Amílcar Cabral and Mário Pinto de Andrade

The project of writing Amilcar Cabral’s biography forced me to reconstruct the intellectual history of the times in which he lived. An archeology of ideas had to be done. This text comes then as a contribution to an intellectual biography, not Almicar’s, but of his time. And my guide is Mário Pinto de Andrade, from Angola. With “As Origens do Nacionalismo Africano” (Dom Quixote) he becomes the first nationalist and the only african in the portuguese colonial space to undertake a systemization of the formation of nationalist thought in the colonies. Mário Pinto de Andrade doesn’t consider he reached his aim of tracing the origins of african nationalism to the very start and so doesn’t find the book suitable for publishing. The document was however found in the collection of documents kept at Fundação Mário Soares, and I’m sure a full publication of the book, even unfinished, is desirable, given the scarceness of materials on this subject.

Mário de andrade starts by developing what would come to be called the first phase of african nationalism, namely, protonationalism. He suggests the practices and lists the elements of strength in nativist discourses: racial self-esteem and rescue of african values. In this nationalist first phase also take part, curiously, the future parents of Mário Pinto de Andrade’s generation, like José Cristiano Pinto de Andrade, Juvenal Cabral and Ayres do Sacramento Menezes. They exchange mail with other african diaspora organizations in Europe and America. They start newspapers and associations but do not venture beyond that. Mário Pinto de Andrade explains that this generation’s problem is the incapacity to overcome the contradiction of being both black and portuguese. So, this generation while feeling the call of their race, as Mário Pinto de Andrade puts it, when time came to choose between being either black or portuguese, chose the latter. And that choice had to be made when Salazar took power and ended a twenty year period of republican liberties and of political turmoil for the african diaspora in Lisbon, in which they had founded several organizations where that generation found their militance.

Mário Pinto de Andrade’s interest in this study has a chief interest in discourse analysis, in reading the epoch’s newspapers, the so called nativist press. But he speaks clearly when for example he takes interest in the endogenous causes of the emergence of nationalist movements. He only gives two pages to the connections between marxism and the national question. It seems then useful to delineate a genealogy of black internationalism as way to understand it’s formation. Africa’s independencies, beyond the action of africans and africans among the diaspora, take place due to a number of structural shifts. If we place the emergence of african internationalism in a broader perspective it will allow for a understanding of the paradigm changes that took place at the turn of the century.

Amílcar Cabral and Mário Pinto de Andrade

Amílcar Cabral and Mário Pinto de Andrade

Paradigm shift

Some questions arose while writing Amilcar’s biography: how did it happen that half a handful of youngsters, coming african colonies, won in such a short period the right to speak for their people? which institutions supported them? Which theoretical background legitimized their claims? Mário Pinto de Andrade is right when he perceives in this phenomena a shift regarding race consciousness. How does this shift take place? What permitted that in less than 50 years, from 1900 until 1950, when Mário Pinto de Andrade and his comrades studied in Lisbon, the perception of colored people changed so radically? Until WWI, social scientists, especially anthropologists, used without restraint words such as “savages” and “primitives” to characterize African people. However, in the thirties or forties, few would find scientific bases that would validate a given superiority of white men, except for portuguese anthropologists like Mendes Correia, from an anachronic physical anthropology department in Faculdade do Porto. And in the sixties almost the whole continent was already independent and leaded by black majority rule, with the exception of the portuguese colonies and some other countries like Namibia, colonized by South Africa. What happened in such a short time-span? What paradigm shift allowed the demise of the racial superiority principle that, according to illustrious black thinkers such as William Du Bois, was in the very foundations of the capitalist system and the reduction of people to commodity status, proved by slave trafficking and colonialism.

In 1900 Freud publishes “The interpretation of dreams”. A epistemological cut with the positivist tradition is announced. African independecies can only be understood in what they had of anticipation of an utopian future. However, it’s these utopic ideas that allow a conception of african independencies. Utopia is a big word in the 19th century, as a reaction to the reigning liberalism, but it was already present in the works of Plato, Saint Agustin and later on Thomas More, Campanella and Rosseau. However with Marx and Engels it’s character was to change. Utopia became a commitment to the necessity of a revolution. in 1848, upon the Paris revolution, Marx announces in several articles the arrival of a new humanity, walking in the ruins of an old civilization that had given commodities cult and religious status. But it is Engels that makes a break between old utopian models and a new one, that commits to the formation of new societies. In 1908, Engels writes a pamphlet of special relevance called “Socialism: Scientific and Utopic”, in which all former utopias are criticized, those from Owen and Fourier, accusing them of having their roots in religious thought, of tending to the formation of small perfect communities, or subcultures, that aren’t more than the establishment of perfect communities within imperfect organisms. to Engels, utopia had to be approached in a broader perspective, one that would include scientific socialism. Only scientific socialism would, trough revolution, allow the destruction of the capitalist system’s foundations and the creation of a society based on the advancement of the proletariat’s interests. (Horowitz, 109).

Dreams of freedom

The necessity of new societies, or of building a world upon the foundations of the old order was a project that attracted several black communities coming out of slavery. Slavery was, within this group, understood as a sub-product of capitalism. The libertary scope of the 19th century revolutions and the 1848 publication of the “communist party manifesto” becomes clear. It’s reading, in what concerns the recently emancipated black communities, was touched by several events that had changed the relation between blacks and whites or it’s perception. In 1804, a slave revolt leaded by Toussaint Louverture won over the french army and proclaimed an early independence of the world’s first black nation (Haiti). The event, with great impact in the black world, echoed old dreams of runaway slave’s failed republics, the quilombos, the most emblematic being Quilombo dos Palmares, that lasted for about a century from 1580. Palmares, founded by Zumbi, a slave allegedly coming from the Kingdom of Congo, put an utopic nation in the hearts of blacks all over the world. In these emancipatory movements religious references are found, such as exodus, that will later lead the black zionism of Marcus Garvey, but also political ones, mainly influenceddd by the communist party manifesto, or otherreferringngng to a certain african philosophy, as explained by Liberian Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832-1912) who wrote: “African cultures are naturally communist and don’t allow private property of the land. The emphasis they put on collective responsibility make crime and poverty non-existent.” (Kelly, 23)

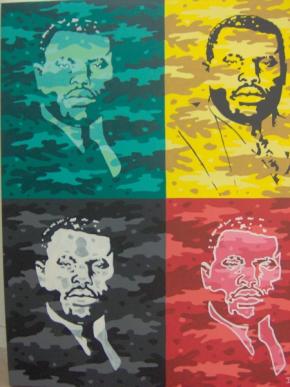

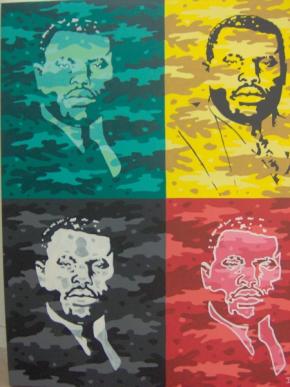

Marcus Garvey, by Ihosvanny, 2006 / Sindika Dokolo Foundation

Marcus Garvey, by Ihosvanny, 2006 / Sindika Dokolo Foundation

Marxism and surrealism

For several of the black communities of the time these dreams of freedom were born out of the hard life and labour conditions in which they had found themselves after the formal abolition of slavery. The american civil war (1861 – 64) hadn’t brought substantial changes for black people since, even if in the north some freedom was apparent, from 1876 to 1965 they lived under the Jim Crow laws that kept some political rights from the black population, following a 1857 law, Dred Scott v. Sanford, that considered all blacks as not being american citizens. It is in this context of betrayal of hopes of black americans that the expression New Negro arises, hoping for a change in minds. Taking as support the structures of print capitalism, in Benedict Anderson’s sense, using brochures, pamphlets and books to make their equals aware of their subordinate condition. And so it was created, all over the black world, United States, Caribbean, Europe and some parts of Africa, such as the Creole Africa of the angolan, the cape-verdean, the senegalese and the ganese, a sort of black brotherhood. A powerful slogan was born. The gain of political rights was dependent on the imposition of the new negro. It was a stand taken against white supremacy, that gained form in intellectual aspirations and political radicalism.

But it becomes necessary to understand the emergence of the new black man in it’s purely ontological character. The new black man wasn’t a figure you could find in Paris or the streets of Harlem. It was an aspiration; it was a goal. An utopia, a vision of the future, as one can see in the Booker T. Washington essay: “New Negro for the future”.

Capitalism being associated with slavery, blacks turned to marxism. However, until then, blacks and whites had extremely different ideas about the nature of proletarian revolution. White communists don’t consider blacks part of a struggle against capitalism. That is to say, they didn’t have any particular sensibility towards race issues. The marxism that reached Harlem, where the Harlem Renaissance movement was based – probably the most famous american modernist movement, reuniting poets such as Richard Wright, Claude McKay, Countee Cullen and Langston Hugues – had nothing to do with the marxism of white americans. These poets, all communists, exchanged letters with other communists and for several times even paid visit to the Soviet Union.

One of the main links these black american communists had was with french intellectual milieus, specially André Breton’s Surrealist Group. Surrealism had begun in the twenties trough readings and applications in the poetic field of Sigmund Freud’s work, mainly the one dedicated to the study of totemism. The idea was to create a poetry that put special emphasis on the practice of magic, spirituality and ecstasy. Surrealist pursued partly the legacy of romanticism, with the importance they gave to the exploration of the states of uncounsciousness. They wanted, however, to capture a new feeling, something primitive, that they believed was to be found n the poetry of black americans, such as Langston hughes, as Countee Cullen, and in the music that was starting a revolution: Jazz. Of black american culture, music, painting, poetry and folklore, emphasis was made on imagination, improvisation and verbal agility.

Contributions of Anthropology

This openness toward the appreciation of different cultures came certainly from anthropology, of great interest to the surrealists. At least two of their members would pursue professional careers that included ethnography, Michel Leiris, author of “Afrique Fantôme”, or Georges Bataille, who would write several books based on anthropological readings. This valuing of the cultural legacy of people considered “primitive” and “savage” walks side by side with the destruction of racial superiority myths, something that anthropology had contributed greatly to. From anthropology came the idea that there were no inferior or superior cultures, as the Columbia University Anthropology department said, founded by Franz Boas in 1902. Boas, physic by formation who became and anthropologist and worked with indians and later on with afro-americans, started the cultural relativism school. Boas’s students produced studies that displace from social sciences the myth of white man’s superiority. Or, at least, that the characteristics associated with the white man weren’t natural, but related to social and cultural contexts.

Gilberto Freyre, for example, in “Casa Grande e Sanzala”, celebrates the synthesis of black and white, crowning the mulatto and the Brazilian type par excellence. Not necessarily the biological mulatto but the cultural one. Edward Sapir, linguist, anticipates several of the work Noam Chomsky would come to produce with his universal grammatical theory. To Sapir, every language in the world was a part of a same phonetical universe, with endless possibilities. It was up to each culture the selection of sounds towards the construction of phonetical communication. Ruth Benedict, the author of the famous “Patterns of Culture”, and her student Margareth Mead contributed to the spread of Boa’s ideas beyond the academic world. Based in Boas’s and Sapir’s linguistic studies they worked cultural concepts that came from linguistics. Meaning, that like the universal system of languages, culture patterns were simply the those strokes that made up systems. But with endless possibilities. With the declaration of cultural relativism there were no longer inferiors and superiors. anthropology should, through the study of non-western peoples, contribute towards the enrichment of the western cultural pattern.

André Breton

André Breton

Surrealism

It is then within the breach of western rationality that surrealism appears, but also in a certain exotification of black people, that the birth of the surrealist movement occurs. It is not by chance that Langston Hugues starts his autobiography mentioning the roaring twenties and his trips to paris with the phrase “It was the time when the negro was in vogue”. In specific french milieus black people were indeed in vogue, as can be seen in the paintings of Pablo Picasso, and also in how often the Museu de l’Homme organized shows on black culture. Surrealism was born out of this exchange between blacks and whites. It wasn’t just a mean towards artistic subliminal experience, coming from the readings of Freud, but also a revolutionary practice in the terms proposed by Marx. To conciliate spirit and revolution is an obvious intent of a document produced, while much later, 1979, by the Chicago Surrealist Group.

One of the most interesting things about surrealism was that it was shaped by it’s interest in Africa that came via anthropology but that was also fundamental in shaping african and african diaspora political and cultural movements, through what was called “Pure Psychic Automatism”.

It wasn’t just conceptually that surrealism appeared against western rationaity but also politically, by turning it’s attention on to the “primitives”, that that later would be called the third world, meaning, places run by colonialism. It was towards a politicization of the third world that in the twenties the Paris Group was formed. They came together in 1925 to support Abd-el-Krim, leader of a revolt in Marroco against french colonialism. Several hands wrote an open letter to the ambassador in Japan, Paul Claudel, also a writer, in which they announced that “we profoundly hope that the revolutions, wars and insurrections annihilate this western civilization your excellency defends even in the east”. Three years later the paris group would produce the most militant document about the colonial question of the time, “Murderous Humanitarianism”, signed by the same, René Cravel, André Breton, Paul Éluard, Benjamin Peret, Yves Tanguy and the martinians Pierre Yoyotte and J.M. Monnerot. In this manifesto, originally published in Nancy Cunard’s anthology, Negro (1934) they stated that the humanism upon the western world was built also justified slavery, colonialism and genocide. The writers called to action: “we, surrealist, pronounce ourselves in favor of turning the imperial war in it’s chronic colonial shape into a civil war. We this way put our energies available to the revolution of the workers and to their fights, and define our attitudes in relation to the colonial problem, and then, to color issues”.

Aimé Césaire

It was maybe Aimé Césaire the one who best synthesized marxism and surrealism. His intellectual growth shows the way between surrealism and a anti-colonialist conspiration that is the genesis of the third world bloc. in 1950 Césaire writes the “Discourse on Colonialism” considered by Robin Kelley the third world movement manifesto, where, using surrealist tactics, such as free association, he creates a document that might just have announced some of the questions that would decades later occupy one of his students, Frantz Fanon. In this document all of the old topics of the surrealist stand on colonialism appeared: Dehumanization, brute force and violence.

It is then within the breach of western rationality that surrealism appears, but also in a certain exotification of black people, that the birth of the surrealist movement occurs.

Aimé Césaire

Aimé Césaire

Aimé Césaire was a full member of the Paris surrealist group, with other Martinians like Etienne Léro, René Meril, J.M. Monerot, Pierre Yoyotte and his sister Yoyotte, and founded in 1932 the newspaper “Légitime défense”, that conjugated marxism and surrealism as can be seen in the collaborations of other group members, with essays and automatic writing poems. Aimé Césaire founded, with Leopold senghor and Leon Damas, the magazine “L’Étudiant Noir”, where students from the Lisbon group participated, namely Amilcar Cabral, Mário de Andrade, Noémia de sousa, Alda Espírito Santo and Agostinho Neto.

The creation of the word Negritude is also attributed to Césaire, in his poetry book Cahier de retour au pays natal. According to Kelley Césaire’s thought was characterized by his filiation in the modernist movement, where he picked up the concept of creative freedom and the profound admiration for the ways of thought and action of the pre-colonial african societies; Of Surrealism he rescued the mind revolution strategy; and of marxism the idea of revolution of the productive forces. His philosophy and poetry mixed Negritude, Marxism and Surrealism, a synthesis that made him to enroll in the communist party in the fifties.

It is important at this point to state a difference between Césaire and the generation that preceded Mário de Andrade and Amílcar Cabral, that considered themselves black and portuguese. While the african diaspora in Lisbon was not politicized, as were most social movements in Lisbon, Césaire militated in the French communist party and wrote incendiary documents against colonialism. However, this militance was probably caused by Lenin taking power. Lenin made the racial issue, or at least, the ethnic and colonial issue, the center of communist strategy. As we have already seen, until the first world war, communists were only interested in class, turning everything into a conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Black were blacks, to use a crude language, because they were poor.

It was believed that once suppressed capitalism, racism too would end. Lenin, leading the bolsheviks that had made the coup and announced the proletariat’s dictatorship, launched the third international, putting special attention on the colonial issue. He then wrote his “thesis on the national and colonial question”. Lenin only made the world’s problem what had been Russia’s. With the revolution and the constitution of soviet’s Russia there was now the need to solve the conflicts between the diverse groups that formed the union. The federative principle that Lenin had thought for Russia served as a model to the constitution of a world order once abolished the capitalist system. Meaning, the resolution of class contradictions was a condition for the admission of republics on the soviet space.

At the same time, the formation of a supra-national organization once solved the contradiction between the bourgeoisie and proletariat, or capitalist and oppressed, was needed. Hence probably the support the soviet union gave to the revolutionary movements. On the other side, Lenin applies here some of the principles of the communist manifest: “Workers do not have a nation. You can’t take from them what they haven’t got. Since each nation’s proletariat must, in first place, conquer political power, rise as the ruling class of the nation, become itself the nation” or its inversion “if you suppress exploitation of man by man you suppress the exploitation of one nation by another”

Race issues

It was within this debate that the race issue arrived to the United States and to the politicized poets circle. On the fourth congress of the third international, or the Cominternas it would be known, in november 1922, Claude McKay was present and, in the company of other black delegates, was received as a celebrity. In his address he criticized the american communist party and the labour movement of being racist, and stated that if the left didn’t challenge white supremacy the ruling classes would use blacks to mine the advancements of the revolutionary movement. (Kelly, 47). The participants in the symposium were so impressed that a Black Commission was formed, to whom resources were given to recruit black cadre and support black liberation at a global scale. But that demanded a revolutionary interpretation of communism’s mains problem, Class war. While racism existed no class consciousness could exist. Blacks, such as russian ethnics, were an oppressed race and as all oppressed races had a right to self-determination. Lenin makes a link between community and culture that would be fundamental to african independence aspirations: autonomous cultures had a right to political representation.

The black diaspora quickly understood that the resolution of racial contradictions passed trough militant communism. In other words, only communism had solutions for racism. That becomes important in the writings and actions of Du Bois. In 1906, when he militated in the american socialist party and in black movements such as Niagara and NAACP, Du Bois said something that would become important, The Twentieth century would have color as it’s main problem (color here in it’s broad sense, including asiatics). In January 1919 Du Bois took part in the Paris Peace Conference, on the onset of the first world war, in which the resolution of Europe’s ethnic problems was disputed trough the concession of independence to the peoples constituted as political entities, Du Bois writes in The Crisis, the newspaper of one of the most important black associations of the time, the NAACP, that the idea of liberation had to be equally spread to Africa. And with this principle Du Bois launched the Pan African Congress, that had meetings in 1919, 1921, 1923 – with a Lisbon Session – in 1927, and that would certainly create the political and overall legal conditions, in terms of international law, to african independencies. Du Bois seemed to answer to the white communists reserves towards racial issues, when he said that europe had only postponed a continent wise revolution by the tracing of a color divide that had allowed the transfer of exploitation from the european working class to the underdeveloped races under political domination. And in this moment Du Bois breaks from the socialist party, since, like all communist and socialist groups in the United States, as in Portugal, an understanding of race as fundamental element in capitalist exploitation was yet to come.

Mário Pinto de Andrade

Mário Pinto de Andrade

Starting with the evocation of Mário de andrade’s studies I have tried to draw a genealogy of the black movement, revisiting some fundamental strokes, namely the anthropology of cultural relativism that contributed to the end of an idea of racial superiority; a black activism that rescues racial self-esteem; and an artistic movement, surrealism, that leaving behind western rationality, fuses, for the first time, art and political commitment. All these factors interact amongst themselves. It is anthropology that allows art to embrace the issues of the “primitive” and the “savage”; it’s the surrealists that transform all of that into a discourse against colonialism; and most important of all, put the question of race, in its broad sense, in the center of the communist movement issues.

Translation: Luhuna de Carvalho

___________________________________

by ANTÓNIO TOMÁS

Angolan anthropologist. He is the author of two books: "O Fazedor de Utopias: uma biografia de Amílcar Cabral" and "Poligrafia: das páginas de jornais angolanos". He is currently finalizing a Ph.D. in Anthropology at Columbia University in New York.

RADIO DIED for me two weeks ago when I finally turned off from SAfm (one of South Africa’s premier talk radio station and part of the South African Broadcasting Corporation – SABC – stable). I had been a loyal listener of this radio station for close to seven years. It was a painful death. You see like any person you speak to on this continent radio was my love. When I was at a certain age I did not need the alarm to know that I now had to dash off to school. There was the Jarzin Man on Radio Two to alert me to this: 06:45am and the Jarzin programme would kick off with the signature tune “Jarzin, J-A-R-Z-I-N”. Then of course Admire Taderera with that lovely voice would chirp, “Ndini wenyu murume wemadhora, Jarzin Man, ndinoti mangwanani akanaka” (I am your money-man, the Jarzin Man. Good morning). Radio was not just alive – you lived with it.

RADIO DIED for me two weeks ago when I finally turned off from SAfm (one of South Africa’s premier talk radio station and part of the South African Broadcasting Corporation – SABC – stable). I had been a loyal listener of this radio station for close to seven years. It was a painful death. You see like any person you speak to on this continent radio was my love. When I was at a certain age I did not need the alarm to know that I now had to dash off to school. There was the Jarzin Man on Radio Two to alert me to this: 06:45am and the Jarzin programme would kick off with the signature tune “Jarzin, J-A-R-Z-I-N”. Then of course Admire Taderera with that lovely voice would chirp, “Ndini wenyu murume wemadhora, Jarzin Man, ndinoti mangwanani akanaka” (I am your money-man, the Jarzin Man. Good morning). Radio was not just alive – you lived with it.