BrennysVideo — May 09, 2010 — Shot with a hidden-cam, this inspirational video shows a member of the Life After Shopping Gospel Choir closing her Chase account and educating employees about the bank's funding of Mountaintop Removal.

What is Mountain Top Removal Mining?

Mountaintop removal / valley fill coal mining (MTR) has been called strip mining on steroids. One author says the process should be more accurately named: mountain range removal. Mountaintop removal /valley fill mining annihilates ecosystems, transforming some of the most biologically diverse temperate forests in the world into biologically barren moonscapes.

Mountaintop removal / valley fill coal mining (MTR) has been called strip mining on steroids. One author says the process should be more accurately named: mountain range removal. Mountaintop removal /valley fill mining annihilates ecosystems, transforming some of the most biologically diverse temperate forests in the world into biologically barren moonscapes.

Download MJ newsletter and fact sheets.

Many thanks to OHVEC for the use of their photographs and assistance in this page.

Steps and Effects

1. Forests are clear-cut; often scraping away topsoil, lumber, understory herbs such as ginseng and goldenseal, and all other forms of life that do not move out of the way quickly enough. Wildlife habitat is destroyed and vegetation loss often leads to floods and landslides. Next, explosives up to 100 times as strong as ones that tore open the Oklahoma City Federal building blast up to 800 feet off mountaintops. Explosions can cause damage to home foundations and wells. “Fly rock,” more aptly named fly boulder, can rain off mountains, endangering resident’s lives and homes.

1. Forests are clear-cut; often scraping away topsoil, lumber, understory herbs such as ginseng and goldenseal, and all other forms of life that do not move out of the way quickly enough. Wildlife habitat is destroyed and vegetation loss often leads to floods and landslides. Next, explosives up to 100 times as strong as ones that tore open the Oklahoma City Federal building blast up to 800 feet off mountaintops. Explosions can cause damage to home foundations and wells. “Fly rock,” more aptly named fly boulder, can rain off mountains, endangering resident’s lives and homes.

2. Huge Shovels dig into the soil and trucks haul it away or push it into adjacent valleys.

2. Huge Shovels dig into the soil and trucks haul it away or push it into adjacent valleys.

3. A dragline digs into the rock to expose the coal. These machines can weigh up to 8 million pounds with a base as big as a gymnasium and as tall as a 20-story building. These machines allow coal companies to hire fewer workers. A small crew can tear apart a mountain in less than a year, working night and day. Coal companies make big profits at the expense of us all.

These machines can weigh up to 8 million pounds with a base as big as a gymnasium and as tall as a 20-story building. These machines allow coal companies to hire fewer workers. A small crew can tear apart a mountain in less than a year, working night and day. Coal companies make big profits at the expense of us all.

4. Giant machines then scoop out the layers of coal, dumping millions of tons of “overburden” – the former mountaintops – into the narrow adjacent valleys, thereby creating valley fills. Coal companies have forever buried over 1,200 miles of biologically crucial Appalachian headwaters streams

4. Giant machines then scoop out the layers of coal, dumping millions of tons of “overburden” – the former mountaintops – into the narrow adjacent valleys, thereby creating valley fills. Coal companies have forever buried over 1,200 miles of biologically crucial Appalachian headwaters streams

5. Coal companies are supposed to reclaim land, but all too often mine sites are left stripped and bare. Even where attempts to replant vegetation have been made, the mountain is never again returned to its healthy state.Reclamation Problems

5. Coal companies are supposed to reclaim land, but all too often mine sites are left stripped and bare. Even where attempts to replant vegetation have been made, the mountain is never again returned to its healthy state.Reclamation Problems

|

Community Impacts Coal washing often results in thousands of gallons of contaminated water that looks like black sludge and contains toxic chemicals and heavy metals. The sludge, or slurry, is often contained behind earthen dams in huge sludge ponds. One of these ponds broke on February 26th, 1972 above the community of Buffalo Creek in southern West Virginia. Pittston Coal Company had been warned that the dam was dangerous, but they did nothing. Heavy rain caused the pond to fill up and it breached the dam, sending a wall of black water into the valley below. Over 132 million gallons of black wastewater raged through the valley. 125 people were killed, 1100 injured and 4000 were left homeless. Over 1000 cars and trucks were destroyed and the disaster did 50 million dollars in damage. The coal company called it an “act of God”.

The school is in lower left of photo. The clear green patch in the lower left is the football field. The tall cylindrical white object is the coal silo, less than 200 feet from the school. The zigzag is the earthen dam holding the sludge lake (2.8 billion gallons), directly above the school. |

Traditional mining communities disappear as jobs diminish and residents are driven away by dust, blasting and increased flooding and dangers from overloaded coal trucks careening down small, windy mountain roads. Mining companies buy many of the homes and tear them down. Dynamite is cheaper than people, so mountaintop removal mining does not create many new jobs.

Mountaintop removal generates huge amounts of waste. While the solid waste becomes valley fills, liquid waste is stored in massive, dangerous coal slurry impoundments, often built in the headwaters of a watershed. The slurry is a witch’s brew of water used to wash the coal for market, carcinogenic chemicals used in the washing process and coal fines (small particles) laden with all the compounds found in coal, including toxic heavy metals such as arsenic and mercury. Frequent blackwater spills from these impoundments choke the life out of streams. One “spill” of 306 million gallons that sent sludge up to fifteen feet thick into resident’s yards and fouled 75 miles of waterways, has been called the southeast’s worst environmental disaster. Of course, it’s not only the people who suffer. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has written that mountaintop removal’s destruction of WV’s vast contiguous forests destroys key nesting habitat for neo-tropical migrant bird populations, and thereby decreases the migratory bird populations throughout the northeast U.S. |

>via: http://www.mountainjusticesummer.org/facts/steps.php

===================================

Mountaintop-removal mining is devastating Appalachia, but residents are fighting back

This article was originally published in Orion Magazine.

Not since the glaciers pushed toward these ridgelines a million years ago have the Appalachian Mountains been as threatened as they are today. But the coal-extraction process decimating this landscape, known as mountaintop removal, has generated little press beyond the region.

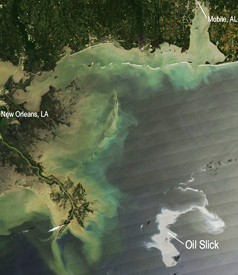

A mountaintop no more.Photo: Vivian Stockman/SouthWings.The problem, in many ways, is one of perspective. From interstates and lowlands, where most communities are clustered, one simply doesn't see what is happening up there. Only from the air can you fully grasp the magnitude of the devastation. If you were to board, say, a small prop plane at Zeb Mountain, Tenn., and follow the spine of the Appalachian Mountains up through Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, you would be struck not by the beauty of a densely forested range older than the Himalayas, but rather by inescapable images of ecological violence. Near Pine Mountain, Ky., you'd see an unfolding series of staggered green hills quickly give way to a wide expanse of gray plateaus pocked with dark craters and huge black ponds filled with a toxic byproduct called coal slurry. The desolation stretches like a long scar up the Kentucky-Virginia line, before eating its way across southern West Virginia.

A mountaintop no more.Photo: Vivian Stockman/SouthWings.The problem, in many ways, is one of perspective. From interstates and lowlands, where most communities are clustered, one simply doesn't see what is happening up there. Only from the air can you fully grasp the magnitude of the devastation. If you were to board, say, a small prop plane at Zeb Mountain, Tenn., and follow the spine of the Appalachian Mountains up through Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, you would be struck not by the beauty of a densely forested range older than the Himalayas, but rather by inescapable images of ecological violence. Near Pine Mountain, Ky., you'd see an unfolding series of staggered green hills quickly give way to a wide expanse of gray plateaus pocked with dark craters and huge black ponds filled with a toxic byproduct called coal slurry. The desolation stretches like a long scar up the Kentucky-Virginia line, before eating its way across southern West Virginia.

Central Appalachia provides much of the country's coal, second only to Wyoming's Powder River Basin. In the United States, 100 tons of coal are extracted every two seconds. Around 70 percent of that coal comes from strip mines, and over the last 20 years, an increasing amount comes from mountaintop-removal sites.

In the name of corporate expedience, coal companies have turned from excavation to simply blasting away the tops of the mountains. To achieve this, they use the same mixture of ammonium nitrate and diesel fuel that Timothy McVeigh employed to level the Murrow Building in Oklahoma City -- except each detonation is 10 times as powerful, and thousands of blasts go off each day across central Appalachia. Hundreds of feet of forest, topsoil, and sandstone -- the coal industry calls all of this "overburden" -- are unearthed so bulldozers and front-end loaders can more easily extract the thin seams of rich, bituminous coal that stretch in horizontal layers throughout these mountains. Almost everything that isn't coal is pushed down into the valleys below. As a result, 6,700 "valley fills" were approved in central Appalachia between 1985 and 2001. The U.S. EPA estimates that over 700 miles of healthy streams have been completely buried by mountaintop removal and thousands more have been damaged. Where there once flowed a highly braided system of headwater streams, now a vast circuitry of haul roads winds through the rubble. From the air, it looks like someone had tried to plot a highway system on the moon.

Seven floods have inundated the town of Bob White, W.Va., since mountaintop-removal mining started in 2000.Photo: Antrim CaskeySerious coal mining has been going on in Appalachia since the turn of the 20th century. But from the time World War II veterans climbed down from tanks and up onto bulldozers, the extractive industries in America have grown more mechanized and more destructive. Ironically, here in Kentucky where I live, coal-related employment has dropped 60 percent in the last 15 years; it takes very few people to run a strip mine operation, with giant machines doing most of the clear-cutting, excavating, loading, and bulldozing of rubble. And all strip mining -- from the most basic truck mine to mountaintop removal -- results in deforestation, flooding, mudslides, and the fouling of headwater streams.

Seven floods have inundated the town of Bob White, W.Va., since mountaintop-removal mining started in 2000.Photo: Antrim CaskeySerious coal mining has been going on in Appalachia since the turn of the 20th century. But from the time World War II veterans climbed down from tanks and up onto bulldozers, the extractive industries in America have grown more mechanized and more destructive. Ironically, here in Kentucky where I live, coal-related employment has dropped 60 percent in the last 15 years; it takes very few people to run a strip mine operation, with giant machines doing most of the clear-cutting, excavating, loading, and bulldozing of rubble. And all strip mining -- from the most basic truck mine to mountaintop removal -- results in deforestation, flooding, mudslides, and the fouling of headwater streams.

Alongside this ecological devastation lies an even more ominous human dimension: an Eastern Kentucky University study found that children in Letcher County, Ky., suffer from an alarmingly high rate of nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and shortness of breath -- symptoms of something called blue baby syndrome -- that can all be traced back to sedimentation and dissolved minerals that have drained from mine sites into nearby streams. Long-term effects may include liver, kidney, and spleen failure, bone damage, and cancers of the digestive tract.

Erica Urias, who lives on Island Creek in Grapevine, Ky., told me she has to bathe her 2-year-old daughter in contaminated water because of the mining around her home. In McRoberts, Ky., the problem is flooding. In 1998, Tampa Energy Company (TECO) started blasting along the ridgetops above McRoberts. Homes shook and foundations cracked. Then TECO sheared off all of the vegetation at the head of Chopping Block Hollow and replaced it with the compacted rubble of a valley fill. In a region prone to flash floods, nothing was left to hold back the rain; this once-forested watershed had been turned into an enormous funnel. In 2002, three so-called hundred-year floods happened in 10 days. Between the blasting and the flooding, the people of McRoberts have been nearly flushed out of their homes.

Related Stories

We Live It Every Day Portraits and words of people on the front line in Appalachian fight against destructive mining practices.The Legend of Weepy Hollow An excerpt from Missing Mountains: We Went to the Mountaintop but It Wasn't ThereConsider the story of Debra and Granville Burke. First the blasting above their house wrecked its foundation. Then the floods came. Four times, they wiped out the Burkes' garden, which the family depended on to get through the winter. Finally, on Christmas morning 2002, Debra Burke took her life. In a letter published in a local paper, her husband wrote: "She left eight letters describing how she loved us all but that our burdens were just getting too much to bear. She had begged for TECO to at least replace our garden, but they just turned their back on her. I look back now and think of all the things I wish I had done differently so that she might still be with us, but mostly I wish that TECO had never started mining above our home."

In the language of economics, Debra Burke's death was an externality -- a cost that simply isn't factored into the price Americans pay for coal. And that is precisely the problem. Last year, American power plants burned over a billion tons of coal, accounting for over 50 percent of this country's electricity use. In Kentucky, 80 percent of the harvested coal is sold and shipped to 22 other states. Yet it is the people of Appalachia who pay the highest price for the rest of the country's cheap energy -- through contaminated water, flooding, cracked foundations and wells, bronchial problems related to breathing coal dust, and roads that have been torn up and turned deadly by speeding coal trucks. Why should large cities like Phoenix and Detroit get the coal but be held accountable for none of the environmental consequences of its extraction? And why is a Tampa-based energy company -- or Peabody Coal in St. Louis, or Massey Energy in Richmond, Va. -- allowed to destroy communities throughout Appalachia? As my friend and teacher the late Guy Davenport once wrote, "Distance negates responsibility."

The specific injustice that had drawn together a group of activists calling themselves the Mountain Justice Summer movement was the violent death of 3-year-old Jeremy Davidson. At 2:30 in the morning on Aug. 30, 2004, a bulldozer, operating without a permit above the Davidsons' home, dislodged a thousand-pound boulder from a mountaintop-removal site in the town of Appalachia, Va. The boulder rolled 200 feet down the mountain before it crushed to death the sleeping child.

But Davidson's death is hardly an isolated incident. In West Virginia, 14 people drowned in the last three years because of floods and mudslides caused by mountaintop removal, and in Kentucky, 50 people have been killed and over 500 injured in the last five years by coal trucks, almost all of which were illegally overloaded.

What\'s left of Kayford Mountain, W.Va.Photo: Antrim Caskey

What\'s left of Kayford Mountain, W.Va.Photo: Antrim Caskey

Fighting for Their Lives

On the third of July, I drove across 10,000 acres of boulder-strewn wasteland that used to be Kayford Mountain, W.Va. -- one of the most hideous mountaintop-removal sites I've seen. But right in the middle of the destruction, rising like a last gasp, is a small knoll of untouched forest. Larry Gibson's family has lived on Kayford Mountain for 200 years. And most of his relatives are buried in the family cemetery, where almost every day Gibson has to clear away debris known as "flyrock" from the nearby blasting.

Last year, Kenneth Cane, the great-grandson of Crazy Horse, came to this cemetery. Surrounded by Gibson and his kin, Cane led a prayer vigil. Then he turned to Gibson, put a hand on his shoulder, and said, "How does it feel to lose your land?"

"What was I going to say to him?" Gibson asked me, sitting at the kitchen table of his small, two-room cabin beneath a single, solar-powered fluorescent bulb. Certainly an Oglala Lakota heir would know something about having mountains stolen away by people in search of valuable minerals.

A short, muscular man, Gibson is easily given to emotion when he starts talking about his home place -- both what remains of it and what has been destroyed. Forty seams of coal lie beneath his 50 acres. Gibson could be a millionaire many times over, but because he refuses to sell, he has been shot at and run off his own road. One of his dogs was shot and another hanged. A month after my visit, someone sabotaged his solar panels. In 2000, Gibson walked out onto his porch one day to find two men dressed in camouflage, approaching with gas cans. They backed away and drove off, but not before they set fire to an empty cabin that belongs to one of Gibson's cousins. This much at least can be said for the West Virginia coal industry: it has perfected the art of intimidation.

Gibson knows he isn't safe. "This land is worth $450 million," he told me, "so what kind of chances do I have?" But he hasn't backed down. He travels the country telling his story and has been arrested repeatedly for various acts of civil disobedience. When Gibson talks to student groups, he asks them, "What do you hold so dear that you don't have a price on it? And when somebody comes to take it, what will you do? For me, it's this mountain and the memories I had here as a kid. It was a hard life, but here I was equal to everybody. I didn't know I was poor until I went to the city and people told me I was. Here I was rich."

A coal silo looms behind Marsh Fork Elementary School.Photo: Antrim CaskeyJust down the mountain from Gibson's home, in the town of Rock Creek, stands the Marsh Fork Elementary School. Back in 2004,Ed Wiley, a 47-year-old West Virginian who spent years working on strip mines, was called by the school to come pick up his granddaughter Kayla because she was sick. "She had a real bad color to her," Wiley told me. The next day the school called again because Kayla was ill, and the day after that. Wiley started flipping through the sign-out book and found that 15 to 20 students went home sick every day because of asthma problems, severe headaches, blisters in their mouths, constant runny noses, and nausea. In May 2005, when Mountain Justice volunteers started going door-to-door in an effort to identify citizens' concerns and possibly locate cancer clusters, West Virginia activist Bo Webb found that 80 percent of parents said their children came home from school with a variety of illnesses. The school, a small brick building, sits almost directly beneath a Massey Energy subsidiary's processing plant where coal is washed and stored. Coal dust settles like pollen over the playground. Nearly 3 billion gallons of coal slurry, which contains extremely high levels of mercury, cadmium, and nickel, are stored behind a 385-foot-high earthen dam right above the school.

A coal silo looms behind Marsh Fork Elementary School.Photo: Antrim CaskeyJust down the mountain from Gibson's home, in the town of Rock Creek, stands the Marsh Fork Elementary School. Back in 2004,Ed Wiley, a 47-year-old West Virginian who spent years working on strip mines, was called by the school to come pick up his granddaughter Kayla because she was sick. "She had a real bad color to her," Wiley told me. The next day the school called again because Kayla was ill, and the day after that. Wiley started flipping through the sign-out book and found that 15 to 20 students went home sick every day because of asthma problems, severe headaches, blisters in their mouths, constant runny noses, and nausea. In May 2005, when Mountain Justice volunteers started going door-to-door in an effort to identify citizens' concerns and possibly locate cancer clusters, West Virginia activist Bo Webb found that 80 percent of parents said their children came home from school with a variety of illnesses. The school, a small brick building, sits almost directly beneath a Massey Energy subsidiary's processing plant where coal is washed and stored. Coal dust settles like pollen over the playground. Nearly 3 billion gallons of coal slurry, which contains extremely high levels of mercury, cadmium, and nickel, are stored behind a 385-foot-high earthen dam right above the school.

In 1972, a similar coal impoundment dam collapsed at Buffalo Creek, W.Va., killing 125 people. Two hundred and eighty children attend the Marsh Fork Elementary School. It is unnerving to imagine what damage a minor earthquake, a heavy flash flood, or a structural failure might do to this small community. And according to documents that longtime activist Julia Bonds obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, the pond is leaking into the creek and groundwater around the school. Students often cannot drink from the water fountains. And when they return from recess, their tennis shoes are covered with black coal dust.

Massey responded to complaints about the plant by applying for a permit to enlarge it, with a new silo to be built even closer to the school. It was this callousness that led to the first major Mountain Justice direct action on the last day of May 2005. About a hundred out-of-state activists, alongside another hundred local citizens, gathered at the school and marched next door to the Massey plant.

Inez Gallimore, an 82-year-old woman whose granddaughter attended the elementary school, walked up to the security guard and asked for the plant superintendent to come down and accept a copy of the group's demands that Massey shut down the plant. When the superintendent refused, Gallimore sat down in the middle of the road, blocking trucks from entering or leaving the facility. When police came to arrest her, they had to help Gallimore to her feet, but not before TV cameras recorded her calling Massey Energy a "terrorist organization."

Activists protest peacefully outside a coal-processing plant in West Virginia.Photo: Antrim CaskeyThree other protesters took the woman's place and were arrested. Three more followed.

Activists protest peacefully outside a coal-processing plant in West Virginia.Photo: Antrim CaskeyThree other protesters took the woman's place and were arrested. Three more followed.

In the end, the media coverage at the Marsh Fork rally prompted West Virginia Gov. Joe Manchin (D) to promise he would put together an investigative team to look into the citizens' concerns. But seven days after that promise, on June 30, Massey received its permit to expand the plant.

An Ugly History

The history of resource exploitation in Appalachia, like the history of racial oppression in the South, follows a sinister logic -- keep people poor and scared so that they remain powerless. In the 19th century, mountain families were actually doing fairly well farming rich bottomlands. But populations grew, farms were subdivided, and then northern coal and steel companies started buying up much of the land, hungry for the resources that lay below. By the time the railroads reached headwater hollows like McRoberts, Ky., men had little choice but to sell their labor cheaply, live in company towns, and shop in overpriced company stores. "Though he might revert on occasion to his ancestral agriculture," wrote coal field historian Harry Caudill, "he would never again free himself from dependence upon his new overlords." In nearly every county across central Appalachia, King Coal had gained control of the economy, the local government, and the land.

In the decades that followed, less obvious tactics kept Harlan County one of the poorest places in Appalachia. Activist Teri Blanton, whose father and brother were Harlan County miners, has spent many years trying to understand the patterns of oppression that hold the Harlan County high-school graduation rate at 59 percent and the median household income at $18,665. "We were fueling the whole United States with coal," she said of the last hundred years in eastern Kentucky. "And yet our pay was lousy, our education was lousy, and they destroyed our environment. As long as you have a polluted community, no other industry is going to locate there. Did they keep us uneducated because it was easier to control us then? Did they keep other industries out because then they can keep our wages low? Was it all by design?"

Whether one detects motive or not, this much is clear: 41 years after Lyndon Johnson stood on a miner's porch in adjacent Martin County and announced his War on Poverty, the poverty rate in central and southern Appalachia stands at 30 percent, right where it did in 1964. What's more, maps generated by the Appalachian Regional Commission show that the poorest counties -- those colored deep red for "distressed" -- are those that have seen the most severe strip mining and the most intense mountaintop removal.

There is a galling irony in the fact that the 14th Amendment, which was designed to protect the civil liberties of recently freed African slaves, was later interpreted in such a way as to give corporations like Massey all of the rights of "legal persons," while requiring little of the accountability that we expect of individuals. Because coal companies are not individuals, they often operate without the moral compass that would prevent a person from contaminating a neighbor's well, poisoning the town's drinking water, or covering the local school with coal dust. This situation is compounded by federal officials who often appear more loyal to corporations than to citizens. Consider the case of Jack Spadaro, a whistle-blowerwho was forced out of his job at the U.S. Department of Labor's Mine Safety and Health Administration precisely because he tried to do his job -- protecting the public from mining disasters.

When the Buffalo Creek dam in West Virginia broke in 1972, Spadaro, a young mining engineer at the time, was brought in to investigate. He found that the flood could have been prevented by better dam construction, and he spent the next 30 years of his career at MSHA investigating impoundment dams. So when a 300-million-gallon slurry pond collapsed in Martin County, Ky., in 2000, causing one of the worst environmental disasters this side of the Mississippi, Spadaro was again named to the investigating team. What he found was that Massey had known for 10 years that the pond was going to break. Spadaro wanted to charge Massey with criminal negligence.

There was only one problem. Elaine Chao, Spadaro's boss at the Department of Labor, is also Kentucky Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell's wife; and it is McConnell, more than anyone else in the Senate, who advocates that corporations are persons that, as such, can contribute as much money as they want to electoral campaigns. It turns out that Massey had donated $100,000 to a campaign committee headed by McConnell. Not surprisingly, Spadaro got nowhere with his charges. Instead, someone changed the lock on his office door and he was placed on administrative leave.