The revolution and

the emancipation

of women

— A Reflection on

Sankara’s Speech,

25 Years Later

Amber Murrey

2012-06-20, Issue 590

http://pambazuka.org/en/category/features/83074

The life and work of Thomas Sankara can be taken as a reminder of both the power and potential for human agency to enact transformation.I would like to situate my ideas within the geo-political context of the popular uprisings that continue to take place around the world as people organise against neoliberal policies of advanced capitalism and their resultant gross inequalities in wealth, health and education. Accompanying the intensifying neoliberal crises - manifested through the financial crisis, food security crisis, and struggles over land reform and landed property - is an ever expanding militarisation. The US military now has more bases and more personnel stations in more countries than ever in its history. The US Africa Command is one component of the US military’s current phase of expansion, including millions of dollars of military equipment, arms and training in African nations.

This is our contemporary moment as we approach the 25th anniversary of the assassination of Thomas Sankara.

The revolutionary transformation of the West African country Upper Volta to Burkina Faso (what is known as the August revolution of 1983) occurred during a previous neoliberal crisis, that of the 1980s African debt crisis. Sankara vehemently and publicly denounced odious debt and rallied African political leaders to do the same.

Sankara’s politics and political leadership challenged the idea that the global capitalist system cannot be undone. During four years as the president of Burkina Faso, he worked with the people to construct an emancipatory politics informed by human, social, ecological and planetary wellbeing. The people-centred revolution was a pivotal point for a shift towards new societies on the continent. We have much to learn from the Burkinabé revolution.

What distinguishes Sankara from many other revolutionary leaders was his confidence in the revolutionary capabilities of ordinary human beings. He did not see himself as a messiah or prophet, as he famously said before the United Nations General Assembly in October of 1984. It is worth quoting from Sankara at length, when before the delegation of 159 nations, he said:

‘I make no claim to lay out any doctrines here. I am neither a messiah nor a prophet. I possess no truths. My only aspiration is…to speak on behalf of my people…to speak on behalf of the “great disinherited people of the world”, those who belong to the world so ironically christened the Third World. And to state, though I may not succeed in making them understood, the reasons for our revolt’.

Furthermore, Sankara placed women’s resistance agency at the centre of the revolution. He saw women’s struggles for equal rights as a focal point of a more egalitarian politics on the continent.

Meaningful social transformation cannot endure without the active support and participation of women. While it is true that women have been deeply involved in each of the great social revolutions of human history, their support and participation has historically often gone relatively unacknowledged by movement leaders. This was the case when Russian women united to march in St. Petersburg in February of 1917, demanding bread. Similarly, French women marched to Versailles in 1789, again to demand bread. Despite significant contributions to revolutionary movements, women remained second-class citizens. Oftentimes women’s political organisations were chastised by formalised male-led revolutionary groups.

Women mobilised for freedom against colonial and neocolonial oppressions In revolutionary and social struggles across the African continent. Again, many male leaders either omitted or failed to recognise the vital nature of the work carried out by women to mobilise and maintain social movements.

Sankara was somewhat unique as a revolutionary leader - and particularly as a president - in attributing the success of the revolution to the obtainment of gender equality. Sankara said, ‘The revolution and women’s liberation go together. We do not talk of women’s emancipation as an act of charity or out of a surge of human compassion. It is a basic necessity for the revolution to triumph’.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

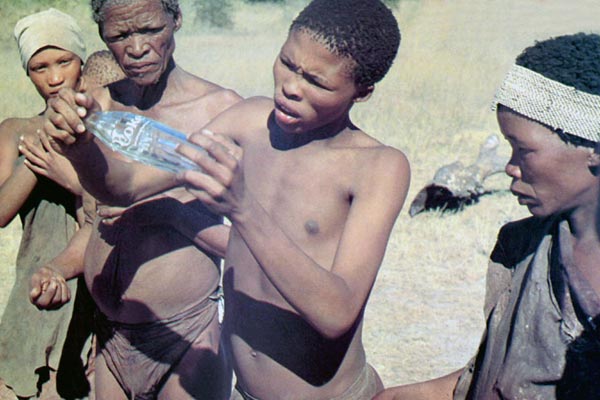

The West African country of Upper Volta, a former French colony with more than seven million inhabitants, was among the poorest countries in the world at the time of the popular uprising on 4 August 1983. At 280 deaths for every 1,000 births, it had the world’s highest infant mortality rate. School attendance hovered around 12 per cent and was even lower for girls. Thomas Sankara, a Burkinabé with military training, had witnessed the student and worker-led uprisings in Madagascar. He was influenced by what he witnessed there as a young man and returned to Upper Volta with an anti-imperialist worldview, founding in a strong notion and respect for the power of the grassroots. This put him at odds with the ruling party of Upper Volta and he was imprisoned in 1983. The people demonstrated in mass to protest his arrest and on 4 August 1983, Blaise Compaoré and some 250 soldiers freed Sankara. Sankara took over as president and formed the National Council of Revolution (NCR). He was 33 years old at the time. One year later the people of Upper Volta embraced a new national name, that of Burkina Faso - meaning the land of upright men.

During four years as the president, peasants, urban and rural workers, women, youth, the elderly and all ranks of Burkinabé society mobilised to create a more egalitarian and human-centred society. Sankara focused especially on the political education of the masses. A literacy campaign was organised and school attendance doubled in two years. He nationalised all land and oil wealth as a means of ending oppressive class relations based on landed property. An anti-corruption campaign was implemented. A massive reforestation project was undertaken as millions of tree saplings were planted to halt desertification. They sunk wells, built houses, and immunised 2.5 million children, including children from bordering countries.

Then on 15 October 1987, Captain Blaise Compaoré led a military coup against Sankara. It is widely accepted that the coup was in the interests of the landed and upper classes, whose domination was threatened by the revolution. Sankara and 12 of his aides were assassinated.

Blaise Compaoré remains the president of Burkina Faso today and has been implicated in conflicts in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Cote d’Ivoire, and in arms trafficking and the trafficking of diamonds. There has been no independent investigation into Thomas Sankara’s assassination, despite repeated requests by the judiciary committee of the International Campaign for Justice for Thomas Sankara, a legal group working in the name of the Sankara family. The UN Committee for Human Rights closed Sankara’s record in April of 2008, without conducting an investigation into the crimes.

SANKARA AND GENDER

To a rally of several thousand women in Ouagadougou commemorating International Women’s Day on 8 March 1987, Thomas Sankara took a distinctive position as a revolutionary leader and addressed in great detail women’s oppression. He outlined the historical origins of women’s oppression and the ways in which acts of oppression continued to be perpetuated during his lifetime.

He said:

‘Imbued with the invigorating sap of freedom, the men of Burkina, the humiliated and outlawed of yesterday, received the stamp of what is most precious in the world: honor and dignity. From this moment on, happiness became accessible. Every day we advance toward it, heady with the first fruits of our struggles, themselves proof of the great strides we have already taken. But the selfish happiness is an illusion. There is something crucial missing: women. They have been excluded from the joyful procession…The revolution’s promises are already a reality for men. But for women, they are still merely a rumor. And yet the authenticity and the future of our revolution depend on women. Nothing definitive or lasting can be accomplished in our country as long as a crucial part of ourselves is kept in this condition of subjugation - a condition imposed…by various systems of exploitation.

Posing the question of women in Burkinabe society today means posing the abolition of the system of slavery to which they have been subjected for millennia. The first step is to try to understand how this system functions, to grasp its real nature in all its subtlety, in order then to work out a line of action that can lead to women’s total emancipation.

We must understand how the struggle of Burkinabe women today is part of the worldwide struggle of all women and, beyond that, part of the struggle for the full rehabilitation of our continent. The condition of women is therefore at the heart of the question of humanity itself, here, there, and everywhere.’

His words display a profound understanding of, and active solidarity with, women’s struggles, of which he posits as a struggle belonging to all of humanity.

He locates the roots of African women’s oppression in the historical processes of European colonialism and the unequal social relations of capitalism and capital exploitation. Most importantly, he stressed the importance of women’s equal mobilisation. He urges Burkinabé women into revolutionary action, not as passive victims but as respected, equal partners in the revolution and wellbeing of the nation. He acknowledges the central space of African women in African society and demanded that other Burkinabé men do the same.

In an interview with the Cameroonian anticolonial historian Mongo Beti, he said, ‘We are fighting for the equality of men and women - not a mechanical, mathematical equality but making women the equal of men before the law and especially in relation to wage labor. The emancipation of women requires their education and their gaining economic power. In this way, labor on an equal footing with men on all levels, having the same responsibilities and the same rights and obligations…’.

This means that while the revolutionary government included a large number of women, Sankara did not believe that an increase in female representation was an automatic indicator of gender equality. He truly believed in grassroots organising and that change had to originate with the energy and actions of the people themselves.

He urged his sisters to be more compassionate with each other, less judging and more understanding. He questioned the need to pressure women into marriage, saying that there is nothing more natural about the married state than the single. He criticised the oppressive gendered nature of the capitalist system, where women (particularly women with children to support) make an ideal labour force because the need to support their families renders them malleable and controllable to exploitative labour practices. He characterised the system as a ‘cycle of violence’ and emphasised that ‘inequality can be done away with only by establishing a new society, where men and women enjoy equal rights’.

HIs focus on labour rights and the gendered means of production was symbolised through the day of solidarity that he established with Burkinabé housewives. On this day, men were to adopt the roles of their wives, going to the marketplace, working in the family agricultural plot and taking responsibility for the household work.

This speech provides a powerful heritage of political leadership and stands as a source of political ideas and inspiration for liberation movements on the continent. Sankara offers a possibility for continued male political engagement and solidarity with women’s oppression.

MILITARISM

Radical feminist theorists Barbara Sutton and Julie Novkov (2008) explain militarization as ‘how societies become dependent on and imbued by the logic of military institutions, in ways that permeate language, popular culture, economic priorities, educational systems, government policies, and national values and identities’. US-backed militarisation of Africa takes a couple of different forms. First, it means an increase in troops on the ground. US Special Ops and US military personnel have been deployed in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Mauritania, South Sudan, and (potentially) Nigeria.

Second, US military personnel conduct training sequences with African militaries. Training is underway in Algeria, Burundi, Djibouti, Chad, Namibia, Somalia, South Africa and many others. This is often presented as a ‘counterterrorism’ effort to stifle the spread of Al Qaeda across North Africa but it is a political tool. Bolstering local military capabilities in un-democratic nations is one means to ensure the control and suppression of local populations, who are often labeled as ‘terrorists’ to justify brutal crackdowns on social and political protests.

Third, the US military funds social science research into African society, culture and politics. This takes various forms, one of which is the use of SCRATs (or Sociocultural Advisory Teams) for the purposes of preparing US military personnel for deployment and missions. This can be understood through the same framework of contemporary counterinsurgency-style warfare in Afghanistan (and previously in Iraq), where winning the ‘hearts and minds’ requires in-depth knowledge of local peoples and cultures (what the military refers to as ‘human terrain’). British and French counterrevolutionary theorists during the anti-colonial period of the 1950s and 1960s also promoted the need for in-depth knowledge of local revolutionary culture and social organisation as a means of anticipating and controlling anti-colonial social unrest.

Although the US government claims that the US Africa Command is an extension of peacekeeping and humanitarian aid, an historical analysis of US intervention on the continent indicates otherwise. At every instance of African agency the US was willing and ready to intervene on the side of the colonisers.

In our contemporary moment, neoliberal promises and free-market policies have failed to return on their promises of increased wealth and progress. But more than this, they have caused increased social inequalities that is accompanied by a dangerous militarism. Scholars (see Sutton and Novkov 2008, for example) have explored the ways that increased poverty and the narrowing job markets caused by neoliberal policies pushes people into the military as a means of economic survival. This is true in the so-called Global North as it is in the so-called Global South.

The process of militarism is accompanied by gender-specific inequalities and disadvantages. Horace Campbell in his article, ‘Remilitarisation of African Societies: Analysis of the planning behind proposed US Africa Command’, (2008) explains, ‘Sexual terrorism…finds its echo in Africa where insecurities generated by warfare, ethnic hatred, rape, sexual terrorism and religious fundamentalism increase violence and lead to unnecessary military mobilization’.

The voices of African women activists and intellectuals are particularly necessary as the interconnections between militarism, masculinity and violence become clearer. Patricia McFadden writes, ‘By imbuing the notion of rampancy with political weight in terms of its use as a gendered and supremacist practice within militarism…[it] facilitates both class consolidation and accumulation, as well as gendered exclusion of women and working communities in Africa’. Women have been combating their exclusion through both organized and non-organized action.

A strong military structure paves the way for the resource plunder and large scale dispossessions that are seen in neoliberal states in the so-called Global South. In this system, the state ensures profit for class elites (both international and domestic) by guaranteeing the super-exploitation of labour and the dispossession of millions of people of their lands and livelihoods for resource extraction at serious costs to local ecology, health and wellbeing. This guarantee can only be made through an increased militarism that stifles political mobilisation.

But Thomas Sankara and the August Revolution of 1983 tells us another story. They provide a different way of thinking about social organisation. Sankara understood that capitalism is dependent upon the unequal deployment of and distribution of power, particularly state power. But, as he showed us, the state is not unalterable. The state is a complex system of human relationships that are maintained through violent power/coercion and persuasion. And what Sankara did was work to bring the state apparatus down to the level of the people, so to speak. He encouraged people to engage with the state and to change the unequal power relations embedded in the state structure. He did this - as demonstrated earlier through the example of gender empowerment - by exposing the ways that power is generated, controlled and dispensed and then identifying alternative forms of social relations. This is what the August Revolution of 1983 sought to perform in Burkina Faso.

The life and work of Thomas Sankara can be taken as a reminder of both the power and potential for human agency to enact transformation and as a reminder of our obligation to engagement of and for human wellbeing. As the social mobilisations taking place across the world are demonstrating right now, this engagement for human wellbeing means refusing to submit to neoliberal policies that see humans in terms of labour and profit.

CONCLUSION

I’ve been told that the first time that my daughter’s paternal grandfather cried was at the news of Thomas Sankara’s assassination. It was certainly the first time that my daughter’s father saw his father cry. He recalls, even at the age of seven, his sense of confusion and sadness over Sankara’s death.

The image of my daughter’s grandfather entering his home and collapsing onto the sofa, holding his face in his hands and crying emerges in my head each time I think of Sankara. This image of a middle aged Cameroonian man, Jacque Ndewa, thousands of miles away, who had never travelled to Burkina Faso, crying quietly on his sofa. This is the resonance that Sankara had, across the African continent and among disenfranchised and dispossessed people everywhere.

In honour of his memory, I praise and celebrate his fearlessness, his resilience and his political leadership for human emancipation.

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* This text is from a presentation by the author at a Revival of Pan-Africanism Forum event entitled 'Celebrating the Life of Thomas Sankara' and held at Jesus College, University of Oxford on 8 June.

* Please send comments to editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org or comment online at Pambazuka News