National Geographic on “Mandela’s Children”

May 18, 2010 · Leave a Comment

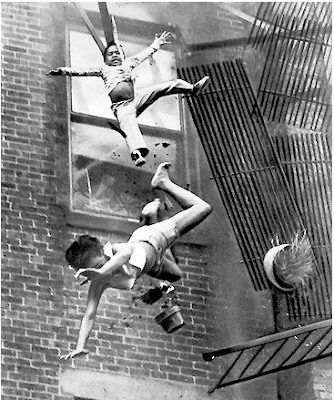

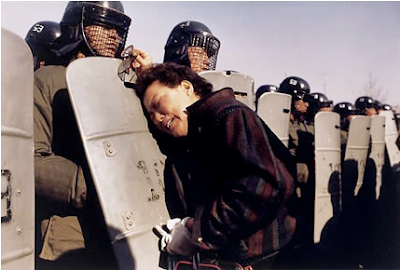

Like many other mainstream publications, National Geographic Magazine’s June 2010 issue (out May 25) will host a feature on South Africa. The feature is entitled, “Mandela’s Children” (titled for Mandela’s comments when he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993: “It will… be measured by the happiness and welfare of the children”) and is completed with photographs by James Nachtwey (see the website for slideshow), and a story by writer Alexandra Fuller.

I’ll just put it out there – I really wanted to dislike this feature.

Typically, the mere sight of that iconic National Geographic golden rectangle irks me to my bones. The publication has a notable history of producing an often times problematic ethnographic lens with which the Western world gazes at the “bizarre” and “different.” That’s why when reviewing the June issue’s South African feature, I immediately–and perhaps unfairly–took a staunch critical mindset. However, as I turned the pages, Fuller’s words, accompanied with Nachtwey’s stunning photographs, slowly melted my skepticism.

Fuller’s story highlights the deeply ingrained sociological, economic, and political problems that still persist in South Africa as a result of apartheid.

The article is a refreshing step above the campy, World Cup-oriented images of South Africa as united and liberated of past divisions. Fuller’s words and Nachtwey’s photographs instead prepare visiting soccer fans for the sights, attitudes, and emotions that they may actually encounter during the games.

Fuller splits the story up into nine sub-headings, each narrative an account of a 1996 shopping mall bombing that injured nearly 70 people and killed four – three of whom were children (all the victims are either coloured or black). The time and place of the bombing, as highlighted by Fuller, is of the utmost importance in order to refute the peaceful Rainbow Nation narrative ala Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu and the TRC.

Two years after the “peaceful” democratic transition to majority rule, and 6 months after the TRC had held a hearing in the small town of Worcester in the Western Cape, racially charged bombs of hatred ripped through the shopping center on Christmas Eve. The murderer, later renamed “military operative” was 19 years old at the time of the bombing and deeply involved in multiple white supremacy organizations that thrived in the country.

Fuller details the various political, emotional, socio-economic, cultural and racial elements that surround the event and lead to the eventual meeting and subsequent forgiveness of the man by his victims. Unlike other countless stories of the same magnitude, this one comes full circle with victim forgiveness and actual restitution.

It’s important to note that organizations aimed for reform and restitution, like the TRC, were limited in their effectiveness – and many stories of torture and political injustice have not been resolved to date.

That’s what I liked about this article. It does a good job of providing a snapshot of the complexity of such things as social and political reform. Unlike what a film like “Invictus” would have us believe, South Africa’s socio-economic landscape and intense disparities are still fueled by racial inequalities – “the long shadow of apartheid.”

The National Geographic feature attempts to break with standard narratives of South Africa as exemplary of equality among people by way of peaceful transition. It does so by pointing out that apartheid’s after-effects live on in the hearts, minds and, in the case of one of the story’s victims, the bodies of many South Africans. This is accomplished through Fuller’s ability to capture the personal drama of each figure in the story. It becomes clear that their drama is not isolated, but is part of a broader contemporary spectrum including everything from violence in the home, influenced by fathers away for months in the gold mines (one of the country’s leading exports), to the recent fraction in the executive national government. And for the pragmatic mind, the feature breaks down the aftermath of apartheid into graphs and charts highlighting the ongoing economic and social inequalities.

The feature–the pictures and the text as a unit–presents South Africa as a hybrid of modernity and tradition, rich and poor, violent and compassionate; in short, an entanglement of realities that while complicated, is certainly not unworthy of the world’s attention next month.

P.S. my sincerest gratitude goes to The Society for getting through an African feature without the single mention of a lion. Thank you.

– Allison Swank

Mandela's Children

South Africa is a vibrant, multiethnic democracy striving, with mixed success, to fulfill its promise. Photojournalist James Nachtwey offers a vision of contemporary life, and Alexandra Fuller tells an intimate story about the long shadow of apartheid.

The Minister

It turns out there is no shortcut, bolt-of-inspiration way to transform a person from layman to minister in the Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa. It takes seven years of rigorous training—seven years of Deon Snyman's youth—which made it all the more distressing when, toward the end of his studies at the University of Pretoria in 1990, Snyman realized he had all the theology a person could possibly need to function in the old South Africa but almost no skills to guide him in the country that had just released Nelson Mandela.

Snyman, who was born and raised in "a traditional Afrikaans family, in a typical Afrikaans town north of Johannesburg," says that back then he knew no black people, had no black friends, had never even had a meaningful conversation with a black person. "The church was divided into white congregations, Coloured congregations, Indian congregations, and black congregations," he says. He decided that the best way he could avoid waking up one morning a foreigner in his own country was to become the minister of a rural, black congregation.