These two Xochipala-style figurines at the Metropolitan Museum of Art date from the 13th-10th century B.C. Some historians believe this culture was a predecessor to the Olmecs.

The myth of Black inferiority has and continues to plague the Americas, resulting in the suppression and denial of the African influence in the Americas prior to Columbus’ trip in 1492. There is overwhelmingly convincing evidence that not only names Africa as the birthplace of modern human beings but also as the birthplace of civilization and of technology far ahead of its time. Though civilizations such as the Olmecs have numerous similarities which seem to connect them to Africa, many scholars, primarily Latino scholars, have unsuccessfully attempted to discredit the theory that Africans came to the Americas before Columbus, which helps explain the striking similarities between Egyptian culture and Mesoamerican culture.

According to Michel N. Laham, M.D., and Richard J. Karam, J.D., in their informative essay, “Did the Pheonicians Discover America?” evidence shows that there were actually two trips made to the Americas long before Colombia. The first of the two trips was taken circa 600 B.C. by the Egyptian Pharoah Necho with the aid of the seafaring Phoenicians. The second trip took place circa 450 B.C. by the Carthaginians. These voyages have for some reason been excluded for the traditional history books.

This, however, comes as no surprise considering the fact that much of the overwhelmingly convincing evidence that ties Native American civilization to Africa is suppressed. Genetic trees were recently produced which prove that the entire human population descends from an African female that the media named “Eve,” and geneticists subsequently found the same for the male they named “Adam.” Since the introduction of the “Adam and Eve” genetic trees, they have also been used to determine, in the first exodus, the routes the early Africans took out of Africa.

The Costa Chica region, near the Gulf of Mexico, is the area in Mexico with the highest population of Mexicans with African roots. This is primarily due to the fact that Veracruz, a city in the area, served as a slave port throughout the early colonial period.

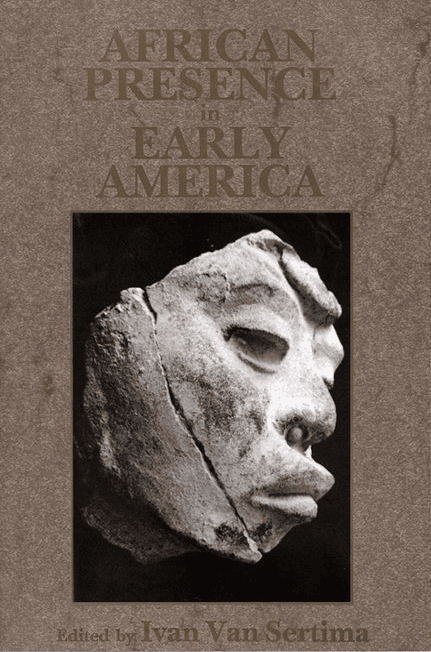

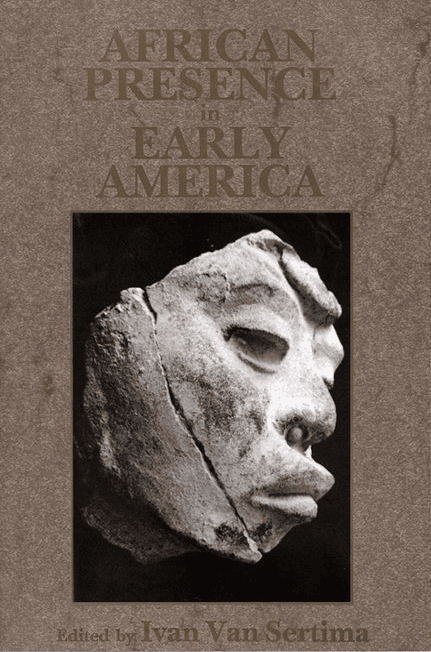

However, there is sufficient evidence to prove that the African presence preceded the colonization of America by the Europeans. Some evidence introduced by Ivan Van Sertima in “Van Sertima’s Address to the Smithsonian,” the first chapter in “African Presence in Early America,” to support this claim would include ancient monuments such as the Olmec heads (statues with African features), pyramids with kings buried inside as they were in Egypt and dark figurines made to look exactly like some of the mummies in early Egypt (with arms crossed over chest, fingers spread and ribs outlined) as well as a sculpture of an Olmec woman from Xochipala in pre-Christain Mexico, approximately 3,000 years old with African headdress and ear pendants.

The Gulf of Mexico, the end-point of the currents that flow from Africa to the Americas, was the coastline upon which Olmec civilization, considered to be the “mother-culture” of America, thrived. Van Sertima reports that in 1964, the International Congress of Americanists argued, “There cannot now be any doubt but that there were visitors from the Old World to the New before 1492.”

To support this claim, in 1858 an enormous stone head was discovered and described as having “Africoid” features. Upon further examination, this head was discovered to have seven braids, signifying African headdress.

This portrayal of an Olmec king, showing his African hairstyle, is from the Tres Zapotes archeological site in Veracruz, a largely Black city on the Gulf of Mexico.

Brian Smith, in his scholarly essay, “African Influence in the Music of Mexico’s Costa Chica Region,” further supports the claim of the suppression of the African influence on Mesoamerican civilization and notes how the European and Indigenous contributions in Native American folk songs are thoroughly celebrated, but the instruments with African influence are not as highly publicized. Among those instruments are the marímbola, the quijada and the tambor de fricción. This serves as just another example of the suppression of the African contribution to Mesoamerican culture and tradition.

Discrimination in Latin America is also widespread and prevalent. John Logan, in his educational research paper, “How Race Counts for Hispanic Americans,” places Hispanic people in three categories: Hispanic Hispanics, Black Hispanics and White Hispanics. He reports that Black Africans are significantly more subject to discrimination, especially in major Latin American cities. He also stated that they live in more densely populated neighborhoods with similar conditions to non-Hispanic Blacks.

According to John Mitchell’s Los Angeles Times article, “Mexico’s Black History Is Often Ignored,” Mexicans are a “mixed race.” “But it’s the mixture of indigenous and European heritage that most Mexicans embrace; the African legacy is overlooked,” he adds. This only further solidifies the theory of discrimination and the myth of Black inferiority in Latin America.

Black inferiority is a notion so prevalent in America that mulattoes – people of mixed Black and white descent – are looked down upon and in Dr. David Pilgrim’s Ferris State University article, “The Tragic Mulatto Myth,” there are many examples of mulattoes, specifically females, portrayed in the media as unhappy and anxious to have a white lover, which would ultimately lead to their downfall. There are also other instances where a mulatto woman who could pass for white would have her secret exposed and commit suicide, other women were painted as seductresses and mulatto men were portrayed by the media as rapists who had both the “greed and ambition” of the white man combined with the “savagery and barbarism” of the Black man. Once again, the myth is Black inferiority is enforced and the Black condition exacerbated by the media.

With such vile conceptions of Africans, the question arises, if African history and Africa’s contributions to society and the world were celebrated, would discrimination and mass incarceration of Blacks be so prevalent? The obvious answer is yes; however, a lot of work still needs to be done in order to correct the wrongs inflicted upon Africans in America and beyond and a lot of effort will be needed to rewrite an accurate representation of the history of mankind.

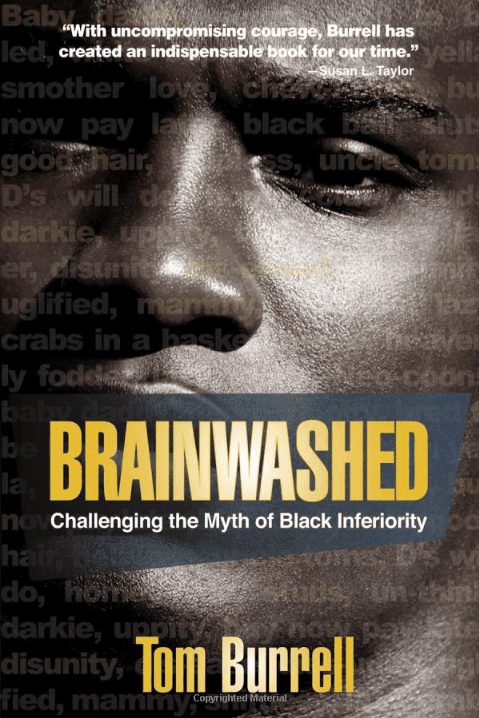

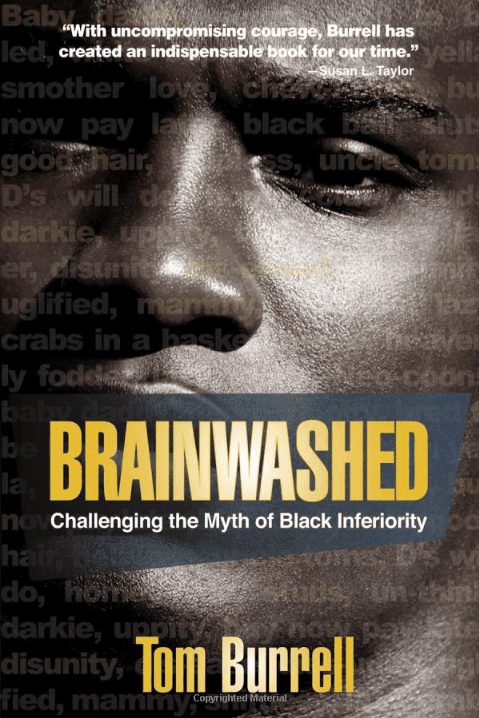

Chicago advertising legend Tom Burrell, in his book, “Brainwashed: Challenging the Myth of Black Inferiority,” argues that the subliminal promotion of White superiority and Black inferiority has been the biggest and most successful marketing campaign in history. Burrell, leading into the first chapter of the book, quotes W.E.B. Du Bois’ statement:

“But in propaganda against the Negro since emancipation in this land, we face one of the most stupendous efforts the world ever saw to discredit human beings, an effort involving universities, history, science, social life and religion.”

With Black inferiority being so widespread and prevalent in the Americas, it comes as no surprise that people would want to disconnect themselves from their African lineage and would rather their history be considered “home-grown” or indigenous. Burrell is quoted in the Dawn Turner Trice’s Chicago Tribune article, “Challenging the Myth of Black Inferiority,” stating, “We have to understand that images, symbols and words can be so powerful and ubiquitous that they affect behavior without us knowing it.” This just goes to show the subconscious effect of propaganda on our society and the way people are perceived and prejudged.

Burrell also writes in his book of the low expectations African Americans, due to propaganda, have of themselves and other African Americans and how even the images of successful Black figures can serve to support these thought patterns. He writes that successful Black figures being put in the spotlight are seen as “exceptions to the rule” and further accentuate the myth of a post-racial society by creating the illusion that anyone can succeed. Burrell calls this the “paradox of progress.” The common misconception of a post-racial society combined with propagandized images of African-Americans serve to subconsciously preserve the myth of Black inferiority and to preserve the subconscious aspect of discrimination and inequality in today’s society.

Wilma A. Dunaway, in her scholarly book, “The African-American Family in Slavery and Emancipation,” argues that there has been a preposterous notion that slavery was a “paternal institution” that “civilized and Christianized” Africans and that they were somehow better off than many free Northern workers due in part to the fact that they were “cared for” by their masters in their non-working hours and old age.

However, much of the research surrounding the institution of slavery in the United States has been conducted by the examination of journals and diaries kept by slave owners and therefore is extremely biased to make the slave owners seem humane and the slaves to seem inferior in order to justify the ridiculous institution of slavery and to downplay the impact that it had and continues to have on people of African descent as well as the shaping of Western society.

DeBray “Fly Benzo” Carpenter has been the target of incessant police harassment and brutality since he began leading protests against the police murder of Kenneth Harding on July 16, 2011. He was recently convicted by a jury that included no Blacks of three misdemeanors – resisting arrest, obstructing a police officer and assault on a police officer – stemming from a brutal assault on him by police in a public plaza in front of a crowd of witnesses. The trial, which lasted several weeks, made schoolwork difficult, but he is maintaining his straight-A grade average. Here he is working on an assignment in the Rosenberg Library at City College. – Photo: Sara Bloomberg, The Guardsman

The ever-present propaganda campaign of white superiority and Black inferiority, since slavery, has succeeded in rewriting history without its African roots and has continued to downplay Africa’s contribution to civilization and to the world as we know it. If Africa were more effectively promoted as the birthplace of civilization and the beginning source of all sophisticated culture, the myth of Black inferiority would be forced out of society because it would then be evident that we are all connected and, ultimately, all African.

Bayview Hunters Point community advocate and straight-A City College student DeBray “Fly Benzo” Carpenter can be reached on Facebook, at Fly Benzo’s Blog, where this story first appeared, or via flybenzo@gmail.com.

For good reasons, most non-profits have way too many diverse audiences, even in their own supporter bases, to ever speak so boldly. I honestly don't know the solution to this other than to get to know audience segments more and target stronger communications at each segment, like politicians are so good at doing, which should be easier with modern CRM software and a little creativity.

For good reasons, most non-profits have way too many diverse audiences, even in their own supporter bases, to ever speak so boldly. I honestly don't know the solution to this other than to get to know audience segments more and target stronger communications at each segment, like politicians are so good at doing, which should be easier with modern CRM software and a little creativity. It's a fact of life in most NGO's there are multiple, often competing priorities, because there's lots of work to be done. Groups like IC and even

It's a fact of life in most NGO's there are multiple, often competing priorities, because there's lots of work to be done. Groups like IC and even

March 14th, 2012 at 12:10 pm

For me, it’s a not a question of how much you need to simplify. It’s a question of how much simplification of such issues is ethical. No, causes don’t typically raise money by making nuanced, complicated statements. On the other hand, some simplification verges on misrepresentation. I mean, why not abandon facts altogether if it gives the message more impact? That seems to be where we’re headed. And when what we’re attempting to raise is not money, but awareness of complicated issues, then I think the game is altogether different.

Like everything else in American culture, good causes are now overmarketed to the point where they may no longer be so good.

++++++

Ethan Zuckerman's musings on Africa, international development

and hacking the media.