"There Is No War on Terrorism"

Omid Memarian interviews author REESE ERLICH

SAN FRANCISCO, California, Nov 10, 2010 (IPS) - "The U.S. intentionally confuses al Qaeda with other groups around the world fighting for their independence or liberation, but it's [just] a convenient way to whip up support and get people very afraid," says author and journalist and Reese Erlich."There is no war on terrorism," he tells IPS.

Based on original research and firsthand interviews, Erlich's new book "Conversations with Terrorists" draws fresh portraits of six controversial leaders: Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, Hamas top leader Khaled Meshal, Israeli politician Geula Cohen, Iranian Revolutionary Guard founder Mohsen Sazargara, Hezbollah spiritual advisor Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Fadlallah, and former Afghan Radio and Television Ministry head Malamo Nazamy.

"Some of them I had already interviewed prior to coming up with the book idea. For example, Bashar Al-Assad, Khaled Meshal," says Erlich. "They are very widely accused of being either terrorists or state sponsors of terrorism in the United States."

Critiquing these responses and synthesising a wide range of material, Erlich, the co-author of "Target Iraq" (2003) and "Iran Agenda" (2007), shows that "yesterday's terrorist is today's national leader, and that today's freedom fighter may become tomorrow's terrorist."

Excerpts from the interview with IPS correspondent Omid Memarian follow.

Q: What can your readers learn from interviews with those who are being accused of being a terrorist or supporting them?

A: The theme of the book is to get people to look at who is accused of being a terrorist or might be considered being a terrorist, and what do they really stand for and what's really going on in their countries.

Q: In one of the chapters, you say that Ayatollah Mohammad Fadlallah is a "CIA victim". What do you mean by that?

A: Well, the U.S. was absolutely convinced that Fadlallah was the mastermind of the Marine Corps [barracks] bombing in Beirut [in 1983]. They hired a Saudi and Lebanese agent to kill him. And this is all revealed in Bob Woodward's book called "Veil".

We confirmed it with Fadlallah in the interview. It's a very well-documented case that was reported at the time. In 1985, an agent working for the CIA blew up an apartment building where Ayatollah Fadlallah lived. It killed 80 civilians but he was out of the building at the time.

Ironically, later it was shown Fadlallah had nothing to do with the bombing actually. That was confirmed to me by Bob Baer [a former CIA operative in the Middle East], who was in Beirut at the time and who was investigating who was responsible. It's a serious warning that every time you hear in the U.S. press that this militant or this terrorist has been killed, keep a sceptical attitude.

Q: In one chapter you interview Mohsen Sazegara, a former member of Iran's Revolutionary Guards. What's your take on this military organisation?

A: There is no question that the Iranian government has engaged in terrorist tactics. For example, they assassinated some Kurdish leaders of KDP in Germany; that is a classic terrorist attack outside its borders.

I make a distinction between that and a legitimate group that is fighting for independence of their country or liberation of some form of occupation. If they are supporting groups inside Iraq or in Afghanistan that doesn't automatically qualify for calling them terrorist, depending on what they are doing.

Q: How about Hamas and Hezbollah?

A: I spent some time with both of those groups. Politically, I strongly disagree with them and make it clear that they've done some horrific things and if I were Lebanese or Palestinian I would not vote for them in the elections, I would vote for other people that want to see progressive political development in both countries.

But they are also legitimate political forces; they win significant numbers of seats. Hezbollah is a part of the ruling coalition in Lebanon today. Hamas actually won the Palestinian elections, free and fair. So to simply vilify them as terrorists doesn't do any good. They have to be a part of the political negotiating process.

Q: If a legitimate political group gets involved in killing random people, does it qualify them to be named as a terrorist organisation?

A: Both Hamas and Hezbollah have used terrorists' tactics, no question about it. The Israeli government has used terrorist tactics against Lebanese and Palestinians; I think there is no doubt about that.

But Hamas and Hezbollah are very different than al Qaeda. [The latter] has a borderless campaign that they want to carry out and they are not part of any national liberation movement and they put terrorism at the core of their beliefs and tactics. That's not the case for Hezbollah and Hamas. And the U.S. knows it, actually.

Q: What is your assessment of the Taliban in Afghanistan, where you interviewed the former Taliban leader, Malamo Nazamy?

A: Nezamy saw the Taliban as a legitimate liberation group that was bringing stability, Islamic law and justice to Afghanistan. He certainly wouldn't consider himself a terrorist. He was the head of Afghan radio and TV and he refused the demand of other Taliban leaders to destroy the country's TV archives and he is very well known for that.

Today, he has many of the same views about Islam, the ruling government and attitudes towards women and so on. But he is willing to allow the U.S. and the U.S. troops for some time until negotiations can take place and that seems to be enough to make him currently an ally of [President Hamid] Karzai and the U.S.

(END)

Cholera rages in rural Haiti, overwhelming clinics

11:07 AM on 12/03/2010

In this photo taken Monday Nov. 22, 2010, a woman with cholera symptoms waits for treatment at a public hospital in Limbe village near Cap Haitian, Haiti. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

BEN FOX,Associated Press

LIMBE, Haiti (AP) -- A gray-haired woman, her eyes sunken and unfocused from dehydration, stumbles up a dirt path slumped on the shoulder of a young man, heading to a rural clinic so overcrowded that plastic tarps have been strung up outside to shade dozens who can't fit inside.

On the path to the clinic, another cholera victim lies dazed, her head bleeding because she couldn't stay atop the motorcycle taxi that carried her along the twisting country roads to the treatment center on the front line of Haiti's sudden battle with cholera.

Nearby, a 16-month-old girl wails as a nurse prods her with a needle, trying to find a vein for the intravenous fluids she needs to save her life.

Many feared Haiti's growing epidemic would overwhelm a capital teeming with more than 1 million people left homeless by January's earthquake. But, so far, it is the countryside seeing the worst of an epidemic that has killed nearly 1,900 people since erupting less than two months ago.

Rural clinics are overrun by a spectral parade of the sick, straining staff and supplies at medical outposts that could barely handle their needs before the epidemic.

At the three-room clinic near Limbe, in northern Haiti, a handful of doctors and nurses are treating 120 people packed into three rooms.

WATCH THIS MSNBC REPORT ON THE CHOLERA OUTBREAK IN HAITI

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

"It's really attacking us," Guy Valcoure, grandfather of the 16-month-old, says of the cholera. He piled on the back of a motorcycle with the baby and her mother to make a 40-minute ride in pre-dawn gloom to reach the clinic.

Holding a plastic cup in case his granddaughter gains enough strength to drink some water, Valcoure watches anxiously as a nurse tries without success to find a vein to give her intravenous fluids. Eventually, a doctor manages to get an IV into the baby's foot. "She's going to be OK," the nurse tells Valcoure.

Not everyone is so fortunate. It was too late to save an old woman carried to the clinic on a door over the weekend, says Dr. Benson Sergiles, a doctor from Cap-Haitien on loan to the clinic. "It's getting worse by the day," he says, his eyes bleary from being up all night.

And experts say the disease has not yet reached its peak.

The Health Ministry says there have been more than 80,000 cases since cholera was first detected in late October and the Pan-American Health Organization projects it could sicken 400,000 people within a year.

A makeshift clinic run by the aid group Doctors Without Borders in Cap-Haitien is seeing 250 patients a day and expects two or three times as many in coming weeks, said Dr. Esther Sterk, a physician from the Netherlands in charge of the treatment center in a crowded gymnasium.

The cases are also rising further into the countryside, as at the little clinic near Limbe.

"I don't think we're anywhere near the end of this," said Dr. John Jensen, a Canadian doctor volunteering with his wife, a nurse, for nearly a month at the clinic about 12 miles (20 kilometers) west of Cap-Haitien.

Fear over the spread of cholera even triggered a violent witch-hunt in the remote southwestern Grand Anse region, where locals have killed at least 12 neighbors on suspicions they used "black magic" to infect people, national police spokesman Frantz Lerebours said Thursday.

Cholera made its first appearance on record in Haiti near the central town of Mirebalais. From there it spread north through the Artibonite region. It has sickened thousands in the capital, but it is the vast rural population that is most vulnerable because cholera is spread by bacteria in contaminated water, and poor rural people often have no access to clean water and no clinics nearby.

"Most Haitians live in rural areas and most don't have latrines," said Dr. Louise Ivers of the medical aid group Partners in Health. "Most people have to do their business in a hole in the back garden and drink water from an unprotected source."

It is these people who have the fewest options when they get sick. "Why do you die from cholera? Because you don't have access to health care," Ivers said.

A hospital in the central Haitian city of Maissade has just two physicians to care for a population of 60,000. That center along had treated 350 cholera patients as of last week, said Dr. Tim Rindlisbacher of Toronto, Canada, who recently worked there as a volunteer with the Canadian aid group Humanity First.

He said he believes many more never got treatment.

"It is easy to miss it in the rural areas," Rindlisbacher said. "There's a lot of people who never make it to a hospital, never make it to a doctor and there's no way of tracking those people."

In much of the countryside, public transportation is rare. The nearest doctor or nurse could be a trek of many hours through the mountains. Even in the cities, ambulances don't exist and cholera patients usually travel by taxi or collective transport.

Associated Press journalists this week came upon four men carrying a 14-year-old boy on a stretcher along a dirt road, his mother trudging alongside. They had been walking four hours from their village to the town of Grand Riu Du Nord, in mountains about 16 miles (25 kilometers) south of Cap-Haitien to reach a clinic staffed by Cuban doctors, who treated the boy.

A maddening fact about cholera, which rapidly drains the bodily fluids from its victims, is that it is easy to treat and most people survive if they get medical attention. Doctors Without Borders says the disease has a mortality rate of less than 1.5 percent among people who reach the more than two dozen treatment centers it operates around Haiti.

Yet no one knows how many are dying uncounted and alone out in the countryside.

One small village visited by Guytho Alphonse, a public health promoter for the aid group Oxfam, is a three-hour walk from the nearest medical clinic. He said villagers told him that an entire family of six had died of the disease. His visit was meant to prevent such tragedies: he was distributing oral rehydration mixture and chlorine for treating wells.

Dr. Thony Michlet Voltaire, who runs a hospital in the town of Sante Borgne, about 40 miles (65 kilometers) from Cap-Haitien, said he was getting 40 patients a day. He said seven people had arrived in such bad shape over the past week that they could not be saved.

"A lot of people are dying at home because they can't make it to us," said Voltaire, who said his clinic, the Alliance Sante Borgne, was in dire need of medicine, volunteers and such basic supplies as clean bed sheets.

Aid groups and international organizations such as the United Nations are working on campaigns to confront the outbreak, but Ivers and others said it will take an army of health workers to stop cholera's spread.

"Let me put it this way: We have 3,000 community health workers and we are hiring more ... as many as we can," she said.

Copyright 2010 The Associated Press.

Several thousand demonstrators marched demanding a re-run, and accusing the current president of trying to rig the vote in favour of his candidate.

Al Jazeera's Sebastian Walker reports from the capital.

Remember When? A Great Day in Hip-Hop

Nelson George's amazing documentary of "A Great Day in Hip-Hop"--hip-hop's response to the legendary photo shoot "A Great Day in Harlem" (1958) which featured Jazz artists. Like the photo that inspired it, "A Great Day in Hip-Hop" lacked gender balance; Marian McPhartland, Maxine Sullivan and Mary Lou Williams were the only women in the 1958 shot. Given the money in Hip-hop wonder if such a shoot could even happen again given the reality of publicists and corporate interests.

Nelson George's amazing documentary of "A Great Day in Hip-Hop"--hip-hop's response to the legendary photo shoot "A Great Day in Harlem" (1958) which featured Jazz artists. Like the photo that inspired it, "A Great Day in Hip-Hop" lacked gender balance; Marian McPhartland, Maxine Sullivan and Mary Lou Williams were the only women in the 1958 shot. Given the money in Hip-hop wonder if such a shoot could even happen again given the reality of publicists and corporate interests.

Dec2010I was piddling around and ran across this footage of one of my all time favorite Civil Rights/Black Power Activist Stokley Carmichael. The speech entiltled “We Ain’t Goin’” is a racially charged one with colorful language where Carmichael talks about Malcom X, Robert Kennedy, Black Power, and the nashville riots at Tougaloo college in 1967. You can feel the focused anger chaneled by Stokley how America being on the brink of implodsion due to racial unrest, had affected young Stokley and everyone in the audience for that matter. The 1960’s will forever be a decade to remember!

Stokely Carmichael, was a Trinidadian-American black activist active in the 1960s American Civil Rights Movement. He rose to prominence first as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) and later as the “Honorary Prime Minister” of the Black Panther Party. Initially an integrationist, Carmichael later became affiliated with black nationalist and Pan-Africanist movements. He popularized the term “Black Power”. Carmichael was Born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, Stokely Carmichael moved to Harlem, New York City in 1952 at age eleven to rejoin his parents, who had left him with his grandmother and two aunts to emigrate when he was two. He attended the elite Tranquility School in Trinidad until his parents were able to send for him.

He attended the Bronx High School of Science, a specialized public high school for gifted students with a rigorous entrance exam, from which he graduated in 1960. His experience with the intellectual riches of the high school convinced him to drop his friends from the Dukes gang.

In 1960, Carmichael went on to attend Howard University, a historically-black school in Washington, D.C., rejecting scholarship offers from several white universities. At Howard his professors included Sterling Brown, Nathan Hare and Toni Morrison. His apartment on Euclid Street was a gathering place for his activist classmates. He graduated with a degree in philosophy in 1964.He joined the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), the Howard campus affiliate of SNCC. He was inspired by the sit-ins to become more active in the Civil Rights Movement. In his first year at the university, he participated in the Freedom Rides of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and was frequently arrested, spending time in jail. In 1961, he served 49 days at the infamous Parchman Farm in Sunflower County, Mississippi. He was arrested many times for his activism. He lost count of his many arrests, sometimes giving the estimate of at least 29 or 32, and telling the Washington Post in 1998 he believed the total number was fewer than 36.

HAYDEN CARRUTH POETRY PRIZE

An Annual Poetry Contest

One first place winner receives $1000 and publication in Tygerburning Literary Journal, Issue #2, Spring 2011! Two honorable mentions receive $100 and publication.

The 2011 judge: Brian Henry*

When is the deadline?

The postmark deadline is December 15th, 2010What are the guidelines?

• $20 entry fee. Make checks payable to “Marick Press”

• Entries must be postmarked by December 15th

• Submit up to three poems, not to exceed six pages.

• Poems must be original, written in English, and previously unpublished

• Your name or address should not appear anywhere on the poems.

• Your name or address should appear only on the cover letter.

• You may submit via electronically or by snail mail.

• If you mail your entry, enclose an index card with poem titles, your name, address, phone number, and email address

• If you mail your entry, enclose an SASE for notification of winners

• You may also enclose a postage-paid postcard for acknowledgement of entry (if you’d like)

• Entries must be typed, and on one side of the paper only

• If using the mail, use a paper clip or send unbound—no staples or binding, please

• Once submitted, entries cannot be altered

• No translations please

• Multiple entries allowed—each entry must include a separate entry fee

• No entries will be returned

• Email jgens@nec.edu for information or questionsTo submit electronically, please submit only one file as a word attachment, with up to three poems. Email to jgens@nec.edu

To submit via the mail, send to Tygerburning Literary Journal, New England College, MFA Program in Poetry, 98 Bridge Street, Henniker, NH 03242. Include a check for $20.00 payable to “Marick Press” or pay using a credit card on PayPal on Marick Press Website under Hayden Carruth Poetry Prize.

*No former or current students, colleagues or friends of the judge may enter the contest. Tygerburning Literary Journal adheres to the principles laid out in the Contest Code of Ethics adopted by the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP).

The Inaugural OCM Bocas Prize opens for entry on Monday 8 November 2010

The OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature is an annual award for literary books by Caribbean writers. Books are judged in three categories: poetry, fiction — both novels and collections of short stories; and literary non-fiction — including books of essays, biography and autobiography, history, current affairs, travel, and

other genres, which demonstrate literary qualities and use literary techniques,

regardless of subject matter. (Textbooks, technical books, coffee-table books,

specialist publications and reference works are not eligible.)• To be eligible for entry for the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature 2011, a book must:

1. Have been first published in the calendar year 2010 (1 January to 31 December);

2. Have been written by a single author who is either a Caribbean citizen or was born

in the Caribbean, regardless of current place of residence;

3. Have been written by an author who is living on 31 December, 2010;

4. Have been written and first published in English originally (i.e translations are not eligible).• Books must be entered by their publishers.

• There is no requirement for publishers to be located in the Caribbean.

• Each publisher may enter a maximum of five books per category (poetry, fiction, nonfiction).

A book may be entered in only one category. Publishers must get authorsʼ consent for entry.

• Self-published books may be accepted at the discretion of the judging panels.----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2010 Anderbo Poetry Prize

For up to six unpublished poems

Guidelines: http://www.anderbo.com/anderbo1/anderprize2010.htmlWinner receives:

$500 cash

Publication on anderbo.comClosing date 15th December 2010

Winter Fiction Contest

Winter Fiction Contest

Judge: Caitlin Horrocks

Submission Deadline: December 15, 2010

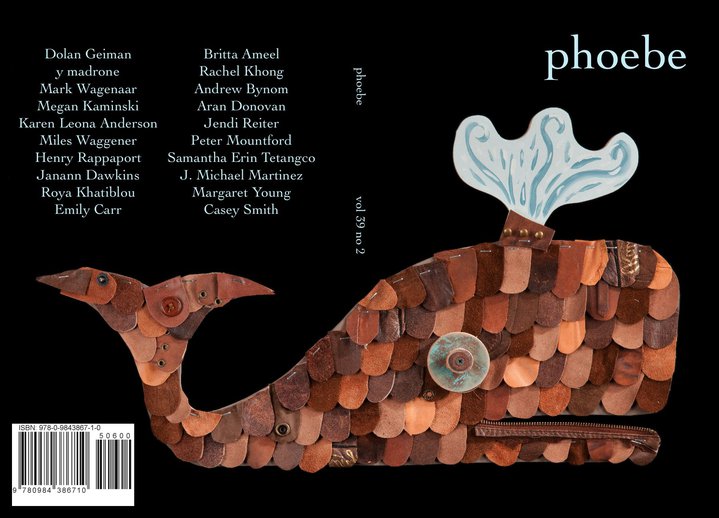

Entry Fee: $15Phoebe welcomes submissions to our 2010 Winter Fiction Contest. The author of the winning story will receive $1,000 and publication in the fall 2011 issue of Phoebe.

Contest entries should include one story of up to 7,500 words. Novel excerpts will not be considered. All entries should include a cover letter with the submission’s title and author contact information (name, mailing address, telephone number, and email address). Your name and contact information must not appear anywhere else on the story. You may submit multiple entries, but the entry fee must be paid for each story.

Mail entries to:

Winter Fiction Contest

Phoebe 2C5

George Mason University

4400 University Drive

Fairfax, VA 22030Please enclose the $15 entry fee (check or money order payable to Phoebe/GMU), and a SASE for contest results. Manuscripts will not be returned. Contest finalists will receive a copy of the fall 2011 issue. Contest entries postmarked after December 15th, 2010, will not be considered.

Thank you for your interest in Phoebe. We look forward to reading your best work!

One Response to Winter Fiction Contest

Eugene Robinson works at the Washington Post where he has served as a foreign editor, an associate editor, a columnist and the London bureau chief.

The 'Splintering' Of America's Black Population

Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America

By Eugene Robinson

Hardcover, 272 pages

Doubleday

List Price: $24.95

December 1, 2010"You can no longer talk about what black America thinks or feels," writes Eugene Robinson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post columnist, in a new book about the increasing disconnect between America's African-American communities.

In Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America, Robinson argues that America's African-American population can now be divided into four distinct groups: the abandoned poor; immigrants and people of mixed race; the mainstream middle class; and the small but powerful elite. He describes how each group has a different 'black experience' and largely remains detached from the others.

Robinson tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross that generational changes have also changed what it means to be African-American, using his own family as an example. He grew up in the Jim Crow South, while his sons grew up in a predominantly white, middle-class neighborhood. His father, who was born in rural Georgia in 1916, served in a segregated Army during World War II.

"If you look at those three generations, you see how much has changed," he says. "My father grew up at a time when basic fundamental civil rights battles were being fought. By that's totally different from the time I reached adulthood, when those rights were guaranteed, and totally different from the world in which my kids grew up."

On election night in 2008, Robinson was working as an analyst on-air for MSNBC when he momentarily left the set to call his parents. (His father, who was 92 at the time, has since died.)

"It was a night I'll never forget," he said. "I got to call and tell them that they had lived to see the election of the first African-American president and then spent several days thinking about that, thinking about the fact that [my father's] life had spanned such a period. The world in which he was born and the world in which he died were two different worlds."

'Disintegration' Of America's Black Neighborhoods

October 5, 2010

Marjory Collins/Library of Congress Prints & Photographs DivisionIn 1942, Washington, D.C.'s U Street neighborhood was a cultural center for the city's African-American community. Today, gentrification has pushed many longtime black residents out.

October 5, 2010Writer Eugene Robinson grew up in a segregated world. His hometown of Orangeburg, S.C., had a black side of town and a white side of town; a black high school and a white high school; and "two separate and unequal school systems," he tells NPR's Steve Inskeep.

But things are different now. Just look at the nation's capital — home to the first black U.S. president, a large black middle class and many African-Americans who still live in extreme poverty.

Robinson details the splintering of African-American communities and neighborhoods in his new book, Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America.

His story starts in America's historically black neighborhoods, where segregation brought people of different economic classes together. Robinson says that began to change during the civil rights era.

"People who had the means and had the education started moving out of what had been the historic black neighborhoods," Robinson explains.

Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America

By Eugene Robinson

Hardcover, 272 pages

Doubleday

List Price: $24.95

He cites Washington, D.C.'s Shaw neighborhood as a prime example of this because of how Shaw was home to a vibrant black community and a thriving entertainment scene in the 1930s through the 1950s. By the '70s, Shaw had become a desolate, drug-ridden area.

"In city after city, African-American neighborhoods that …once had been vibrant and in a sense whole — disintegrated," Robinson says.

He attributes that change to African-Americans taking advantage of new opportunities, resulting in a more economically segregated community.

"There have always been class distinctions in the black community," Robinson says, "but what I believe we've seen is an increasing distance between two large groups, which I identify as the Mainstream and the Abandoned."

Robinson says that while a "fairly slim majority" of African-Americans entered the middle class, a large portion of the community never climbed the ladder. It's getting harder and harder to catch up, he says, "because so many rungs of that ladder are now missing."

So as formerly segregated neighborhoods begin to gentrify; rents increase and longtime residents get pushed out.

"What happens to this group that I call the Abandoned is that they get shoved around — increasingly out into the inner suburbs — and end up almost out of sight, out of mind," Robinson says.

Of course, that's not to say that life was better before the civil rights movement. Robinson says Americans can't forget what life was like before integration.

"Forty-five years ago, only two out of every 100 African-American households made the present day equivalent of $100,000 a year. Now it's eight or nine," he says. "No one would turn back the clock and go back to those days."

But Robinson says opportunities for African-Americans to climb into the middle class are quickly disappearing, putting black families that did manage to make it into the middle class in a difficult position that involves a certain amount of "survivor's guilt" and plenty of frustration that efforts to help — haven't.

Julia EwanEugene Robinson works at the Washington Post where he has served as a foreign editor, an associate editor, a columnist and the London bureau chief.

"I know very few middle-class black Americans who are not involved in ... attempts to reach across the gap — through the church, through mentoring programs, by spending time reading in the schools," Robinson says. "Yet, you need something much more holistic ... and purposeful if we're frankly ever going to have the kind of impact that we need to have on the people left behind."

There's a good deal of friction between African-American communities, Robinson says, but it doesn't get talked about very much. People living in poverty "have the resentment and sourness that comes with having been left behind," he says, "the feeling that, 'Well, these people think so much of themselves, and they've moved away to their fancy places.' "

According to Robinson, there's a word for that feeling. "Sadity" is used to describe someone who is "stuck up" or who thinks he or she is better than everyone else.

"It reflects this outsized importance that is given in poor black communities to this concept of respect," Robinson says.

And if the black poor remain mired where they are right now, he says, it will be bad for everyone — that's what gives the cause a sense of urgency.

So while the changes the civil rights movement has inspired over the past 50 years have absolutely been for the good, there's still important work to do.

Excerpt: 'Disintegration'

Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America

By Eugene Robinson

Hardcover, 272 pages

Doubleday

List Price: $24.951

"BLACK AMERICA" DOESN'T LIVE HERE ANYMORE

It was one of those only-in-Washington affairs, a glittering A-list dinner in a stately mansion near Embassy Row. The hosts were one of the capital's leading power couples — the husband a wealthy attorney who famously served as consigliere and golfing partner to presidents, the wife a social doyenne who sat on all the right committees and boards. The guest list included enough bold-faced names to fill the Washington Post's Reliable Source gossip column for a solid week. Most of the furniture had been cleared away to let people circulate, but the elegant rooms were so thick with status, ego, and ambition that it was hard to move.

Officially the dinner was to honor an aging lion of American business: the retired chief executive of the world's biggest media and entertainment company. Owing to recent events, however, the distinguished mogul was eclipsed at his own party. An elegant businesswoman from Chicago — a stranger to most of the other guests — suddenly had become one of the capital's most important power brokers, and this exclusive soiree was serving as her unofficial debut in Washington society. The bold-faced names feigned nonchalance but were desperate to meet her. Eyes followed the woman's every move; ears strained to catch her every word. She pretended not to mind being stalked from room to room by eager supplicants and would-be best friends. As the evening went on, it became apparent that while the other guests were taking her measure, she was systematically taking theirs. To every beaming, glad-handing, air-kissing approach she responded with the Mona Lisa smile of a woman not to be taken lightly.

Others there that night included a well-connected lawyer who would soon be nominated to fill a key cabinet post; the chief executive of one of the nation's leading cable-television networks; the former chief executive of the mortgage industry's biggest firm; a gaggle of high-powered lawyers; a pride of investment bankers; a flight of social butterflies; and a chattering of well-known cable-television pundits, slightly hoarse and completely exhausted after spending a full year in more or less continuous yakety-yak about the presidential race. By any measure, it was a top-shelf crowd.

On any given night, of course, some gathering of the great and the good in Washington ranks above all others by virtue of exclusivity, glamour, or the number of Secret Service SUVs parked outside. What makes this one worth noting is that all the luminaries I have described are black.

The affair was held at the home of Vernon Jordan, the smooth, handsome, charismatic confidant of Democratic presidents, and his wife, Ann, an emeritus trustee of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and a reliable presence at every significant social event in town. Known for his impeccable political instincts, Jordan had made the rare mistake of backing the wrong candidate in the 2008 primaries — his friend Hillary Clinton. There are no grudges in Vernon's world, however; barely a week after the election, he was already skillfully renewing his ties with the Obama crowd.

The nominal guest of honor was Richard Parsons, the former CEO of Time Warner Inc. Months earlier, he had relinquished his corner office on Columbus Circle to tend the Tuscan vineyard that friends said was the favorite of his residences.

The woman who stole the show was Valerie Jarrett, one of Obama's best friends and most trusted advisers. A powerful figure in the Chicago business community, Jarrett was unknown in Washington until Obama made his out-of-nowhere run to capture the Democratic nomination and then the presidency. Suddenly she was the most talked-about and sought- after woman in town. Everyone understood that she would be sitting on the mother lode of the capital's rarest and most precious asset: access to the president of the United States.

Others sidling up to the buffet included Eric Holder, soon to be nominated as the nation's first black attorney general, and his wife, Sharon Malone, a prominent obstetrician; Debra Lee, the longtime chief of Black Entertainment Television and one of the most powerful women in the entertainment industry; Franklin Raines, the former CEO of Fannie Mae, a central and controversial figure in the financial crisis that had begun to roil markets around the globe; and cable-news regulars Donna Brazile and Soledad O'Brien from CNN, Juan Williams from Fox News Channel, and, well, me from MSNBC — all of us having talked so much during the long campaign that we were sick of hearing our own voices.

The glittering scene wasn't at all what most people have in mind when they talk about black America-which is one reason why so much of what people say about black America makes so little sense. The fact is that asking what something called "black America" thinks, feels, or wants makes as much sense as commissioning a new Gallup poll of the Ottoman Empire. Black America, as we knew it, is history.

***

There was a time when there were agreed-upon "black leaders," when there was a clear "black agenda," when we could talk confidently about "the state of black America"-but not anymore. Not after decades of desegregation, affirmative action, and urban decay; not after globalization decimated the working class and trickle-down economics sorted the nation into winners and losers; not after the biggest wave of black immigration from Africa and the Caribbean since slavery; not after most people ceased to notice — much less care — when a black man and a white woman walked down the street hand in hand. These are among the forces and trends that have had the unintended consequence of tearing black America to pieces.

Ever wonder why black elected officials spend so much time talking about purely symbolic "issues," like an official apology for slavery? Or why they never miss the chance to denounce a racist outburst from a rehab-bound celebrity? It's because symbolism, history, and old- fashioned racism are about the only things they can be sure their African American constituents still have in common.

Barack Obama's stunning election as the first African American president seemed to come out of nowhere, but it was the result of a transformation that has been unfolding for decades. With implications both hopeful and dispiriting, black America has undergone a process of disintegration.

Disintegration isn't something black America likes to talk about. But it's right there, documented in census data, economic reports, housing patterns, and a wealth of other evidence just begging for honest analysis. And it's right there in our daily lives, if we allow ourselves to notice. Instead of one black America, now there are four:

* a Mainstream middle-class majority with a full ownership stake in American society

* a large, Abandoned minority with less hope of escaping poverty and dysfunction than at any time since Reconstruction's crushing end

* a small Transcendent elite with such enormous wealth, power, and influence that even white folks have to genuflect

* two newly Emergent groups-individuals of mixed-race heritage and communities of recent black immigrants-that make us wonder what "black" is even supposed to mean

These four black Americas are increasingly distinct, separated by demography, geography, and psychology. They have different profiles, different mind-sets, different hopes, fears, and dreams. There are times and places where we all still come back together — on the increasingly rare occasions when we feel lumped together, defined, and threatened solely on the basis of skin color, usually involving some high-profile instance of bald-faced discrimination or injustice; and in venues like "urban" or black-oriented radio, which serves as a kind of speed-of-light grapevine. More and more, however, we lead separate lives.

And where these distinct "nations" rub against one another, there are sparks. The Mainstream tend to doubt the authenticity of the Emergent, but they're usually too polite, or too politically correct, to say so out loud. The Abandoned accuse the Emergent — the immigrant segment, at least — of moving into Abandoned neighborhoods and using the locals as mere stepping-stones. The immigrant Emergent, with their intact families and long-range mind-set, ridicule the Abandoned for being their own worst enemies. The Mainstream bemoan the plight of the Abandoned — but express their deep concern from a distance. The Transcendent, to steal the old line about Boston society, speak only to God; they are idolized by the Mainstream and the Emergent for the obstacles they have overcome, and by the Abandoned for the shiny things they own. Mainstream, Emergent, and Transcendent all lock their car doors when they drive through an Abandoned neighborhood. They think the Abandoned don't hear the disrespectful thunk of the locks; they're wrong.

Excerpted from Disintegration: The Splintering Of Black America by Eugene Robinson. Copyright 2010 by Eugene Robinson. Excerpted by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House.

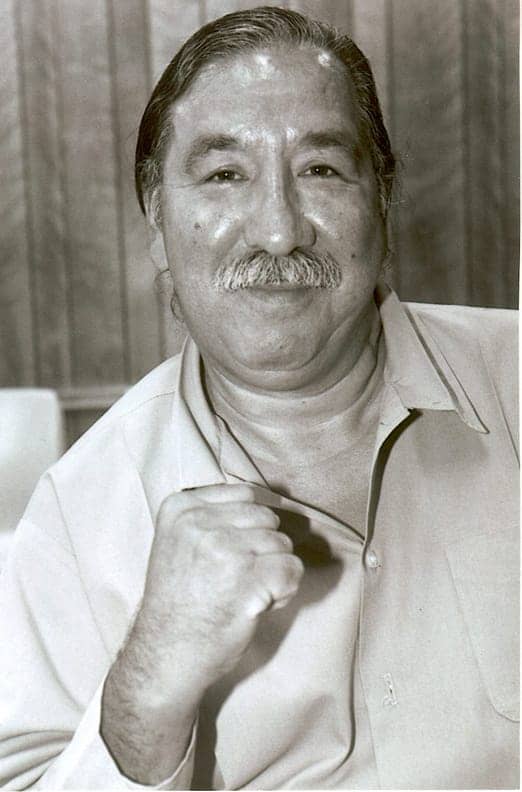

Prisoner on stolen land:

an interview wit’ Aaron about

political prisoner Leonard Peltier

November 24, 2010by Minister of Information JR

Leonard Peltier is a legendary leader of resistance against police and government oppression specifically dealing with the indigenous people of Turtle Island (Amerikkka). He has been a political prisoner of the settler-colonial government of the United States for over 30 years and is in jail for the murder of two FBI agents, although evidence proves that he is innocent. You can learn a lot about his case from the documentary, “Incident at Oglala.”

Recently his nephew Aaron released the “Free Leonard Peltier Album,” which features some of the most notable rappers on the scene today that rap for freedom. On Tuesday, Nov. 30, at 6:30 p.m., the Block Report and Aaron will be hosting a listening party for the album. Come through and learn about Leonard’s case and indigenous resistance, and come hang out as we listen to a slappin’ album. Check out Aaron in this brief interview …

M.O.I. JR: Who is Leonard Peltier? And why is he important to the international human rights movement?

Aaron: Leonard Peltier is an indigenous political prisoner who is being held captive by the U.S. government – an indigenous man who was wrongfully convicted in 1977 and has served over 30 years in federal prison despite proof of his innocence, also despite proof that he was convicted on the basis of fabricated and suppressed evidence, as well as coerced testimony.

The U.S. government fabricated a case against Leonard, which ultimately led to his conviction for the death of two FBI agents. There have been over 19 constitutional violations committed against Leonard throughout his whole case which clearly indicates his trial was in no way fair and free from prejudice. Leonard has become a symbol of indigenous resistance and a cornerstone of the human rights movement because of his commitment to the people and unwillingness to give up.

M.O.I. JR: What is the status of his case today?

Aaron: Leonard was denied parole last year and is not again eligible for decades. He has used all of his appeals and, unfortunately, when he did appeal, all of the evidence proving his innocence was not yet released to the public.

The Freedom of Information Act led to Leonard’s lawyers getting key information which proves his innocence, such as ballistic evidence which was hidden from the defense during the trial which clearly indicates that the firing pin in the murder weapon was damaged and could not be tested accurately. The truth is that they replaced the firing pin to get the results they wanted in one of many fabrications of what really happen. Leonard has become a renowned artist during his decades behind enemy lines. This is his self-portrait dressed as the warrior he is.

Leonard has become a renowned artist during his decades behind enemy lines. This is his self-portrait dressed as the warrior he is.

M.O.I. JR: Have you been in contact with him? Who is he as a person? What are some of the things that Leonard likes?

Aaron: My sister and I have written Leonard many letters over the years and he wrote back many years ago. From behind bars he has approved various elements of the “Free Peltier” album via the LPDOC (Leonard Peltier Defense Offense Committee) and he even allowed us to use his painting “Zi Warrior” for the cover of the album. Leonard is a very peaceful man and has become a mentor to many people out here in these streets and in the community from behind bars.

M.O.I. JR: Can you tell us about this cd that you just released?

Aaron: The Free Leonard Peltier Album is a gathering of members of the progressive hip hop community who are focused on the unjust incarceration of Leonard Peltier. The artists hope to raise dialogue in the community regarding the case of Leonard Peltier and expose one of the criminal justice system’s biggest abuses of justice in U.S. history.

I first conceived the album in hopes to raise awareness regarding Leonard’s plight within the community in a way they can relate to. One of my favorite lines on the album is “Human Rights organizations are trying to right this wrong but, for Peltier, the least I can do is write this song. It’s been over 30 years of tears and frustration since the brother stood up with no fear for the nation,” proclaimed by Rakaa of Dilated Peoples in his tribute to Leonard along with 2Mex in their amazing track “Right This Wrong.”

Other guests include Immortal Technique, M1 of Dead Prez, Talib Kweli, Skyzoo, Reks, T-Kash, Arievolution and iamani i. iameni, Mama Wisdom, Bicasso of the Living Legends, Eseibio, Buggin Malone, The DIme and DeeSkee.

M.O.I. JR: How can people get more info online about the case?

Aaron: For more information on the case of Leonard Peltier, please visit www.WhoIsLeonardPeltier.info and www.FreePeltierNow.org.

For more information on the “Free Leonard Peltier Album: Hip Hop’s Contribution to the Freedom Campaign,” please visit FreeLeonardAlbum.com on iTunes or FreeLeonardPeltierHipHop on cdbaby.

Email POCC Minister of Information JR, Bay View associate editor, at blockreportradio@gmail.com and visit www.blockreportradio.com.

[...] Phoebe (one of my favorites to read!!) [...]