Gil Scott-Heron f. Nas, “New York is Killing Me (1200Squad Remix)” MP3

- story Peter Macia

- photo Gabriele Stabile (FADER #66)

Gil Scott-Heron’s new album I’m New Here is full of dark and foreboding tales that make his home city sounds like an apocalypse epicenter, but add Nasty Nas to the mix actually talking about the apocalypse and numerology, as is one of his specialties, and you’ve got one of the more epic New York matchups of all time. As you may have guessed, Scott-Heron and Nas’ pops, Olu Dara, are acquainted, so there’s history there, too. Basically, if you’ve never been to the Big Apple and want to know what it feels like to live here on not the best of days, “New York is Killing Me” is all you need.

Download: Gil Scott-Heron f. Nas, “New York is Killing Me (Remix)”

New Book: Climbin' Jacob's Ladder

Climbin' Jacob's Ladder

Climbin' Jacob's Ladder

The Black Freedom Movement Writings of Jack O'Dell

Edited and Introduced by Nikhil Pal Singh

A George Gund Foundation Book in African American Studies

University of California PressDescription:

This book collects for the first time the black freedom movement writings of Jack O'Dell and restores one of the great unsung heroes of the civil rights movement to his rightful place in the historical record. Climbin' Jacob's Ladder puts O'Dell's historically significant essays in context and reveals how he helped shape the civil rights movement. From his early years in the 1940s National Maritime Union, to his pioneering work in the early 1960s with Martin Luther King Jr., to his international efforts for the Rainbow Coalition during the 1980s, O'Dell was instrumental in the development of the intellectual vision and the institutions that underpinned several decades of anti-racist struggle. He was a member of the outlawed Communist Party in the 1950s and endured red-baiting throughout his long social justice career. This volume is edited by Nikhil Pal Singh and includes a lengthy introduction based on interviews he conducted with O'Dell on his early life and later experiences. Climbin' Jacob's Ladder provides readers with a firm grasp of the civil rights movement's left wing, which O'Dell represents, and illuminates a more radical and global account of twentieth-century US history.

Reviews:

"This book helps to set the record straight, not just through the facts of O'Dell's life, but through introducing the reader to O'Dell's powerful analysis."—Bill Fletcher Jr., coauthor of Solidarity Divided

"Jack O'Dell describes an 'easy journey…[and] an easy course' through his extraordinary life. But there was and is nothing easy about the roles Jack played—and continues to play—as strategist, tactician, mentor, and leader in so many campaigns for justice. As often behind the scenes as in front of the microphone, Jack fought for internationalism in the African-American freedom movement and held the internationalist movement accountable for fighting racism. Jack O'Dell resides among the greats in the pantheon of our movements and of our country. His words continue to shape our history."—Phyllis Bennis, author of Challenging Empire: How People, Governments and the UN Defy U.S. Power

"Jack O'Dell is one of the great unsung heroes of the Black Freedom Movement. Climbin' Jacob's Ladder offers a fascinating and inspiring chronicle of O'Dell's long career through his own writings. With a brilliant and exhaustive introduction by Nikhil Singh, one of the sharpest radical thinkers of his generation, this collection is a vital addendum and corrective to our existing knowledge of the 'long' Civil Rights Movement and its legacy."—Barbara Ransby, author of Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision

VIDEO:Florida’s “Modern Day Slavery”

Follow the story of Joseph Dieune, a Haitian migrant worker who visited the United States to make money for his family back home.Learn about issues of discrimination against illegal immigrants and explore the life of a small agricultural center located just south of the city of Miami.

By Paul Franz, Graduate Student of Multimedia at the University of Miami School of Communication and the Knight Center for International Media // Coral Gables, FL

Source: Seraphicx

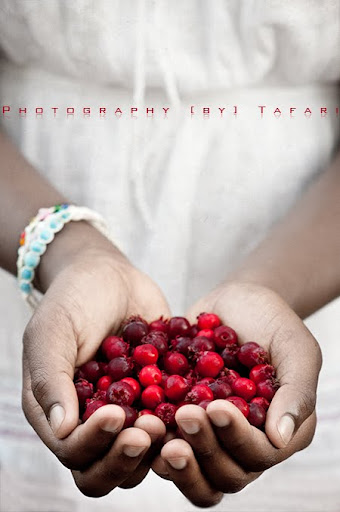

Interview: Tafari Stevenson-Howard :: Photographer

How did you discover photography? I discovered my love for picture taking in my teens when I became the family “picture taker” and photo archivist. Today I still have photos that family members want but I refuse to give them up. More recently, I became excited about the art of photography after my cousin & photography mentor Verlisa McNair-Allen encouraged me to get my first DSLR about 4 years ago.

After I decided to make the purchase of my DSLR, the rest was history! My love for taking pictures quickly developed into a passion for making photographic art and telling stories through the lens.How is your ethnicity a source of inspiration or strength in your work? Or is it just sort of a default setting that has little bearing. My ethnicity is a secondary factor when it comes to my artistic vision but I will say that I find so much beauty in my people that I love to capture. Even things like a man’s ashy & rough blue-black hands have a story to tell.Tell us about the challenges of being a photographer. One of my challenges is staying motivated in the winter months here in Michigan. I love getting out and about to photograph on the streets but the snow, cold temperatures & drab colors of Michigan winters take a toll on my creative soul. To help combat this, I work on indoor projects that help fill my needs, such as my food series. (http://mindspill.bygbaby.com/category/bygfood)

Other more universal challenges that I face are keeping up with software & equipment technologies. Seems like I’m constantly trying to stay on top of the latest & greatest so that I can stay relevant. And one of the largest challenges that I & many other photographers face is the continual decline of client photo budgets.

With so many young inexperienced photographers on the scene offering prices at a fraction of a real rate, it’s hard to compete. Especially when clients are looking for more but want to pay less. I have had to walk away from quite a few jobs because of this.

What aspect of photography do you really love? I LOVE macro photography with all of my heart! Specifically speaking, macro floral photography is where it’s at for me! I see my floral macro images as offering an inside look into hidden elements of a subject that is not fully understood or appreciated for its intricacies.What's your dream job/project? My dream project is such a cliché yet it is my desire! I would love to travel to Brazil (São Paulo, Bahia, Brasilia, Salvador) to photograph & document the lives of my people. Life from the favelas to the beaches to the boardroom.

It is known that Brazil has the largest population of Black people in the world outside of the continent of Africa & I have a strong desire to see what life is like there myself so that I can share with the rest of the world.

Know any sponsors???Can you discuss any specifics about the process of creating a few of the pieces you sent.

“Dark Berries” – The service berries presented here are actually grown at my home. My goal was to have soft and muted colors with the exception of the berries, which I wanted to basically pop off the screen or print. After we finished a few shots, we enjoyed the berries.

"Black Is Beautiful" - I incorporated a continuous shutter while dropping a rubber ball into the cup of coffee. It took me about 4 tries to get a result that I was happy with but I had fun while doing so. And yes, it was a mess!!!

“So Pink, So Juicy, So Delicious I” – This photo shows a red powder puff flower which I photographed with a 105mm macro lens, which was about 12 inches. When in the hand, you cannot see the pollen at the end of the petals but thanks to the magic of a good macro lens, those hidden details come out for an impressive show.

“Caribana Blue“ A random street scene taken at the 2008 Toronto Caribana parade. This image represents how mistakes can sometimes turn to gold. The sun was so bright and I had forgotten my sunglasses & could barely see my camera settings, so I kinda fudged my way through some shots & wound up with some fun & brightly colored images. I guess I can say that this is one mistakes that paid off.Lastly, two consistent themes in my images are color & light. The color must be rich & attention grabbing. The light must be perfect & I have a preference for ambient/available light.

Any advice for neophytes?

1. Learn to live without using your camera’s automated settings such as shutter & aperture priority. Photographing in manual mode gives you greater control!!!

Once I got out of my comfort zone & into manual mode, I discovered so much more & my images became more creative as I was able to control how my subjects would be photographed.

2. Seek out a photography mentor in your community. Learning on your own works in most cases but there is nothing like learning from someone who has been in your shoes.

3. Open a Flickr account!!! Over the past few years, I have leaned so much from participating with Flickr. There you can find creative inspiration, seasoned technical knowledge & an audience for your work that can help you grow with critical feedback.

4. A camera is a camera, don’t get caught up into having to have a Sony, Nikon Canon etc. Get a camera that feels right for you. And once you have that camera, please invest into a 50mm f/1.4 lens. It will save your life. Trust me on that!

Inside a Divided Upper East Side Public School

Whites in the front door, blacks in the back door

By Steven Thrasher

published: February 23, 2010

If you're a white student and you arrive at the public elementary school building on 95th Street and Third Avenue, you'll probably walk through the front door. If you're a black student, you'll probably come in through the back.It's a very New York kind of school facility: two completely different elementary schools sharing the same space.

The boxy, utilitarian structure was built in 1959 to house P.S.198, named after Isador and Ida Straus to commemorate the Congressman and Macy's department store owner and his wife, who both died in the 1912 sinking of the Titanic.

Since 1988, the building has shared space with another school, in a tradition that has rapidly increased under the reformist scheme of Mayor Mike Bloomberg.

In this case, it's the Lower Laboratory School for Gifted Education (P.S.77) that has been given space in the old Straus building—including the part that contains the front door.

Lower Lab is mostly composed of white students (69 percent) and Asian children, who are driven in from all over Manhattan.

Straus is zoned, which means it has to serve any child from the local neighborhood. For that reason, it's overwhelmingly Latino (47 percent) and black (24 percent).

Over the main entrance, the old sign for Straus remains, but Straus kids are told to go around to the back of the building.

Even Straus staff members are instructed by the NYPD School Safety Agent at the front door to use the rear entrance.

An African-American attorney, Granville Leo Stevens, who showed up at the front door recently on official Straus business, says he was only "grudgingly" allowed to enter the front door after he complained to the SS agent.

"It's the craziest thing I've ever seen," Stevens says.

The only people welcomed openly to the front entrance of the schoolhouse are very young kids with killer testing skills.

Lower Lab is designated as talented and gifted, and it's open throughout the Department of Education's District 2—which includes all of the Upper East Side and much of Manhattan south of Central Park—but only to youngsters who score high on tests given to them at four years of age.

In return for the high marks, the privileged kids of Lower Lab not only never have to sit in classes with the Straus children, they don't even have to mix with them on the way to school.

By 8 a.m., except for a few stragglers, the local kids walking on their way to Straus—some holding hands with parents—have all trudged up 95th Street, entered a gate, crossed a schoolyard, and disappeared into the back entrance of the building.

And that's when the other kids start showing up. Classes for Lower Lab start later—at 8:30—so at about 8 a.m., the automobiles start to arrive: Black Mercedes sedans, town cars, and taxis pull up to the curb at the front door, depositing white children onto the sidewalk. At one point, on a recent morning, there were so many black SUVs backed up that it looked like a head of state was stopping by before heading to the U.N.

Lower Lab parents often get out of their cars to walk their children the last few feet to the front door. Mom and Dad wear well-tailored jackets and suits. Several children's coats are adorned with lift tags, suggesting a weekend ski trip. And many of the Lower Lab kids arrive with musical instruments slung over their shoulders. (Lower Lab has an instrumental musical education program; Straus does not.)

Inside, the building is not divided neatly in half for the two schools. They share floors, and a Lower Lab classroom might sit right next to a Straus classroom.

There are areas that both schools share. In these spaces—hallways, for example—an emphasis has been placed on harmony: The hallways have been given names like "Respect Avenue," "Understanding Street," and "Unity Avenue."

Except for these nods to cooperation, you see signs of the division between the two schools everywhere. In a hallway, on a recent morning, there was a five-gallon water bottle for soliciting funds for Haiti disaster relief—but only from Straus people. A large bulletin board reads, "We are All Connected," and graphically connects pictures of all the teachers, assistants, and administrators—of just Lower Lab.

On a wall of "Golden Rule Avenue," there's a display of "position papers" written by a class of Straus fifth-graders. The illustrated title pages demonstrate how earnest 10-year-olds can be.

"Eat Healthy! It's good for you."

"The Damaging Effects of Alcohol."

Another, "No Smoking!," features the declaration that smoking "Damages teeth! Damages chin! [Makes a] Hole in throat! [Makes you] Lose fingers!" It's accompanied by matching drawings of finger amputation, face mutilation, and even a tracheotomy—the horrors of each rendered for maximum effect in the hand of a child using Magic Marker.

If only these earnest young moralizers were so passionate about classroom order.

"They are good children, they really are," a fifth-grade Straus teacher says as she fights a continuing battle to keep things under control. "But I have to get them to listen," she adds, her voice rising as she turns back toward her chattering flock, giving them the evil eye.

Throughout Straus, the biggest challenge of having almost 30 kids in a room seems to be controlling the chaos. Over a 40-minute period, a science teacher was observed asking her children more than 30 times to quiet down as she tried to teach a lesson about earthquakes. She scolded them and gave them disapproving looks. The students responded by staring at the floor, looking ashamed (or at least pretending to be).

Seconds later, some students tuned out the earthquake lesson and began a discussion of Nintendo DS.

The modern elementary school classroom doesn't really seem to help the situation. Gone are the rows of individual desks of yesteryear. Today's classrooms look more like the kindergartens of the past, with children sitting on carpeting or together at large tables. It's all very conducive to chatty conversation and not paying attention. The students of Straus spend nearly the entire day in groups on the floor or huddled together at tables with friends.

In this particular class, most of the students are Latino and black, and a few are recent arrivals from China. There's one white kid—and she seems utterly oblivious of her minority status.

The teacher is a stern woman whose commute can last up to two hours each way. Teaching is her second career, and she obviously has a love for it.

In the middle of a lesson, her students' chatter gets too loud. She stops speaking, and turns off the lights. First, she admonishes "those of you who don't want to learn, who are holding others back." Then she calls out another equally disruptive group: "For those of you who think you're all that, may I remind you that you still have something to learn."

In the constant battle, the teacher is always fighting on two fronts: There are those who talk because they're poor students and can't sit still in a classroom, and then there are those who interrupt because they're smart and bored.

One student from the latter group—we'll call her "Doreen"—can be as distracting as one of the troublemakers. Her intelligence shines above her peers. While her classmates are gradually starting to read simple chapter books by authors like Beverly Cleary, she's already plowing through the Twilight trilogy.

But for all her intelligence, Doreen is as likely as anyone else to disrupt the class: She's quick to get bored, and she's not especially modest about being the best. When the teacher calls out "those of you who think you're all that," her tablemate—we'll call her "Gwen"—rolls her eyes and looks at Doreen.

"She's talking about you," says Gwen.

Doreen sighs. "I think I'm all that, because I am."

"Well, why do you have to brag about it?"

"Because I am the best."

"Yeah, but if I got a 100 on a math test and you got a 90, I wouldn't act like all that and make you feel bad."

"But I got the 100, and you got the 90," Doreen sighs. "She never gets a 100," she says in an aside about Gwen.

"So? It doesn't mean you have to brag about it!"

"But I do have to brag. I have a big ego."

"Be quiet, ladies!," the teacher yells, the lesson interrupted yet again.

The teacher desperately wants the Doreens of the class to do well: She is noticeably tougher on the bright kids who she knows have the intelligence but lack the discipline they'll need in the higher grades.

As a Latina in the New York City school system, Doreen's odds of finishing high school are about 50 percent. The chances that Doreen will get into a top public high school are low. Latino students make up almost 40 percent of the school system, but at premier city high schools, they are pretty rare: 8.2 percent at Brooklyn Tech, 7.7 percent at Bronx Science, 2.8 percent at Stuyvesant.

Most of the Latino children who will go to these top schools are already enrolled in talented and gifted schools—not schools like Straus. The odds are greater that a bright girl like Doreen will drop out of high school than make it to college.

Meanwhile, the odds are very different at Lower Lab. At the very least, Lower Lab kids will usually go to the NYC Lab School for Collaborative Studies. Many, whose parents paid hundreds or thousands of dollars in tutoring fees for their kindergarten entrance exam, will benefit from similar training to get them into even more prestigious high schools.

It's hard to get to know Lower Lab too well: Administrators don't make it very easy even for parents of prospective pupils to observe the school. The process of getting one of the coveted 56 seats begins in October each year, a full 11 months before the first day of class.

Even a tour can't be had until you've aced the kindergarten entrance exam. According to Lower Lab's website, only 200 tours are given a year, and "qualifying families will be asked to present a qualifying letter during the tour. We kindly request that families who did not qualify for our Kindergarten or First Grade T[alented] and G[ifted] program refrain from requesting a tour as space is limited." The site refers to pre-K and kindergarten classes that don't require testing as "Non-Talented and Gifted Programs."

And in case you get any ideas that Mom and Dad might want to decide together on whether or not Lower Lab is the right fit, forget it: "Tours will be available to only one parent or guardian per qualifying family."

(School officials were just as uncooperative with Voice requests for visits, interviews, or even e-mailed responses to questions.)

From a distance, at least, it appears as if, despite being under the same roof as Straus, the children of Lower Lab are living in a completely different world. It's not just that they show up in fancy cars and wear better clothes. Nor is it even that the equipment seems newer in their classrooms, and that the science lab makes Straus's look barren by comparison. (It does.)

But, as one teacher put it, you can see the message taking hold that the children are already receiving about their station in life: "These children are babies—they're four years old—when we start separating them! When you tell them from such a young age, 'You are more than, and you are less than,'—when you tell them 'You are gifted,' and 'You are not,' they get the message."

To hear the staff of Straus tell it, the teachers of Lower Lab—who have exclusive use of the front door—have gotten the message that they're special, too.

"Some of those teachers, they think that because their children are 'gifted,' that makes them better teachers," says one teacher at Straus. "But why? They've already selected out the highest-achieving kids. They're easy to teach. We have to take anyone who walks in. We have to bring kids to the table."

Teachers at Lower Lab also deal with children sitting in groups, who are no doubt just as tempted to slip into conversations. But the teachers in Lower Lab have a major advantage: They have an adult-to-student ratio half that of Straus's.

It's very noticeable when there's an aide or reading specialist present in a Straus class: The teacher has a much easier time keeping kids quiet than when he or she is on their own.

Being alone is never a problem for teachers in Lower Lab. Each has a full-time teaching assistant in the room. That's twice as much help with students who tend to bring fewer problems to the classroom to begin with. Lower Lab teachers don't have to deal so much with children who live in poverty (9 percent of Lower Lab children receive free or reduced lunch, compared to 73 percent of Straus). The rate of special education is lower (13 percent of Lower Lab to 19 percent of Straus). Even the English language isn't an issue for Lower Lab: Straus has 45 English language learners. Lower Lab? Zero.

And yet all Lower Lab classrooms are staffed with a full-time assistant teacher, paid for by a robust and powerful PTA.

The differences between the PTAs of Straus and Lower Lab may be the most stark of all.

The Straus PTA is described as "almost nonexistent," "not much to talk about," and "well-meaning, but not very powerful" by several people. One parent (incorrectly) thought Straus didn't even have a PTA.

The idea of a fundraiser for the Straus PTA is a bake sale (selling Baked Lays and other "healthy" snacks, that is). Meanwhile, Lower Lab's idea of a fundraiser is an auction. In the 2006–2007 school year, the annual auction brought in $166,289. That same year (the last for which public records are available), the Lower Lab PTA took in more than a quarter of a million dollars, and reported $424,868 in total assets.

The organization also encourages each family to donate at least $950 a year to their child's public education via a direct appeal.

It's African-American History Month, and the Straus fifth-graders are marching up "Understanding Street" to the combination library and computer lab.

Both schools maintain their own labs. Straus's isn't bad at all, and seems well-supplied with flat-screen Macs—it's questionable how much the children retain, though, as each class gets only an hour a week of computer time.

Students find a list of famous black Americans on each Mac. The teacher tells them to pick one to write an essay about, with a few caveats: "No athletes, and no entertainers."

"I know!" one child exclaims. "I'm going to do Martin Luther King!"

"And no Martin Luther King," the teacher says.

"Awww," goes the chorus. "But I already know about him!"

"Exactly," she says. "Time to learn about someone new."

"What about Jay-Z?"

"Is he an entertainer?" the teacher asks so sternly that the normally talkative child doesn't respond.

"Mohammed Ali?" another child asks.

"What did he do?" the exasperated teacher asks.

"He was a—boxer, it says."

"Is that a sport?"

"Oh, yeah."

The teacher moves around the room, trying to help the students pick a subject and begin their research. One child is told he can't write about President Obama, because they've already learned too much about him, too. A lazy boy picks bell hooks. He's surprised to discover that she's a woman, let alone a feminist scholar: "I don't care. Her name starts with 'B,' and I don't want to scroll down anymore," he says, looking at the alphabetized list. "The teacher said we can't do anyone cool. This sucks."

Doreen, hearing about the prohibition on athletes or entertainers, types "boring African-Americans" into Google to find a subject.

The rebellious kids are not the ones that most worry the teacher and the librarian. It's the 10-year-olds who seem to know absolutely nothing about a computer, and are more than halfway through their fifth-grade year. One student can't find the period on her keyboard; another child doesn't know how to use a Web browser.

"How many of you have a computer at home?" the librarian asks. About a third don't raise their hands.

Getting their hands on keyboards for only an hour a week makes it hard for the teacher to make the students master and retain their "prior knowledge," a phrase the teachers in Straus repeatedly use. Teachers seem confident about teaching their kids—getting them to retain and build upon it is another story.

Doreen's search for "boring African-Americans" hasn't yielded too many results. She has gotten it into her mind that she wants to research "that doctor who separated the conjoined twins." She thinks he's male, so she puts "African-American male" into Google, which generates banner ads that the 10-year-old girl probably shouldn't be looking at. (She finally discovers she's seeking Dr. Ben Carson.)

The part-time aide that sometimes helps out is with another class right now. Working in tandem, it's hard for the teacher and the librarian—by themselves—to attend to all of these kids, help each one individually, and prevent them from ending up on the wrong websites. They barely have time to help the children navigate the computers, let alone deal with the content of what they are actually supposed to be researching and writing.

Even the ones with computers at home, the staff knows, are more apt to play games on them than practice their word processing skills. And, come next week, they'll be starting from scratch again with some of the kids, as if this week's computer lesson never happened.

It's 6:30 p.m. in the school cafeteria, and the Lower Lab PTA is about to come to order. Except for one parent, everyone is white. Before the meeting begins, member Patrick Sullivan regales the people assembled with tales of his evening the night before.

Sullivan is Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer's appointee to the Panel for Education Policy. The PEP, made up of five members appointed by the Borough Presidents and eight by Mayor Bloomberg, is the governing body of the Department of Education. Sullivan casts one of just 13 votes that control the entire school system of 1.1 million children.

The night before, the PEP had voted to close 19 struggling high schools. Each will be replaced with multiple schools, creating shared campuses like the one Straus and Lower Lab occupy. The vote came after a marathon nine-hour hearing, marked by racial tension.

Sullivan came off as the folk hero of the night. He stood up for the NAACP when testimony was cut off, to great applause from the crowd. He was one of the five dissenting votes against shutting down the schools.

In an interview with the Voice, Sullivan says that he was sympathetic to many of the protests that the mostly black and Latino parents were waging at the PEP about unequal treatment. But when asked about the inequities between the two schools in the building where his own children are students—where he is on the PTA—he didn't seem to view inequality the same way.

Does he think, for example, that there is a negative effect from having two racially segregated schools under the same roof?

"No, I don't think it has an effect," he says.

"[Lower Lab] is a gifted and talented program, and [Straus] isn't," he adds, more at ease talking about the issue in terms of economics than race. "The gifted and talented criteria is a standardized test that, I believe—and I believe many other people believe—unfairly draws from higher-income children and families, because they are better able to prepare for that test."

Sullivan says that he opposes the standardization of test scores for children citywide: "It used to be that the [talented and gifted schools] had different entrance criteria in different parts of the city, which would reflect the economics of the various zones." When the PEP voted to standardize scores, "I opposed it, and I was the only one who voted against it."

In Lower Lab's case, the sifting done by tests has resulted in a black population of just 3.1 percent.

If Sullivan was uncomfortable talking specifically about the racial differences between the two schools sharing a building, many black parents were not—even though they preferred to do it anonymously.

"We know they get better stuff and more money in Lower Lab," said one Straus African-American mother who works as a teaching assistant in a nearby school, "but there's nothing we can do about it." Another black parent, whose child was zoned for Straus, sent her to another school "so she wouldn't be humiliated by having [Lower Lab] in her face."

"Isn't that something?" the parent said. "I can't believe they put up with walking in through the back door."

Reconciling the disparity between what the schools receive is especially hard for the mother of one of the few African-American students who recently graduated from Lower Lab. "For my son and his development, I would have liked to have seen more students who looked like him."

When asked if she felt uncomfortable knowing her son received superior resources to most of the black students in the building, her gratitude outweighed her discomfort: "If I was on the outside, I'd say that that's not fair. But getting to be in the school, with my son there, I was happy to be the beneficiary of those benefits."

She candidly revealed that Lower Lab was a very good bargain for their money: "When you have 28 kids in a class, and you can give $500 or $950 a year, and you can have another teacher in the classroom and cut the ratio in half—I was happy to do it."

One thing that did seem to unsettle her, though, is her feeling that it happened through strong-arming. "The PTA was able to hire more personnel [teaching assistants]. That's circumventing Board of Ed rules. And in the Board of Ed, they are aware of this. But because the people on our PTA are powerful people, they are able to go out there and get these funds, and got what they wanted."

Another black parent put it more bluntly: "They've set up a private school within a public building, where they can raise money for their own kids, and their kids only."

It's the 99th school day of the year, and there is much to celebrate in the fifth-grade class of Isador and Ida Straus.

Not only is it the Friday before winter recess, but the class is having a lunchtime party (technically, a "cultural celebration"). The teacher has set up an elaborate chafing-dish buffet. Together with some of the children's parents, she has prepared a smorgasbord of foods to celebrate a smorgasbord of causes, including birthdays, Valentine's Day, the Chinese New Year, African-American History Month, and the final day of school.

Once the food is set and warming up, she returns to the carpet, where the children have been reading aloud When Marian Sang, a book about Marian Anderson.

"You see, children?" says the teacher, after Anderson has defeated Jim Crow to become an opera singer. "Marian experienced hardships, but she got over them. Every group has gone through hardships, and has gotten over them—black people, Latinos, Jews, Asians."

"Even white people?" one child asks his neighbor.

The food is served, and a table full of boys begins digging in. "This food is off the shizzle!" proclaims a bespectacled African-American boy. He and one of his best friends, a South Asian kid with a winning smile, are actually free to talk without being shushed for a change. They're arguing over who is taller, and whether or not hair should count in height. (The boy with the trim Afro thinks it shouldn't; the boy with the voluminous poof thinks it should.)

At the next table, a group of girls tries to trick adults in the room into revealing their ages by asking them what Chinese sign they were born under, then looking it up on the zodiac.

It's a festive mood, even though all the adults in the building cannot wait for 2:20 to arrive and their vacation to begin. With a snow day earlier in the week, the children have been unable to go out on the playground ever since, and they're wound especially tightly.

Despite the teacher's ebullience about the coming vacation—she is literally dancing at the thought—the hard work and money it has taken to put on this party shows how much she loves these children. She paid for the chafing dishes, and the food she has prepared out of her own pocket. Like all New York City teachers, she works with a budget of $150 a year—about 83 cents a day—to provide for all the supplies she'll need.

Unlike her colleagues at the other school in the building, there will be no reimbursement from the PTA. No auction is going to provide her with extra books, or a music teacher, or an assistant. Anything extra—like the food she cooked, after teaching all day and commuting four hours—is on her dime.

Once all of the children have been fed, there is still plenty of food. The teacher invites lots of other people to come in. Staff members and other teachers come on by. It seems like everyone is passing through.

Everyone, that is, except people from the other school in the same building.

The schools' PTAs exist on different orders of magnitude: Their teachers don't seem to interact at all. But what about the kids of the two schools? How do they interact with each other? Though they enter through separate doors, do they play on the playground? Can the "talented" and "non-talented" get along during recess?

The truth is, it never comes up, because they never, ever play together.

From arriving at different times, to having separate lunch times in the cafeteria, to having different recesses in the yard, the two schools just don't interact. They co-exist, as one parent put it, "like oil and water."

Dr. Pedro Noguera, a professor of education at NYU's Steinhardt school, and the author of The Trouble With Black Boys: And Other Reflections on Race, Equity and the Future of Public Education, thinks it's problematic to be segregating kids from such a young age: "When you send young kids to school where the racial lines are so stark, there is the process of saying there is something fundamentally different about us, which is why we can't be together.

"Some towns, because they are homogenous, their inability to create integrated schools is limited, simply by the fact that there is nobody else there," he says. "That's not the case in New York City. What we have here is really Plessy at work: separate, without even being equal—but very much separate."

In other parts of the country, cities and counties and states struggle with the inequalities that arise between schools that benefit or suffer from their geography—public schools in wealthy areas generally provide a better educational experience than public schools in poor areas. School districts have always wrestled with ways to minimize these differences, like how money is spent, how children are routed, and how teachers are allocated.

In New York, these striking differences have nothing to do with geography—not when two public schools can offer such unequal environments within the same building. And yet, the mayor's plan, embodied in the rush to close schools and replace them with even more multiple institutions, only seems to be exacerbating these differences.

Concerned about the lack of access for talented programs in Straus, the Department of Education is addressing the situation. Patrick Sullivan says the DOE will be starting a gifted program within Straus this fall, beginning with a kindergarten class.

Now, the zoned children will have the option of getting into a talented program, instead of competing with children districtwide. A girl like Doreen might have the chance to be in a gifted class, without competing against rich families who can pay for tutors. Teachers might not have to work as hard to accommodate their slowest and fastest students in the same class.

But the decision is not being universally heralded.

"Why on earth would [Straus] need to have a gifted class, if there's a gifted school already in the building?" asked one mother. "They say they're doing it to make the school more 'attractive,' but are they doing it just to keep [Lower Lab] segregated?"

"Teza" Trailer

For Filmmaker, Ethiopia’s Struggle Is His Own

Mypheduh FilmsHaile Gerima's new film, “Teza,” stars the Ethiopian-American actor Aaron Arefe as a man from a small village who goes from idealistic student to political exile.

WASHINGTON — Among the courses Haile Gerima teaches at Howard University is one called “Film and Social Change.” But for Mr. Gerima, an Ethiopian director and screenwriter who has lived here since the 1970s in what he calls self-exile, that subject is not just an academic concern: it is also what motivates him to make films with African and African-American themes.

“Teza,” which opens Friday at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas in Manhattan and means “Morning Dew” in the director’s native Amharic, may be Mr. Gerima’s most autobiographical movie yet. It traces the anguished course of an idealistic young intellectual named Anberber from his origins in a small village through his years as a medical student in Europe; his return to Ethiopia, where he ends up a casualty of the Marxist military revolution that overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974; and his exile to West Germany, where he becomes a victim of racism.

“I am from a generation that genuinely wanted a better society and to do something for poor and oppressed people, but which got blinded and lost and turned against its own humanity to become the opposite of what we wanted to be,” Mr. Gerima, 64, said in an interview at Sankofa, a Pan-African bookstore, cultural center and cafe that is across from the Howard campus and also houses his film company’s production offices. “For me, this film is really about displacement, which is a theme that really resonates within me.”

Sometimes that sense of dislocation is literal in his movies, and sometimes it is metaphorical. In “Sankofa” (1993) a black American fashion model on a shoot in Africa is transported back to the 18th century and slavery on a West Indian plantation, while in “Ashes and Embers” (1982) Mr. Gerima explored the disillusionment of African-American veterans returning from the Vietnam War to urban poverty and hopelessness.

Mr. Gerima first arrived in the United States in 1967 to study theater at the Goodman School of Drama in Chicago; his Peace Corps teachers in Ethiopia, impressed by his talent, had arranged for his admission there. But he was not prepared for the politics of race in America, and initially felt estranged not just from the whites whose lawns and gardens he tended to support himself, but also from African-Americans.

“I had never been challenged the way African-Americans are in America, and encountering racism shocked me to the point that I had nosebleeds,” he said. “But I didn’t want to be black American, I didn’t want to identify with their situation — I felt they were slaves and I was not. I didn’t believe they came from Africa; I felt they were a different species sprouted from the plantation. The intellectual distance was too great.”

Unhappy with the acting roles he was offered — all the blacks “were just park benches and lamp posts” — Mr. Gerima transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles, where he quickly won an acting award and developed ties to the Pan-African black-power movement. He switched to film after the shock of being exposed to Latin American directors like Glauber Rocha, Fernando Solanas and Miguel Littín made him realize, he said, that his story was “equally as important and valid” as those he was accustomed to seeing in Hollywood productions.

The filmmaker Charles Burnett, a classmate who went on to direct “Killer of Sheep” and “To Sleep With Anger” and remains a friend, recalls: “Even then he knew what he wanted to do and was very outspoken and engaged, with strong opinions and a deep identification with people of color and their struggle. He has his own code, he’s very energetic and kinetic, and you can feel his films the same way.”

Mr. Gerima first drew attention in the mid-1970s with “Harvest: 3000 Years,” about an Ethiopian peasant family struggling to survive under feudalism; it was filmed as Haile Selassie’s imperial rule was collapsing. “In a way,” Mr. Burnett said, “you can see the roots of ‘Teza’ there, the focus on village life and the concern with Ethiopian history.”

But that film also led to the start of Mr. Gerima’s troubles with the Derg, the Communist military junta that replaced Haile Selassie. The new regime declared his film “the property of the Ethiopian people” and would only allow him to make another movie in his homeland if he agreed to accept what they called their “jurisdiction” over his work.

“When they said that, I couldn’t wait to take the plane out, because I knew my freedom was gone,” Mr. Gerima said. “I would have died. I don’t fit well in dogma of any kind, even the dogma I create myself, because the next day I get up betraying it.”

Mr. Gerima describes “Teza,” which includes an evocative jazz-based soundtrack by Vijay Iyer and Jorga Mesfin, as an impassioned but “imperfect” film. Because financing was difficult to obtain, it took him more than a decade to complete, and the scenes shot in rural Ethiopia, many of them with illiterate peasants in the cast, with a mainly Western crew, posed one logistical challenge after another.

“Even to bring equipment to the locations was difficult and unforgettable,” said Mr. Gerima’s sister Salome, who helps produce his films. “The electricity came from the village generator, which sometimes would be turned off as we were filming, and so we had to negotiate. More than money, patience was required.”

Aaron Arefe, a 29-year-old Ethiopian-American who plays Anberber, described the shoot as “a rite of passage and a life-changing experience.” Born in Los Angeles, Mr. Arefe moved to Addis Ababa as a child and returned to California for college. But nothing prepared him for scenes shot in an area of caves in northwest Ethiopia.

“The people in the surrounding community came to watch us and asked what we were doing,” Mr. Arefe recalled. “When we said, ‘Making a movie,’ they asked, ‘What is a movie?’ When we said, ‘Like the stories you see on television,’ they asked, ‘What is television?’ Only when we said, ‘The visual version of what you hear on a radio,’ were some of them able to understand.”

Over the last year or so, “Teza” has been plying the festival circuit in Europe and Africa, winning awards in places like Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Venice; Carthage, Tunisia; and Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

Françoise Pfaff, a Howard University colleague and the author of the book “Twenty-Five Black African Filmmakers” (1988), noted that Mr. Gerima was the first Ethiopian director to win the top prize at the Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou, a considerable achievement, she explained, given that “Teza” was filmed in neither English nor French, the two dominant languages in African cinema.

“He’s very much respected both for his militancy, the honesty of his political involvement, and his talent and body of work,” she said of Mr. Gerima. “In ‘Teza,’ he really was able to capture light and shade, the full majesty of the African landscape, which gives the film a tremendous strength and beauty.”

“It’s no longer starving Ethiopia,” she added. “It’s a story of displacement and loss that resonates universally, and that also is a relief.”

==========================

Haile Gerima- Using film to voice the story-teza

===========================

One On One With Haile Gerima

Back in May, after just finding out that his latest film, Teza, had just won The Golden Stallion of Yennenga at FESPACO, (Festival panafricain du cinéma et de la télévision de Ouagadougou, I wrote here about Haile Gerima, the uncompromising Ethiopian director and story teller, a member of the 1960s UCLA movement, The Los Angeles School of Black Film Makers, a collective that also included contemporaries the likes of Charles Burnett (To Sleep with Anger, Killer of Sheep) and whose second wave included Julie Dash (Daughters of the Dust). Gerima, a self described third world independent filmmaker, is a professor of film at Howard University.

The following videos, from Al Jazeera English’s Riz Khan’s One on One, which takes an intimate look into the lives and philosophies of newsmakers and celebrities, were aired in February of this year and spotlight Gerima’ inspirations, influences, and steadfast independent views on film.

Following Tambay’s recent podcast earlier this week, featuring two contemporary independent African-American filmmakers, Dennis Dorch (A Good Day To Be Black And Sexy) and Barry Jenkins (Medicine For Melancholy), whose films were successfully picked up by distributors at Sundance last year and went on to get limited theatrical release, but who still await that meeting or telephone call that will bring the jackpot Hollywood big bucks, the career of someone like Gerima is one worth contemplating for its persistence, tenacity, and uncompromising integrity.

Gerima says he makes his films, essentially, for himself, but adds:

“If I’m hungered of some subject matter, I find a common, collective population that equally is hungered for the story I tell.”

This hungered population he speaks of would include not just Africans but also African-Americans, populations whose stories, he feels, and many here might agree, the Hollywood machinery holds hostage to paternalism, thereby compromising the objective of breaking down barriers through filmmaking. Seeing as, like me, Gerima believes that storytelling is the key to filmmaking, the implication, obviously, is that, with the key all too often taken away from filmmakers (and writers) of colour, the doors to creative expression and the opportunity to contribute to a shared human experience through film remain somewhat closed to people of colour.

As someone who comes from a family of storytellers and lived what he calls an “amplified life” in Ethiopia, he describes his arrival in the US in 1968, aged 21, like suddenly having his humanity negated, and says that his own racial confrontations, though nothing in comparison to the African-American experience, were enough to actually make him doubt his quality as human being. The making of his best known film, Sankofa (1993), which took nine years to make, and which, because it engaged the subject of slavery and racism, some thought would torpedo his opportunity to be a good filmmaker, was something he felt he had to do to overcome his own struggle, as an Ethiopian knowing nothing of slavery and African-American history prior to arriving in America, with understanding African-Americans.

Having thought everything would be a piece of cake after finally finishing Sankofa, it took almost 14 years to finish Teza, about the displacement of African intellectuals, and proved even more problematic to raise money to make than Sankofa.

His advice to his young filmmakers is simple:

“Not to look at cinema as a telegram to send to somebody, whether it’s moral or entertainment.

…Find who you are – your voice will be unique, but if you imitate already existing voices, you pre-empt yourself.

…Find your voice as you tell the story.”

Gerima, now in his 60s, still writing scripts continuously and says he would like to be remembered as a symbol of resistance in a society that wants to destroy individual quality, even though he feels he’d be an imperfect example.

One on One: Haile Gerima - Part I

AlJazeeraEnglish — February 07, 2009 — This week on One on One meet the Ethiopian director, story-teller and philosopher.

One on One: Haile Gerima - Part II

================================

Gerima/Teza – Golden Stallion of African Film

About a month ago, a friend asked if I’d heard of Haile Gerima or seen any of his films, in particular, Teza, his latest. I had, indeed, heard of Haile Gerima and had also seen one of his films, many moons ago (early 90s) called Sankofa, an evocative, ethereal tale that looks at slavery through the eyes of a 20th century African-American model who visits Ghana and sees into the past. I told my friend I’d keep my eyes peeled for any screenings of Teza, saying I wouldn’t hold my breath as I expect any such events to be few and far between…

But what I didn’t know at the time is that Teza had just won The Golden Stallion of Yennenga at FESPACO, (Festival panafricain du cinéma et de la télévision de Ouagadougou, or The Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougo for tho of us who don’t parlez le francais). FESPACO is the largest and most globally renowned African film festival, was created in 1969 in Burkino Faso, and The Golden Stallion is its top prize. Gerima’s Teza has screened at film festivals world-wide and won a slew of other accolades including the Golden OSELLA for Best Screenplay and Special Jury Prizeat the 65th Venice Film Festival, and the Dioraphte, at Rotterdam Film Festival.

I’m hoping that this will make the film that little bit more available. Of course, I’m not expecting multiplexes or anything so accessible, but at least the odd screening here and there would be nice and, with the film’s global success, should be more likely.

Teza was 14 years in the making and is set in Ethiopia during the marxist regime of Haile Mariam Mengistu, who was in power in Ethiopia from 1974 until 1991. It tells the story of Anberber, a young medical doctor who returns home to his country after training in Germany, to find it completely devastated by the authoritarian regime.

However, despite its political context, in an interview with the Daily Motion website, Gerima concedes that the film is not focused on politics issues. Gerima say the film is “more about a generation. It’s a group of African intellectuals at this historical moment, being very exiled from home or abroad. So it’s a displacement of African intellectuals”.

Himself a native of Ethiopia, Haile Gerima migrated to the US in 1968 and studied film at UCLA in the 70s, where he became a member of the Los Angeles School of Black Film Makers, a collective that also included the likes of Charles Burnett (To Sleep with Anger, Killer of Sheep) and Julie Dash (Daughters of the Dust). Gerima is a professor of film at Howard University, Washington DC.

5th Annual Warren Adler Short Story Contest

Posted on 11 January 2010 by Warren Adler

The 5th Annual Warren Adler Short Story Contest will run from January 11, 2010 to April 11, 2010. The rules are simple. The stories must be no longer than 2500 words. A $15 entry fee is charged to cover the prizes and various expenses associated with the contest.

Subject matter is completely open to the author. Judges will be announced shortly. The goal of the contest is to encourage and publicize the short story as a viable and quality literary form. In the past few decades the short story has lost the popularity it once enjoyed when magazines were plentiful and the short story was a feature of many of them. Indeed, many authors earned their living by writing short stories exclusively.

We are quite proud of the winners we have chosen in previous contests. Moreover the entries have been terrific and the quality of the writing quite wonderful, making it extremely difficult for the judges to make their ultimate choices. We are happy to report that our contest has gained a prestigious reputation for careful judgment and absolute fairness.

We highly recommend aspirants to read the winning stories chosen by our judges in previous contests.

We look forward to your entries.

When your story is ready, click Pay Now below to make payment (using Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover or PayPal) and proceed to Contest Entry Form.

Cash prizes will be offered to the winners as follows:

- First Prize: $1000

- People’s Choice Prize: $500

- Three remaining finalists: $150 each

As in previous contests all winners will be posted on the Warren Adler website.

We are exploring the possibilities of publishing an e-book anthology under the banner of Stonehouse Press of all contest winners, depending on permissions of the authors. If this can be done, we will make the announcement when the winners of this contest are chosen.

The Wallace Stegner Prize in Environmental and American Western History

$10,000 Book Publication Prize, Presented by the University of Utah Press

The Wallace Stegner Prize will be awarded to the best monograph submitted to the Press in the subject areas of environmental and American western history. To compete for this award, manuscripts must emphasize research in primary and secondary sources and quality writing in the tradition of Wallace Stegner. The winning manuscript will demonstrate a commitment to scholarly narrative history that also appeals to more general readers. These criteria reflect the legacy of Wallace Stegner as a student of the American West, as a spokesman for the environment, and as a teacher of creative writing. The winner of the Wallace Stegner Prize will receive a $10,000 award and a publication contract with the University of Utah Press.

2010 Prize Submission Guidelines

- Manuscripts must be in English and in double-spaced Courier 12-point font. They should be otherwise formatted to conform to the manuscript and graphics guidelines stipulated on the Press Web page under "Submission Guidelines."

- Manuscripts must be postmarked between January 1 and December 31, 2010.

- Manuscripts that do not win the Wallace Stegner Prize will also be considered for book publication.

- Manuscripts will not be returned and will be recycled after the competition.

- Simultaneous submissions are not permitted.

- Portions of submitted manuscripts may have appeared previously in journals or anthologies, but previously published monographs will not be considered.

- The competition is open to all authors except current students, faculty, and staff of the University of Utah.

- All submissions should include a cover letter, C.V., and complete manuscript, including all illustrations and supplementary materials.

A panel of historians and representatives of the Press will determine the winning submission. Awardees will be contacted directly and the results of the competition will be posted on the Press Web site by June 1, 2011. Please do not call the Press or the judges to check on the status of your submission. The decision of the judges is final.

The winning manuscript will be announced in the Fall/Winter 2011 Catalog.

Please send all submissions to:

The University of Utah Press

J. Willard Marriott Library

Suite 5400

University of Utah

295 South 1500 East

Salt Lake City, Utah 84112-0860

Agha Shahid Ali Poetry Prize

"The world is full of paper. Write to me."

- Agha Shahid Ali, "Stationery"

Honoring the memory of a celebrated poet and a beloved teacher, the Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry is awarded annually and is sponsored by the University of Utah Press and the University of Utah Department of English.

$1000 Cash Prize and Publication; Reading in the University of Utah's Guest Writers Series.

2010 Prize Submission Guidelines

- Manuscripts should be between 48 and 64 typed pages. Attach a cover sheet providing complete contact information, including name, address, telephone, and email address. No other identifying information should be included on the title page or on the manuscript itself.

- Submissions must be in English.

- Manuscripts must be postmarked during February 1 through April 15, 2010

- A check for the nonrefundable reading fee of $25 payable to the University of Utah Press must be included with the submission.

- Manuscripts will not be returned and will be discarded after the competition.

- Submitted poems may have appeared previously in journals, anthologies, or chapbooks.

- The competition is open to poets who have previously published book-length poetry collections, as well as unpublished poets.

- Simultaneous submissions are permitted; however, entrants must notify the Press immediately if the collection submitted is accepted for publication elsewhere during the competition.

The winning manuscript will be chosen by a finalist judge. The series editor will contact the winning poet and the results of the competition will be announced on this website in September of 2010. Please do not call the Press or the department of English to check on the status of your submission.

The winning collection will be published by the University of Utah Press in the spring of 2011. The winner will receive a $1,000 cash prize and will give a reading in the University of Utah's Guest Writers Series reading to take place during the fall or spring following publication. Travel and accommodations paid by the University of Utah English Department.

Address submissions to:

The University of Utah Press

c/o The Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry

J. Willard Marriott Library

Suite 5400

University of Utah

295 South 1500 East

Salt Lake City, Utah 84112-0860