One of Dahomeys' women warriors, with a musket, club, dagger—and her enemy's severed head. From Forbes, Dahomy and the Dahomans (1851).

It is noon on a humid Saturday in the fall of 1861, and a missionary by the name of Francesco Borghero has been summoned to a parade ground in Abomey, the capital of the small West African state of Dahomey. He is seated on one side of a huge, open square right in the center of the town–Dahomey is renowned as a “Black Sparta,” a fiercely militaristic society bent on conquest, whose soldiers strike fear into their enemies all along what is still known as the Slave Coast. The maneuvers begin in the face of a looming downpour, but King Glele is eager to show off the finest unit in his army to his European guest.

As Father Borghero fans himself, 3,000 heavily armed soldiers march into the square and begin a mock assault on a series of defenses designed to represent an enemy capital. The Dahomean troops are a fearsome sight, barefoot and bristling with clubs and knives. A few, known as Reapers, are armed with gleaming three-foot-long straight razors, each wielded two-handed and capable, the priest is told, of slicing a man clean in two.

The soldiers advance in silence, reconnoitering. Their first obstacle is a wall—huge piles of acacia branches bristling with needle-sharp thorns, forming a barricade that stretches nearly 440 yards. The troops rush it furiously, ignoring the wounds that the two-inch-long thorns inflict. After scrambling to the top, they mime hand-to-hand combat with imaginary defenders, fall back, scale the thorn wall a second time, then storm a group of huts and drag a group of cringing “prisoners” to where Glele stands, assessing their performance. The bravest are presented with belts made from acacia thorns. Proud to show themselves impervious to pain, the warriors strap their trophies around their waists.

The general who led the assault appears and gives a lengthy speech, comparing the valor of Dahomey’s warrior elite to that of European troops and suggesting that such equally brave peoples should never be enemies. Borghero listens, but his mind is wandering. He finds the general captivating: “slender but shapely, proud of bearing, but without affectation.” Not too tall, perhaps, nor excessively muscular. But then, of course, the general is a woman, as are all 3,000 of her troops. Father Borghero has been watching the King of Dahomey’s famed corps of “amazons,” as contemporary writers termed them—the only female soldiers in the world who then routinely served as combat troops.

Dahomey–renamed Benin in 1975–showing its location in West Africa. Map: CIA World Factbook.

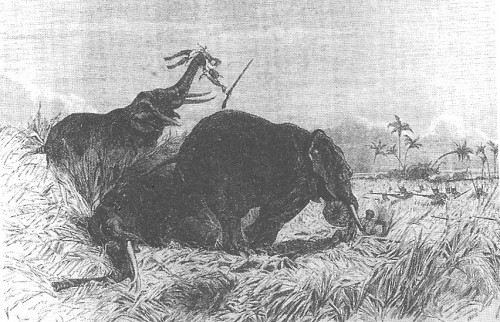

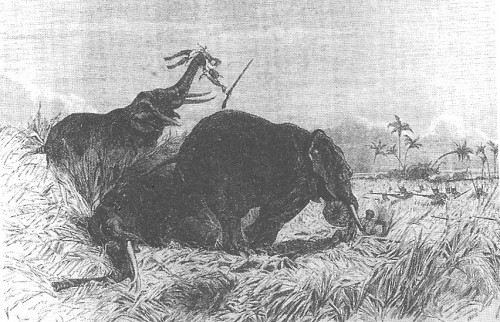

When, or indeed why, Dahomey recruited its first female soldiers is not certain. Stanley Alpern, author of the only full-length Engish-language study of them, suggests it may have been in the 17th century, not long after the kingdom was founded by Dako, a leader of the Fon tribe, around 1625. One theory traces their origins to teams of female hunters known as gbeto, and certainly Dahomey was noted for its women hunters; a French naval surgeon named Repin reported in the 1850s that a group of 20 gbeto had attacked a herd of 40 elephants, killing three at the cost of several hunters gored and trampled. A Dahomean tradition relates that when King Gezo (1818-58) praised their courage, the gbeto cockily replied that “a nice manhunt would suit them even better,” so he drafted them drafted into his army. But Alpern cautions that there is no proof that such an incident occurred, and he prefers an alternate theory that suggests the women warriors came into existence as a palace guard in the 1720s.

Women had the advantage of being permitted in the palace precincts after dark (Dahomean men were not), and a bodyguard may have been formed, Alpern says, from among the king’s “third class” wives–those considered insufficiently beautiful to share his bed and who had not borne children. Contrary to 19th century gossip that portrayed the female soldiers as sexually voracious, Dahomey’s female soldiers were formally married to the king—and since he never actually had relations with any of them, marriage rendered them celibate.

Dahomey's female hunters, the gbeto, attack a herd of elephants.

At least one bit of evidence hints that Alpern is right to date the formation of the female corps to the early 18th century: a French slaver named Jean-Pierre Thibault, who called at the Dahomean port of Ouidah in 1725, described seeing groups of third-rank wives armed with long poles and acting as police. And when, four years later, Dahomey’s women warriors made their first appearance in written history, they were helping to recapture the same port after it fell to a surprise attack by the Yoruba–a much more numerous tribe from the east who would henceforth be the Dahomeans’ chief enemies.

Dahomey’s female troops were not the only martial women of their time. There were at least a few contemporary examples of successful warrior queens, the best-known of whom was probably Nzinga of Matamba, one of the most important figures in 17th-century Angola—a ruler who fought the Portuguese, quaffed the blood of sacrificial victims, and kept a harem of 60 male concubines, whom she dressed in women’s clothes. Nor were female guards unknown; in the mid-19th century, King Mongkut of Siam (the same monarch memorably portrayed in quite a different light by Yul Brynner in The King and I) employed a bodyguard of 400 women. But Mongkut’s guards performed a ceremonial function, and the king could never bear to send them off to war. What made Dahomey’s women warriors unique was that they fought, and frequently died, for king and country. Even the most conservative estimates suggest that, in the course of just four major campaigns in the latter half of the 19th century, they lost at least 6,000 dead, and perhaps as many as 15,000. In their very last battles, against French troops equipped with vastly superior weaponry, about 1,500 women took the field, and only about 50 remained fit for active duty by the end.

King Gezo, who expanded the female corps from around 600 women to as many as 6,000. Picture: Wikicommons.

None of this, of course, explains why this female corps arose only in Dahomey. Historian Robin Law, of the University of Stirling, who has made a study of the subject, dismisses the idea that the Fon viewed men and women as equals in any meaningful sense; women fully trained as warriors, he points out, were thought to “become” men, usually at the moment they disemboweled their first enemy. Perhaps the most persuasive possibility is that the Fon were so badly outnumbered by the enemies who encircled them that Dahomey’s kings were forced to conscript women. The Yoruba alone were about ten times as numerous as the Fon.

Backing for this hypothesis can be found in the writings of Commodore Arthur Eardley Wilmot, a British naval officer who called at Dahomey in 1862 and observed that women heavily outnumbered men in its towns—a phenomenon that he attributed to a combination of military losses and the effects of the slave trade. Around the same time Western visitors to Abomey noticed a sharp jump in the number of female soldiers. Records suggest that there were about 600 women in the Dahomean army from the 1760s until the 1840s—at which point King Gezo expanded the corps to as many as 6,000.

No Dahomean records survive to explain Gezo’s expansion, but it was probably connected to a defeat he suffered at the hands of the Yoruba in 1844. Oral traditions suggest that, angered by Dahomean raids on their villages, an army from a tribal grouping known as the Egba mounted a surprise attack that that came close to capturing Gezo and did seize much of his royal regalia, including the king’s valuable umbrella and his sacred stool. “It has been said that only two amazon ‘companies’ existed before Gezo and that he created six new ones,” Alpern notes. “If so, it probably happened at this time.”

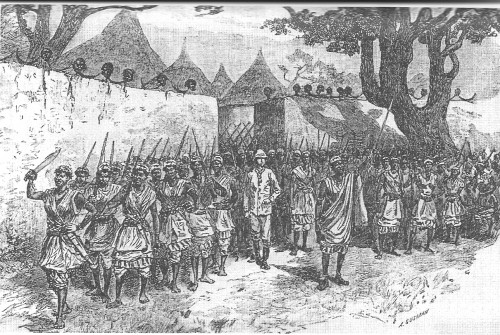

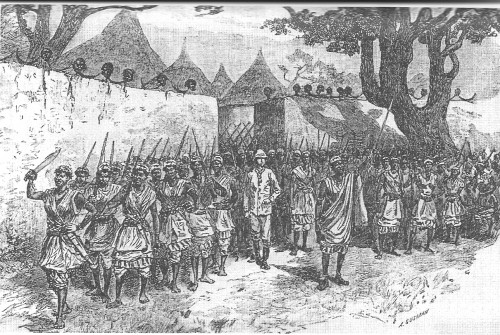

Women warriors parade outside the gates of a Dahomean town, with the severed heads of their defeated foes adorning the walls.

Recruiting women into the Dahomean army was not especially difficult, despite the requirement to climb thorn hedges and risk life and limb in battle. Most West African women lived lives of forced drudgery. Gezo’s female troops lived in his compound and were kept well supplied with tobacco, alcohol and slaves–as many as 50 to each warrior, according to the noted traveler Sir Richard Burton, who visited Dahomey in the 1860s. And “when amazons walked out of the palace,” notes Alpern, “they were preceded by a slave girl carrying a bell. The sound told every male to get out of their path, retire a certain distance, and look the other way.” To even touch these women meant death.

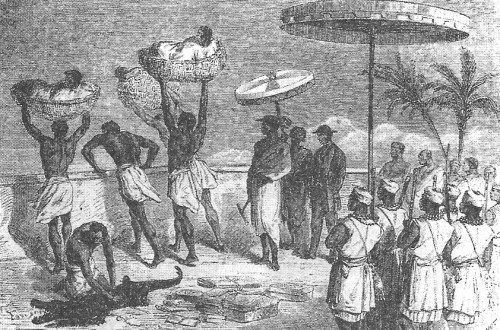

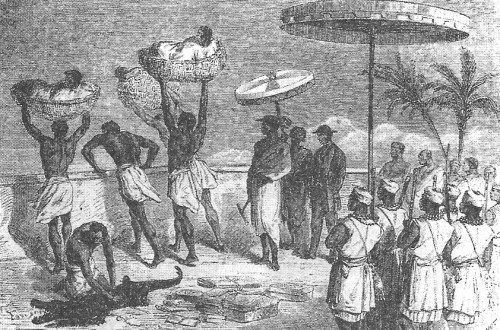

"Insensitivity training": female recruits look on as Dahomean troops hurl bound prisoners of war to a mob below.

While Gezo plotted his revenge against the Egba, his new female recruits were put through extensive training. The scaling of vicious thorn hedges was intended to foster the stoical acceptance of pain, and the women also wrestled one another and undertook survival training, being sent into the forest for up to nine days with minimal rations.

The aspect of Dahomean military custom that attracted most attention from European visitors, however, was “insensitivity training”—exposing unblooded troops to death. At one annual ceremony, new recruits of both sexes were required to mount a platform 16 feet high, pick up baskets containing bound and gagged prisoners of war, and hurl them over the parapet to a baying mob below. There are also accounts of female soldiers being ordered to carry out executions. Jean Bayol, a French naval officer who visited Abomey in December 1889, watched as a teenage recruit, a girl named Nanisca “who had not yet killed anyone,” was tested. Brought before a young prisoner who sat bound in a basket, she:

walked jauntily up to [him], swung her sword three times with both hands, then calmly cut the last flesh that attached the head to the trunk… She then squeezed the blood off her weapon and swallowed it.

It was this fierceness that most unnerved Western observers, and indeed Dahomey’s African enemies. Not everyone agreed on the quality of the Dahomeans’ military preparedness—European observers were disdainful of the way in which the women handled their ancient flintlock muskets, most firing from the hip rather than aiming from the shoulder, but even the French agreed that they “excelled at hand-to-hand combat” and “handled [knives] admirably.”

For the most part, too, the enlarged female corps enjoyed considerable success in Gezo’s endless wars, specializing in pre-dawn attacks on unsuspecting enemy villages. It was only when they were thrown against the Egba capital, Abeokuta, that they tasted defeat. Two furious assaults on the town, in 1851 and 1864, failed dismally, partially because of Dahomean overconfidence, but mostly because Abeokuta was a formidable target—a huge town ringed with mud-brick walls and harboring a population of 50,000.

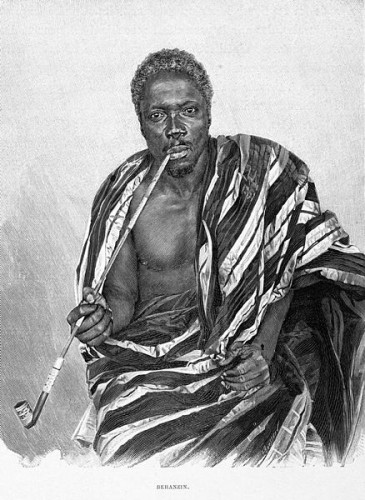

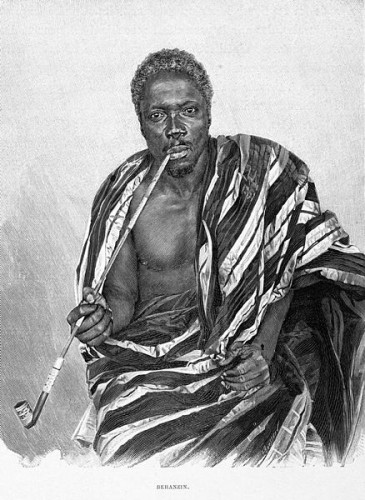

Béhanzin, the last king of an independent Dahomey.

By the late 1870s Dahomey had begun to temper its military ambitions. Most foreign observers suggest that the women’s corps was reduced to 1,500 soldiers at about this time, but attacks on the Yoruba continued. And the corps still existed 20 years later, when the kingdom at last found itself caught up in the “scramble for Africa,” which saw various European powers competing to absorb slices of the continent into their empires. Dahomey fell within the French sphere of influence, and there was already a small French colony at Porto-Novo when, in about 1889, female troops were involved in an incident that resulted in a full-scale war. According to local oral histories, the spark came when the Dahomeans attacked a village under French suzerainty whose chief tried to avert panic by assuring the inhabitants that the tricolor would protect them. “So you like this flag?” the Dahomean general asked when the settlement had been overrun. “Eh bien, it will serve you.” At the general’s signal, one of the women warriors beheaded the chief with one blow of her cutlass and carried his head back to her new king, Béhanzin, wrapped in the French standard.

The First Franco-Dahomean War, which ensued in 1890, resulted in two major battles, one of which took place in heavy rain at dawn outside Cotonou, on the Bight of Benin. Béhanzin’s army, which included female units, assaulted a French stockade but was driven back in hand-to-hand fighting. No quarter was given on either side, and Jean Bayol saw his chief gunner decapitated by a fighter he recognized as Nanisca, the young woman he had met three months earlier in Abomey as she executed a prisoner. Only the sheer firepower of their modern rifles won the day for the French, and in the battle’s aftermath Bayol found Nanisca lying dead. “The cleaver, with its curved blade, engraved with fetish symbols, was attached to her left wrist by a small cord,” he wrote, “and her right hand was clenched around the barrel of her carbine covered with cowries.”

In the uneasy peace that followed, Béhanzin did his best to equip his army with more modern weapons, but the Dahomeans were still no match for the large French force that was assembled to complete the conquest two years later. That seven-week war was fought even more fiercely than the first. There were 23 separate battles, and once again female troops were in the vanguard of Béhanzin’s forces. The women were the last to surrender, and even then—at least according to a rumor common in the French army of occupation—the survivors took their revenge on the French by covertly substituting themselves for Dahomean women who were taken into the enemy stockade. Each allowed herself to be seduced by French officer, waited for him to fall asleep, and then cut his throat with his own bayonet.

A group of women warriors in traditional dress. Picture: Wikicommons.

Their last enemies were full of praise for their courage. A French Foreign Legionnaire named Bern lauded them as “warrioresses… [who] fight with extreme valor, always ahead of the other troops. They are outstandingly brave … well trained for combat and very disciplined.” A French Marine, Henri Morienval, thought them “remarkable for their courage and their ferocity… [they] flung themselves on our bayonets with prodigious bravery.”

Most sources suggest that the last of Dahomey’s women warriors died in the 1940s, but Stanley Alpern disputes this. Pointing out that “a woman who had fought the French in her teens would have been no older than 69 in 1943,” he suggests, more pleasingly, that it is likely one or more survived long enough to see her country regain its independence in 1960. As late as 1978, a Beninese historian encountered an extremely old woman in the village of Kinta who convincingly claimed to have fought against the French in 1892. Her name was Nawi, and she died, aged well over 100, in November 1979. Probably she was the last.

What were they like, these scattered survivors of a storied regiment? Some proud but impoverished, it seems; others married; a few tough and argumentative, well capable, Alpern says, of “beating up men who dared to affront them.” And at least one of them still traumatized by her service, a reminder that some military experiences are universal. A Dahomean who grew up in Cotonou in the 1930s recalled that he regularly tormented an elderly woman he and his friends saw shuffling along the road, bent double by tiredness and age. He confided to the French writer Hélène Almeida-Topor that

one day, one of us throws a stone that hits another stone. The noise resounds, a spark flies. We suddenly see the old woman straighten up. Her face is transfigured. She begins to march proudly… Reaching a wall, she lies down on her belly and crawls on her elbows to get round it. She thinks she is holding a rifle because abruptly she shoulders and fires, then reloads her imaginary arm and fires again, imitating the sound of a salvo. Then she leaps, pounces on an imaginary enemy, rolls on the ground in furious hand-t0-hand combat, flattens the foe. With one hand she seems to pin him to the ground, and with the other stabs him repeatedly. Her cries betray her effort. She makes the gesture of cutting to the quick and stands up brandishing her trophy….

Female officers pictured in 1851, wearing symbolic horns of office on their heads.

She intones a song of victory and dances:

The blood flows,

You are dead.

The blood flows,

We have won.

The blood flows, it flows, it flows.

The blood flows,

The enemy is no more.

But suddenly she stops, dazed. Her body bends, hunches, How old she seems, older than before! She walks away with a hesitant step.

She is a former warrior, an adult explains…. The battles ended years ago, but she continues the war in her head.

Sources

Hélène Almeida-Topor. Les Amazones: Une Armée de Femmes dans l’Afrique Précoloniale. Paris: Editions Rochevignes, 1984; Stanley Alpern. Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2011; Richard Burton. A Mission to Gelele, King of Dahome. London: RKP, 1966; Robin Law. ‘The ‘Amazons’ of Dahomey.’ Paideuma 39 (1993); J.A. Skertchley. Dahomey As It Is: Being a Narrative of Eight Months’ Residence in that Country, with a Full Account of the Notorious Annual Customs… London: Chapman & Hall, 1874.

My development as a feminist was shaped not only by my education at home but also by my education beyond the home. In my college and university training during the 1970s, I was introduced to the work of Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, Jean Toomer, and Alice Walker, all of whom—most especially Walker—had a profound impact upon my development as a feminist. In their work, I discovered theories of resistance and oppression that expanded my developing understanding of gender and the dynamics of male domination and male privilege. A vital work from this period is Walker’sThe Third Life of Grange Copeland, her first novel, one which I read soon after its publication. The reading of this novel was a moment of self-recognition for myself and all the women in my family. The tragedy of Meme and Brownfield Copeland captured what the poet Robert Hayden called in “Those Winter Sundays” the “chronic angers” of our home. Walker’s novel provided a fictional framework for the pivotal event that constituted my initiation into feminism. Above all, it provided a name for the problem that, as Betty Friedan writes in The Feminist Mystique, “has no name.”

My development as a feminist was shaped not only by my education at home but also by my education beyond the home. In my college and university training during the 1970s, I was introduced to the work of Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, Jean Toomer, and Alice Walker, all of whom—most especially Walker—had a profound impact upon my development as a feminist. In their work, I discovered theories of resistance and oppression that expanded my developing understanding of gender and the dynamics of male domination and male privilege. A vital work from this period is Walker’sThe Third Life of Grange Copeland, her first novel, one which I read soon after its publication. The reading of this novel was a moment of self-recognition for myself and all the women in my family. The tragedy of Meme and Brownfield Copeland captured what the poet Robert Hayden called in “Those Winter Sundays” the “chronic angers” of our home. Walker’s novel provided a fictional framework for the pivotal event that constituted my initiation into feminism. Above all, it provided a name for the problem that, as Betty Friedan writes in The Feminist Mystique, “has no name.” As a feminist, I urge all men to embrace this progressive tradition that was advanced by Douglass. Why? Because we cannot, to paraphrase the black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde, dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools. Notwithstanding its appeal of privilege and power, patriarchy is a bankrupt ideology. Based upon the ideology of male superiority and domination, it is antithetical to the historic goals of the black freedom struggle and the story of freedom told in all periods of African American history and literature, most powerfully in the slave narratives. Further, patriarchy blocks the process of self-actualization in men as well as women. It imposes upon men an identity based upon male domination. As an ideology based in privilege and violence, it is corrosive of relationships between men and women, and also those between men. Finally, because of its intolerance of difference, patriarchy is one of the greatest threats to the creation and development of communities, as Toni Morrison has warned us, with her customary acumen and eloquence, in her novel Paradise. The sobering truth at the novel’s center is that if women do not conform to the expectations of men, if they do not submit to the rule of men, the men will kill them. By contrast, feminism is a means of liberating women and men from the ideological trap of patriarchy through the choice of a politics that nurtures a vision of mutuality, equality, democracy, and nonviolence.

As a feminist, I urge all men to embrace this progressive tradition that was advanced by Douglass. Why? Because we cannot, to paraphrase the black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde, dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools. Notwithstanding its appeal of privilege and power, patriarchy is a bankrupt ideology. Based upon the ideology of male superiority and domination, it is antithetical to the historic goals of the black freedom struggle and the story of freedom told in all periods of African American history and literature, most powerfully in the slave narratives. Further, patriarchy blocks the process of self-actualization in men as well as women. It imposes upon men an identity based upon male domination. As an ideology based in privilege and violence, it is corrosive of relationships between men and women, and also those between men. Finally, because of its intolerance of difference, patriarchy is one of the greatest threats to the creation and development of communities, as Toni Morrison has warned us, with her customary acumen and eloquence, in her novel Paradise. The sobering truth at the novel’s center is that if women do not conform to the expectations of men, if they do not submit to the rule of men, the men will kill them. By contrast, feminism is a means of liberating women and men from the ideological trap of patriarchy through the choice of a politics that nurtures a vision of mutuality, equality, democracy, and nonviolence.