Shell in Nigeria: What are the issues?

Contents:

- What is Shell?

- Why Boycott Shell?

The Problem

Environmental Degradation (Natural Gas Flaring, Oil Spills, Pipelines and Construction, Health Impacts)

The "Shell Police"

The trial of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni 8: The Struggle Continues

The Ogoni 20 and others...

Not just the Ogoni!

- Why does the Nigerian government allow this to happen?

- What are groups in Nigeria doing about stopping Shell?

MOSOP demands

Refugees

- What are the United States and other countries doing to stop Shell?

The Commonwealth

The United Nations

The US: words without action

- Sources

Return to Info & Resources

1. What is Shell?

The "Royal Dutch/Shell Group," commonly know as Shell, is an amalgam of over 1,700 companies all over the world. 60% of the Group is owned by Royal Dutch of the Netherlands, and 40% is owned by the Shell Transport and Trading Group of Great Britain. These two companies have worked together since 1903. Shell includes companies like Shell Petroleum of the USA (which wholly owns Shell Oil of the USA and many subsidiaries), Shell Nigeria, Shell Argentina, Shell South Africa, etc.

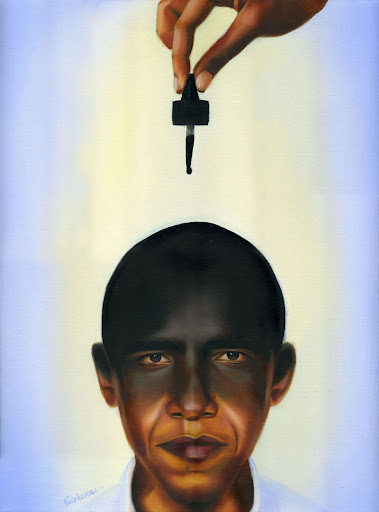

Shell Nigeria is one of the largest oil producers in the Royal Dutch/Shell Group. 80% of the oil extraction in Nigeria is the the Niger Delta, the southeast region of the country. The Delta is home to many small minority ethnic groups, including the Ogoni, all of which suffer egregious exploitation by multinational oil companies, like Shell. Shell provides over 50% of the income keeping the Nigerian dictatorship in power.

Aside from letters, the only way to reach the powers of Shell Nigeria is through other Shell companies like Shell Oil of the USA.

When Shell Oil feels the impact of a boycott and understands that our grievances lie with Shell Nigeria, it puts pressure on the Shell Group to influence change in Nigeria.

2. Why boycott Shell?

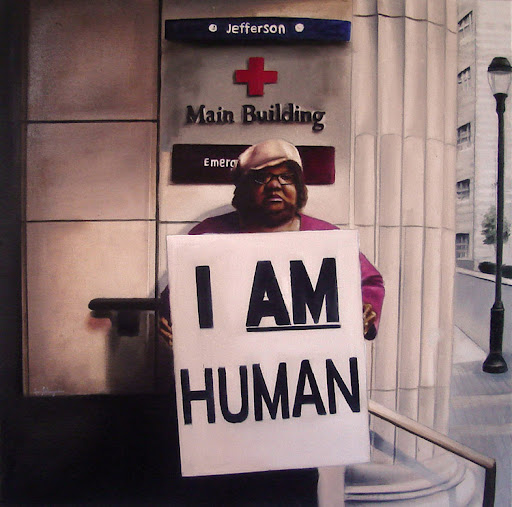

Since the Nigerian government hanged 9 environmental activists in 1995 for speaking out against exploitation by Royal Dutch/Shell and the Nigeria government, outrage has exploded worldwide. The tribunal which convicted the men was part of a joint effort by the government and Shell to suppress a growing movement among the Ogoni people: a movement for environmental justice, for recognition of their human rightsand for economic justice. Shell has brought extreme, irreparable environmental devastation to Ogoniland. Please note that although the case of the Ogoni is the best known of communities in Shell's areas of operation, dozens of other groups suffer the same exploitation of resources and injustices.

The Problem

The most conspicuous aspects of life in contemporary Ogoni are poverty, malnutrition, and disease."

-Ben Naanen, Oil and Socioeconomic Crisis in Nigeria, 1995, pg. 75-6

Although oil from Ogoniland has provided approximately $30 billion to the economy of Nigeria

1, the people of Ogoni see little to nothing from their contribution to Shell's pocketbook. Emanuel Nnadozie, writing of the contributions of oil to the national economy of Nigeria, observed "

Oil is a curse which means only poverty, hunger, disease and exploitation" for those living in oil producing areas

2. Shell has done next to nothing to help Ogoni: by 1996, Shell employed only 88 Ogoni (0.0002% of the Ogoni population, and only 2% of Shell's employees in Nigeria)

3.

Ogoni villages have no clean water, little electricity, few telephones, abysmal health care, and no jobs for displaced farmers and fisher persons, and adding insult to injury, face the effects of unrestrained environmental molestation by Shell everyday.

Environmental Degradation

When crude oil touches the leaf of a yam or cassava, or whatever economic trees we have, it dries immediately, it's so dangerous and somebody who was coming from, say, Shell was arguing with me so I told him that you're an engineer, you have been trained, you went to the university, I did not go to the university, but I know that what you have been saying in the university sleeps with me here so you cannot be more qualified in crude oil than myself who sleeps with crude oil.

-Chief GNK Gininwa of Korokoro, "The Drilling Fields", Glenn Ellis (Director), 1994

Since Shell began drilling oil in Ogoniland in 1958, the people of Ogoniland have had pipelines built across their farmlands and in front of their homes, suffered endemic oil leaks from these very pipelines, been forced to live with the constant flaring of gas. This environmental assault has

smothered land with oil,

killed masses of fish and other aquatic life, and introduced devastating

acid rain to the land of the Ogoni

4. For the Ogoni, a people dependent upon farming and fishing, the poisoning of the land and water has had

devastating economic and health consequences5. Shell claims to clean up its oil spills, but such "clean-ups" consist of techniques like burning the crude which results in a permanent layer of crusted oil meters thick and scooping oil into holes dug in surrounding earth (a temporary solution at best, with the oil flowing out of the hole during the Niger Delta's frequent bouts of rain)

6.

Natural Gas Flaring Ken Saro-Wiwa called gas flaring "the most notorious action" of the Shell and Chevron oil companies

7. In Ogoniland, 95% of extracted natural gas is flared

8 (compared with 0.6% in the United States). It is estimated that the between the CO

2 and methane released by gas flaring, Nigerian oil fields are responsible for more global warming effects than the combined oil fields of the rest of the world

9.

Oil Spills

Although Shell drills oil in 28 countries, 40% of its oil spills worldwide have occurred in the Niger Delta10. In the Niger Delta, there were 2,976 oil spills between 1976 and 199111. In the 1970s spillage totaled more that four times that of the 1989 Exxon Valdez tragedy12. Ogoniland has had severe problems stemming from oil spillage, including water contamination and loss of many valuable animals and plants. A short-lived World Bank investigation found levels of hydrocarbon pollution in water in Ogoniland more than sixty times US limits13 and a 1997 Project Underground survey found petroleum hydrocarbons one Ogoni village's watersource to be 360 times the levels allowed in the European Community, where Shell originates14.

Pipelines and construction

The 12 by 14 mile area that comprises Ogoniland is some of the most densely occupied land in Africa. The extraction of oil has lead to construction of pipelines and facilities on precious farmland and through villages. Shell and its subcontractors compensate landowners with meager amounts unequal to the value of the scarce land, when they pay at all. The military defends Shell's actions with firearms and death: see the Shell Police section below.

Health impacts

The Nigerian Environmental Study Action Team observed increased "discomfort and misery" due to fumes, heat and combustion gases, as well as increased illnesses15. This destruction has not been alleviated by Shell or the government. Owens Wiwa, a physician, has observed higher rates of certain diseases like bronchial asthma, other respiratory diseases, gastro-enteritis and cancer among the people in the area as a result of the oil industry16.

The Shell Police and the Rivers State Internal Security Task Force

Both Shell and the government admit that Shell contributes to the funding of the military in the Delta region. Under the auspices of "protecting" Shell from peaceful demonstrators in the village of Umeuchem (10 miles from Ogoni), the police killed 80 people, destroyed houses and vital crops in 199017. Shell conceded it twice paid the military for going to specific villages. Although it disputes that the purpose of these excursions was to quiet dissent, each of the military missions paid for by Shell resulted in Ogoni fatalities18. The two incidents are a 1993 peaceful demonstration against the destruction of farmland to build pipelines and, later that year, a demonstration in the village of Korokoro19. Shell has also admitted purchasing weapons for the police force who guard its facilities, and there is growing suspicion that Shell funds a much greater portion of the military than previously admitted. In 1994, the military sent permanent security forces into Ogoniland, occupying the once peaceful land. This Rivers State Internal Security Task Force is suspected in the murders of 2000 people20. In a classified memo, its leader described his plans for "psychological tactics of displacement/wasting" and stated that "Shell operations are still impossible unless ruthless military operations are undertaken."21 Since the Task Force occupied Ogoniland in 1994, the Ogoni have lived under constant surveillance and threats of violence. The Nigerian military stepped up its presence in Ogoniland in January of 1997 and again in 1998 before the annual Ogoni Day celebrations.

The trial and execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni 8: The Struggle continues...

Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni 8 were leaders of MOSOP, the Movement for Survival of the Ogoni People. As outspoken environmental and human rights activists, they declared that Shell was not welcome in Ogoniland. On November 10, 1995, they were hanged after a trial by a special military tribunal (whose decisions cannot be appealed) in the murder of four other Ogoni activists. The defendants' lawyers were harassed and denied access to their clients. Although none of them were near the town where the murders occurred, they were convicted and sentenced to death in a trial that many heads of state (including US President Clinton) strongly condemned for a stunning lack of evidence, unmasked partiality towards the prosecution and the haste of the trial. The executions were carried out a mere eight days after the decision. Two witnesses against the MOSOP leaders admitted that Shell and the military bribed them to testify against Ken Saro-Wiwa with promises of money and jobs at Shell20. Ken's final words before his execution were: "The struggle continues!"

The Ogoni 20 and others...

On September 7, 1998, the Ogoni 20 were released on bail! The 20 had been imprisoned for the past four years under the same unsubstantiated charges as those used to execute Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni 8. It is unclear whether they will be tried. Sadly, another 25 people were arrested in January, 1998 for organizing the annual peaceful Ogoni Day celebration. There are unknown other Ogonis imprisoned because they appeared to support the Ogoni cause or for helping others remember Ken Saro-Wiwa.

Not just the Ogoni

The majority of Nigeria's oil comes from the Niger Delta in Southeast Nigeria. All across the Niger Delta, ethnic minority communities suffer the same environmental devastation and oppression under multinational oil companies and the Nigerian military. In 1990, Shell specifically requested that the military protect its facilities from nonviolent protesters in the village of Umeuchem. 80 villagers were killed in two days of violence. A later judiciary panel determined that the villagers posed no threat against Shell21. There have also been accusations of the military arming some communities to fight other communities and prevent the growth of cohesive groups like MOSOP, because wide-spread movements could lead to the end of the flagrant prosperity for Shell and the military. However, communities like the Ijaw, Ekwerre, Oyigba, Ogbia, and others in the Niger Delta have taken measures to reclaim their despoiled lands and human rights22. Since October 1998, Ijaw groups have been occupying oil industry platforms and pipeline transfer stations, at one point blocking a third of Nigeria's oil exports. As of early December, 1988, the groups were still shutting off flow and demanding environmental and economic justice

.

3. Why does the Nigerian government allow this to happen?

In Nigeria, it is questionable whether it is multinational oil companies like Shell or the military which hold ultimate control. Oil companies have a frightening amount of influence upon the government:

80% of Nigerian government revenues come directly from oil, over half of which is from Shell. Countless sums disappear into the pockets of military strongmen in the form of bribes and theft. In 1991 alone, $12 billion in oil funds disappeared (and have yet to be located)23. Local governments admit that oil companies bribe influential local officials to suppress action against the companies. Hence the interests of the Nigerian military regime are clear: to maintain the status quo; to continue acting on Shell's requested attacks on villagers whose farms are destroyed by the oil company; to continue silencing, by any means necessary, those who expose Shell's complete disregard for people, for the environment, for life itself. Shell and the Nigerian military government are united in this continuing violent assault of indigenous peoples and the environment. And just as oil companies exploit numerous communities in the Niger Delta, the government's involvement in the above crimes is not limited to the Ogoni.

To allow the Ogoni to continue raising local and global awareness and pressure would be political suicide for an oppressive, violent military regime, whose only mandate is its own guns24

. The Nigerian military government could not allow this movement of empowerment to spread into other impoverished communities of the Niger Delta. By harassing, wounding and killing Ogoni and others, the military ensures that it remains in power and that its pockets remain lined with the blood money of Delta oil.

4. What are groups in Nigeria doing to stop Shell?

The first highly visible action organized by the Movement for Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) occurred on January 4, 1993 with 300,000 Ogoni (3/5 of the population) participating in the peaceful "Ogoni Day" demonstration. The overwhelming turnout signals a solid consensus for change, for freedom from the oppressions of Shell and the military regime. MOSOP is an umbrella association of ten Ogoni groups encompassing over half of the Ogoni population. Today, MOSOP's leaders live in exile, but MOSOP remains a significant presence both in Nigeria and abroad. Since MOSOP became highly visible, other groups in oil producing regions have begun modeling their actions on MOSOP's tactics of intense yet peaceful demonstrations, pan-ethnic-group organizations, and charters based on the Ogoni Bill of Rights. The military and Shell have been careful to prevent any movements from gaining MOSOP's momentum. See

The MOSOP Story by MOSOP Canada.

There are currently many groups in the Niger Delta working on researching and educating about the environmental and social impacts of the oil industry on the Niger Delta. A few of these are Environmental Rights Action (ERA) and Niger Delta Human and Environmental Rescue Organization (ND-HERO). Additionally, many ethnic groups other than the Ogoni are vocalizing and demonstrating against the environmental racism and human rights abuses of Shell, Chevron, Mobil, and many others.

MOSOP demands

In 1990, MOSOP created the Ogoni Bill of Rights, which outlines the major grievances of the Ogoni, and applies to the peoples of many other oil producing areas. The major points of the Ogoni Bill of Rights are:

- clean up of oil spills

- reduction of gas flaring

- fair compensation for lost land, income, resources, life

- a fair share of profits gained from oil drilled at their expense

- self-determination

Refugees

An oft forgotten element of the Ogoni struggle are the thousands of people who have fled Ogoniland under threat of violence from the Shell Police and the Rivers State Task Force. Ogoni refugees are found in Benin, Togo, and Ghana and other countries

25. A majority of these refugees are students. There are also many people living in exile in the US, Canada and Europe. In 1997,

Diana Wiwa visited Ogoni refugees throughout the region.

5. The UN, the Commonwealth and the US

International condemnation of Nigeria is widespread, but there has been much more talk than action.

The UN

In a surprising and welcome move, the United Nations Special Rapporteur's report on Nigeria (released 4/15/98) accused Nigeria and Shell of abusing human rights and failing to protect the environment in oil producing regions, and called for an investigation into Shell. The report condemned Shell for a "well armed security force which is intermittently employed against protesters." The report was unusual both because of its frankness and its focus on Shell, instead of only on member countries. This was repeated in a November 1998 visit by the same official to Nigeria and the Delta region.

The Commonwealth

The Commonwealth is a group of 53 developed and developing nations around the world. Almost all members have had a past association with another Commonwealth country, as colonies or protectorates or trust territories. The Commonwealth believes in the promotion of international understanding and co-operation, through partnership. Nigeria's membership of the Commonwealth was suspended by Commonwealth Heads of Government on 11 November 1995. Despite repeated pleas from Nigerian human rights activists, the Commonwealth has failed to follow through on threats of expulsion.

The US: words without action

In word, the United States is a strong critic of the Nigerian government, both past and present. It has condemned the existence of the military regime, of election cancellations, and of the situation in Ogoniland. It has threatened to take action. Yet it never does. As the largest consumer of Nigerian oil, the US could be the strongest advocate for human rights and justice, yet it refuses to take on that role. The US government has even protected Nigeria from economic sanctions by states and cities within the US. In March 1998 an official from the Clinton administration warned the Maryland House and Senate that bills creating state-wide economic sanctions against Nigeria for human rights abuses are a violation of US commitments to international trade agreements and to membership in the World Trade Organization. The Clinton administration termed such bills a "threat to the national interest." Not surprisingly, multinational oil companies such as Shell, Mobil, and Chevron lobby heavily against aggressive US policy towards Nigeria, an approach which appears to be working.

Sources: