Race and Burlesque:

The curious case of

the performer of colour.

Published on February 7, 2013

By Chocolat The Extraordinaire.

It was around 2003 that I started going to Lady Luck Club, an underground nightclub playing vintage rhythm’n’ blues in a dark basement in central London.

Chocolat The Extraordinaire. ©Neil Lewis

It was the first time I’d ever seen burlesque dancers on stage and I was mesmerised; I watched them gyrate and flirt and pose, and I knew for certain that I wanted to do what they were doing and I had every confidence that I could. It was only when I got home and started obsessively looking for more information on how I could become one of those girls that I realised none of them looked like me. In all honesty, the fact that I’d be the only black girl doing it delighted me – I was only eighteen and I was perhaps a bit arrogant; I felt special. I swallowed any moment of intimidation I felt and shimmied on. In fact, I used this as my fuel to succeed.

The only other non-white face I could find already performing burlesque in the UK was the awe-inspiring Fancy Chance, and after a few months of performing I met and became fast friends with a ball of burlesque energy called Marianne Cheesecake. So, out of a scene of about maybe fifty girls working regularly, there were three of us who weren’t white. Over the next few years, two or three more girls of colour started performing, but they were few and far between and I became more and more disillusioned; it saddened me. I kept on waiting for a big racial boom; I kept thinking, ‘any minute now a whole load of black girls are going to flood in.’ But it just didn’t happen.

“How can a scene, that by its very nature is such a radical alternative to mainstream entertainment, be so lacking in diversity?”

Coming from an African background, a big problem for me back then was that I had been too scared to share my career with my family for fear of them not approving of my choices; I was convinced I’d be disowned. As La Cholita noted: ‘I think culturally it is more taboo for minorities. There are negative connotations associated with showing your body and being openly sexual. It’s meant to only happen behind closed doors with your husband’. After a few years, the weight of keeping my massive secret became too much to bear and I decided I’d had enough of burlesque; I stopped performing completely and told myself I wouldn’t miss it. But I was wrong, and when I returned to burlesque in 2012 I expected to see a whole new onslaught of performers who looked more like me. Having been almost a decade since I first twirled a tassel on stage, I was shocked to find only a handful of new performers of colour. How can a scene, that by its very nature is such a radical alternative to mainstream entertainment, be so lacking in diversity?

A Cotton Club woodcut.

What may shock you to discover – because it sure as hell shocked me – is that it wasn’t always this way. Quite the opposite in fact: black, Asian and Hispanic burlesque performers (or ‘shake dancers’ as they were often referred to back then) were commonplace all over the striptease circuit in the 1950′s and sixties, dancing everywhere from The Cotton Club to Minskys, and from Club Harlem to Les Folies Bergere.

“Not only are jobs plentiful for shapely, near-nude dancers who can fit the right moves to bouncy music, but the pay is good, which is the main reason why girls become shake dancers.”

Jet Magazine, 29th October, 1953.

Able to earn triple the wage offered by their civilian jobs, shake dancing was a lucrative career for many women of this time. A top billed shake dancer could expect to earn between $500 and $1000 a week (however, compare this to burlesque star Tempest Storm, who in a burlesque study conducted between 1961-63 was found to be the highest paid stripteaser in the nation, earning a salary of $2000 weekly). Shake dancers gained fame, notoriety and a slew of wealthy admirers, including singers, actors, politicians and even royals:

“Although she’s now singing at Bowman’s Cafe on Sugar Hill, most people remember Madeline (Sajhi) Jackson as a torrid shake dancer at the Cotton Club. An Indian prince once offered her $500,000 to rule his castle as his wife.”

Jet Magazine, 21st April, 1955.

Performers backstage at Forbidden City.

However, this isn’t to say that there wasn’t a disparity between black, Asian, Hispanic and white dancers; although there was more than enough room for all of them to perform, things were far from equal. As burlesque legend Toni Elling told Jo Weldon in an interview, August 2007:

‘A dancer could make some money in the sixties being big busted. I thought about breast implants to make more money … and I realised, ‘You fool, if you do it you’ll still be black!’ They would not pay black girls the same as others. Hispanic and Asian girls were considered white for bookings, everybody but black girls got paid well.’

Nevertheless, the shake dancers of the fifties and sixties were resourceful and focused on earning a decent wage. Many of them were booked to tour the world, made TV appearances and, in later life, made an easy transition into singing at theatres, clubs and casinos.

So where did all the brown girls go? And why weren’t they now flocking to this exciting new burlesque revival in the same numbers as their white counterparts?

The obvious answer, although it’s only one reason among many, is our cultural and historical differences; we are all a product of our environment and of what has come before us. Sydni Deveraux lists one of the factors as ‘the sexualisation of African-Americans throughout history. For instance, I once performed for an entirely black audience and it became clear to me that I was exactly what the entire culture had been fighting against for so long: the hyper-sexualisation of its women.’ It’s a common complaint from women of colour – our two-dimensional portrayal in the mass media as either the maid or the whore. It’s a sad fact that we are so commonly displayed as either overtly sexual or uneducated (or both!) in popular culture, be it in TV advertisements or Hollywood blockbusters, that burlesque doesn’t sit well within our communities and families. Why would we try to reinforce this stereotype by displaying our sexuality so publicly? Wouldn’t we rather prove our worth via more conservative means?

Tropicana Showgirls in Havana, Cuba, 1954. Photo by Foto Marcos

Black, Asian and Hispanic cultures are generally more conservative than Western cultures, and often quite heavily religious. Sexuality isn’t expressed so freely in the public arena; although it’s now become a normality to drive past a poster of an oily topless supermodel selling you mineral water in the UK, you may be hard pressed to find such an erotically charged billboard in West Africa, for example. Personally, I’m a second-generation immigrant and I know how hard my family have worked to push me towards higher education and a stable career – an opportunity that would not have been so easy for them to grab. And so it follows that the thought of throwing these opportunities away in lieu of taking your clothes off on stage in any context can be tantamount to a slap in the face.

‘I think that for a large percentage of immigrants, survival and safety are a priority. Art school, performance, theatre, etc., these are not only privileges and luxuries but literally risky business… My theory about this is that because the parents took the giant risk of coming to this country, they don’t want to see their children take big risks.’

The Shanghai Pearl

How can we expect our communities to support this alternative lifestyle when they often haven’t even heard of the concept of burlesque and are unfamiliar with the image of it? Our faces aren’t usually the faces of the ‘pin-up queen’ or ‘burlesque legend’ in history books or museums. As a performer of colour, it’s a harsh reality that you learn to accept very quickly that you’re not the beauty ideal that the general public think of when they think of burlesque dancers or vintage pin-ups. Sadly, the history of people of colour in pin-up culture and on the burlesque circuit has been largely whitewashed and there wasn’t a massive database such as the internet back then to record all of their contributions. It’s so very important that this isn’t allowed to happen today, because we no longer have an excuse.

Baby Scruggs in Jet Magazine – May, 1952.

‘The faces for pin-up models and burlesque starlets have always been beautiful white women. I think that as long as this image is the mainstream prototype then the men and women of colour will always receive a limited amount of publicity, even if their talent or beauty surpasses their counterparts… However, we have so many resources that our forefathers and mothers didn’t acquire… We have the power and responsibility to learn from our past.’

Perle Noire

There is always the question as to how many performers of colour there needs to be before we feel accurately represented. Taking Britain as an example, the 2011 UK census lists the population of Asians as 7.8%, Black or Black British as 3.4% and people identifying as Mixed or Other are listed at 3% (a total of 14.2% of the UK population). Considering that in the UK I’d estimate there to be, at the most, ten professional burlesque performers of colour out of 150-200 professional Caucasian burlesque performers (roughly 5/6%), the numbers suddenly seem stark in comparison. Some would argue that this is actually quite close to a healthy reflection of the ethnic make-up of our society, but I would disagree. And isn’t burlesque and vaudeville entertainment, by its very nature, meant to transcend society? To help us all escape from the often depressing realities of our day to day lives?

‘Of course, the burlesque community is just a microcosm of the society at large… The frustrating part is reading fluff piece after blog after glowing review that paints burlesque as somehow immune to society’s ills. It isn’t, and the first step toward inclusion might be really facing some hard truths. One truth being that we have work to do, ya know?’

Vagina Jenkins

Having so few performers of colour in the industry can have a direct impact on the mental wellbeing of those few who have taken the plunge; although I’m naturally gregarious and sociable, I’ve sometimes felt isolated backstage, or even awkward and out of place during a curtain call. With our painted faces and bejewelled costumes, it’s easy to feel like a sideshow attraction when you’re the only one in the line-up. Further than this, many performers of colour have experienced being treated differently to the white performers in a show. Some have found out they’re being paid less, had their image left out of promotional material, been mistaken for another performer of colour or been spoken to in an offensive manner backstage. I’ve had producers clicking their fingers and snapping their necks at me, because in their minds that’s what black women do. Or performers I’ve never met before referring to me as ‘bitch’ or ‘girlfriend’ in a misguided attempt to ingratiate themselves with me. It can feel like banging your head against a brick wall trying to carry out your job in a working environment when faced with such unprofessionalism.

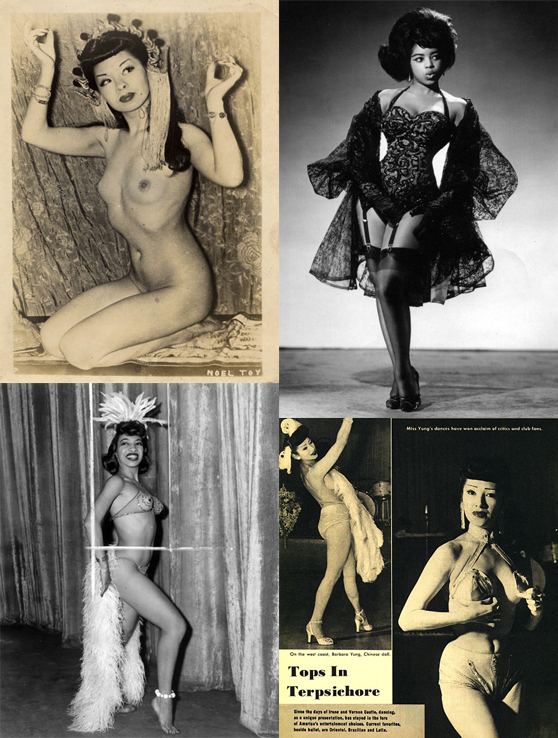

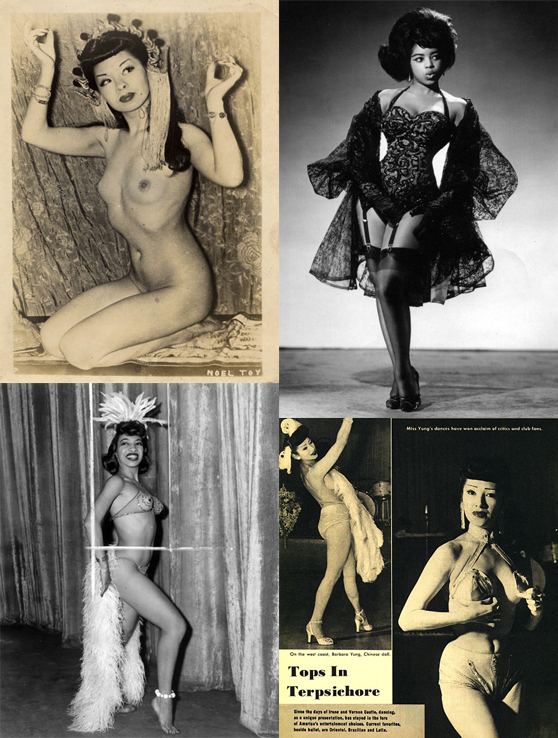

Clockwise, from top left: Noel Toy; Miss Topsy, 1958; Barbara Yung in a 1951 feature; Marie Bryant.

Ray Gunn mentioned ‘the occasional drunken suggestion that I should change my name to something like Ricky Godiva, Jason Blackheart, or Chocolate Chip. Also when they wanted to change the name of our show to Mandingo…’ It can be soul destroying working hard to create a well rounded stage persona and varied repertoire of routines, only to be constantly put back into your neat little box. If I got paid every time I’m asked if I have a Josephine Baker act or if I could do something a bit ‘voodoo-ish’, I’d be typing this article on a yacht in St.Tropez instead of rainy London. The emotions that come with being approached with a race-specific booking are complex; it feels good to have been approached, potential money and, of course, the attention, but you also wonder if you’re just filling in a space or quota; adding a bit of spice to the mix, if you will. In my experience, it can be soul destroying.

‘I have noticed a pattern recently where there are a lot of ‘Shanghai’ themed shows that people are booking me for; they come with the idea of a pan-Asian event and I think people book me because they want an ‘exotic’ feel or look to validate their theme … I have a Charlie Chaplin tribute act too, and I find that when I get booked for this, sometimes people can – for that split moment – see my skill instead of just seeing my ethnicity.’

Marianne Cheesecake

I’m a traditional kind of burlesque gal with a preference towards a classic style, and I personally don’t have any racially themed acts. But I usually don’t get approached by a producer to perform classic burlesque unless I already have a working relationship with them. That’s not to say it doesn’t happen, but believe me, it’s rare. If they’re scouring the internet for a classic performer to add to the line-up, I’m somewhere near the end of their list. It’s more likely I’ll be approached to be part of a ‘jungle exotica’ show or for a corporate event at an ‘urban’ music station.

Charlie Low’s Forbidden City.

And then there’s the general public. In the past, I’ve had audience members approach me after I’d performed to tell me that I was ‘very beautiful, for a black girl’ or that I ‘looked like a tribal queen’. At first I would give them forced smiles, but later this evolved into an eye roll, and as I hardened to the comments I would occasionally send a string of expletives their way that would make a sailor blush. But for the most part, audiences have been complimentary, kind and respectful. And the ones who haven’t been are reacting to the fact that they’ve never been given the option of an ethnically diverse burlesque cast; to them I was an anomaly, an exotic fantasy that they were unlikely to see on stage again. Personal comments like these used to impact me so deeply that they began to change me. Luckily for me – the older I get, the less I care.

Burlesque Legend Toni Elling. (Courtesy of Jo Weldon/Burlesque Daily).

‘It’s challenging for women of colour to gain the ascendancy required to have a sense of ownership of our bodies and safety in them, little less our sexual/sensual expression, given the history of things.’

Chivaca Honeychild

I used to find myself consumed by the thought that, as a black woman performing for a primarily white audience, I might be fetishised by their gaze in a way I couldn’t control. Although I’ve always been the girl grinding on the bar and booty-popping on tables in a nightclub with friends, on stage I used to make a concerted effort not to wind my hips too low or shake my rear too much. Now, as an older and more secure performer, I love to incorporate moves such as whining and twerking into my routines – traditionally black dance styles originating from dancehall and hip hop. I’ve had both negative and positive reactions to this, having been described as ‘too black’, ‘inspiring’, ‘vulgar’ and ‘exquisite’ by a variety of spectators. But I’ll continue to present the type of sexuality on stage that I identify with the most – that of a twenty-something year old black woman raised in London – because that’s what makes me unique. My cultural experiences (music, food, dance, language, history) have all contributed to the way I move, the way I perform, even the way I gesture to the audience to show that I’m intending to look sexy or alluring. And the more performers of colour we’re all exposed to, the more blurred our differences in colour, shape, movement and expression will become. I feel like those of us already involved in the industry owe it to the next generation of performers, producers and audience members to make conscious decisions to change the status quo.

“We all have a part to play in changing the face of burlesque; it’s an art form that we collectively decided to resurrect and we’re the ones keeping it alive. Now we have a responsibility to talk freely with each other and reshape the way it moves forward from here.”

It’s most important for our producers to be more inclusive. Are you hiring the same type of performer for every show? If so, what message do you think you’re sending to your audience about burlesque? And if you are casting a performer of colour, are you promoting their image as prominently as the other cast members? Don’t make the assumption that hiring a few performers of a different ethnicity will give the show a racial bias; your audience is more intelligent than that, so don’t be scared to book more than one of us at a time!

‘It’s a hard pill to swallow when you’re the one receiving standing ovations but you’re not receiving top billing and your image is rarely used. It’s a constant battle.’

Perle Noire

It’s also important for performers, of all racial persuasions, to talk to your producers if you feel the show is lacking in diversity. Last year, I became one of the resident performers at a leading cabaret venue which I had been contacting for close to a year with no response. This was thanks to a small group of ballsy performers who, as well being my friends, believed in my talent and pressured the bookers to meet me and hire me. These performers took the responsibility upon themselves to change the diversity in their own show line-ups.

It’s also down to the audience and fans to speak up about what they want to see; this industry belongs to all of us. Is there a performer you’d love to see at your local burlesque show? Email the organisers – they won’t know unless you tell them.

Perle Noire. ©Kaylin Idora

But to all the black, brown and other girls considering a journey into burlesque, the main responsibility falls on you. Don’t be intimidated by an industry that might look like it’s not for you from the outside; there’s a big gaping hole in the market that needs to be filled, so wiggle your way in and be prepared to hustle very hard. The best piece of advice I could give would be to choose your shows carefully. When I was starting out, I made so many mistakes and bad choices in an attempt to get as much stage time as possible. Sometimes I chose shows that didn’t represent me in a way that made me feel like the cinematic showgirl goddess I had always imagined myself becoming.

If a producer is asking you to perform in a certain style or in a show that reduces you to the colour of your skin – ask questions. You may get the answers you need to put you at ease and if you don’t, then say no. Take it from a performer who loved burlesque, became jaded, retired and then fell back in love with the industry – there will be more opportunities. As a burlesque performer of colour you’re walking uphill already, so if you make the right choices, your walk may be slower but your legs won’t ache nearly half as much.

We all have a part to play in changing the face of burlesque; it’s an art form that we collectively decided to resurrect and we’re the ones keeping it alive. Now we have a responsibility to talk freely with each other and reshape the way it moves forward from here.

Remember the World Jump Day hoax? When we were all apparently meant to jump at the same time to shift the earth out of its orbit and stop global warming? Well maybe we can apply the same principle to our beloved burlesque; if we all push harder at the same time towards a more inclusive and diverse industry then maybe we can achieve it. Let’s start by simply talking about this – loudly and together, all of us.

Thanks to all the performers who contributed their time, experience and opinions to this article: Coco Framboise, Sydni Deveraux, Creatrix Tiara, Vagina Jenkins, Coco Deville, Perle Noire, Kalani Kokonuts, La Cholita, Ray Gunn, Shanghai Pearl, Loulou Champagne. And extra special thanks to Marianne Cheesecake, Trixi Tassels and Chivaca Honeychild for going above and beyond to help me construct this article.