When Gil Scott-Heron passed away last May, the flurry of obits, essays, and think pieces that followed principally presented him in two specific lights-- as the man behind the much-quoted (and misquoted) catchphrase "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" and a presage of hip-hop. He was 62 years old when he died and had recorded 15 studio albums and written two novels; his postumous memoir, The Last Holiday, was released this week. Gil was a poet, a novelist, a singer, a songwriter, a pianist, a satirist, a father of four. In revisiting his catalog and talking to the people closest to him, it doesn't take long to see past the catchphrase and recognize him as a much more complex artist and human.

Well before his journey as an entertainer began, Gil's biography was a fascinating one. He was born in Chicago; his mother, Bobbie Scott-Heron, sung with the New York Oratorio Society and his father was a Jamaica-born professional soccer player. His parents separated when Gil was two and moved him to Tenneesse, where he was raised by his grandmother. There, he was one of the first black children to be integrated into the state's school system.

By 12 he moved north to live with his mother in New York, where he would befriend classmate and budding hoop legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as a teen. (They remained friends for the decades that followed, with Kareem serving as best man in Gil's wedding to actress Brenda Sykes. When Gil passed, Kareem penned a brief but heartfelt eulogy on his blog entitled "Goodbye Gil Scott-Heron".) After graduating high school, Gil attended the HBCU Lincoln-- alma mater to luminaries such as Langston Hughes-- but dropped out to finish his first novel, The Vulture, which established him as a talent with both politically charged impulses and a knack for writing in the then-hip voice of the streets.

Larry McDonald, percussionist: There are two Americans I could listen to talk forever: Gil and Richard Pryor. The way they used "black English"-- they could curse and swear and say the most outrageous things, and it didn't seem obscene because it was totally in context.

Larry McDonald, percussionist: There are two Americans I could listen to talk forever: Gil and Richard Pryor. The way they used "black English"-- they could curse and swear and say the most outrageous things, and it didn't seem obscene because it was totally in context.

Lurma Rackley, girlfriend and mother of Gil's son Rumel: Coming on the heels of the civil rights movement, everybody was open to the realities that each person had to do something and be involved. All across the country and the world people were paying attention to the huge shifts that were going on-- the end of segregation, the efforts to end Apartheid, the focus on nuclear energy, the whole Nixon debacle. There were powerful political happenings and he was so brilliant about tapping into them in a way that people could understand. He was tapped into the energy of the time and he made extraordinary commentary on the major issues of his time. The commentary is still valid today.

For all the power in his message, Gil frequently struggled with the reductionist assumption that he was just a political firebrand.

"I don't know if I was as angry as much as I was misunderstood.

A lot of the things we did contained a lot of humor that went over people's heads."

McDonald: One day he said to me, "Man, I don't like how they have me as this black spokesman. When they do that, they're setting you up so they can shoot you down. I've got too many skeletons in my closet. I don't even want to be bothered by that." So I said, "Why do you go down this road?" He said, "I saw some shit that needed to be spoken on and nobody was speaking on it. So I just said it."

Gary Price, housemate: Everybody talks about "The Bottle" and "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" and "Angel Dust", but some of the more emotional pieces like "Song for Bobby Smith" were my favorites. That song has no social or political things going on at all-- it's just a beautiful song.

Rackley: He had a soft side, too, and a lot of people were attracted to him. He talked about his grandmother a lot and her connection to the earth and to doing what's right. I think that infected his approach to the world in a positive way. He also had a pretty deep belief in the spirit world, he even named one of his albums Spirits. He felt that his ancestors who had gone on before him were still available emotionally and spiritually.

Gil, BBC's "Hard Talk", 2000: I don't know if I was as angry as I was misunderstood. I think that a lot of the things we did contained a lot of humor that went over people's heads. We were clearly coming from a small southern town in Tennessee and we didn't estimate what effect we'd have on national and international governments. We were trying to represent our community and speak about the things there. If people don't understand the humor then it's angry, but if people see the juxtaposition of the ideas then they understand where we're coming from. Langston Hughes and Paul Lawrence Dunbar and people of that nature always felt that humor was the best way to see a point of view.

Much of Gil's catalog is dripping with sarcasm and subtly deadpanned double speak, even in his most harrowing moments. He also had an obvious love for slapstick verbal puns and could bend language in all different directions almost as a natural tic. (This sort of wordplay might be one of his more blatant predictions of hip-hop.)

Rackley: People who saw his shows would get a taste of that because he would start off with a monologue and it was always so funny. Like when he goes into the "H20gate Blues" and he talks about the different shades of the blues-- the "I ain't go no money blues," the "I ain't got me no money blues," and the "I ain't go no woman and I ain't got me no money blues, which is the double blues." He was able to find humor in almost everything.

Gil, Mediawave Festival, 2010: I think everybody has six senses, and the sixth one is your sense of humor. And that's my most valuable one. I can imagine myself without the other five, but I can't imagine myself without my sense of humor.

These popular misconceptions might have to do with his biggest hit. For all of its impact, "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" had the side effect of narrowing the memory of Gil's work. That tiny string of words wasn't a mission statement, just one small fragment of his message. And a tongue-in-cheek one, as well. The poem was heavy with bluster but weighted with wordplay. In it, Gil critiqued crass sloganeering, mocking everything from Agnew to Ajax campaigns. The bitter irony, of course, is that it became a slogan itself. "He was commercialized by the [current] generation," says Leon Collins, who lived with Gil in D.C. throughout the 60s and 70s. "That's been co-opted and exploited a billion different ways." As time passed Gil himself seemed mostly indifferent to these developments, though quick to clarify his original intent.

"[The revolution] is not all about fighting and going to war-- it's about going to war with a problem and deciding how you can affect that problem."

Gil, Mediawave Festival, 2010: I was saying the revolution takes place in your mind. Once you change your mind and decide that there's something wrong that you want to affect, that's when the revolution takes place. First you have to look at things and decide what you can do. That's when you become revolutionary-- when you see that something's wrong and [you] have to do something about it. It's not all about fighting, it's not all about going to war-- it's about going to war with a problem and deciding how you can affect that problem.

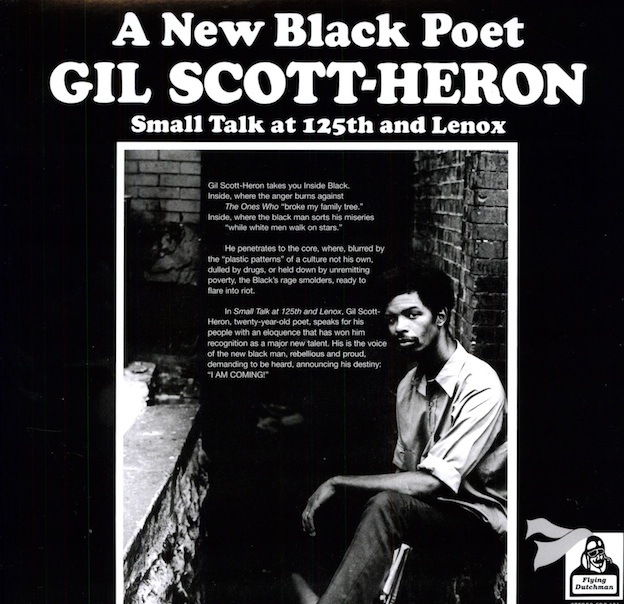

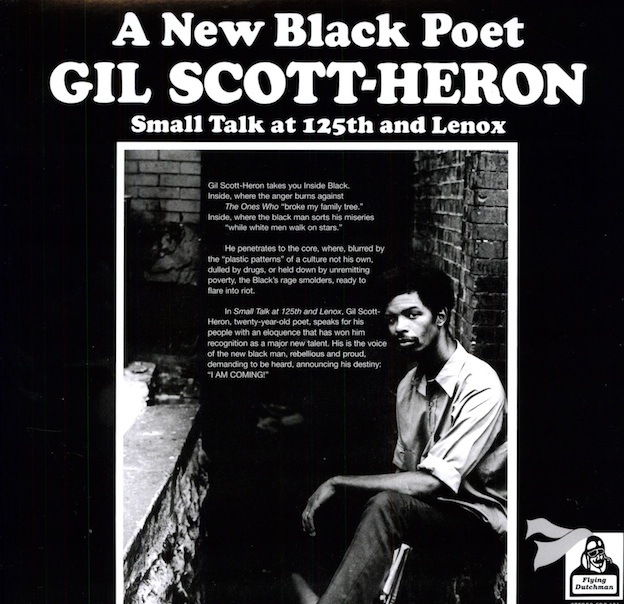

"Revolution" was first recorded as the opening cut on Gil's 1970 debut LP, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. But before that it appeared in the pages of his self-released book of the same name. This was the collection that Gil slipped legendary jazz producer Bob Thiele when he and Brian Jackson were looking for songwriting opportunities. Thiele passed at the time, though, telling Gil, "If you make any money [with poetry], maybe we can get some money together and do an album of music."

"Revolution" was first recorded as the opening cut on Gil's 1970 debut LP, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. But before that it appeared in the pages of his self-released book of the same name. This was the collection that Gil slipped legendary jazz producer Bob Thiele when he and Brian Jackson were looking for songwriting opportunities. Thiele passed at the time, though, telling Gil, "If you make any money [with poetry], maybe we can get some money together and do an album of music."

Small Talk was recorded live on stage with two percussionists. Gil sung and played piano on the record's three fully formed songs and the rest of record was made up of straightforward and mostly intense spoken word in the vein of contemporaries like the Last Poets. (A 1971 Billboard review half-dismissed "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" as "a solid soundalike" of the Harlem collective.) Much of the album orbits a similar tone, but in the same space Gil tends to pull back from anything resembling rage to instead offer a panoramic view of the urban landscape. The songs that follow are all sung in Gil's now-trademark fragile intonation and mostly lean personal rather than political. It's a starkly honest affair with Gil both digging deep inside his own story and drawing out the stories of those around him. His eye for detail is unmatched, as on the title track, where he plays silent observer to conversations at the titular intersection, from dope deals to complaints: "I don't know if the riots is wrong/ But whitey been kicking my ass for too long." There's an underlying hum of concern for the larger societal issues of the day, but Gil tends to focus more specifically on how humans internalize and overcome these struggles.

"A good poet feels what his community feels.

Like if you stub your toe, the rest of your body hurts."

Gil, Jet, 1979: There is a long history of black artists who have not separated their art from their lives. They use their art and their talent as an extension of the community, to reflect the mood, the sensitivity, the circumstances.

Gil, Mediawave Festival, 2010: All of those poems don't just represent me, they represent the people I know and see. Some of them were angry, some of them were upset, some of them were parents, some of them were in love with their children, some of them were trying to get jobs, some of them were working with their jobs, some of them had problems with their women. "Pieces of a Man" is about a son seeing his father who just lost his job. I never saw that [personally], but I saw a friend of mine whose father went a little berserk when he lost his job. "Your Daddy Loves You" is not about anger and hellraising, it's about the fact that sometimes men have so many things on their mind they forget to say, "I love you." You have to show the normalcy of your community to show the humanity of your community. A good poet feels what his community feels. Like if you stub your toe, the rest of your body hurts.

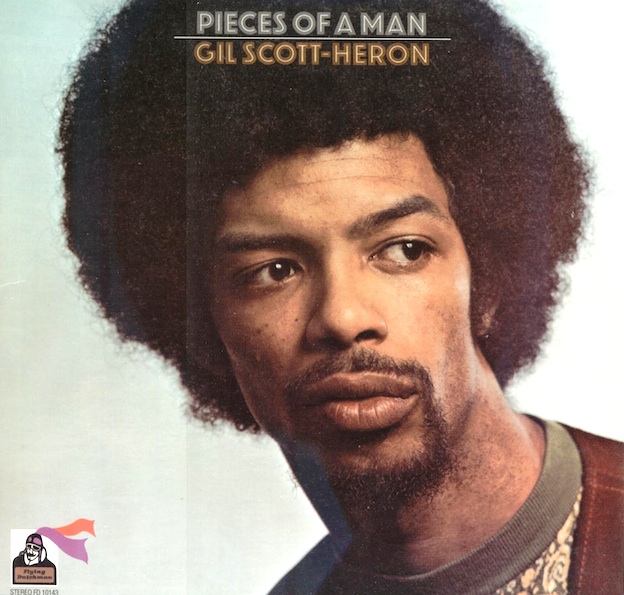

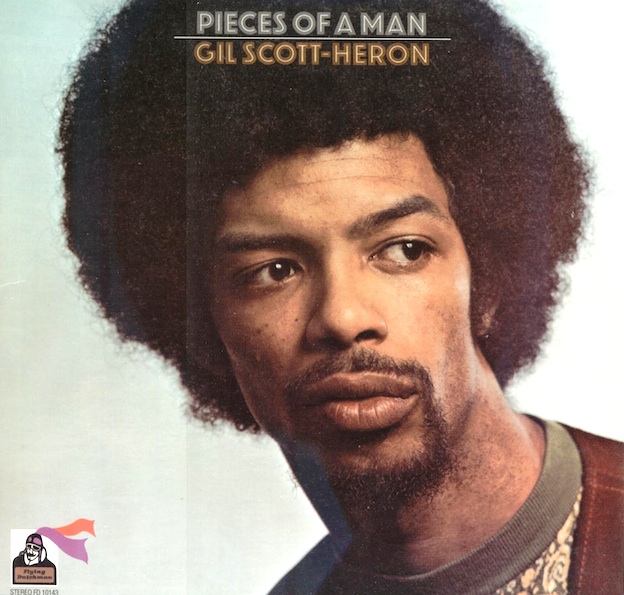

Small Talk made enough money to satisfy Thiele, and for its follow-up Gil returned to the studio to cut Pieces of a Man with a stacked lineup that included heavyweight jazz sessioners Ron Carter, Hubert Laws, and Bernard Purdie as well famed arranger Johnny Pate.

It also served as a full-scale coming-out party for Gil the Singer. While his spoken voice was a powerful vehicle for both the language and political bluster of his time, there's a stark fragility to Gil's singing. Echoing near-contemporaneous Chicagoan influences like Lou Rawls, Oscar Brown Jr., and Terry Callier, Gil delivered his lyrics in a carefully tempered and often melismatic baritone. This is most apparent on 1974's Winter in America, his sparsest collection. Most tracks are backed by little more than hauntingly tinkled solo piano, either acoustic or electric; the record makes a strong case for Gil's voice as the single greatest accompaniment to the Fender Rhodes. As he aged, his instrument turned raspier and even more frail in a way that only magnified his intensity.

Pieces once again opens with "The Revolution", but this time blown out to funk proportions. This would become a common approach for Gil-- his catalog covers a striking amount of ground musically, with songs and styles that would expand and contract over time.

McDonald: He had two main bands. I was part of the Amnesia Express, which he put together when the Midnight Band broke up. We were playing the same songs that the Midnight Band played, but we had a different kind of energy. It was amazing to see how instead of shutting us down, he'd let us play and adopt [our ideas]. When we performed "Angel Dust", it could take up to 40 minutes. It became a performance piece. "Home Is Where the Hatred Is" became "The Other Side", which is a three-part thing on the Spirits album. I was playing "The Other Side" for a couple of years and then one day I went up to my brother and he had a 45 of "The Bottle" and he flipped it over and halfway through the song I said, "Wait a minute, that sounds familiar." It was "Home Is Where the Hatred Is." I had never heard [the studio version of] that song before we started playing it! And we was killing it! He gave us freedom to play.

McDonald: He had two main bands. I was part of the Amnesia Express, which he put together when the Midnight Band broke up. We were playing the same songs that the Midnight Band played, but we had a different kind of energy. It was amazing to see how instead of shutting us down, he'd let us play and adopt [our ideas]. When we performed "Angel Dust", it could take up to 40 minutes. It became a performance piece. "Home Is Where the Hatred Is" became "The Other Side", which is a three-part thing on the Spirits album. I was playing "The Other Side" for a couple of years and then one day I went up to my brother and he had a 45 of "The Bottle" and he flipped it over and halfway through the song I said, "Wait a minute, that sounds familiar." It was "Home Is Where the Hatred Is." I had never heard [the studio version of] that song before we started playing it! And we was killing it! He gave us freedom to play.

Price: Everybody talks about Gil, and Gil was half of it. But Brian [Jackson, Gil's principle collaborator in the first decade of his career] was also the music. Gil was very limited in terms of his musical ability; he could play three chords on the piano. Brian always gets put in the shadows. Had it not been for a lot of Brian's music, I don't know if Gil's work would've been as far reaching-- he reached the jazz community, the R&B community, and then in later years he was a hip-hop influence.

While the hip-hop world, particularly those artists residing on its "conscious rap" shores, embraced Gil Scott-Heron that relationship was not without certain misconceptions, either. It's difficult to find any press from the past 20 years that doesn't explicitly frame Gil as a progenitor to hip-hop. It's equally difficult to find many conversations where he then doesn't explicitly rebuke those comparisons, though usually in good humor.

Gil, BBC's "Hard Talk", 2000: I generally try to put credit where credit is due. For those viewers that go around boom-box bashing-- I am not the one that's responsible. [laughs] For others, I think we came along at a time where there was a transition going on in terms of poetry and music and we were one of the first groups to combine the two... and for that reason I think a lot of people picked up and decided we were the ones who had originated it.

There were parallels to be sure, but to exaggerate them to influence is to overlook the differences of influence. Hip-hop's roots stemmed more directly from radio jocks and reggae toasters, while Gil drew his primary influence from the pages of Harlem Renaissance literature. Gil self-identified as a poet first and foremost (or pianist or "bluesologist"); rapping was simply one of his vehicles. He was a godfather of a bastard child by circumstance. Of course, the parallels helped sustain Gil's later career as many of young listeners (this writer included) came to his music through hip-hop sample sources and incessant name drops, but it's strange and maybe a little disrespectful that someone who was so powerful in his own time is now defined primarily by what came after. Presumably, this is the curse of being ahead of the curve, but this was just one of the many curves he rode along in his career.

Some were more tumultuous than others. 1971's "Home Is Where the Hatred Is", a tale of a struggling heroin addict who describes withdrawal as "turn[ing] your sick soul inside out so that the world can watch you die." The track eerily predicted his own problems with cocaine later in life. Esther Phillips, a recovering heroin addict herself, would later cover the song. In a 1997 interview with Vibe, Gil recalled the songstress' initial response to the record: "She said I knew too much about junkies not to be one." At the time she was wrong, but in the last three decades of his life he would succumb to those very demons. His struggles with substance abuse during this time are well documented, maybe even over-documented-- notably, he smoked crack in front of a New Yorker reporter in 2010.

He didn't record much in this time, effectively retiring after Moving Target in 1982, producing only 1994's inconsistent Spirits and 2010's considerably more consistent Richard Russell-assisted second comeback I'm New Here in the years since. He toured with some regularity during his studio lapses, usually to mixed reviews.

Photo by Mischa Richter

Photo by Mischa Richter

McDonald: In the later years when he wasn't showing up [to shows], I think he thought that by [then] somebody should've come along to pick up [where he left off]. He had carried it all through the 70s and 80s. I guess he just wanted to hang out and do what he wanted to do, but he couldn't get away with it. He was too major. When I joined him he had like 20 albums out! You couldn't really expect someone to operate at that level of excellence for the next 20 or 30 years. He'd burn out. Whatever happened to him or whatever he became, he gave up the office. He didn't want to be bothered talking about all the stuff that was happening today. I figured people needed to leave him alone more than they did. But that was hard because he was so charismatic. It's not that I didn't see his faults; it was just worth it more for me to hang with him and not harass him about that stuff because I was always learning from him.

Leon Collins, housemate: When I look at entertainers in general, most of them are vulnerable, sensitive, compassionate. When trauma impacts them they're emotionally damaged and a lot of them have broken hearts. They self-medicate. That's the history of all music, black music in particular. Michael Jackson's another sensitive soul who was traumatized. I look at Gil as a cultural activist warrior who spoke truth to power and paid a price for it. The demons that chased Gil, he earned them. They were real but I don't think he asked for them.

Larry McDonald, percussionist: There are two Americans I could listen to talk forever: Gil and Richard Pryor. The way they used "black English"-- they could curse and swear and say the most outrageous things, and it didn't seem obscene because it was totally in context.

Larry McDonald, percussionist: There are two Americans I could listen to talk forever: Gil and Richard Pryor. The way they used "black English"-- they could curse and swear and say the most outrageous things, and it didn't seem obscene because it was totally in context. "Revolution" was first recorded as the opening cut on Gil's 1970 debut LP, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. But before that it appeared in the pages of his self-released book of the same name. This was the collection that Gil slipped legendary jazz producer Bob Thiele when he and Brian Jackson were looking for songwriting opportunities. Thiele passed at the time, though,

"Revolution" was first recorded as the opening cut on Gil's 1970 debut LP, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. But before that it appeared in the pages of his self-released book of the same name. This was the collection that Gil slipped legendary jazz producer Bob Thiele when he and Brian Jackson were looking for songwriting opportunities. Thiele passed at the time, though,  McDonald: He had two main bands. I was part of the Amnesia Express, which he put together when the Midnight Band broke up. We were playing the same songs that the Midnight Band played, but we had a different kind of energy. It was amazing to see how instead of shutting us down, he'd let us play and adopt [our ideas]. When we performed "Angel Dust", it could take up to 40 minutes. It became a performance piece.

McDonald: He had two main bands. I was part of the Amnesia Express, which he put together when the Midnight Band broke up. We were playing the same songs that the Midnight Band played, but we had a different kind of energy. It was amazing to see how instead of shutting us down, he'd let us play and adopt [our ideas]. When we performed "Angel Dust", it could take up to 40 minutes. It became a performance piece.