aggressive--were superstars of their era is testimony to the strength of a totally oppositional standard of human value. Their value was not one of physical appearance but one of spiritual relevance. And make no mistake, at that time there was no shortage of mulatto chorines and canaries--Lena Horne, archetypal amongst such "All-American beauties." Nor was there an absence of White male sex-lust for exotic-erotic mulattoes. The difference was that during the twenties there was an unassimilated Black audience which self-consciously embraced/squeezed the blacker berry, i.e. the Classic Blues diva.

The Classic Blues diva was an extraordinary woman whose relevance to a Black audience has never been approached, not to mention matched. William Barlow's assessment is fundamentally correct.

|

The classic blues women's feminist discourse grappled with the race, class, and sexual injustices they encountered living in urban America. They were outspoken opponents of racial discrimination in all guises, and hence critical of the dominant white social order--even while benefiting from it more than most of their peers. They identified with the struggles of the masses of black people, empathized with the plight of the downtrodden, and sang out for social change. Within the black community, the classic blues women were also critical of the way they were treated by men, challenging the sexual double standard. Concurrently, they reaffirmed and reclaimed their feminine powers--sexual and spiritual--to remake the world in their own image and to their own liking. This included freedom of choice across the social spectrum--from political to sexual resistance, from black nationalism to lesbianism. Like the first-generation rural blues troubadours, the classic blues women were cultural rebels, ahead of the times artistically and in the forefront of resistance to all the various forms of domination they encountered. (Barlow, pages 180-181)

|

At the essential core of the Classic Blues was a throbbing, vital eroticism, an eroticism that manifested itself in the lifestyle and subject matter of the Classic Blues divas. Although we can analyze in hindsight, the ultimate manifestation of blue eroticism is not to be found nor appreciated in intellectualism but in its funky sound which must be experienced to be fully appreciated. Once again, Alice Walker's The Color Purple is exemplar in portraying the importance of the blue erotic sound--an eroticism best articulated by Black women.

|

Shug say to Squeak, I mean, Mary Agnes, You ought to sing in public.

Mary Agnes say, Naw. She think cause she don't sing big and broad like Shug nobody want to hear her. But Shug say she wrong.

What about all them funny voices you hear singing in church? Shug say. What about all them sounds that sound good but they not the sounds you thought folks could make? What bout that? Then she start moaning. Sound like death approaching, angels can't prevent it. It raise the hair on the back of your neck. But it really sound sort of like panthers would sound if they could sing.

I tell you something else, Shug say to Mary Agnes, listening to you sing, folks git to thinking bout a good screw.

Aw, Miss Shug, say Mary Agnes, changing color.

Shug say, What, too shamefaced to put singing and dancing and fucking together? She laugh. That's the reason they call what us sing the devil's music. Devils love to fuck. (Walker, page 120)

|

* * * * *

WORKS CITED

Albertson, Chris. Bessie. Braircliff: Stein and Day Paperback, 1985 (Originally issued 1972)

Barlow, William. Looking Up At Down. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989

Borgatti, Jean. "Songs Of Ritual License From Midwestern Nigeria." In Alcheringa Ethnopoetics (New Series Volume 2, Number 1). Dennis Tedlock and Jerome Rothenberg, editors. Boston: Boston University, 1976

Brown, Sterling A. The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown. Michael S. Harper, editor. Chicago: TriQuarterly Books, 1989

Cone, James H. The Spirituals and the Blues. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1972

Douglas, Ann. Terrible Honesty. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995

Garon, Paul. Blues & The Poetic Spirit. New York: Da Capo Press, 1975

Giovanni, Nikki. The Selected Poems of Nikki Giovanni. New York: William Morrow, 1996

Harrison, Daphne Duval. Black Pearls, Blues Queens of the 1920s. Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990

Hine, Darlene Clark. Speak Truth To Power. Brooklyn: Carlson Publishing, Inc., 1996

Jones, LeRoi. Blues People. New York: Morrow Quill Paperbacks, 1963

Oakley, Giles. The Devil's Music, A History of the Blues. New York: Harvest/HBJ book, 1976

Spencer, Jon Michael. Blues and Evil. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993

Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. New York: Pocket Books/Washington Square Press, 1982