NEWS » JUNE 25, 2010

Certifying ‘Blood Chocolate’

Activists question the candy industry’s commitment to ending cocoa industry child labor.

Henriette Gneza holds a cocoa pod near the village of Boko, Ivory Coast, where in 2005 a group of women created an association of coffee-cocoa producers. (Photo by: ISSOUF SANOGO/AFP/Getty Images)

Eighty percent of the world’s cocoa, the main ingredient of chocolate, is produced by millions of growers in the Ivory Coast and Ghana, according to the nonprofit CorpWatch.

Conscientious consumers’ search for ethically sourced and manufactured products has expanded beyond diamonds, coffee and clothing to sweeter terrain: chocolate. After years of pressure, multinational candy companies are finally beginning to embrace the “ethical cocoa sourcing” movement—but to what degree and effect remains a matter of debate. Labor activists say manufacturers’ commitment to the seals of approval adorning chocolate bars is dubious, and the standards themselves are flawed.

Since the late 1990s, labor-rights organizations have been pressuring food companies to verify that their chocolate is not the product of child labor or slavery. Eighty percent of the world’s cocoa, the main ingredient of chocolate, is produced by millions of growers in the Ivory Coast and Ghana, according to the nonprofit CorpWatch.

In 2001, eight members of the Chocolate Manufacturers Association, including industry leaders Mars and Nestle, signed the non-binding Harkin-Engel “Cocoa Protocol” that committed the companies to eliminating the “worst of child labor” in West Africa. Participating manufacturers were supposed to have met the international agreement’s standards by 2005, but hundreds of thousands of children continue to work on cocoa plantations in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, according to a 2009 Tulane University study of the cocoa industry.

But last year, Mars and Cadbury announced their commitment to “ethical sourcing.” Mars, which makes Snickers and M&Ms and had $30 billion in global sales in 2008, has partnered with the Rainforest Alliance (RA) to ensure its entire cocoa supply—100,000 tons—is “sustainably produced” by 2020. Mars’ Galaxy candy bar, popular in the United Kingdom, began bearing the Rainforest Alliance Certified™ green seal this year. The New York-based RA’s sustainable agriculture standards forbid child labor, except when children are part of the farm owner’s family.

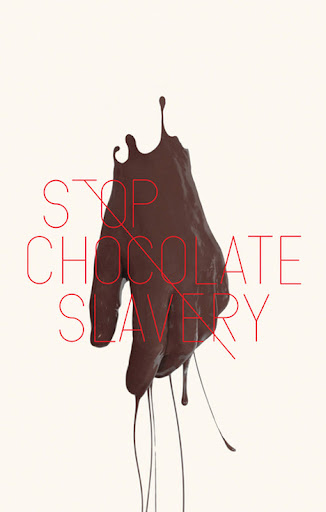

But critics say RA standards aren’t tough enough to change an industry still rife with “blood chocolate,” and are instead a cheap way to tap into the ethical consumer market without a substantial change in business practices. Kyle Scheihagen, founder of the online advocacy group Stop Chocolate Slavery, says that since 2005 most large companies have produced only a few certified products to accommodate a small consumer demand. At the same time, Scheihagen says, they make their profit by “selling bad [exploitative] products. That just seems like a cynical approach.”

Labor organizations are dissatisfied with manufacturers’ moves, because “ethical sourcing”—a phrase chocolate companies use to market their products—doesn’t guarantee the better labor practices that are part of official “fairtrade” certification, which occurs though the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations (FLO) International and its 23 member agencies. “

“Fairtrade” and RA-certified products offer the same appeal to some consumers, but their production and content standards are very different. RA products are only required to contain 30 percent “certified content”—meaning that the majority of the product does not reach the organization’s standards. “Fairtrade” products must contain 100-percent certified content, and guarantee a minimum price to producers.

RA has asked its producers to scale-up their products to 100-percent certified content, but has not established a deadline. “We didn’t want to have a 100-percent requirement and be a deterrent to large companies,” says RA spokeswoman Abby Ray. (RA’s board of directors includes an executive chairman of Pinnacle Foods and an ex-CEO of Kraft.)

“There are some fundamental problems with Alliance guidelines,” says Tim Newman, an International Labor Rights Forum (ILRF) spokesman. RA does not require unionization of workers, and several RA-certified cut-flower farms have quashed workers’ attempts to unionize, he says. (Ray says that workers on RA-certified farms have “freedom of association.”)

Newman also faults RA for not requiring workers to be paid a living wage (instead RA-certified farms can be paid a wage comparable to surrounding farms). Newman says that RA standards don’t “provide a lot of incentive for a company to scale up” to better standards. Mars and Kraft did not respond to requests for comment.

Global labor rights researcher and activist Jeff Ballinger criticizes the certification model of both RA and FLO, saying if they really want to stop longstanding abuses like forced child labor, they need to pressure local governments to enforce laws, not just check up on farms periodically. “They aren’t [bulletproof] practices by any means,” Ballinger says. “Pressuring governments is the way to go.”

Sara Peck, a spring 2010

In These Times editorial intern, is a Northwestern University student studying journalism and political science.

More information about Sara Peck

===================================

Last week I wrote about a fresh commitment from European Union members and several other countries of the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) to make the $10 billion abuse-ridden cocoa industry more sustainable and fair to workers (the U.S. was still conspicuously absent from this organization). Today comes newsthat this agreement will largely be wishful thinking until the United States, the largest consumer of cocoa, signs on to such agreements or guarantees its chocolate as Fair Trade.

Last week I wrote about a fresh commitment from European Union members and several other countries of the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) to make the $10 billion abuse-ridden cocoa industry more sustainable and fair to workers (the U.S. was still conspicuously absent from this organization). Today comes newsthat this agreement will largely be wishful thinking until the United States, the largest consumer of cocoa, signs on to such agreements or guarantees its chocolate as Fair Trade.

The U.S. ambassador to Ghana recently announced that since January, the U.S. has been importing much more cocoa than ever thanks to two new processing facilities built by ADM and Cargill, one of the top five global processors of cocoa beans. U.S. cocoa imports are expected to increase, too, as American businesses are busting down the door asking for new contracts in the impoverished country. In the past year, there's been 100-to-200 percent more requests from Americans seeking to do business in Ghana, the second-largest producer of cocoa after the Ivory Coast.

This means small farmers in Ghana, which along with the Ivory Coast produce about 60 percent of the world's chocolate, will be pushed to produce more cocoa. Unless they are protected under Fair Trade contracts, rampant exploitation and slavery of workers will most likely continue. About 3.6 million West African children work on cocoa farms, many of whom make very little to no pay while under horrific conditions, according to the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). This dire situation has led some to refer to cocoa produced in these regions as "blood chocolate." According to a January report by the International Labor Rights Forum, chocolate companies like Mars and Cargill, which process 400,000 tons of cocoa each year, "have been able to control initiatives meant to eliminate forced, child and trafficked labor in West Africa’s cocoa industry." More cocoa corporation consolidation has only further pressured farmers to keep costs low. Efforts by the U.S. government and labor rights groups have largely failed to improve conditions, according to a 2009 Tulane University study.

What have American chocolate companies like Hershey's and Mars, the world's largest chocolate manufacturers, done to help? They've established certain initiatives and their own sustainable guidelines, but after nine years of such self-defined and self-monitored (read: unregulated) initiatives, little has changed. British companies Nestle UK and Cadbury have justly adopted Fair Tradecertification for their chocolate, and deserve our applause. Sign our petition telling U.S. candy companies that they need to do the same.

Photo credit: Zapstratosphere via Flickr

Jean Stevens is a freelance journalist based in New York whose work focuses on issues relating to sustainable food.

>via: http://food.change.org/blog/view/tell_mars_cargill_and_hershey_to_stop_using_...

============================================

Cocoa farmers in West Africa – growers of the main portion of world cocoa supply – are distant actors in a weird rumble over prices, which recently hit a 33-year peak, achieving the highest prices on record since 1977. The proximate cause of the record price is speculative activity by commodities traders, especially a particular hedge fund, Armajaro of London, which recently shocked financiers by actually taking deliver of physical cocoa.

The financial drama has masked a fundamental shift in the pricing of one of Africa’s most prized outputs. Cocoa is essential in the manufacturer of chocolate and producers, who are largely clustered in the neighboring countries of Ghana and Ivory Coast, have long failed to form a cartel to drive up prices, much in the same oil producers (OPEC) do. In economic terms, cartels can make sense, rewarding owners of a relatively scarce commodity.

Common and concerted action is often required for a cartel to take hold. When governments try to form cartels – say, to fight back against traders in the world’s big cities – they must hew to the same script. In the case of Ghana and Ivory, such common action has never been possible. Since independence in 1957, Ghana’s government has closely controlled the sale of cocoa, essentially nationalizing the crop through a cocoa board that acts as a single selling agent on the international market and prices on farmers who by law must sell their crop to the government. Ivory Coast, by sharp contrast, has long permitted farmers to sell to anyone, on the open market, at any price they can fetch. The result is that farmers in Ivory Coast gain more money from their cocoa than farmers in Ghana; it also means that official production in Ivory Coast is boosted by smuggled cocoa from Ghana.

The cartel of international cocoa buyers – chiefly America’s ADM and Cargill and Zurich-based Barry Callebaut – all of three of whom exist in close cooperation with a small group of global end users, concentrated in Europe and the U.S. – benefited greatly from the schism between Ghana and Ivory Coast on cocoa policy. Lower prices were the result. For decades even, Western companies, and consumers, benefited from ultra-low prices of raw cocoa, which fueled the expansion of cheap chocolates in groceries and sweet shops.

The days of inexpensive cocoa are unlikely to return. One expert told the Financial Times on July 30 “If you consider the fundamentals, I’d tend to say prices won’t fall. There’s no fundamental reason why cocoa should become cheaper.” And that’s not because of the changing practices of commodity traders. Demand for cocoa is already high, China (largely chocolate-free today) represents a new frontier and cocoa supply is stagnant, so a re-evaluation upward of cocoa has occurred.

The benefits to African farmers should be significant over time. Unlike some other crops, new gardens can require years of planning and labor. Existing trees are subject to blight and aging and must be worked intensively to maintain yields. When I visited Ghana’s cocoa-growing region a year ago, I was struck by the prosperity of farmers I met but also the relative inflexibility of growing cocoa. Expansion of output is hard to achieve. Inputs, such as fertilizers, are expensive and are used less than they should be by non-organic growers. New trees take years to reap fruit. Field labor is surprisingly costly. Producers also fear a glut; they can benefit from stagnant production too.

Ghana’s independence leader, Nkrumah, once dreamed of setting cocoa prices in Accra and Abijan, not in London or Chicago. A producer cartel proved impossible, and cocoa farmers in West Africa suffered. Now a “market cartel” has emerged. West African cocoa farmers, and their families, should be cheering. Capitalism, so often the instrument of their oppression, is now working dramatically in their favor.

>via: http://africaworksgpz.com/2010/08/02/markets-at-long-last-deliver-for-west-af...

Last week I

Last week I