An interview with

Viva Riva! director

Djo Munga

Everyone who’s seen Viva Riva! raves about it. A Congolese film noir written and directed by Djo Munga, the film has been racking up awards at international film festivals (the latest, just a few days ago, for "Best Feature" at the AITP Film Festival) and earning praise from even the most exacting film critics and publications — Time Out New York called it "One of the best neo-noirs from anywhere in recent memory"; Sight & Sound, after describing the film’s premise writes "But if that outline suggests a standard genre piece with a novel setting, Viva Riva! is much more than that," and goes on to praise its energy, ideas, candid performances by the cast of non-professionals and unprecedentedly frank sexuality, and concludes: "…with its quickfire shifts from sex to violence to betrayal and back again, that exclamation point in Munga’s title is fully earned." Such accolades are no small feat for a first-feature director.

So a short while ago we sat down with Djo Munga to find out just how he did it — his inspiration for the film, the casting and rehearsal process, shooting in Kinshasa. He talked about about the film’s reception in different parts of the world, the Congolese film industry, his dream collaboration, and much more.

Director Djo Munga

TIA: What inspired you to make Viva Riva?

DM: I wanted to make a film that would allow me to talk about the reality of Kinshasa, and at the same time be entertaining, but I didn’t want to do it through social-realism, the typical documentary-like style of filming when trying to “capture” Africa, because that can be boring. I wanted to communicate to the masses. Culturally speaking, the Congolese — and black people in general — we have a need for cultural products that represent us in ways we can be proud of while remaining entertaining. This doesn’t mean I want to make films that ignore the problems; that’s not the case. I just wanted to experiment; I wanted to make a hugely entertaining film that could also reflect the last 20 years of Kinshasa’s history.

TIA: I notice that African filmmakers can feel pressured to make films that are politically charged or socially engaged. Did you feel that pressure?DM: Well, I don’t see it as a pressure. I think it’s necessary at this stage in our history, as Congolese and Africans, to have a political point of view. There are some important issues that we should talk about, and it’s perfectly normal to talk about them, but I think the way we talk about these issues is also very important. In other words, the form the message takes to reach the audience is important. The way I see it, knowing the level of literacy in the Congo, you can’t as a filmmaker go, “I’m going to make a film about this complex situation and if people don’t get it that’s their problem.”

I was inspired by what Latin American writers did many years ago. I remember a guy by the name of Eduardo Galeano; he wrote the book… I forgot the title in English but you can check it, Les Veines Ouvertes de l’Amerique Latine (Open Veins of Latin America) and actually he was explaining the history of Latin America, but he did it as a soap opera to make it easy for people to understand and to be entertained. When I read that book as a student, I was like wow!, maybe this is the way we should do it. We need to find ways to reach the masses when talking about important issues, and you can do this while being entertaining.

TIA: I hear that most of the actors in Viva Riva! weren’t professionally trained. What was the rehearsal and casting process like?DM: In Kinshasa, like in many poor countries, you have a lot of artists – I mean people who are doing what they do for the love of it; it’s the meaning of their lives, and they don’t do it for the money or for whatever reason. So in the misery of Congo we have a kind of luxury to have all these artists available and ready to work. So I said to these guys, “You have a lot of talent and you are good at what you do, but let’s go into a workshop where you will learn the techniques of working with the camera, and of working in film. And they came and worked for two months, you know, just discovering their bodies and how to work with the camera, etc. And after that, we stopped for a year — I mean I sent them back to their daily lives and they came back the next year for production. Then they started to work with an acting coach in terms of developing their characters and [learning] how to get deep into a script. After two months of this, we started rehearsing. I gave them the script, and they rehearsed every day, maybe like three hours every morning. So yeah, it was a real pleasure. It didn’t feel like work, to tell you the truth. We had a lot of fun…I think (laughs).

TIA: I think most creative works reflect the artist in some way. If I am right, how do you personally relate to the characters of the film?

DM: (Laughs). That’s a tricky question. Well, I relate to many of them, so it’s difficult to say which one is closest to me because all of them are a part of me in a way. So I can see how “the commander” was more or less like a tyrant, but suddenly she was stuck in a situation and she started to change and then she becomes someone else — that happens to all of us.

And with Riva, I can see also the way he avoids facing problems, and how his family’s problems are like mine. So all of them are like me in some ways. I think the way I write stories, I mean because I have many characters, is a way of putting yourself in various situations and trying to be as true as possible to the character and different situations.

TIA: The film has been traveling the festival circuit for a while now. Where are some of the places it’s screened?DM: All over the world, more or less. We showed it in Kinshasa first as a test, then we screened it at the Toronto Film Festival, Berlin Film Festival, at festivals in Austin, Texas, France, England, Ireland and Hong Kong. It was very surprising that the film sold out in Hong Kong. This says something, actually, because we often think that China’s too far from us, and I thought they might say this is not for us. But why should they say that? People are interested in stories, no matter where they're from. So for me, it was very good screening in Hong Kong. I was really amazed by the audience – they were really warm, they liked the film, and I had a really exciting interaction with them afterwards, so I was really happy; I was really pleased with the audience.

TIA: So are you surprised with all the positive reviews that your film has earned?DM: Totally, totally surprised. Look at it from this point of view: I studied in Europe, in film school, so from the European point of view, you have this sense that, well, America is only interested in American films which is basically Hollywood and maybe some independent films, and that the rest of the world really doesn’t exist and Africa exists even less. That’s the point of view we had. But then the film was shown at the Toronto Film Festival and an American distributor was the first to buy the film and actually, the film’s first theatrical release [in the States] will be in New York, which is a sign really, a really big sign that maybe I was wrong to think the way I did. I mean since September, when the film opened in Toronto, it went really deep into my mind – I was thinking what does that mean to me now? It also broadened my vision of America: So “Okay, we like your film,” so I’m welcome.

They took this film as they would a French film with Catherine Deneuve; I mean, she’s a bigger actress but still, it says something. Also, as a black person, it says something that I don’t have the feeling of [being] a sellout or someone who made a film just for Westerners. I feel like I’m just a filmmaker who made a film that people enjoyed. So it was definitely a big surprise, and that surprise was confirmed at the SXSW Film Festival and also yesterday, when I came to Baltimore, by the reception I got. So yeah, all the positive reviews have been a big surprise, a really big surprise.

TIA: It seems like our cultural backgrounds often influence the ways in which we interact with films. How has the reception been different in different parts of the world?

DM: African audiences loved it, at least in Congo; it was a big thing. But I was surprised that people [at film festivals] in America found the film violent. There were a lot of comments about that. I was surprised because they have all these action movies and TV shows on American TV. So there must be a reason why they find the film violent. I think maybe it’s because of the way the film is shot – it’s a bit different from the films they’re used to seeing. It’s not shot like a documentary but I think it takes you close to the characters the way a documentary takes you close to real people, so they get into the story more and feel the violence a bit more.

In Hong Kong, they said the same thing. They said we are used to Chinese action movies, but we know they’re not real. But in Europe they didn’t say that. They felt it was different, so those are the type of reactions I received.

Africans didn’t comment on the violence at all. Maybe because part of it was reality, I don’t know, but the African critics and journalists have been very, very supportive of the film – especially Nigerians. They feel that maybe this film is a change or offers a possibility for change for the industry in the future. I hope it will. And I’m really happy about it.

TIA: One of the recurrent criticisms of the film is that it portrays African women in negative, stereotypical ways. How do you respond to that?DM: Well, some have said “he portrays women in a negative perspective,” but others have said I’m a feminist. Of course, I prefer to think of myself as a feminist.

Women face big problems in our society, especially in Congo, and I think I’ve tried to address these problems through the film’s female characters. Nora, for instance, is a beautiful woman trapped in her world and in a particular life, but with Riva, maybe she has the possibility to escape. Then there’s the commander who is maneuvering in society and tries to be free, but she can’t really, and her friend, Malou, and also the women of GM. It’s like different perspectives on Congolese women I tried to put. I don’t think I was negative in that sense. I tried to look at reality and of course, I could talk about the happy women who just got married and life is fantastic and all that, but in a country that is 167th poorest in the world, life is not easy and especially not for women, so that’s what I tried to show.

TIA: Since this is your first feature film, perhaps it’s too early to talk about legacy. Nonetheless, how would you like to be remembered as a filmmaker? And will all your subsequent films take place in African settings?DM: Well, if people remember the films I made and the stories I told and enjoyed them, I would be happy. When I think about Sergio Leone, I don’t think about him being Italian – I just think about the great movies he made. Or if I think about Fritz Lang, I don’t think of him as being German or going to the West and then coming back – I just think how great of an artist he was. So I think of myself as an artist, and as an artist I try to do films in different places - which I have done. I shot a documentary in Ireland a long time ago, I’ve had projects in various parts of the world, and it’s important to me that I stick to that.

TIA: So what’s the film industry like in DR Congo?

DM: Nothing. There's no industry in the classical sense, because when you talk about an industry, it means that there's a structure, it means there are schools, there are systems in place for raising funds, hiring people, making films, and also finishing the films as in doing post-production work with all these labs and infrastructure to release the films once they’re made in order to recoup your costs. That does not exist; we only have what I call “gunmen”, like me, and various directors. We try to find opportunities to make films, which is basically as tough as robbing a bank, but that’s what we do. But I hope there will be an industry 20 years from now. One part of my work is that I do training programs. I try to help young filmmakers learn their craft, so that one day they can make films themselves.

TIA: What is your advice to aspiring young African filmmakers?DM: Study. It’s very, very important. I hope I don’t sound too conservative, but still it’s important to be able to read great writers – like James Baldwin, a fantastic writer, Chester Himes, a fantastic writer – they are all very big writers, including African writers like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. Those are some of the more famous ones. And also to watch a lot of movies, classical movies. I mean I strongly believe education is the key to development. It’s almost impossible to develop without an education, except for a few people.

TIA: What are some of your future plans?DM: First I’ll try to survive, which means I’ll try to find a way to make the next film. And making a film is also interacting with the industry. It means having a story and finding partners to invest. You know, I’m just in the business like everybody else, and I’m a small fish. So I’ll see where there’s a possibility for the next film, and I’ll try to do something.

TIA: Who are some actors and directors that you would love to collaborate with?

DM: I think Number One on that list would be Forest Whitaker. If I have the opportunity to work with him, I definitely will. I would also love to maybe adapt a book by someone like Chinua Achebe, or Alain Mabanckou, who is a Congolese writer. I think it would be challenging, and it would be something very interesting to do. I mean if I had the money, I would definitely do it, because I would love to bring his (Mabanckou’s) work to a bigger audience.

TIA: Lastly, what is a common misconception about living in Kinshasa that you would like to dispel?DM: Misconceptions… I think the biggest one is… I want people to know that Kinshasa is actually a safe place, that most of the Congo is very safe. People refer to the Congo as this heart of darkness and this place where you can’t really live properly, which is not true – not at all true. I think this is the biggest misconception about the Congo.

Interview by Yves-Alec Tambashe

Djo Munga photos by Shako Otekavia thisisafrica.me

__________________________

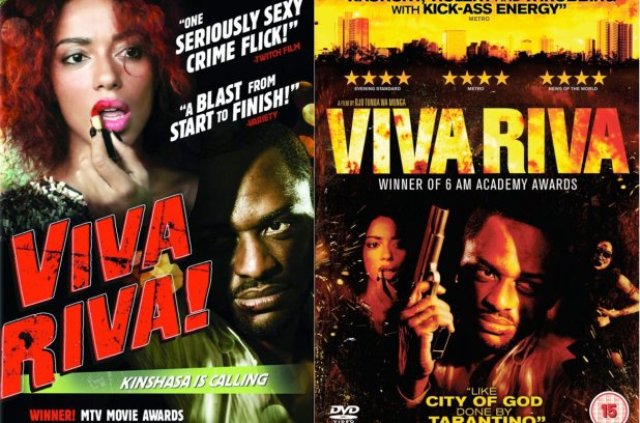

INTERVIEW:

TWITCH TALKS EXCLUSIVELY

TO VIVA RIVA! DIRECTOR

DJO MUNGA

by James Marsh, May 23, 2011

One of the most exciting discoveries of the year, the slick, violent and seriously sexy crime flick from Congo, VIVA RIVA! is coming to the US. The film scooped six prizes at the 2010 African Academy Awards, including Best Film and Best Director and opens in New York and Los Angeles on June 10, before spreading out to selected cities across the country in the following weeks. I guarantee it will blow apart any preconceptions you may have of African fimmaking. Through the powers of the interwebs, last week I was able to chat with writer-director Djo Tunda Wa Munga about being an adolescent film fan in war-torn Zaire, how he was able to produce Congo's first feature film in 20 years, and his future plans to make the ultimate Africa/Asia gangster epic!

JM - VIVA RIVA! blew me away. It's exciting, sexy and stylish in a way I didn't expect from a film from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It's clearly made by someone who knows & loves movies. As someone born and raised in Kinshasa, tell me about the films that you saw growing up.

DM - It's probably difficult for people to imagine, Kinshasa in the 70s was very different. There were two theatres in my neighbourhood, so I used to watch a lot of films. These were mainly Westerns - Sergio Leone's movies, Django and all these guys. Also we had kung-fu films, a lot of Bruce Lee and all that genre. And of course we had a few French movies, but I don't really remember them. Also King Kong and these Japanese things like Godzilla, they were really important.

JM - So there was no chance of you ever making romantic comedies then?

DM - [Laughs] I didn't think about it at the time, but you know, in a dictatorship like Zaire (as the DRC was known between 1971-1997) you basically had gangsters running the country, so there's probably a certain mindset that identifies with gangsters and violence rather than with romance or comedy. That's probably why SCARFACE is one of the most popular films in Africa, even 30 years after its release, because people relate to that world.

JM - How old were you when you decided that this was something you wanted to do, or realized it was something somebody could do professionally?

DM - Oh it was not that easy. When I moved to Europe I studied at Art School and my aim was to become an oil painter or get into advertising or become a cartoonist. But one day I wandered into a filmmaking workshop, and I wouldn't say that I enjoyed it at that moment, but something happened. It was very difficult, as an African, to say to myself I'm going to make films for a living, and it really was at the last minute that I realized there was something important there. So then I applied to a film school in Brussels.

JM - When you left Kinshasa for Belgium, did you go alone or with your family?

DM - At the time people were aware that Mobutu (Zaire's dictator) wasn't putting any more money into education, and eventually the system collapsed. So, people who were Middle Class or Upper Class, like my parents, sent their children abroad to boarding school. So I went away for five years and my parents would visit from time to time. I arrived in Brussels in 1981, was at boarding school until 1986, started art school in 1988 and entered film school in 1993.

JM - Were you influenced in any way by the European style of filmmaking?

DM - [Laughs] No, not at all. Twenty years ago things were quite different. I'm not saying there were racial issues, but you would stick within your own community. You go to school, you have friends, but apart from that their wasn't really any connection to the French or European communities.

JM - So you found yourself living mostly with other African expatriates...

DM - Yes, exactly. But instead what I did was, do you remember the old videotapes, VHS? Back in the early 80s we had the first video club, at least in Europe, which was a little thing for specialists. We had all the horror movies, not so much the action, but the classic movies, which were available. So every weekend I'd go down there and chat with the guy and that's how I discovered Cronenberg and all the horror greats of the time, as well as interesting directors like Coppola, Scorsese and all these guys. So in terms of film and culture, my education was more through the cine club, and VHS was really important.

JM - So after you acquired your filmmaking education...

DM - Well I'm still not sure I feel qualified! I still have the same questions as I did 18 years ago when I started film school. I always hope that the next film will give me the answers but it never does really. But let's see.

JM - Weren't you tempted to head west to ply your trade as a filmmaker? What prompted you to return to the Congo, where there is no industry?

DM - I think it was the Toronto Film Festival, 10 years ago they had a section called Planet Africa and I had a short film playing there. When I came to Toronto and showed my film, which was a modest story about a little Congolese boy living with his sister in Belgium, I was really surprised how much the audience liked and understood the film. For me it was like that moment when you see the light, I realized that I could go back to Congo and make films there and enrich the international audience. Also, 2001 was a very difficult time in Congo because of the war, but there was this question of responsibility, in terms of at least trying to do something in Congo. We were supposed to leave, study, and then come back. That was the debate, and I decided to go back.

JM - When you returned and tried to get your project off the ground, what was the local reaction? Were people supportive or did they think you were crazy?

DM - People didn't really believe that it was possible, and I'm not the type of person to convince someone to do something if they don't want to. So I embraced it as a personal journey, but at the beginning it was not very successful. It was really tough, really difficult.

JM - Did you have any connections or people that you could go to for help and support?

DM - No, not really. I started work as a line producer in documentaries, so I did little jobs for Belgian television first, then I got a big job with the BBC. I made a film for them in 2003 about King Leopold (WHITE KING, RED RUBBER, BLACK DEATH about the Belgian monarch's acquisition and exploitation of Congo). After that, a Danish production asked me to work on something else and I entered into this world of making these historical movies, which were very interesting and I met great people. After that I kept working, I wasn't making a lot of money but that wasn't too important.

JM - Your background in documentaries is hugely evident when watching VIVA RIVA! and your ability to capture the local environment authentically. What was the response from the locals while you were filming on location?

DM - People were really easy, and sometimes I was even embarrassed because we were shooting in these very poor areas and people were inviting us into their homes to film. And I wanted it to be real, but you hit that point when you ask yourself do we really have to do this? Is this fiction or is it documentary? But they really made it very easy for us on all levels. Whether we needed a house or a car or when we were shooting the nude scenes - the women were asking me why I wanted to do it and I told them that the idea was to be as real as possible, to accurately portray our society today. Once they got that, it was easy.

JM - I imagine you used a lot of non-professional actors, real people playing characters similar to themselves.

DM - I tried to tell them to invent a character who looks like you and talks like you but is a bit different. There is also a culture of improvising, so we rehearsed a lot and they were changing dialogue so I used these changes and incorporated them into the script. So it's that combination - part of them, part of the script - and finding a chemistry that works.

JM - Some of your lead actors, like Patsha Bay (who plays Riva) and Manie Malone are already professionals. How did you find and recruit them for the project?

DM - I had many levels of casting. I hired a French casting director, who saw about 350 or 400 people maybe, and she selected 20 people. And that included most of the main cast of the film, except Manie, Patsha and the Commander was not there either. I bumped into Marlene (Longange), who plays the Commander, whom I knew from her theatre work, but she told me she had stopped acting because it was too hard. I invited her to the casting anyway, just to see if she was interested and of course she was great!

For Manie (who plays the film's femme fatale, Nora) it was more complicated. I was aware there might be a problem finding an actress in Kinshasa willing to do the things Nora does - or anywhere in Africa. I mean, the nude scenes and the violence, it's not usual. So I wrote the character as someone who could be foreign. Also, I couldn't find anyone in Kinshasa who had that magical spark needed for a woman in a gangster movie. These femmes fatales must be special, right? Then at the last minute, by accident Manie came to a casting in France. She had this glow, she was both wild and elegant. But I didn't give her the part right away, I invited her to come to Kinshasa for two months' training, to learn Lingala and to explore the environment and then if she got through that I'd give her the part. And that's exactly what happened, she came, she's a hard-working person, very motivated and she got the part.

JM - So what's next for you and next for Congolese Cinema?

DM - Well what I have in mind next is to set up a Congo-China story, which is why I was in Hong Kong for the festival, because I wanted to meet people. In the last 20 years we've seen a huge migration of Chinese into Africa and China has changed Congo, but also the Chinese change when they move to Congo. This is an interesting dynamic. It'll be a feature film, a gangster film - another film noir, because I feel comfortable in that genre.

JM - So there is some tension with Chinese gangs setting up in Congo?

DM - Yes but I want to describe both worlds, you know, the Chinese gangs, but also the Congolese gangs, but they're more like bankers and people in the government - these are all the gangsters in Congo! So the good guys - a Chinese cop and a Congolese cop - will be teaming up, trying to do something.

>via: http://twitchfilm.com/interviews/2011/05/interview-twitch-talks-exclusively-t...

__________________________

Djo Munga:

The Art of Pushing Boundaries

in African Cinema (Part 1)

posted by Belinda Otas

“In Kinshasa, every day is a struggle and every night is a party. In a city where everything is for sale, Riva has something everyone wants.” – Djo Tunda wa

Munga’s debut feature film,Viva Riva! had cinema buffs the world over in awe. Set in Kinshasa, DRC, the film depicts the country’s tumultuous existence as it chronicles the life of Riva, an ambitious mobster in the making, who returns home after spending a decade in Angola, only to find the country in dire straits as a result of fuel shortages. What unravels is an enthralling story of frank realism that includes crime, violence, disorder, corruption and sexuality, revealing the myriad complexities of Kinshasa and its citizens. In his own words, Djo Munga and the art of pushing boundaries in African cinema.

Belinda: Why was it important to tell the story of Viva Riva the way you did?

Djo: This was the first film in 26 years in Congo. When you realise there is no film industry in your country and you are producing the first film in 26 years, you really want to do something different and make a great film. At the same time, you want what you have to say to be personal and important and for people to understand it. In that sense I wanted to talk about the city of Kinshasa because that’s my hometown and many people can relate to it. In the global sense, it was really important to try and describe the city in a way it has never been described. You talk about night life, the problems that we have and it is important to address certain issues and I also wanted to explore the last 13 years of the city, the war, violence and the change, you know, the new Congo, the crisis and shortage of (fuel) petrol/gas because the shortage did happen in 2001, among the other important elements that was vital to this story.

Belinda: What significant impact has it had in terms of shaping different narratives about the DRC since it was released?

Djo: We had a couple of screenings in Congo, and had close to 300/400 people and of course, we were nervous and not sure. But the response was like wow, this is us and it was like have something where you can recognise yourself. The film opened at the Durban film festival (2011) which was the official African premiere and it was the same. It was a really, really big success and people took ownership of that and the young people were saying how proud they were to have a film about themselves. Also, I think this is the first time, they may see a film where the people look like them and at the same time, it is like an art house movie – it has entertainment and is directed by an African director, with the same level/standard of an international film. The reception has been great.

Belinda: Why the name Viva Riva!?

Djo: (Laughs) the salsa bit is very important in Congo and the term Viva, Viva La Monica, which is a popular band in theCongo and it’s a reference to Salsa. So I picked the name Viva because it is a way of praising the sense of freedom

Belinda: I understand you come from a documentary background. I think it is fair to ask how you were able to marry a documentary background, art house and entertainment. Was it very challenging to approach the issues you bring to the fore in the film?

Djo: It was a challenge because for me, when we look at the Congo, we don’t have a cinema, we have a high level of illiteracy in the country and making a film, you want to focus on the issues and elements for the art house and at the same time, you want it to be accessible. That was the reason why I chose the genre of the film. To achieve the art house vision, it was important for it to be close to a documentary. So, it is like a thriller but in a documentary context. So we shot in Kinshasa in the mode of a documentary/style. We went on location and shot the city based on how it was. It was really delicate to balance. It was kind of a film noir vision and at the same time, an approach/take on reality.

Belinda: Viva Riva! has been described as “a tough, sturdy thriller, centred around a small-time hustler called Riva (Patsha Bay), who shows up in the fuel-starved big city with a truck of petrol he’s liberated from his Angolan gangster employers” why did you want to use the metaphor of fuel/petroleum, the lack of it and huge hunger that people have for it as the basis of your film?

Djo: Wow! That’s a question no one has ever asked me. (Laughter) I mean, there was a shortage of gas in Kinshasa in 2001, and there was also one in Zimbabwe. When there is a shortage of gas, everybody is affected because they feel trapped and when you have fuel, you can go anywhere. So, you are kind of like in a prison in your own country. And certainly, Gas is so important that I would compare it to drug addicts. If they don’t have it, suddenly, that hunger you are talking about becomes some sort of a crisis. This is also the way to link all the stories together because everybody is kind of in the same problem. When you talk about a city and when a city is functional…not having gas can show how dysfunctional the city can be and on a bigger scale, it will show you how people can get greedy and fight for the same thing. (Hunger in society for gas could also be a hunger for change)

Belinda: It has also been described as a “gory, fast-paced gangster movie that gives a unique insight into Kinshasa’s ruthless criminal underworld.” We know about war and the reign of terror dished out by rebels on innocent civilians but we often don’t hear the narrative of violence within the scope of ongoing day-to-day life in Kinshasa. What was it about the violence and pain that we as human beings inflict on each other that you wanted to examine?

Djo: In addition to the gas story, I wanted to explore the effects of capitalism and the violence that happens in Kinshasa and in the Congo. It is a violence which is directly driven by a greed for minerals. In the civil war, for example, like the uprising that you have seen in the Arab world, it is about internal and external forces fighting against the west. In that sense, what I wanted to say about Kinshasa in the story – my tone and intention was ultimately to say Congo has a negative image. It is time to make something different and tell a different story. I want to talk about reality. So what I did was to go to the people’s level and talk about them. People have a life in Congo, every aspect of life and the life goes on and they manage to survive. But also, the violence is a way to depict… I mean…if people think capitalism is good, go to Congo, go and see the effect.

Belinda: What authenticity were you aiming to bring to the screen about ordinary life on the streets of Kinshasa?

Djo: I wanted to emphasise how people manage top cope with everything. The film also has humour and you can see that people have desires and go about on a day to day basis and deal with all of that.

Belinda: Now you also have one scene where an Angolan is looking down on a Congolese. Now this is one topic we as Africans are uncomfortable talking about. We will gladly talk about western colonisers but we don’t talk about the fact that we also look down on each other. Why did you want to address that issue?

Djo: Well, because we don’t talk about it and we don’t talk about ourselves and to be honest, it is very important to raise these issues. In my country where I see the UN mission, which also has many Africans, the attitude there and hierarchy is also questioning what it means to be a Pan-Africanist and be African. There is a racist attitude that we see elsewhere with white people and it is worse because they are Africans and I think all that is part of underdevelopment. The racism that we have among ourselves, the lack of empathy that we have among ourselves and the lack of everything. It is also a question of society. The film is not just about entertainment. It is also a mirror on what the society is.

Belinda: Is it too early to say that with the work you are now doing on the ground that a cultural renaissance is on the horizon?

Djo: Oh that’s too early because it is currently on the individual level and to talk about a renaissance you need to have different elements that are coming together and people coming together and pushing it…but I would love to have a renaissance but let’s see realistically if that will happen.

(PART 2)

Belinda: When it comes to breaking barriers, especially on the issue of filming sex and sexuality in African cinema, how far did you want to push that boundary and why did you want to go there with one or two of the sex films in Viva Riva!?

Djo: I wanted to push as far as possible and what you see in the film, we are not making a porn film. Look at most African films, there is a night life and sex is part of the life of people…we have doctored ourselves for so long, it was important to me that we push and see…for example, we know that in Kinshasa, the problem of prostitution is quite huge and we have a city that is sexy in the sense that all the relationships between men and women and their sexuality is kind of rich. So, it was okay to say we must have this in the film but the point is not around that. It was not a point about being naïve but about looking at Africa and saying this is now and today. And it is also a genre film and together, it worked well.

Belinda: I understand you trained everyone involved in the film. Was this because there were no trained actors and crew members and what does this say about the current state of the Congolese film industry? Or was it a case whereby you wanted an organic end product?

Djo: We have no film school or institutions, nothing. We have people who have talent but that talent is not enough. We needed to teach people how to use that talent for the camera and then it became an organic work. We had to train the actors, the technicians and that’s the way things were across the film, Viva Riva!

Belinda: You show us a busy and bustling night life despite the fact that the news media would have us believe, people are locked away in their homes as a result of fear, the raping and looting we hear so much about in the news. What do you hope your film adds to the narratives of DRC and Africa as it is today?

Djo: Well, when people ask and many people write to me and say we are really proud that you have made that film. It is also the fact that people question Nollywood and you have a lot of journalists saying this is what Nollywood should do. I think it is a sign that I brought something new. Maybe like a new direction and the fact that the film is a success and has opened in these different and many countries, US, UK, Australia and South Africa. It is also a sign that first, as an African director, we have something to say to the world and the world is ready to listen to it and Africans are also ready to listen to it. And people enjoy the film. And in terms of identity, we are building our confidence.

Belinda: Let’s talk about Africa’s famous film industry, Nollywood, why do you think it has been so successful and what do you think, it will take to show African cinema beyond Nollywood because there are other film industries taking shape, from Ghana to Liberia?

Belinda: Let’s talk about Africa’s famous film industry, Nollywood, why do you think it has been so successful and what do you think, it will take to show African cinema beyond Nollywood because there are other film industries taking shape, from Ghana to Liberia?

Djo: Nollywood has been successful in terms of its ability to respond to the need of African audiences to have their own imagery on screen. That was I believe, the moment when people dreamt of Africans in the scripts even if the stories were not good, at least it was some kind of their imagery, which if you compare to certain cinema, certain art house cinema for example, they are well directed but people just don’t follow. African cinema just didn’t have that then, it was like they failed to represent the people and so Nollywood was an answer, in order fill a void. At the same time, Nollywood is a reduced form of quality and in that sense that didn’t work and that’s why I think Viva Riva! did so well and to so many people, it was an answer in terms of telling an African story. It is telling a story with modern entertainment, quality and imagery. I think the film was answering to that.

Belinda: The film has created a new narrative about Kinshasa. are you now under pressure for your next film to deliver?

Djo: (Laughs) no, I feel more confident in terms of wanting to push further and I am more eager to do better and put more elements. But first I feel more pressure to raise the money and to be able to make the film. It is not because there is an interest that you do it. All the elements have to come together. I feel pressured to have all the elements together.

Belinda: Will the lack of funding will be an issue for your filmmakers who will see what you have done and want to emulate you?

Djo: Of course, it is terrible that African filmmakers have to go to western countries to find money. And that is a problem and a really big problem. And I hope that at some appoint, the government of the different African countries will be able to change the attitude to funding?

Belinda: Are you working on anything at present and when should we expect another film from you?

Djo: I am working on a Chinese/Congolese story, a gangster movie also set in Kinshasa and. It also a look at what is Africa today?

>via: http://belindaotas.com/?p=10659