Polari Journal is for writers and readers with affiliations to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Queer (LGBTIQ) communities and cultures. Polari works contrary to the mainstream and revels in the margins. Polari privileges writing by LGBTIQ writers. Polari publishes the best writing by and about LGBTIQ persons. Although Polari celebrates writing that addresses sexuality, sex and gender, it is not confined by those themes. Polari endeavours to showcase emerging, developing and established writers as a means of bringing readers and writers together in mutually enriching ways. This is done in response to widespread neglect of LGBTIQ writing and the near total collapse of Gay and Lesbian publishing. All work appearing in Polari has been selected by a professional editorial committee and is peer-reviewed. Each issue consists of a mix of commissioned and other works that reflect the very best in LGBTIQ writing worldwide.

Open Call for Submission

Polari Journal is currently holding an open call for submissions for its third issue (published April 2011). There is no specific theme for this issue; however Polari tends towards the shorter forms: short stories, poetry, essays, one act plays/scripts and reviews. In general, the word limit for fiction, plays and essays is 6000 words. Reviews should not be more than 1500 words. For poetry, the maximum is 100 lines.

At this time financial remuneration is not offered. All rights remain with the author/s.

The Final Date for submission would normally be January 1st 2011 however this has been extended to February 1st 2011.

Review the Submissions Guide then send all submissions to:

Or directly to the editor: pema.baker@scu.edu.au

=========================================================

|

Before you submit to Polari Journal, please read the instructions below carefully. |

|

|

|

|

Polari endeavours to showcase emerging, developing and established writers as a means of bringing readers and writers together in mutually enriching ways. Polari publishes the best writing by and about LGBT persons. Although Polari celebrates writing that addresses sexuality, sex or gender, it is not confined by those themes.

For the April issue submissions close on January 1st each year. For the October issue submissions close on July 1st each year.

All submissions should include a cover letter that provides name, contact details and any pertinent biographical information (100 words max). You may also include a brief note about any publications history. The cover letter will not be forwarded to referees or the Editorial Collective.

All submissions must be emailed as Word documents to: submit <at> polarijournal <dot> com indicating the genre of the submission in the subject field followed by your surname. For example, for a poetry submission type in the subject field <Poetry Submission Surname> or for a scholarly paper type <Scholarly Essay Submission Surname>.

Word documents must have the submission title in the file extension. For example: The_Lake.doc. Before submitting documents save them with all identifying information (including author tags) removed. To do this in Office 2007, click the Microsoft Office Button, point to Prepare and then click Properties. In the 'Document Information Panel' remove the author name in the Authorbox. Then save your document.

Please do not submit more than 1 short story, essay, review or one act play at a time. You may submit up to 3 poems at a time.Please do not contact us looking for news of your submission. We would prefer you wait for Polari to contact you.

Photography and Visual Art Submissions

Polari Journal showcases photography and visual art from LGBTIQ photographers and artists in the MUSEUM section. If you wish your work to be considered for the MUSEUM section send an enquiry and sample images (no more than 3 or 4) by the due date for each issue to: queries <at> polarijournal <dot> com

Creative Works

Polari Journal publishes creative writing by emerging, developing and established writers. In most cases, preference will be given to writers who have achieved at least one other journal or anthology publication. However, Polari Journal is also committed to publishing exceptional creative work by unpublished authors. All submissions should be typed (double spaced) with at least 30mm margins. Please use 12 point Times New Roman font. We accept most genres however Polari is not an appropriate venue for strong erotica.

Scholarly Works

Polari Journal publishes scholarly work that might be described as Queer Writing - a unique discipline that occupies the intersections between Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Literature Studies, Creative Writing (research, teaching and practice) and Queer Theories. Generally speaking, Polari Journal only publishes scholarly work by authors who have attained a minimum of a Masters qualification. In most cases, preference will be given to authors who have already been awarded a PhD. However, on occassion Polari will publish exceptional scholarly work by authors who are currently undertaking a postgraduate (Masters or PhD) program.

Scholarly Citation Style

Scholarly essays should adhere to the Chicago Manual of Style. Specifically, references and documentation within all reviews/essays should follow the Chicago Documentation Style I.

A Call for Papers: Contemporary African Literature

This looks interesting. Kenyan writer and critic J.K.S Makokha, who teaches at the Free University of Berlin, Germany, and Leonard Acqauh of University of Cape Coast, Ghana, will be co-editing a book entitled CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN LITERATURE:

THEMATICS AND CRITICISM (2011).This project comes at a time when a new wave a young African writers have seized the attention of the world, often departing from the thematic concerns of classic writers like Ngugi, Mungoshi, Achebe, and sometimes adding to the trajectory of concerns that have been implicit in African literature from the outset. A book like this promises to show the diversity of the literature, to give the world a taste of the literature in the new century, and, indeed, as the information below shows, the focus of the work is on writing published since 2000. Below is the announcement in full:We are seeking critical essays for a new edited volume on major works of African literature by new writers emerging after 2000 or by established writers but published after 2000AD. Contemporaries of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Ngugi represent the two age groups of African writers. We are interested precisely in new critical essays focusing on themes and thematics in the new works of these two writers and/or their African contemporaries across the continent or living in Diaspora.

The first decade of the 21st Century has just ended affording critics with the window for retrospection needed in order to ensure objectivity in our critical enterprise as set out in the intention of this project. The aim of this celebratory collection of new essays is to offer emergent critical perspectives on the concerns highlighted in the exciting new literary output of African writers after the fin de siècle. The works under study should be in English or in other Afrophone or Europhone languages with English translations.

The contributions should be original and couched in relevant and current theories and frameworks of literary interpretation. Essays on new African literature that are related to the broad focus of the collection (i.e. theory of literature) and move beyond specific cases in an attempt to expand the discussion within a theoretical perspective are highly encouraged; the role of African literature or writers can be two good points of such a broad focus. Contributions are invited on essays that explore any of the following topics/themes/ideas in prose, poetry or play genres. Moreover, we explicitly invite contributions on topics or thematics not mentioned below but still fitting under this book project title above:

1. Representing the Diaspora

2. Gender

3. Memory and Hybridity

4. Cultural translation

5. Borderland subjectivities

6. Translocation and multilocality

7. Migration and nomadology

8. Multicultural and/or multilingual writing (narratives)

9. Traveling Selves

10. Maps and Mapping

11. Postmodernism and Postcolonialism

12. Genre Criticism

13. Politics of Writing/ Cultural Politics

14. Democracy and Governance

15. African Renaissance and new Pan-Africanism

16. Urbanization and CosmopolitanismNB: Send us a short abstract of 300 words via the email adds below by February 14, 2011

JKS Makokha - makokha@zedat.fu-berlin.de copy to jksmakokha@yahoo.com and

Leonard Acquah - leoacquah@yahoo.comThe book will be published in 2012. Kindly note the important dates below:

1. February 14 ? February 28, 2011 ? Assessment and Selection of Abstracts.

2. March 1, 2011 ? Notification of Acceptance.

3. March 5, 2011 - July, 5 2011 ? Writing and Submission of Article.

4. July 5, 2011 ? August, 5 2011 ? Blind Peer Review Process.

5. August 5, 2011 ? October 5, 2012 ? Revision of Articles in line with Peer Review Reports.

6. October 6, 2011 ? Deadline of Submission of revised articles.

7. December 5, 2011 ? Submission of Complete Book Manuscript to Publishers.

The formatting guidelines will be sent on March 1, 2011 to the authors of the selected abstracts.

Why You Should Send Us Your Best Work

- Because we read submissions carefully and thoughtfully. Readers for all genres are faculty members in addition to MFA candidates enrolled in a publishing practicum under the guidance of Peter Oresick, who has spent 23 years in the publishing industry. Each submission to The Fourth River is read multiple times by at least two different readers, and editors regularly read stories from slush and rejection piles to ensure submissions aren’t overlooked.

Because writers published in The Fourth River are in good company. Our past or upcoming issues feature stories, poems and essays by Michael Byers, Ander Monson, W.E. Butts, Rick Campbell, and Lori Jakiela. Contributors to The Fourth River have received Pushcart Prizes, NEA Fellowships, and numerous other awards. Our contributors have published in Birmingham Poetry Review, Glimmer Train, Alaska Quarterly Review, Witness, and The Missouri Review; they have been anthologized in Best American Short Stories, The O. Henry Prize Stories, and Best American Travel Writing. We also encourage unpublished or emerging writers to submit—there is perhaps no greater badge of honor for an editor than to claim, “We first published ________ right before his/her career rocketed into the literary stratosphere.”

The Fourth River’s theme, an extension of Chatham University’s MFA Program, is writing that “explores the relationship between humans and their environments, both natural and built, urban, rural or wild.” This unique theme is a wide net that attracts a variety of different voices and viewpoints. Consider these three writers from Issue 6’s contributors’ notes: Astrid Cabral, “a leading poet and environmentalist from the Amazonian region of Brazil”; Derek G. Handley, who “served 10 years, 10 months, and 6 days in the United States Navy as an aviator and public affairs officer”; and Laila al-Atrash, “A TV producer and news editor, she writes a regular column for the Jordanian daily Al-Dustour…Al-Atrash holds degrees in Law and Arabic Literature.” Other writers featured in that issue include a soccer coach from New Jersey, a former merchant seaman, and a Brazilian songwriter.

Our staff consists of artists and professionals. Our editors have work published or forthcoming in The Kenyon Review, Bellevue Literary Review, The Gay & Lesbian Review, Literary Review, Connecticut Review and Iowa Review. The Fourth River’s editors have received fellowships from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, the Raymond Carver Short Story Award, and a Pushcart Prize nomination. Poetry editor Heather McNaugher and Editor-in-Chief Peter Oresick have published several chapbooks—at least eight between the two of them. Executive Editor Sheryl St. Germain has published six books of poetry and one book of lyric essays.

We’re a print journal. Which, of course, doesn’t make us better than online journals, but we like the fact that our contributors’ work appears in a pleasant eco-friendly book that, between readings, will grace perhaps thousands of bookshelves and coffee tables. Chatham’s MFA Program is rising, and with it, we know The Fourth River will continue to grow in prominence and circulation.

As editors, there is no greater thrill than discovering a piece that quickens the pulse, that challenges us, that changes the way we view our surroundings. Just like you, we work hard at this, and we look forward to reading your best work.

Submission Guidelines

The Fourth River accepts unpublished poetry, literary short fiction, and creative nonfiction. Please send up to seven poems or up to 7,000 words of prose.

- Reading Period: September 1 – February 15.

- Postal submissions only. Email submissions are deleted unread.

- Include a cover letter with contact info along with the title and genre of the submission. We accept simultaneous submissions if indicated on the cover letter; please let us know immediately if a piece is accepted elsewhere.

- All manuscripts must include a SASE (for response only). We recycle all manuscripts we receive; please do not send your only copy.

- We don’t publish writing for children or Young Adult audiences.

Submission Address

(Poetry, Fiction, Nonfiction) Editor

The Fourth River

Chatham University

Woodland Road

Pittsburgh, PA 15232Contact Us

For more information, contact us at 4thriver[at]gmail[dot]com.

Accepted authors receive two contributor's copies of the journal.

Joyce Gordon Reading

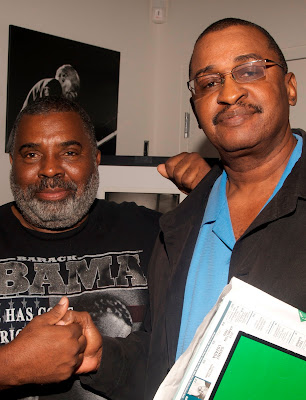

Bay Area Writers/activists honor slain Oakland Post Editor Chauncey Bailey outside Joyce Gordon Gallery

Journal of Pan African Studies

Journal of Pan African Studies

Poetry ReadingBay Area Poets Read their Entries

Joyce Gordon Gallery, 14th and Franklin, downtown Oakland

Saturday, February 19, 3-6p

Al Young, California Poet Laureate EmeritusParadise Jah Love

Phavia Kujichagulia

Ptah Allah El

Senior Editor, JPAS

Fritz Pointer

J. Vern Cromartie

Ishmael Reed

Anthony Spires

Not pictured: Kwan Booth, Charles Blackwell, Niyah X, Maisha, Nykimbe, Ramal Lamar, Aries Jordan

Joyce Gordon Gallery

14th and Franklin, downtown Oakland

presents

Academy of da Corner

Reader's TheatreSaturday, February 19, 3-6pm

Reading from

The Journal of Pan African Studies, Poetry Issue

Guest Editor Marvin X

Marvin X has always been in the forefront of Pan African writing. Indeed, he is one of the innovators and founders of the revolutionary school of African writing. --Amiri BarakaAn excellent collection of poetry from some of the best poets in America. The best selection of poems that any Guest Editor has ever put together!--Rudolph Lewis, Editor, Chickenbones.com

An Academy of da Corner Reader's Theatre

production, 14th and Broadway, downtown Oakland

Black Bird Press

Journal of Pan African Studies

Joyce Gordon Gallery

Refa I

Oakland Post Newspaper Group

Media: Gregory Fields, Adam Turner, Ken Johnson, Khalid Wajjib, Kamau Amen Ra, Gene Hazzard, Lee Hubbard, Wanda SabirThe Journal of Pan African Studies will be on sale at the event, 475 pages, $49.95. It is available online as well. www.jpanafrican.com

Information: jmarvinx@yahoo.com

Guest Editor's Notes on the Journal of Pan African Studies, Poetry IssueIf one is serious about getting a precise understanding of the 1960s Black Arts Movement, the most radical artrs and literary movement in American history, that forced the inclusion of ethnic literature into academia, one must grab the recent Journal of Pan African Studies, Poetry Issue.

The issue has poems by some of the BAM major players (Baraka, Bullins, Madhubuti, Ya Salaam, Toure, and X, as well as essays and dialogue on the literary productions of BAM, the proposition that the genre called Muslim American literature is based on the BAM Islamic influence, with roots in Moorish Science, Nation of Islam, Sufic, Sunni and Yoruba influences, although the Yoruba is not explained yet self evident in the poetry.

There is discussion on the poetic mission, and in the BAM tradition it is argued that poetry is not an end within itself but a vehicle, a tool, a weapon in the arsenal of liberation, and most importantly, a tool of communication.

The poems are drums of Pan Africa, message to and from the God and gods, ancestors, the living and yet unborn. Entries are from Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Kenya, United Kingdom, South Korea, New Zealand and throughout the United States.

We tried to give a regional sample from the west coast, east coast, mid west and south. You will find a commonality of themes and concerns, freedom most of all, but listen carefully to the regional rhythms on the poetic drums.

Overall, it represents an alternative world view, the Pan African world view as opposed to the Eurocentric world view. It is the world view of the oppressed, yet the spiritually liberated for the poets are, if nothing else, free spirits that cannot be caged, whipped or defeated, for they say you can kill the revolutionary but can't kill the revolution, thus the word causes forward motion in the ocean of humanity, and such are the contents herein. Magic words, magic truths, wisdom and and prophesy.

It is obvious from the bios that most of the poets are trained in academia, whatever their other origins. For sure the nuances of language transcends traditional English, for it is a language rooted in decolonizaton and liberation. Thus, many of the poets are bilingual, making use of the master's tongue and the tongue of the masses.

The BAM theme of revolutionary consciousness is pervasive. Associate Guest Editor Ptah Allah El says this is the Bible for the 21 Century. So it is! Like Black Fire of the 60s, let it fire up a static situation with the word. Let the Pan African mind move a little closer to home.

--Marvin X

1/15/11

Bradley Manning and GI Resistance to US War Crimes

Saturday 15 January 2011

by: Angola 3 News, t r u t h o u t | News Interview

Independent journalist Dahr Jamail spent nine months reporting directly from Iraq, where he followed the US invasion in 2003. His stories have been published by Inter Press Service, Truthout, Al Jazeera, The Nation, The Sunday Herald in Scotland, The Guardian, Foreign Policy in Focus, Le Monde Diplomatique, The Independent and many others. Dahr reports for Democracy Now! and has appeared on Al Jazeera, the BBC, NPR and numerous other television and radio stations around the globe.

Jamail is the author of two recent books: "Beyond the Green Zone: Dispatches From An Unembedded Journalist" (2008) and "The Will to Resist: Soldiers Who Refuse To Fight in Iraq and Afghanistan" (2009). He also contributed Chapter 6, "Killing the Intellectual Class," for the book "Cultural Cleansing in Iraq: Why Museums Were Looted, Libraries Burned and Academics Murdered" (2010). Learn more atwww.dahrjamailiraq.com.

Angola 3 News: On April 4, 2010, WikiLeaks released aclassified 2007 video of a US Apache helicopter in Iraq firing on civilians and killing 11 people, including Reuters photojournalist Namir Noor-Eldeen and his driver, 40-year-old Saeed Chmagh. No charges have been filed against the US soldiers involved.

In sharp contrast, a 22-year-old US Army intelligence analyst named Bradley Manning has been accused of leaking the classified video. Arrested in May and facing up to 52 years in prison for a range of charges, Manning is now being held under what lawyer and journalist Glenn Greenwald has termed "inhumane conditions."

Manning's support website declares that "exposing war crimes is not a crime." Indeed, the Nuremberg Laws, established after the horrors of World War II, declare that soldiers have a legal obligation to resist criminal wars. Let's take a closer look at this issue of US war crimes. What do you think are the strongest arguments that have been made for why the US invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan are criminal?

Dahr Jamail: To be clear, while I've covered Iraq extensively, I've not covered Afghanistan. Thus, I'll keep all my answers in the context of my expertise, that being Iraq.

That said, the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq could not have more clearly violated international law. Even the former secretary general of the United Nations (UN), Kofi Annan, said in September 2004 that the Iraq war was illegal and breached the UN Charter.

An illegal war is thus the mother of all war crimes, for from that stems all the rest. What I've seen in Iraq has been a parade of war crimes committed by the US military: rampant torture, collective punishment (Fallujah is an example), deliberate firing on medical workers, deliberate killing of civilians for "sport" and countless others.

Then, there is the fact that both occupations are so clearly about the control of dwindling resources and their transport routes, that the excuses given for them by the US government (by both Bush and Obama) are both laughable and insulting to anyone capable of a modicum of critical thought.

A3N: How do you rate the corporate media's coverage of the Bradley Manning story?

DJ: It's been a farce, a classic case of shoot the messenger. When someone becomes a soldier, they swear an oath to support and defend the US Constitution by following "lawful" orders. Thus, they are legally obliged by their own oath to not follow unlawful orders. What Manning did by leaking this critical information has been to uphold his oath as a soldier in the most patriotic way. Now, compare that with how he has been raked over the coals by most of the so-called mainstream media.

A3N: How do they address the argument that exposing war crimes is not a crime?

DJ: Usually they don't, because the corporate media - and the government, for that matter - avoid the words "war crime" as though they are a plague. Thus, they avoid the issue at all cost.

A3N: In your opinion, how do the corporate media present the US occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan to the US public?

DJ: With Iraq, the occupation is presented as though it was a mistake, as though the great benevolent US empire was mistakenly mislead into the war, but since "we" are there, it is good that at least Saddam Hussein has been removed - and now, of course, the US has only done the best it can in a tough situation.

With Afghanistan, the occupation is presented to the public as the ongoing frontline battle against "terrorism," while in reality, they should call Afghanistan "pipeline-istan" because it's all about securing the access corridors for natural gas and oil pipelines from the Black Sea through Afghanistan - the four main US bases there are located along the exact pipeline route - to the coast of Pakistan.

A3N: How does the corporate media narrative contrast with what you have seen firsthand in Iraq?

DJ: The difference is night and day. The whitewashing and outright lying by the corporate media is offensive to me. It is repulsive, in fact, when compared to what the reality on the ground is in Iraq. The brutality of the US military there against the civilian population would shock people. More than 1 million Iraqis have been slaughtered because of the US occupation. As you read this, you can know that one in every ten Iraqis remains displaced from their homes. Can you imagine that? The US policy in Iraq has been so destructive that one out of every ten Iraqis is currently displaced from his or her home, seven years into the occupation.

A3N: Returning now to the issue of soldier resistance, what are the various reasons that antiwar soldiers give as motivation for their opposition to the occupations?

DJ: These reasons mostly come from what the soldiers see once they arrive in the occupation: the buckets of money being made by the contractors, the lack of goals for the occupation beyond generating huge amounts of profit for war contractors and the reasons given for the invasion and occupation being entirely false. So, most seem to become antiwar when they see that they've been lied to, used, betrayed, and that they are putting their lives on the line so that war contractors can get richer.

A3N: What are some of the ways that antiwar soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan have resisted?

DJ: Myriad ways. The most common, and least dramatic, is going AWOL [absent without leave]. More than 60,000 soldiers have now taken that route since September 11, 2001. So, often, folks will go do a deployment, come back for a break, then simply not show up when it's time for their unit to redeploy.

Some of the more interesting means of resistance I've found entailed doing what soldiers refer to as "search and avoid" missions. One soldier told me how they would go out to the end of their patrol route in their Humvees, find a big field and park. They'd call in to base every hour to check in and say, "We're fine, we're still searching this field for weapons caches." And they would sit there doing nothing until the time was up for their patrol, and they'd return to base. I met more and more soldiers who shared similar stories, from all over Iraq, during different times of the occupation. That's when I realized how low morale was and how widespread different kinds of resistance had become.

Other soldiers found out how to manipulate their locator beacon on the GPS unit in the Humvees, so they'd sit and have tea with Iraqis while someone moved their beacon around so their base thought they were patrolling.

A3N: How has US military leadership responded to this resistance?

DJ: They don't know about much of it when it's happening, although there have been times when a unit has been caught doing something like the aforementioned, and they've broken up the unit, but that has been quite rare overall.

With AWOL troops, the military doesn't have the manpower to send their MP's [military police] after them, so the military lets them go and waits for them to get a traffic ticket, for example. Then the cops hand them over to the MPs, who throw the AWOL soldiers in the brig to await a court-martial. Then, often, the soldier is told he or she can go back to Iraq or Afghanistan, or he or she will be court-martialed.

A3N: In your book "The Will to Resist," you document many different cases of soldiers that faced criminal charges for their opposition to US wars. We discussed Bradley Manning's case earlier in this interview, but can you please tell us about any other recent, ongoing cases that have begun since the publication of your book in 2009? How can our readers best support these soldiers?

DJ: Most of the cases I followed that took place after my book was published have been completed: time was served by the soldiers, and then they were released into freedom from the military. Two cases of this type really stand out: Victor Agosto and Travis Bishop. Both of these men stood up and refused to be deployed, were court-martialed, served their time and are now free.

There will be more to come as these occupations persist. A group to follow that regularly supports these resisters is Courage To Resist. They are based in Oakland, California, and are run by Jeff Paterson, himself a resister to the first Gulf War. They do a great job of tracking resisters and what folks can do to support them. Support includes donations, but also making phone calls, writing letters and other forms of activism.

A3N: In the months leading up to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the antiwar movement in the US was relatively strong, but since the invasion began, the antiwar movement seems to have lost considerable momentum and strength. On a practical level, what do you think the US antiwar movement needs in order to be reenergized and finally end these wars?

DJ: At the risk of sounding like a cynic when I feel I'm making an honest assessment, I don't feel there will be a mass organization of an antiwar movement. We already live in a police state. What is left of the antiwar movement is completely infiltrated and is being torn apart by sectarianism and profiteering, or the peace-industrial complex.

In addition, I feel that the main reason for the failure of the antiwar movement is that most folks involved in it still believe they can work within the system to generate change, when the system is completely corrupted already. By "system," I mean the federal government. That apparatus is broken beyond repair. It is completely corrupted and needs to be dissolved. Thus, any movement that seeks to work within the parameters set by the system - such as weekend permitted demonstrations, thinking you can effectively pressure your representative, etcetera - is doomed before it begins, because it is still playing by the rules set out by those in power. Rules guarantee never to jeopardize the loss of power by those who hold it.

Only truly radical actions - those meant to subvert the system and shut it down to a point where business as usual is impossible until demands are met - are all that is left.

Who Let 'Baby Doc' Duvalier Back into Haiti?

Jean-Claude Duvalier, the former Haitian leader known as 'Baby Doc', makes his way through the Karibe Hotel in Port-au-Prince on Jan. 16, 2011

(See pictures of Haiti's cholera outbreak.)

All the country needed now was the return of a brutal exiled dictator.

This being Haiti, whose chronic tragedy is so often served with a helping of banana-republic bizarreness, that's what it got Sunday afternoon when Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier landed in Port-au-Prince for the first time since being thrown out of the country and packed off to France almost 25 years ago. "I came to help my country," the 59-year-old former despot declared as some 2,000 of his supporters met him at the airport. But it's hard to imagine how Duvalier's reappearance, which Haitian officials insist took them by surprise, could do anything more than throw Haiti into even deeper turmoil as it tries to rebuild after last year's disaster.(See TIME's exclusive pictures from the Haiti earthquake.)

And what's perhaps even harder to imagine is how the government of French President Nicolas Sarkozy could have allowed Duvalier, who arrived from Paris, to board an Air France flight bound for Haiti under the current circumstances. "For the French to have even permitted [Duvalier] to leave their territory amidst an electoral and cholera crisis here shows they have not much interest in the welfare of the Haitian people," says a high-ranking Haitian government official.

French officials, who technically had no power to stop Duvalier, weren't responding to that question on Sunday night. But Port-au-Prince media were rife with conflicting conspiracy theories — all of them focused on last week's election report by the Organization of American States (OAS). It concluded that Jude Célestin, the candidate of Haitian President René Préval's party, actually finished third, not second, in the first-round balloting on Nov. 28, and that Célestin should therefore not be eligible for a runoff vote — which, ironically, was originally supposed to have been held Sunday but has been postponed.(See TIME's photo-essay "Haiti One Year Later.")

The less-than-credible Nov. 28 results, which many if not most Haitians believe the government fixed to eke out a runoff spot for Célestin, were met by violent street protests last month. Even before last week's OAS report, the aloof and unpopular Préval was under ample international pressure, including from the U.S., to recognize the official third-place finisher, Michel Martelly, as the actual runner-up. (He would then face first-place candidate Mirlande Manigat in the runoff.) Last week, France's ambassador to Haiti, Didier Le Bret, was frequently on Haitian radio calling on Préval to respect the OAS recommendation. Préval in turn angrily charged France and the international community with imperialist-style strong-arming.

The question now is, Who if anyone in this standoff benefits from the sudden presence of Duvalier? Some Haitian pundits on Sunday said it might be meant to compel Préval to acquiesce to international demands to sacrifice Célestin. But it's hard to believe, even under Sarkozy, that France and the international community would stoop so low diplomatically as to encourage Duvalier to return to Haiti for that purpose. Others suggested that Duvalier's return instead gives Préval leverage by showing the international powers how much more turbulent things can get if they keep messing with the Haitian President. But again, could even Préval be cynical enough to open the door to one of the 20th century's most notorious dictators for that kind of political gain? Either way, sources close to Duvalier told reporters Sunday that he'd entered Haiti on a diplomatic passport — but if so, it was unclear which country had issued it to him.(See the early days of Baby Doc's life in exile in France.)

What's worse, this drama could actually send many Haitians, albeit with blinders on, to the side of Duvalier, whose stunning return might make him seem a figure of stability and order amid their country's nightmarish uncertainties. Baby Doc had already announced his desire to return to Haiti in 2004, after the ouster of populist President Jean-Bertrand Aristide (whose supporters may now clamor more loudly for his own return from exile in South Africa). Duvalier even said he wanted to run for President himself in the 2006 elections. But Haitian officials made it clear that if Duvalier did return, he'd face trial on charges of corruption and brutality during his 15-year dictatorship, which had succeeded the even harsher regime of his father, François "Papa Doc" Duvalier, who died in 1971.(See the death and legacy of Papa Doc Duvalier.)

Both Papa Doc and Baby Doc ruled through terror, relying on bloodthirsty enforcers like the Tonton Macoutes, and each stole the western hemisphere's poorest nation blind. After Baby Doc and his infamously venal wife, Michèle Bennett, were whisked out of Haiti in February of 1986 on a U.S. Air Force plane amid a seething uprising by Haitians, they settled in the south of France and lived in one of the world's most luxurious exiles. (They divorced in 1993; Duvalier arrived in Port-au-Prince on Sunday with his new wife, Véronique Roy, the granddaughter of a former Haitian President.)(Comment on this story.)

Baby Doc apologized for his government's "errors" in 2004. But despite the welcome he received at the Port-au-Prince airport, Haitian police officials said they were "waiting for instructions from prosecutors" as to whether they should arrest him. After stepping off his Air France flight on Sunday, Duvalier declared, "I am here to see how the situation is." Please. He already knew how bad the situation was. And just as he and his monstrous father did when they ruled Haiti, he's there to make it worse.

— With reporting by Jessica Desvarieux / Port-au-Prince

From TIME's archive: a visit with the 20-year-old "President for Life" of Haiti.

Read "Haiti's Quake, One Year Later: It's the Rubble, Stupid!"

Read more: http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2042762,00.html#ixzz1BM5dBamm

>via: http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2042762,00.html

__________________________

Posted on 17. Jan, 2011 by Ezili Dantò in Blog

Ezili Dantò’s Note on the arrival ofJean Claude Duvalier into Haiti today

Bay kou blye, pote mak sonje – the one who gives the blow, forgets. The one who bears the mark remembers: Over 60,000and some say as high as nearly 100,000 Haitians were murdered under the bloody US-supported Duvalier (father/son) dictatorships from 1957 to 1986. Browse the galleries of the Fort Dimanche website for stories and pictures of the dead — those political prisoners who were imprisoned, tortured and killed at Fort Dimanche“Throughout the blood-drenched rule of the Duvaliers (nearly 100,000 killed by the Tontons Macoutes alone), the US barely uttered a peep about human rights violations. In 1986, however, when it became apparent that Baby Doc’s presidency could not in fact be sustained for his entire life (unless he died soon), the Reagan administration airlifted him to a retirement villa in France and started talking about the “democratic process.” ( From The CIAs Greatest Hits, by Mark Zepezauer.”)

Why would the world’s most powerful nation, the United States, allow this?

Well, their pillage of poor Haiti is butt-naked right now. At the one-year anniversary of the Haiti earthquake, even the conservative media is talking about the failure of US aid, the UN and the NGO poverty pimping business in Haiti. Thus, the UN, as US proxy, needs to justify its job in Haiti. These folks think of us-Haitians as simplistic animals, so why not set up what’s worked for them in other parts of the world? The bringing back of Jean Claude Duvalier, Haiti’s bloody dictator, is, in their plantation minds, sort of like setting up a Hutu/Tusti thing (Duvalier/Lavalas), a civil war in Haiti, an insecurity to bring “order” to.

Bill Clinton, the poverty-pimp-NGOs, the repugnant UN and the foreign-imposed-IHRC need to distract the world from the donation dollars that’s being pocketed or not collected, so hey, let’s rack up the colonial narrative – remind everyone of those “anti-democratic Haitians not ready for the same standards” as the rest of the “civilized” world. Those infighting, violent, illogical Haitians in love with dictatorship! Why not set up the chess board, right before Feb. 7th – the 25th anniversary of the ouster of Jean Claude Duvalier, bring him back to push the two OAS/Duvalierist candidates – Manigat and Martelly (Sweet Mickey), so everyone can forget about the masses wishes, their total disenfranchisement, the 300,000 dead in 33 seconds and those 1.5million still homeless without sanitation, shelter, clean water; the return of President Aristide; the international fraud since 2004; these imposed UN/US elections. and the UN-imported cholera…We’re just puppets the International community , led by the U.S., are moving around their own battlefield. Haiti is not in control. Haitians are not in control. Air France and American Airlines can land anyone in Haiti.

If Air-France wanted to bring in Osama bin Laden into Haiti, how could Haitians stop it? Still, we-Haitians will be blamed, as usual, for all the outrageous acts the wealthy powers-that-be do in Haiti. The “Friends of Haiti” continue with their macabre plan to further destabilize and exacerbate Haiti’s already agonizing sufferings.

But it’s our fault also, we-Haitians sit around reacting, waiting for THEM to act so we can react. Waiting for the OAS to tell us it didn’t make a mistake and the not fair, not free, non-inclusive Nov. 28 elections it helped orchestrate is not toofraudulent and illegal. HLLN wanted to go to Haiti and make a public statement about the fraudulent elections, we could not get any real support. It’s their play and their game, we’re just consumers of this abomination!

Thank you for this “change” President Barack Obama!

Ezili Dantò for HLLN,

January 16, 2011

Nou se rozo, nou pliye nou pa kase

*Nou se roz, nou pliye nou pa kase: Strong winds may bend the bamboo tree all the way down to the ground, but it snaps right back up. It doesn’t break, no matter how strong the wind. So, Haitians have a saying – “Nou se rozo. Nou pliye, nou pa kase “ – like the bamboo tree, we bend but we don’t break; like the flexible ba mboo tree we-Haitians use even the momentum of our falls to stand back up.

>via: http://www.ezilidanto.com/zili/2011/01/obamas-change-in-haiti-the-return-of-d...

The brutal truth about Tunisia

Bloodshed, tears, but no democracy. Bloody turmoil won’t necessarily presage the dawn of democracy

Monday, 17 January 2011

AP - What's left of the face of ex-president Zine el- Abidine Ben Ali stares out from a torn poster in Tunis yesterday

The end of the age of dictators in the Arab world? Certainly they are shaking in their boots across the Middle East, the well-heeled sheiks and emirs, and the kings, including one very old one in Saudi Arabia and a young one in Jordan, and presidents – another very old one in Egypt and a young one in Syria – because Tunisia wasn't meant to happen. Food price riots in Algeria, too, and demonstrations against price increases in Amman. Not to mention scores more dead in Tunisia, whose own despot sought refuge in Riyadh – exactly the same city to which a man called Idi Amin once fled.

If it can happen in the holiday destination Tunisia, it can happen anywhere, can't it? It was feted by the West for its "stability" when Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali was in charge. The French and the Germans and the Brits, dare we mention this, always praised the dictator for being a "friend" of civilised Europe, keeping a firm hand on all those Islamists.

Tunisians won't forget this little history, even if we would like them to. The Arabs used to say that two-thirds of the entire Tunisian population – seven million out of 10 million, virtually the whole adult population – worked in one way or another for Mr Ben Ali's secret police. They must have been on the streets too, then, protesting at the man we loved until last week. But don't get too excited. Yes, Tunisian youths have used the internet to rally each other – in Algeria, too – and the demographic explosion of youth (born in the Eighties and Nineties with no jobs to go to after university) is on the streets. But the "unity" government is to be formed by Mohamed Ghannouchi, a satrap of Mr Ben Ali's for almost 20 years, a safe pair of hands who will have our interests – rather than his people's interests – at heart.

For I fear this is going to be the same old story. Yes, we would like a democracy in Tunisia – but not too much democracy. Remember how we wanted Algeria to have a democracy back in the early Nineties?

Then when it looked like the Islamists might win the second round of voting, we supported its military-backed government in suspending elections and crushing the Islamists and initiating a civil war in which 150,000 died.

video platformvideo managementvideo solutionsvideo player

No, in the Arab world, we want law and order and stability. Even in Hosni Mubarak's corrupt and corrupted Egypt, that's what we want. And we will get it.

The truth, of course, is that the Arab world is so dysfunctional, sclerotic, corrupt, humiliated and ruthless – and remember that Mr Ben Ali was calling Tunisian protesters "terrorists" only last week – and so totally incapable of any social or political progress, that the chances of a series of working democracies emerging from the chaos of the Middle East stand at around zero per cent.

The job of the Arab potentates will be what it has always been – to "manage" their people, to control them, to keep the lid on, to love the West and to hate Iran.

Indeed, what was Hillary Clinton doing last week as Tunisia burned? She was telling the corrupted princes of the Gulf that their job was to support sanctions against Iran, to confront the Islamic republic, to prepare for another strike against a Muslim state after the two catastrophes the United States and the UK have already inflicted in the region.

The Muslim world – at least, that bit of it between India and the Mediterranean – is a more than sorry mess. Iraq has a sort-of-government that is now a satrap of Iran, Hamid Karzai is no more than the mayor of Kabul, Pakistan stands on the edge of endless disaster, Egypt has just emerged from another fake election.

And Lebanon... Well, poor old Lebanon hasn't even got a government. Southern Sudan – if the elections are fair – might be a tiny candle, but don't bet on it.

It's the same old problem for us in the West. We mouth the word "democracy" and we are all for fair elections – providing the Arabs vote for whom we want them to vote for.

In Algeria 20 years ago, they didn't. In "Palestine" they didn't. And in Lebanon, because of the so-called Doha accord, they didn't. So we sanction them, threaten them and warn them about Iran and expect them to keep their mouths shut when Israel steals more Palestinian land for its colonies on the West Bank.

There was a fearful irony that the police theft of an ex-student's fruit produce – and his suicide in Tunis – should have started all this off, not least because Mr Ben Ali made a failed attempt to gather public support by visiting the dying youth in hospital.

For years, this wretched man had been talking about a "slow liberalising" of his country. But all dictators know they are in greatest danger when they start freeing their entrapped countrymen from their chains.

And the Arabs behaved accordingly. No sooner had Ben Ali flown off into exile than Arab newspapers which have been stroking his fur and polishing his shoes and receiving his money for so many years were vilifying the man. "Misrule", "corruption", "authoritarian reign", "a total lack of human rights", their journalists are saying now. Rarely have the words of the Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran sounded so painfully accurate: "Pity the nation that welcomes its new ruler with trumpetings, and farewells him with hootings, only to welcome another with trumpetings again." Mohamed Ghannouchi, perhaps?

Of course, everyone is lowering their prices now – or promising to. Cooking oil and bread are the staple of the masses. So prices will come down in Tunisia and Algeria and Egypt. But why should they be so high in the first place?

Algeria should be as rich as Saudi Arabia – it has the oil and gas – but it has one of the worst unemployment rates in the Middle East, no social security, no pensions, nothing for its people because its generals have salted their country's wealth away in Switzerland.

And police brutality. The torture chambers will keep going. We will maintain our good relations with the dictators. We will continue to arm their armies and tell them to seek peace with Israel.

And they will do what we want. Ben Ali has fled. The search is now on for a more pliable dictator in Tunisia – a "benevolent strongman" as the news agencies like to call these ghastly men.

And the shooting will go on – as it did yesterday in Tunisia – until "stability" has been restored.

No, on balance, I don't think the age of the Arab dictators is over. We will see to that.

Like Robert Fisk on The Independent on Facebook for updates

Crossroad for Arab Dictators

Something amazing and remarkable happened in Tunisia this week which is sending a tidal wave of expectations throughout the Arab and Islamic worlds. The Tunisian people overthrew a dictator who had been in power for 23 years. No Arab country has done so before. Other Islamic countries, Iran in 1978 and Pakistan in 2008, have seen dictators overthrown by civil unrest but never in the Arab world. The big question is who is next? And the answer may be Egypt. Zine al Abidene Ben Ali was Tunisia's secret police boss when he orchestrated a bloodless coup in 1987. He had been the power behind the scenes for some time before the coup. During his tenure he brought stability and some economic growth but ruthlessly suppressed dissent and labeled almost all opponents as Islamic extremists.

Photos: Tunisia's Uprising

After his ouster, Ben Ali apparently wanted to find refuge and exile in France, which has a large Tunisian émigré population. But Paris said no thanks, fearing his presence would exacerbate tensions with the country's large Muslim population. So Ben Ali is in Saudi Arabia, which has a long tradition of offering asylum to ousted Muslim leaders. The kingdom takes them in on the proviso that they stay out of politics.

Is Tunisia a harbinger of change elsewhere? Certainly the problems that brought down Ben Ali can be found elsewhere in the Arab world. High unemployment and even higher underemployment—especially among restless young men—in a period of rising food and energy prices and global economic downturn characterize virtually every major Arab country from Morocco to Yemen. Several are also led by regimes that are long in the saddle. Tunisia's immediate neighbors Algeria and Libya both fall into this category.

The joke in Cairo this weekend was whether Ben Ali's plane would stop in Cairo to pick up Mubarak.

But the big question mark is Egypt. With the Arab world's largest population and biggest intelligentsia, Egypt has been run since 1981 by Hosni Mubarak. Mubarak, 82, came to power in a hail of bullets when his much more flamboyant and charismatic predecessor Anwar Sadat was assassinated by a band of four jihadists in the Egyptian army during a parade marking the anniversary of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. I was the chief of the Egypt desk in CIA that day and assured a worried Reagan administration that Mubarak would hold onto power. I was right for thirty years.

Mubarak has held on to power ever since that October day and has never appointed a Vice President to be a successor. He has brought remarkable stability to Egypt despite fighting a bitter and bloody battle with jihadist terrorists led by Ayman Zawahiri, the number two in Al Qaeda, in the 1990s. But stability has led to lethargy and stasis. Egypt, once a leader in the Arab world and the Islamic world, has fallen to a being a backwater.

Mubarak has flirted with the idea that his son, Gamal, might succeed him—but has also suggested he might run for reelection again this year himself despite age and failing health. For a long time there was really no viable alternative, but now the former head of the IAEA Muhammad al Baradei has emerged as a spokesman for change and has forged an informal alliance with the country's largest opposition movement, the Muslim Brotherhood. Even before Tunis erupted, smart experts were suggesting scenarios in which change could come to Egypt.

Behind the scenes, power in Egypt remains with the army and secret police as it has since Gamal abd al Nasir seized power from a decrepit monarchy more than a half century ago. After Sadat's assassination—and in the face of Zawahiri's challenge—Mubarak vastly expanded the size and power of the mukhabarat, or secret police, and the Ministry of the Interior. The internal security police force has one and half million men under its command, four times the size of the regular army, with a budget of one and a half billion. As any tourist knows the police are everywhere. Every Egyptian knows an informant is everywhere, too. Estimates suggest 80,000 political prisoners are in jail. While the population has doubled since Sadat died, the number of prisons has quadrupled.

Mubarak has relied for decades on his secret police Chief Omar Suleiman, 75, to keep order and maintain control. Suleiman is an accomplished counterterrorist fighter well known in Western capitals and highly respected by intelligence services around the world. He has often been Mubarak's go-to political operative, handling delicate negotiations like dealing with Hamas in Gaza.

Mubarak and Suleiman have doubtless been rattled by what they have watched on al Jazirah television coming from Tunis. The joke in Cairo this weekend was whether Ben Ali's plane would stop in Cairo to pick up Mubarak. But Egyptians have been making jokes about Mubarak and his longevity for years now—and he is still there.

The stakes are enormous for America in Egypt. Transit through the Suez Canal is vital to our navy and our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The peace Sadat made with Israel is vital to Jerusalem, which every Israeli leader knows. A stable pro-Western Egypt has been the bed rock of our Middle East policy since Henry Kissinger. U.S. assistance—both economic and military—has averaged about $2 billion a year since 1979.

Barack Obama's challenge in Egypt will be to avoid tying America to Mubarak and trying to hold back the winds of change that are coming while not destabilizing a critical ally. The United States has a poor track record of pulling off that difficult balance. In Pakistan, George Bush hung by his man Pervez Musharraf far too long. The result is that Pakistanis hate America.

What has just happened in Tunisia is a revolution in Arab politics. No one knows now if it will be a one-off or the beginning of a trend. For President Obama and Secretary Hillary Clinton, the region just got a whole lot more complicated.

Bruce Riedel, a former long-time CIA officer, is a senior fellow in the Saban Center at the Brookings Institution. At Obama's request, he chaired the strategic review of policy toward Afghanistan and Pakistan in 2009. He's also the author of The Search for Al Qaeda: Its Leadership, Ideology and Future

Like The Daily Beast on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for updates all day long.

For inquiries, please contact The Daily Beast at editorial@thedailybeast.com.

>via: http://www.thedailybeast.com/blogs-and-stories/2011-01-15/tunisian-revolution...

__________________________

TANGLED WEB

Tunisia: Can We Please Stop Talking About 'Twitter Revolutions'?

About This Blog

Luke Allnutt

Luke Allnutt

An Assassination’s Long Shadow

By ADAM HOCHSCHILD

Published: January 16, 2011

TODAY, millions of people on another continent are observing the 50th anniversary of an event few Americans remember, the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. A slight, goateed man with black, half-framed glasses, the 35-year-old Lumumba was the first democratically chosen leader of the vast country, nearly as large as the United States east of the Mississippi, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This treasure house of natural resources had been a colony of Belgium, which for decades had made no plans for independence. But after clashes with Congolese nationalists, the Belgians hastily arranged the first national election in 1960, and in June of that year King Baudouin arrived to formally give the territory its freedom.

“It is now up to you, gentlemen,” he arrogantly told Congolese dignitaries, “to show that you are worthy of our confidence.”

The Belgians, and their European and American fellow investors, expected to continue collecting profits from Congo’s factories, plantations and lucrative mines, which produced diamonds, gold, uranium, copper and more. But they had not planned on Lumumba.

A dramatic, angry speech he gave in reply to Baudouin brought Congolese legislators to their feet cheering, left the king startled and frowning and caught the world’s attention. Lumumba spoke forcefully of the violence and humiliations of colonialism, from the ruthless theft of African land to the way that French-speaking colonists talked to Africans as adults do to children, using the familiar “tu” instead of the formal “vous.” Political independence was not enough, he said; Africans had to also benefit from the great wealth in their soil.

With no experience of self-rule and an empty treasury, his huge country was soon in turmoil. After failing to get aid from the United States, Lumumba declared he would turn to the Soviet Union. Thousands of Belgian officials who lingered on did their best to sabotage things: their code word for Lumumba in military radio transmissions was “Satan.” Shortly after he took office as prime minister, the C.I.A., with White House approval, ordered his assassination and dispatched an undercover agent with poison.

The would-be poisoners could not get close enough to Lumumba to do the job, so instead the United States and Belgium covertly funneled cash and aid to rival politicians who seized power and arrested the prime minister. Fearful of revolt by Lumumba’s supporters if he died in their hands, the new Congolese leaders ordered him flown to the copper-rich Katanga region in the country’s south, whose secession Belgium had just helped orchestrate. There, on Jan. 17, 1961, after being beaten and tortured, he was shot. It was a chilling moment that set off street demonstrations in many countries.

As a college student traveling through Africa on summer break, I was in Léopoldville (today’s Kinshasa), Congo’s capital, for a few days some six months after Lumumba’s murder. There was an air of tension and gloom in the city, jeeps full of soldiers were on patrol, and the streets quickly emptied at night. Above all, I remember the triumphant, macho satisfaction with which two young American Embassy officials — much later identified as C.I.A. men — talked with me over drinks about the death of someone they regarded not as an elected leader but as an upstart enemy of the United States.

Some weeks before his death, Lumumba had briefly escaped from house arrest and, with a small group of supporters, tried to flee to the eastern Congo, where a counter-government of his sympathizers had formed. The travelers had to traverse the Sankuru River, after which friendly territory began. Lumumba and several companions crossed the river in a dugout canoe to commandeer a ferry to go back and fetch the rest of the group, including his wife and son.

But by the time they returned to the other bank, government troops pursuing them had arrived. According to one survivor, Lumumba’s famous eloquence almost persuaded the soldiers to let them go. Events like this are often burnished in retrospect, but however the encounter happened, Lumumba seems to have risked his life to try to rescue the others, and the episode has found its way into film and fiction.

His legend has only become deeper because there is painful newsreel footage of him in captivity, soon after this moment, bound tightly with rope and trying to retain his dignity while being roughed up by his guards.

Patrice Lumumba had only a few short months in office and we have no way of knowing what would have happened had he lived. Would he have stuck to his ideals or, like too many African independence leaders, abandoned them for the temptations of wealth and power? In any event, leading his nation to the full economic autonomy he dreamed of would have been an almost impossible task. The Western governments and corporations arrayed against him were too powerful, and the resources in his control too weak: at independence his new country had fewer than three dozen university graduates among a black population of more than 15 million, and only three of some 5,000 senior positions in the civil service were filled by Congolese.

A half-century later, we should surely look back on the death of Lumumba with shame, for we helped install the men who deposed and killed him. In the scholarly journal Intelligence and National Security, Stephen R. Weissman, a former staff director of the House Subcommittee on Africa, recently pointed out that Lumumba’s violent end foreshadowed today’s American practice of “extraordinary rendition.” The Congolese politicians who planned Lumumba’s murder checked all their major moves with their Belgian and American backers, and the local C.I.A. station chief made no objection when they told him they were going to turn Lumumba over — render him, in today’s parlance — to the breakaway government of Katanga, which, everyone knew, could be counted on to kill him.

Still more fateful was what was to come. Four years later, one of Lumumba’s captors, an army officer named Joseph Mobutu, again with enthusiastic American support, staged a coup and began a disastrous, 32-year dictatorship. Just as geopolitics and a thirst for oil have today brought us unsavory allies like Saudi Arabia, so the cold war and a similar lust for natural resources did then. Mobutu was showered with more than $1 billion in American aid and enthusiastically welcomed to the White House by a succession of presidents; George H. W. Bush called him “one of our most valued friends.”

This valued friend bled his country dry, amassed a fortune estimated at $4 billion, jetted the world by rented Concorde and bought himself an array of grand villas in Europe and multiple palaces and a yacht at home. He let public services shrivel to nothing and roads and railways be swallowed by the rain forest. By 1997, when he was overthrown and died, his country was in a state of wreckage from which it has not yet recovered.

Since that time the fatal combination of enormous natural riches and the dysfunctional government Mobutu left has ignited a long, multisided war that has killed huge numbers of Congolese or forced them from their homes. Many factors cause a war, of course, especially one as bewilderingly complex as this one. But when visiting eastern Congo some months ago, I could not help but think that one thread leading to the human suffering I saw begins with the assassination of Lumumba.

We will never know the full death toll of the current conflict, but many believe it to be in the millions. Some of that blood is on our hands. Both ordering the murders of apparent enemies and then embracing their enemies as “valued friends” come with profound, long-term consequences — a lesson worth pondering on this anniversary.