Marcus Garvey

Clear Marcus Garvey's Name

By Geoffrey Philp

To be delivered to: President Barack Obama

“We are petitioning President Barack Obama to issue a full pardon and to clear the name of Marcus Mosiah Garvey, a national hero of Jamaica.”Marcus Garvey, founder of the UNIA, was arrested by the FBI under the Hoover administration and charged with mail fraud for which he was sentenced to five years in prison. Although his sentence was eventually commuted by President Calvin Coolidge, it is now abundantly clear that Garvey did not commit any criminal acts, but as Professor Judith Stein has stated, “his politics were on trial.

Previous petition signers:

Loading...

Signer Date Place 59. Jawara Adisa-Farrar May 29, 2011 Northridge, CA 58. Stephen Bess May 29, 2011 Montgomry Vlg, MD 57. Khadijia Bulli May 29, 2011 st catherine 56. Kester Mtambanengwe May 29, 2011 Sheffield 55. Dean Grant May 29, 2011 Surrey 54. Ariel Bowen May 29, 2011 Kingston 5 Let's use Facebook to make this work! 53. Janice M Budd May 29, 2011 52. Karlene Gordon May 29, 2011 brooklyn, NY 51. Anneke Rousseau May 29, 2011 London Long overdue! 50. Peter Nevins May 29, 2011 North Miami, FL Next > >

LADY ELIX PRESENTS

SIGN OF THE OX:

GIL SCOTT-HERON'S

IN LOVING TRIBUTE

(APRIL 1, 1949 - MAY 27, 2011)

According to Chinese Astrology, folks who are born under the Year of the OX are supremely self-assured, and as a result are noted for inspiring confidence in others. Generally patient and thoughtful, they measure their words, and will speak clearly and concisely often when it matters the most.

Gil Scott-Heron’s music reflects the above statement in many ways to those who listen, dance & raise their consciousness to his expressions. I can go on about his contribution as one of our most prolific singer, songwriter, musician, social-commentator, author & poet.

The words and the messages in his music are clear and precisely to the point. We should care about humanity and the world-at-large but somehow that message got lost. So I’m here to let you know that his music is the constant reminder of what we need to do in the here and now. I recall the lyrics from ‘Work for Peace’ when Gil said, ‘We can’t do everything but we can do something’. I feel as a human race we ought to get it going but somehow we remain stuck in the mud. As I’ve been on this planet for many years and the message is still not getting through to many people and it’s sad. The lives of Malcolm, & Martin were taken but their messages should’ve stayed with us.

I recently caught a glance of a YouTube video of Gil at a music festival press conference discussing a book he’s working on ‘The Last Holiday’. The book should be released -GODWILLING- sometime this year. It’s Gil’s diary on his life as well as his involvement with Stevie Wonder’s crusade to make MLK’s birthday a National Holiday. A must read with great interest!

Happy Birthday Gil and Peace Be with You always, brother!

As-Salaam-Alaikum,Lady E

LISTEN HERE:

DOWNLOAD HERE:

http://www.divshare.com/download/14463225-4ba

AND AS A BONUS...check out Gil Scott-Heron's 2010 interview during Hungary's Mediawave Festival.

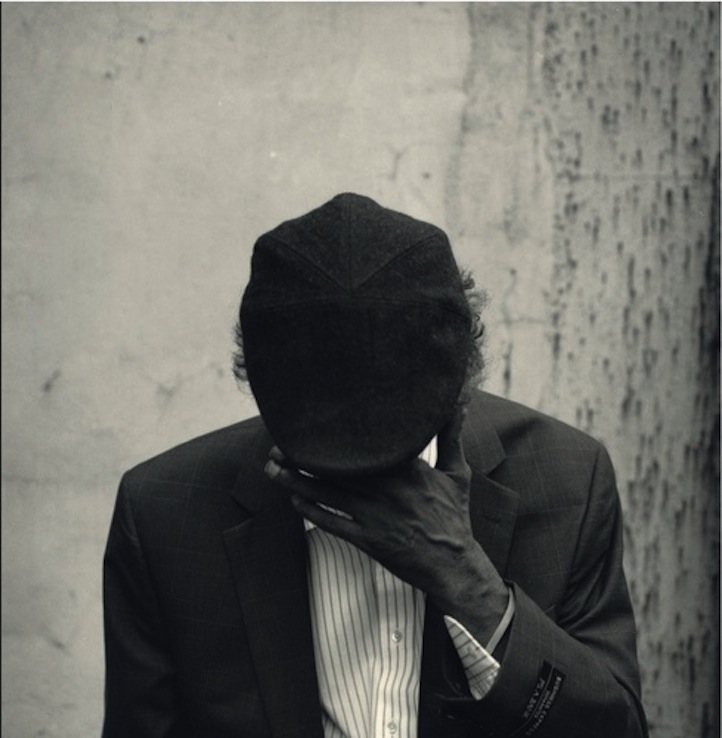

Gil Scott-Heron

__________________________

Abiodun Ayewole and Jessica Care Moore on a ferry crossing the Mississippi River in New Orleans.

Remembering Gil,

with Love,

One of your daughters

by Jessica Care Moore on Saturday, May 28, 2011 at 11:54am

I'd just hung up the phone with a revolutionary sister/abolitionist in the fight against the death penalty, when my friend sent me the text that Gil Scott had passed. I literally gasped for air.

I'm just home from New Orleans where i spent a weekend with one of my other fathers in poetry, Abiodun Oyewole and was able to hang and laugh with another one of my elders, Kalamu Ya Salaam. I remember years ago being on a panel in Atlanta with some other poets of my generation, and someone ignorantly suggested that talking about the literary and spoken word greats that came before us, was "name dropping."

That's how lost we've become.

I called Dun, and Umar first. I searched my cell for Sonia's number. I started to wonder how long it'd been since i'd seen Jayne Cortez. I smiled because i've seen Ntozake so many times this year. I thought of Haki and how generous he's been to me and my son. I cry hard, uncontrollably.

I just found an essay about poetry and the new marketing of "spoken word" i wrote in 1999. I was the first poet in residence at University of Mass, Dartmouth. I was only 27. I was so serious, about my work, and the work of our generations poets. In 1999 I was making a good living as a poet, lecturer, and young book publisher. There was no Def Poetry. The poets I was around were connected to a continuum and didn't focus on "blowing up."

I'd won the Apollo and a hand full of us were attempting to make the connection between our poetic ancestors, and the living legends. Only a few of us were making a living as poets, or poet/teachers/performers: Me, Saul (Williams), Paul Beatty, Reg E Gaines, Tony Medina, Carl Hancock Rux, Ras Baraka, Tracie Morris, Ursula Rucker, Willie Perdomo, asha bandele, Suheir Hammad, Kevin Powell..there are more. We understood there was a Black Canon, and we wanted in.

Of course I knew Gil. We all knew him, and he knew us too. I have some great memories of him. I remember The Village Voice doing a photo shoot with us in the late nineties..it was me, Gil and Sarah Jones. We were all wrapped in yellow police tape in front of Wetlands. I need to find the article. Gil was always so loving, and his smile was electric. His voice was black music and we could see the fine, fiery, young revolutionary in the hearts of his eyes.

One of my favorite Gil stories is when a Hip Hop Magazine asked me to debate a poet about whether poetry was hip hop or not. I was on the "YES" side, and was later told i would be debating with Gil. When Gil found out the poet was me, he turned down the article and said he wouldn't debate against me, because i was his sister, and we were on the same side. So, whatever i was saying about poetry and hip hop, he would likely agree.

It was an amazing moment for me. He was so grounded despite his legendary status, and even seconds before he would go on stage, he would just be kicking it with whomever was around. He was daddy cool. A warm, gentle spirit. Our unfiltered blues.

No matter what he seemed to be going through health wise, i never saw him waiver on stage. When he hit the mic or touched the keys, it was magic and it transformed the room.

One of my last shows with Gil Scott was at SOB's. We hit there together, along with Roy Ayers a few times. That's when i'd formed my band, Detroit Read, in NYC, and was busy following in the footsteps of the Word, Sound Power Movement, much like, poets, Sharrif Simmons, (who carries his likeness and sound), Carl Hancock Rux, Mike Ladd, Saul Williams, Dante (Mos Def), Latasha Natasha, Liza Jesse Peterson, and others. Not every poet was comfortable surrounded by afro-electric rock and roll soul-amplification, but some of us, lived for it and still do.

A few years ago i filled in for him at Western Michigan when he didn't show up for a gig. When i spoke to the student organizer and realized his birthday was just the night before..i laughed..and said, "Now you know you weren't supposed to book him after a party day like that!" :)

Gil dying so young, reminds me of how we must take care of ourselves on every level. We cannot lead a revolution if we can't run to the corner. We must heal mental illnesses, eat healthy foods and raise our children fully aware of who they are in relationship to the world.

Gil was loved by the world, and sometimes revered, like many of us, in foreign countries, more than the country we were born into. Our babies must know his music, his books. We cannot continue to allow mediocre mainstream artists who don't educate our minds or challenge the status quo, to be the most celebrated.

There is a beauty in having a cult following. When young people have memorized my poems better than me, when I don't have an major marketing machine beyond my work, it feels even more powerful.

Still, we need Gil and Gil's poetic children, to not be "outsiders," anymore.

We are the forebears of truth, of culture. Too "radical" to be invited, but always the artists with the most

relevant and provocative work. The artists who should be "invited" and "celebrated" are the ones i know who do work in the prisons, fight to teach in the schools, and write and speak truth to power.

Gil found the balance between the page and stage line i have walked for years.

I will continue doing this work, and shouting his name and teaching his work and grace, the rest of my artistic life.

Gil is/was revolutionary music. Gil is/was style and integrity. Gil is/was our teacher.

Gil Scott's voice will forever live.

I will "name drop" him for centuries to come

Gil

lover of his people

Gil

warrior of words

Gil

harlem smile and gansta lean

Gil

pointed his weapon in the right direction

Gil

re-wrote the dictionary

Gil

gave me wings

Gil

knew we almost lost Detroit

Gil

is poetry in a bottle.

Gil

is laughter and harlem sunsets

Gil is soul unleashed

Gil is rebellion

Gil continues

Gil ancestor

talking with langston

hugging lucille

deconstructing american

schizophrenia with Ai

playing cards with Pac

writing more poems

watching us attempt to

outlive our circumstances.

another day.

Love you. Miss you.

It was an honor to share the stage with you. To learn from you.

To know you.

In solidarity and poems,

jessica Care moore

May 28th 2011 12:29pm

__________________________

Gil Scott-Heron performing "Blue Collar" at the Gobi Tent at Coachella on Friday, April 16, 2010.

__________________________

It's Your World

Gil Scott-Heron died last night [May 27, 2011]. Official news outlets report the “cause is unclear” but those of us who grew up listening to his music and poetry, know our prophetic legend was finally run down by the demons that were his addiction. Gil Scott began his recording career with the independent label Flying Dutchman Records (a nod to the Leroi Jones play) in 1970, at the height of the Black Power movement. He was to America’s ghetto what Bob Dylan was to the rest of the country, a militant voice of protest. His influential 1974 album Winter in America produced soul-aching ballads and timeless classics and caught the attention of music impresario Clive Davis who made Scott-Heron, in 1975, the first artist he signed to Arista Records.

Hip-hop did much to strip shame from poverty, but with songs like “Whitey on the Moon”, where he juxtaposed high health care bills, rat-infested apartments and late rent payments with space race budgets, Gil Scott’s songs restored humanity to America’s inner-city poor. His “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” survived generations. He is widely regarded a forefather of hip-hop, with artists (most recently, Kanye West) paying tribute to him for decades. His later live shows were often emotionally skinless; in later years he barely sobered up for concerts, yet the clarity of his sharp commentary cut through his own fog. Known to extend his haunting blues song “Angel Dust” past thirty minutes, he’d grip the neck of a large bottle of cognac onstage and break from his lyrics to make concise, biting political criticism. He was the unshaven everyman who looked like he could barely get past his own venue’s security, but when he sang, his voice remained a strong bellwether. Gil Scott-Heron’s thirteenth and final album I’m New Here was released in February of this year. He didn’t take care of himself, he never conquered his need to self medicate, but he never stopped caring for us.

>via: http://lifeandtimes.com/its-your-world

__________________________

Gil Scott-Heron and his Amnesia Express from March 14, 1990 in London, UK.

__________________________

This week in the magazine, Alec Wilkinson profiles Gil Scott-Heron. (Subscribers can read the full text; others can buy access to the issue via the digital edition.) Here Monique de Latour narrates a slide show of her never-before-seen photographs of Scott-Heron, whom she met in 1995. She talks about their relationship, his musical performances, and his struggles with drug abuse.

>via: http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2010/08/video-gil-scott-heron....

Scott-Heron performing in 1998. Photograph by Monique de Latour.

Gil Scott-Heron is frequently called the “godfather of rap,” which is an epithet he doesn’t really care for. In 1968, when he was nineteen, he wrote a satirical spoken-word piece called “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” It was released on a very small label in 1970 and was probably heard of more than heard, but it had a following. It is the species of classic that sounds as subversive and intelligent now as it did when it was new, even though some of the references—Spiro Agnew, Natalie Wood, Roy Wilkins, Hooterville—have become dated. By the time Scott-Heron was twenty-three, he had published two novels and a book of poems and recorded three albums, each of which prospered modestly, but “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” made him famous.

Scott-Heron calls himself a bluesologist. He is sixty-one, tall and scrawny, and he lives in Harlem, in a ground-floor apartment that he doesn’t often leave. It is long and narrow, and there’s a bedspread covering a sliding glass door to a patio, so no light enters, making the place seem like a monk’s cell or a cave. Once, when I thought he was away, I called to convey a message, and he answered and said, “I’m here. Where else would a caveman be but in his cave?”

Recently, I arrived at his apartment while he was watching fight films with Mimi Little, whom he calls Miss Mimi. Miss Mimi helps run his affairs and those of his company, Brouhaha Music; the living room of his apartment is the company’s office. They were watching Muhammad Ali knock down George Foreman in the eighth round of the Rumble in the Jungle, in Zaire, in 1974. Scott-Heron was wearing baggy gray sweatpants, a red-and-white-striped polo shirt, and white socks, and he stood in front of the television, lifting one foot, then the other, as if the floor were hot. When Foreman collapsed, Scott-Heron pretended to be Ali chastising him as he lay on his back. “That’s the best you can do?” he said. “I had about enough of you.”

“It’s done now,” Little said.

“I thought you could hit,” Scott-Heron said. “You hit like a baby.”

A crowd flooded the ring. “Look at these silly people,” Scott-Heron said. A large black man in a blue blazer wrapped his arms around Ali from behind and lifted him, and Ali waved his arms like a cranky baby. “Brother try to pick up Ali here. He says, ‘Put me down.’ ”

All you could see then of Ali in the blending swarm was his head and shoulders, so he looked like a bust. “Ali’s thirty-two, having been exiled to nowhere,” Scott-Heron said. “Unbelievable odds. I like to see unbelievable odds, because that’s what I’ve been facing all these years. When I feel like giving up, I like to watch this.”

The phone rang, and Little answered. She said it was Kim Jordan, his piano player. Little covered the phone and said, “She wants to know what to practice.” Scott-Heron had a performance that week in Washington, D.C. He kept his eyes on the screen. “ ‘Lady Day and John Coltrane,’ key of A,” he said. “ ‘I Call It Morning,’ ‘Give Her a Call.’ ”

“He’ll give you a call,” Little said.

“No, that’s the name of the song, ‘Give Her a Call,’ ” Scott-Heron said.

Little hung up, and Scott-Heron sat down on the couch, facing the screen. The couch was brown, with so many little black burn circles that they seemed worked into the fabric’s design. A few extension cords crossed a rug on the floor, and lying at his feet among them was a propane torch. Taped to the wall facing him was a piece of paper on which he had written, in capital letters, with a Sharpie, “NOTHING NICE TO TALK ABOUT?NOTHING GOOD TO SAY?NO YUKS?NO SMILES?THEN SHUT UP.THE MNGMT.” On the shelf of a cabinet were some books, and some DVDs, which he buys at a video store next door to the Apollo Theatre, on 125th Street. He especially likes shows and movies and cartoons from his childhood, such as “Top Cat” and “Rocky and Bullwinkle” and “Underdog.” “Your life has to consist of more than ‘Black people should unite,’ ” he said. “You hope they do, but not twenty-four hours a day. If you aren’t having no fun, die, because you’re running a worthless program, far as I’m concerned.”

Little said that she was leaving to run errands. Staples was having a two-to-a-customer sale of something she needed a quantity of. “I’m going back two or three times,” she said. “I have a disguise, and I know where four Staples are.”

When she left, Scott-Heron seemed briefly at a loss, then he said, “We should listen to some music.” He put on a song of his from years ago called “Racetrack in France,” which is about a festival he played in the seventies. “I don’t feel as comfortable playing something of somebody else’s,” he said shyly. “I can’t say how the good parts got put together.”

Sometimes when I spoke to people who used to know Scott-Heron, they told me that they preferred to remember him as he had been. They meant before he had begun avidly smoking crack, which is a withering drug. As a young man, he had a long, narrow, slightly curved face, which seemed framed by hair that bloomed above his forehead like a hedge. The expression in his eyes was baleful, aloof, and slightly suspicious. He was thin then, but now he seems strung together from wires and sinews—he looks like bones wearing clothes. He is bald on top, and his hair, which is like cotton candy, sticks out in several directions. His cheeks are sunken and deeply lined. Dismayed by his appearance, he doesn’t like to look in mirrors. He likes to sit on the floor, with his legs crossed and his propane torch within reach, his cigarettes and something to drink or eat beside him. Nearly his entire diet consists of fruit and juice. Crack makes a user anxious and uncomfortable and, trying to relieve the tension, Scott-Heron would sometimes lean to one side or reach one hand across himself to grab his opposite ankle, then perhaps lean an elbow on one knee, then maybe press the soles of his feet together, so that he looked like a swami.

Scott-Heron’s voice has always been more of a declaimer’s voice than a singer’s voice—when he was young, he sounded like a writer singing. In 1971, he recorded a second version of “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” and the bassist Ron Carter, who played on it, told me, “He wasn’t a great singer, but, with that voice, if he had whispered it would have been dynamic. It was a voice like you would have for Shakespeare.” Smoking cigarettes erodes a singer’s subtlety and range, and Scott-Heron has smoked for decades, making his voice less versatile but raspier and even more idiosyncratic.

Scott-Heron says that he writes songs and records them all the time, but he has made only two albums since 1982. (Between 1970 and 1982, he made thirteen.) He writes at night, when it is quiet, but only, he says, when the spirits bring him a line or a melody.

Recently, though, Scott-Heron has returned to prominence, having released an album called “I’m New Here,” which has brought him a new, younger audience. It is the result of the British hip-hop producer Richard Russell’s sending him a letter in 2005 asking if he wanted to make a record. As a teen-ager in London in the nineteen-eighties, Russell had seen Scott-Heron perform. He also knew his music from clubs that played rare groove, the British term for obscure, older soul, funk, and Latin records, which hip-hop musicians covet for samples.

Scott-Heron and Russell met in 2006, at Rikers Island, where Scott-Heron was being held for a parole violation. Since 2001, he has been convicted twice of cocaine possession. The first time, he was arrested by cops who said that they saw him shake the hand of a man on a street corner and accept a small piece of tinfoil. The second time, cocaine that he had hidden in the lining of his bag showed up on an airport X-ray. A guard read on Russell’s paperwork the name of the prisoner he had come to see and said, “Don’t tell me it’stheGil Scott-Heron.”

“I’m New Here” is a reverent and intimate record, almost more field work than entertainment—a collage partly sung and partly talked, and made largely from fragments of Scott-Heron’s poetry, handled here in a voguish manner. It presents a notional version of Scott-Heron, which is Scott-Heron as hip-hop practitioner.

Scott-Heron recorded the songs and his poems, and Russell added the hip-hop tracks that accompany them. “This is Richard’s CD,” Scott-Heron says. “My only knowledge when I got to the studio was how he seemed to have wanted this for a long time. You’re in a position to have somebody do something that they really want to do, and it was not something that would hurt me or damage me—why not? All the dreams you show up in are not your own.”

“I’m New Here” is twenty-eight minutes long and has fifteen tracks, four of which are songs, one of which Scott-Heron wrote. Russell left the microphone on between takes and during discussions, and so he collected asides and observations, which he presents as interludes.

The record starts and ends with excerpts from a poem written thirty years ago, called “Coming from a Broken Home,” which includes the lines “Womenfolk raised me and I was full grown / before I knew I came from a broken home.” Russell embedded the reading in a sample from a Kanye West song, a hip-hop self-reference, since Kanye West had already sampled Scott-Heron.

The first song, “Me and the Devil,” by Robert Johnson, is an account of a man who hears the Devil knocking early in the morning on his door. In Johnson’s version, delivered in his clear, glottal voice, the character is a violent reprobate. Scott-Heron portrays him as boastful, lunatic, and malignant—proud to be acknowledged by someone capable of appreciating the true cast of his soul. He amended one of the words, though. “I have this philosophy from further back in my family about beating women—that’s what this song is about,” he says. “ ‘Me and the Devil walking side by side, I’m going to beat my woman until I’m satisfied.’ That’s why the Devil’s coming to get him, that’s why he’s going to Hell, because he’s a hitter, he beats his woman. And that’s why he’s expecting him, because he’s resolved. I’m not hooked up that way, so I sing, ‘I’m going to see my woman.’ The song’s like a confession.” (Even so, Scott-Heron pleaded guilty in 1999 to assaulting a woman named Monique de Latour, who said that he threw a drafting table at her and cut her hand.)

The song Scott-Heron wrote, “New York Is Killing Me,” is a blues sung against a spare background of syncopated handclaps and looped fragments. His voice is weary and raw. “The doctors don’t know, but New York is killing me,” he sings. “Bunch of doctors come around, they don’t know, that New York is killing me / I need to go home and take it slow down in Jackson, Tennessee.”

More than one romance threads itself through “I’m New Here”—the most prominent of which is a younger man’s veneration of a charismatic elder. Aside from liking Scott-Heron’s music, Russell regards him as “genuinely philosophical,” he told me. “He’s not hung up on time or ordinary circumstances, and I’ve never come across anyone as interesting to talk to.” Russell has said that a difficulty of working with Scott-Heron was that sometimes he wouldn’t show up. A philosopher might miss appointments, but so might someone with a propane torch in his apartment, even if he is a philosopher.

There is a gentleness in Scott-Heron’s nature that suggests his childhood among the stern, intelligent women he pays homage to in “Coming from a Broken Home.” His father, Gilbert Heron, who died in 2008, and whom he never much knew, was a soccer player who grew up in Jamaica. In Chicago, Gilbert met Scott-Heron’s mother, Robert Scott, who was named for her father and called Bobbie. “It was after the war, working for Western Electric,” Scott-Heron told me. “He also played for the Chicago Maroons, or something like that. A Scottish team came through, and he scored on them, which was not what they had come for. They was all white. He went to Scotland, and the legend goes he scored the day he arrived. He was dubbed the Black Arrow, and played professionally for three more years.”

Scott-Heron’s parents separated when he was two years old, and while his mother went to Puerto Rico to teach English he lived with his grandmother in Jackson. “My grandmother was dead serious,” he said one day, sitting on his couch. “Her sense of humor was a secret. She started me playing the piano. There was a funeral parlor next door to our house, and they had this old piano that they used for wakes and funerals, and they were getting ready to take it to the junk yard. She wanted me to play hymns for the ladies’ sewing circle that met every Thursday, and she bought the piano for six dollars, and she paid a lady up the street five or ten cents a lesson to teach me to play four hymns, ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus,’ ‘Rock of Ages,’ ‘The Old Rugged Cross,’ and I can’t think of the other one. I was eight years old, and I had started to listen to WDIA in Memphis, and they would play the blues. When I was practicing, I would have to mix them, because my grandmother was not big on the blues. When she was out in the yard, I can play what I want, but if she’s in the house I got to mix John Lee Hooker with ‘Rock of Ages.’ ”

The phone rang, but he ignored it. “I found my grandmother dead,” he went on. “It shook me up. I got up to make her breakfast, and I knew it was strange that she wasn’t stirring. I went in to wake her, and she was laying in rigor mortis”—he leaned back and held his legs and arms stiff—“and I’m done. I called next door, and the kid picked up the phone, and I was so wild, he dropped it. I went outside and saw the woman from the house going to work, and she came and took over. I was twelve.”

With his mother and her brother, Scott-Heron moved to an apartment in the Bronx, and his mother went to work for the city housing authority. Before long, his uncle moved out, and his mother couldn’t afford the rent, so she put her name on a list for an apartment in a project in Chelsea, in Manhattan. “Black people didn’t want to live in Chelsea, but we just wanted to go somewhere,” Scott-Heron said. “We started in ’65. It was eighty-five per cent Puerto Rican, fifteen per cent white, and me.”

The young woman who taught Scott-Heron English in his sophomore year at DeWitt Clinton High School had gone to a private school called the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, which is in Riverdale, a prosperous section of the Bronx. “She was assigning all these books that didn’t mean anything, like ‘A Separate Peace,’ ” Scott-Heron said. “Finally, she asked me a question, and I said, ‘Look, can I get out of here? This just sucks.’ I told her—I figured she knew—‘I can write better than that. I been sitting here writing better than that.’ I handed her something from my notebook, and she gave it to the head of the department at Fieldston. They asked me would I come to a meeting. I said I might walk out, but we met at the Howard Johnson across from the Bronx Zoo, and I got a hamburger and a strawberry shake out of it, while they asked me would I take a test to see if I could go to their school.”

After he took the test, the school asked him to another meeting. “They looked at me like I was under a microscope,” he said. “They asked, ‘How would you feel if you see one of your classmates go by in a limousine while you’re walking up the hill from the subway?,’ and I said, ‘Same way as you. Y’all can’t afford no limousine. How do you feel?’ Anyway, it just happened to be the day that my mother was sabotaged by this diabetes. We took a break, and I called my uncle at the hospital, and he told me, ‘Come down here,’ so I went back to the meeting and I said, ‘Whatever you’re going to decide, you decide, but I have to go and be with my mother.’ From the way I handled it, I learned later that they thought that this was a sign that I was mature enough to handle whatever would come my way from the school.”

Scott-Heron was one of five black students among a class of a hundred, and in his second year he got in trouble for playing the piano. “They had a beautiful Steinway they used for the choir and the chorus, but I got caught using it to play the Temptations,” he said. “A guy came in and screamed at me to stop, and they put a sign up saying ‘Do Not Play.’ A few days later, he came in, and I’m sitting under the sign playing the piano. So they told me they were going to call my mother, and I laughed—not because I was being disrespectful, although he took it that way—but because I thought, You really don’t want to get my mother into this. But they called her and told her to come to a disciplinary meeting, and the evening before she asked me what had happened, and I told her. And she said, ‘Well, did you hit the man?,’ and I said, ‘No, I was playing the piano.’ I tried to explain that there had been no rule against it until I did it. A lot of kids had been going up there to play ‘Chopsticks,’ I said, and she asked me again, did I hit him. She had reached the conclusion that I had done something so awful that I didn’t want to describe it, because she couldn’t imagine that they had called her up there to tell her I had been playing the piano.”

The meeting took place around a horseshoe-shaped table. “My mother listened to them, and when they were finished she said, ‘You all know where we live, and the difficulties of our life, so I’m not going to talk about that. We got burglaries, assaults, muggings—it’s not the best place to raise a child—but whenever something happens down there that might involve my son, I don’t call you. I figure that’s my area, and this is yours. Now, I have read your discipline handbook, and what I suggest you do is expel him, because it’s this way or that, near as I can tell, so what I’m going to do right now, since this is your area, I’m going to leave and go to work, because if I don’t get there soon, they’re going to take half my day’s wages from me, and when I get home this evening he’ll tell me what you decided, but, if you’re asking my opinion, you have to expel him. We have really enjoyed it here, and it has added to my son’s life, and I think we’ve added to your ethical-culture thing, but I’m going to go now, and you’ll excuse my son because he’s got to walk me to the subway. Thank you all very much.’ She got up and put on her coat, and I took a hard look at the man who had started all this, to say, ‘See, I told you you didn’t want to get my mama involved.’

“She walked to the subway in a stone silence. All she said was ‘I want you to leave these people’s piano alone. You’re not here to play the piano.’ I said, ‘What if they expel me?’ ‘Then you won’t have to worry about it; you’ll be someplace else. You leave these people’s stuff alone, and when you tell me something from now on I’ll believe you.’ ”

Scott-Heron was made to stay after school three Wednesdays in a row to wash out the brushes in the art room. A classmate, Roderick Harrison, says that he remembers two things about Scott-Heron. “He could hold a classroom or a hallway in thrall” is one of them. The other recollection is of his mother. “She was,” he told me, “imposing.”

t the end of June, at a concert in Central Park, Scott-Heron played one song from his new record, the rhythm-and-blues standard “I’ll Take Care of You,” but for the rest of the concert, as is customary with him, he drew from his older catalogue. Later, he was joined by the rapper Common, who said that as a child in Chicago he had listened to Scott-Heron and that it was an honor to occupy the stage with him. Then Common began to rap, but stumbled because the pace was too fast. He asked the musicians to slow down, then he asked them to go even slower, and then he started again, sounding not quite so agitated and more earnest. The song he recited was called “My Way Home,” which includes samples from Scott-Heron’s “Home Is Where the Hatred Is.”

“We been sampled,” Scott-Heron told me. “I don’t want to tell you how embarrassing that can be. Long as it don’t talk about ‘yo mama’ and stuff, I usually let it go. It’s not all bad when you get sampled—hell, you make money. They give you some money to shut you up. I guess to shut you up they should have left you alone.”

The epithet “godfather of rap”—derived from the claim that Scott-Heron originated the form—is partly apt but also partisan. The case for him as proto-rapper goes like this: at the beginning, he had company, the Last Poets, who in the late nineteen-sixties in Harlem recited poetry while accompanied by conga drums, used mainly in Afro-Cuban music. “Compared to Gil, their stuff is very stripped down,” Bill Adler, the hip-hop critic, curator, and record executive, told me. “It was like a park jam that got onto a record. Nothing but beats and rhythms. They embodied a revolutionary idea of black manhood, and Gil likewise. He wasn’t as potent as they were—he was more musical—but at the very beginning you can think of Gil Scott-Heron as a one-man Last Poets. People often confused the two, or thought that he was a member of them.”

Scott-Heron went to Lincoln University, the historically black college in Pennsylvania that Langston Hughes had attended. The Last Poets performed there in 1969. “Gil was the student-body rep,” Abiodun Oyewole, one of the Last Poets, told me, “and after the gig he came backstage and said, ‘Listen, can I start a group like you guys?’ ”

A strict honoring of rap origin legends would say that it begins with d.j.s in the Bronx, among African-Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Jamaicans, in the summer of 1973, and especially with a d.j. named Kool Herc. The people involved were going to parties where they could dance to a spare form of recorded music that had been arranged so that the pulse was foremost. The language and the stories that went along with them were simple. “Hip-hop has its own superheroic myths and stories,” Greg Tate, the hip-hop critic, says. “Gil is a genre to himself.”

The legacy of the Last Poets and Scott-Heron was more deeply embraced by second-generation rappers with social convictions. Among these was Chuck D., of Public Enemy, who told me that he first heard Scott-Heron when he was a teen-ager, in the nineteen-seventies. Scott-Heron and the Last Poets are “not only important; they’re necessary, because they are the roots of rap—taking a word and juxtaposing it into some sort of music,” he said. “You can go into Ginsberg and the Beat poets and Dylan, but Gil Scott-Heron is the manifestation of the modern word. He and the Last Poets set the stage for everyone else. In what way necessary? Well, if you try to make pancakes, and you ain’t got the water or the milk or the eggs, you’re trying to do something you can’t. In combining music with the word, from the voice on down, you follow the template he laid out. His rapping is rhythmic, some of it’s songs, it’s punchy, and all those qualities are still used today.”

When I asked Scott-Heron what he thinks when people attribute rap music to him, he said, “I just think they made a mistake.”

cott-Heron was one of the first musicians signed by Clive Davis, in 1975, for Arista Records. “I had seen a live performance, where he was very striking,” Davis told me. “Very charismatic, absolutely unique—the verbal and the performing abilities—he was electrifying, and based on his song ‘The Bottle,’ and ‘The Revolution,’ and seeing him, I signed him. He was very compelling as a speaker—the wit, the turn of phrase—it was all very special.”

Between 1975 and 1985, Scott-Heron made nine albums for Arista, and then they parted. “I always felt tremendous regard for him,” Davis said. “You see the success of a Jay-Z or a Kanye West, and I always felt that Gil was as charismatic as either of them. Seeing him in his prime, the ability to dominate a stage—Gil at his best was an all-timer.”

A theme that Scott-Heron often brings up at performances is how people say that he disappeared during the past decade—during the years, that is, when he was serving time. Not long ago, he sold out the Blue Note, a club in Manhattan. “I read all of those reviews that said I disappeared,” he said. “Wouldn’t that be great if I could add that to my act? Come up here and—poof!” Then he said, “I had read how great I was before I disappeared. It makes me afraid to show up.”

When I first began visiting Scott-Heron, he would leave the room at intervals and go into his bathroom. The next time I went to his apartment, he went into his kitchen and a stream of smoke drifted out. One day, I turned around, and he had his crack pipe to his lips, and after that he didn’t bother to leave the room anymore. Sometimes he would fall asleep in the middle of an interview, and I would excuse myself.

Monique de Latour, an artist who lived with Scott-Heron for three years beginning in 1997, says that he would smoke crack for four or five days without rest. The longest she saw him stay awake was seven days. She knew he was getting tired when the things he said no longer made sense. “He would be talking about baseball and say someone had scored a touchdown,” she told me. Periodically, he would disappear—he says he was trying to get away from her. To find him, de Latour would check the phone to see whom the last call had been made to, which was sometimes a clue. If his propane torch was gone, she began visiting the hotels he liked—the Casablanca, on 145th Street, or the Old Broadway, on 126th, or the New Ebony, on 112th, where he was eventually banned for setting fire to his room. He would check in as Benjamin Safir. “As in Ben Safir, as in Been Safer,” she said. The desk clerk had been paid to tell her that he wasn’t there. “I would find a crackhead who didn’t care about Gil and give him half a ripped five- or ten-dollar bill,” she said. “I gave him the other half after I had checked out what he told me.”

Sometimes de Latour found the door to Scott-Heron’s room left ajar and Scott-Heron asleep. She took photographs of him lying on the hotel bed, which she hung in their apartment in the hope of forcing him to face his circumstances, but he wouldn’t look at them. If she didn’t find him in the hotels, she called the neighborhood hospitals and then the police precincts. Not infrequently, she found him locked up for trespassing or loitering. Once he was arrested as Denis Heron, which is his half brother’s name. When he missed a court date, the cops went looking for Denis.

According to de Latour, after a couple of days of smoking, Scott-Heron would sometimes make holes in the walls looking for microphones and cameras. On the door of their apartment, he would post menacing remarks, which he would change every few weeks or months. One said, “For all visitors we despise. I will pray to ‘the spirits’ that you and all who conspire with you condemn your souls. You have been seen. You are known. You will be paid.” He believed that bad spirits came with crack, and to counteract them he would give money to charities.

When he ran low on money from royalties, de Latour says, he would arrange for gigs and insist on a deposit to pay for the band’s airfare. He would spend the deposit, then arrive with a two-piece band, which was all he could afford. When his money ran out altogether, he slept, sometimes for two weeks. “He could sleep until he knew the next check was coming,” de Latour said.

De Latour would try to get him to leave the apartment, because he couldn’t smoke crack in public, but he almost never would. His teeth fell out and he got implants, some of which also fell out—one time while he was onstage in Berlin. “I saw him once at Eighth Avenue and Twenty-third,” Bill Adler told me. “This tall guy staggering across the street, and I recognized Gil immediately—he’s very tall and distinctive—and he’s clearly whacked, and he could have been dead right there, stumbling across the intersection.”

In the fall of 1999, de Latour told him to choose between her and crack, and he chose crack and moved in with his mother, on East 106th Street. She was in poor health, and shortly after he moved in she died. “I went with Gil to the funeral, and he was such a mess,” de Latour says. “He was already going downhill, but he was going more downhill once his mother died.”

After the funeral, he moved out of his mother’s apartment. He ignored the eviction notice the landlord sent him. Her belongings were auctioned.

Even so, de Latour said, there were many moments of tenderness between them. “There is a very gentle person inside Gil,” she said, “but very remote. It’s the little boy who lived with his grandmother in Jackson. He used to say to me, ‘I wish you knew me before I was like this.’ ”

Scott-Heron spent July on tour in Europe. His tour manager, Walter Laurer, says the tour has gone smoothly, and Scott-Heron says he hasn’t used any drugs for more than a month.

Anyone familiar with Scott-Heron’s career knows that early on he had a partnership with a musician named Brian Jackson. In 1969, when they were students at Lincoln, they wrote songs together. Eventually, they made nine records. They parted company in 1979, although they made a few attempts to play together again. “We’ve had a few falling outs,” Scott-Heron told me, “but this last one, I think, is permanent.”

Jackson still records and performs, but he has a day job as a project manager in the City of New York’s I.T. department, where he began working in 1983, when, he told me, “I woke up one morning and realized I wasn’t getting myASCAPchecks anymore for publishing. I called and they said, ‘We don’t have you listed as a recipient.’ I said, ‘I could show you some checks that you just sent me,’ but they said that didn’t matter, and I didn’t have the money for a lawyer to find out what had happened. I sent for the papers to prove that I was a fifty-per-cent partner of Brouhaha Music, and I found that the company had been dissolved in 1980.”

“Somebody should have pushed the mute button on that motherfucker,” Scott-Heron said of Jackson. “Our accomplishments show what kind of people we are. The way our careers have gone, you can see who the spirits favor.” On another occasion, he said, “I would not take a dollar from Brian.”

Scott-Heron says that in 2003 Jackson stole money that was meant to be used for his bail; Jackson says that, after the bondsman refused the money, he used some of it to pay members of the band for shows that were cancelled when Scott-Heron was arrested at the airport. He also paid some of his own bills. Jackson told me that, as Scott-Heron was about to go to jail, they spoke. “I thought it was time to go to him and say, as a friend, ‘Are you O.K.?’ He told me, ‘Yeah, I’m O.K. I’m doing better than you,’ meaning I was the one having to scratch for a living.” In one of the interludes on “I’m New Here,” Scott-Heron says, “If I hadn’t been as eccentric, as obnoxious, as arrogant, as aggressive, as introspective, as selfish, I wouldn’t be me.”

At the Blue Note, when Scott-Heron touched on the subject of prison he said, “They say my new record proves I came out of jailangry. Nobody comes out of jailangry. They come out of jailhappy.” He wore dark trousers and a cap, and a suit jacket with a label that said “Jos. A. Bank” sewn above one wrist. When he finished talking, he sat down at an electric piano, which looked like a desk. His hands formed chords. He began a song called “Show Bizness,” which has the refrain “Do you really want to be in show business?,” then he stopped. “I used to be with Clive Davis,” he said. “I don’t think he liked this song. Not in that key.” He started in a second key. “Show business, want to be in show business,” he sang, then stopped again. “Now I don’t,” he said. He sang the words softly to himself as he searched for the chords, then he started a third time and said, “That’s right, that’s right.” At one moment, he leaned his head back and closed his eyes, and it looked like the expression of an ecstatic.

One of the last times I went to Scott-Heron’s apartment, he rose from the couch now and then to make slow journeys around the room. His movements appeared to have a purpose, for he spent some time opening drawers and meticulously sorting through the prescription bottles and folded-up dollar bills and scraps of paper they contained, but he didn’t say what he was after. When he found a lottery ticket that hadn’t been scratched off, he sat down and carefully ran a coin across its surface.

He was wearing jeans and a black-and-white shirt with the buttons askew. It was the morning after he had been expected at a video shoot downtown to make the second video for “I’m New Here,” and he hadn’t shown up. Meanwhile, the crew and the filmmaker had waited through most of the night. When the phone rang, he said, “That’s those people from the video shoot trying to get me,” and he didn’t answer. “They all think it’s some kind of mixup when I don’t show up where they are, but being too omni-visible is a bad idea. The kids at the record company are very enthusiastic, and they have a lot of friends they have made, and they all want to have an interview, and the only problem is they’re asking the same things people asked me a long, long time ago, because that’s what they do when they’re starting—you ask questions you already know the answer to. I don’t want to disappoint them, but you can’t disappoint unless you have an appointment. They don’t know I only like to talk to people who have something to talk about other than me. Like everybody in New York, they know everything. How can you tell them anything?”

He tossed the lottery ticket on the floor. “It’s the death of the vertical,” he went on. “They have taken all this time to stand up straight so that they can say ‘I.’ They’re very proud of that. The way you get to know yourself is by the expressions on other people’s faces, because that’s the only thing that you can see, unless you carry a mirror about. But if you keep saying ‘I’ and they’re saying ‘I,’ you don’t get much out of it. They’re not really into you, or we, or they; they’re into I. That makes conversation slow.

“I am the person I see least of over the course of my life, and even what I see is not accurate.” The phone rang. “This is Brouhaha Music,” he said. “Who the fuck is this?” He leaned back and talked softly, with his eyes closed and a hand on his forehead. Then he hung up and rubbed his neck with one hand, while turning his head from side to side. “I’m trying to stay out of traction,” he said. “I feel like I got a piece of gravel up at the top of my spine.” He lit the propane torch and touched the glass tube to his lips. “Ten to fifteen minutes of this, I don’t have pain,” he said. “I could have had an operation a few years ago, but there was an eight-per-cent chance of paralysis. I tried the painkillers, but after a couple of weeks I felt like a piece of furniture. It makes you feel like you don’t want to do anything. This I can quit anytime I’m ready.”

He touched the flame to the tube. “I have a novel that I can write,” he said next. “It’s about three soldiers from Somalia. Some babies have been disappearing up on 144th Street, and I speculate later on what happened to them and how they might have been got back. These guys are dead, all three, and they have a chance in the afterlife to do something they should have done when they were alive.” He raised the torch, then paused and said, “I have everything except a suitable conclusion.”♦

>via: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/08/09/100809fa_fact_wilkinson?current...

__________________________

Cité de la Musique - 08/09/2010

More info on this concert and full review of the 2010 La Villette Jazz festival on :

http://vibes4yoursoul.blogspot.com/2010/09/concert-review-la-villette-jazz.html

__________________________

Musicians and friends have been paying tribute to the poet and hip-hop pioneer Gil Scott-Heron, who has died at the age of 62.

Eminem, Talib Kweli and Snoop Dogg were among the rappers who acknowledged his influence after hearing the news.

Public Enemy member Chuck D said on Twitter: "We do what we do and how we do because of you."

Wu-Tang Clan's Ghostface Killah wrote: "Salute Gil Scott-Heron for his wisdom and poetry! May he rest in paradise."

Scott-Heron, often called the Godfather of Rap, died in a New York hospital.

Gil Scott-Heron released his final album, I'm New Here, in 2010

Gil Scott-Heron released his final album, I'm New Here, in 2010

His material spanned soul, jazz, blues and the spoken word. His 1970s work heavily influenced the US hip-hop and rap scenes.

His work had a strong political element, and one of his most famous pieces was The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.

Eminem wrote on Twitter: "RIP Gil Scott-Heron. He influenced all of hip-hop."

Cee Lo Green paid tribute to "the god Gil Scott", while Talib Kweli said he "completely influenced me as an artist".

Politically outspoken rapper Michael Franti said Scott-Heron's talent was his ability to "make us think about the world in a different way".

He would make listeners "laugh hysterically about the ironies of American culture, anger at the hypocrisy of our political system, all to a beat that kept us on the dance floor, with a voice and flow that kept you waiting with anticipation for the next phrase".

Richard Russell, who produced and released Scott-Heron's final album I'm New Here in 2010, described him as "a master lyricist, singer, orator, and keyboard player".

"Gil was not perfect in his own life," Russell wrote. "But neither is anyone else. And he judged no-one.

"He had a fierce intelligence, and a way with words which was untouchable; an incredible sense of humour and a gentleness and humanity that was unique to him.

"Gil shunned all the trappings of fame and success. He could have had all those things. But he was greater than that."

Jamie ByngPublisherFew came away untouched by his magnetism, humility, biting wit and warmth of spirit”

The musician's publisher Jamie Byng remembered him as "a giant of a man, a truly inspirational figure whom I loved like a father and a brother".

Scott-Heron infected people who encountered him with his "singularity of vision, his charismatic personality, his moral beauty and his willingness to take his fellow travellers through the full range of emotions", Byng wrote.

"Throughout a magnificent musical career, he helped people again and again, with his willingness and ability to articulate deep truths, through his eloquent attacks on injustices and by his enormous compassion for people's pain.

"Hundreds of thousands of people saw Gil perform live over the decades, always with remarkable bands, and few came away untouched by his magnetism, humility, biting wit and warmth of spirit."

Lemn Sissay, a friend of Scott-Heron's who produced a documentary on his work, told the BBC he was "a polymath" who "spoke crucially of the issues of his people".

"In the late 60 and early 70s, black poets were the news-givers, because their stories were not covered in truth in the mainstream media," he said.

>via: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-13588317

airplanemaniac1 on Jan 11, 2009

Stephen Bantu Biko (18 December 1946 12 September 1977) was a noted anti-apartheid activist in South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. A student leader, he later founded the Black Consciousness Movement which would empower and mobilize much of the urban black population. Since his death in police custody, he has been called a martyr of the anti-apartheid movement. While living, his writings and activism attempted to empower black people, and he was famous for his slogan "black is beautiful", which he described as meaning: "man, you are okay as you are, begin to look upon yourself as a human being".Despite friction between the ANC and Biko throughout the 70s[quotation needed] the ANC has included Biko in the pantheon of struggle heroes, going as far as using his image for campaign posters in South Africa's first non-racial elections in 1994.

Room Magazine's Annual Fiction, Poetry, and Creative Non-fiction Contest – 2011

Calling all woman writers: sharpen your pencils or fire up your laptop and send us your fiction, poetry, or creative non-fiction contest entries.

Deadline: Entries must be postmarked or e-mailed no later than July 15, 2011.

Entry Fee: $30 per entry (includes a complimentary one-year subscription to Room). Non-Canadian entries: $42 Canadian dollars.

Prizes: 1st prize in each category – $500, 2nd prize – $250. Winners will be published in a 2012 issue of Room. Other manuscripts may be published.Judges:

Fiction: Amber Dawn

Poetry: Elizabeth Bachinsky

Creative Non-Fiction: Susan JubyRules & Details:

Poetry: max. 3 poems or 150 lines | Fiction and Creative Non-Fiction: max. 3,500 wordsMore than one entry will be accepted as long as fee is paid for each entry. No manuscripts will be returned. Only winners will be notified.

There will be blind judging, so please don't put your name or address on your entry submission. On a cover sheet (for mail entries) or in the body of your e-mail (for electronic entries), include your name, address and phone number, as well as the title(s), category and word count of your submission. Entries must be typed on 8.5 x 11 white paper, and prose must be double-spaced. Each entry must be original, unpublished, not submitted or accepted elsewhere for publication and not entered simultaneously in any other contest or competition.

Electronic Entries:

Mail Entries:

Simply e-mail your submission as an attachment to contests@roommagazine.com, pay online using the button below, and we'll take care of the rest. Remember to include your complete contact information in the body of your e-mail. And please make sure that the contact information you give through PayPal is the same as in your entry; use the "note to merchant" field, if necessary.

Send your entry, cover sheet and payment by cheque or money order made out to Room to:

Room Contest 2011

P.O. Box 46160, Station D

Vancouver, BC V6J 5G5

Canada

Call for Submissions - Images, Sound/Music, Video and Literature needed for Online Gallery

Viral Mediaocracy (VMO) - VMO is virtual gallery that will feature curated audio, video, image and text in viral multi-media exhibitions. For this project, creativity will be valued over artistic merit. Therefore, we encourage anyone who believes that they have compelling and thought-provoking content to submit to the site. VMO is for any individual who happens to capture a provoking slice of life, be it a snippet of a conversation, sounds of a bustling city, a written pondering, a haiku, an optical illusion, an astounding sunset...the options are limitless!

Featured works are meant to be experienced not only on the VMO page but other viral manifestations (such as YouTube, Vimeo, SoundCloud, etc.), on both computers and mobile devices. The inclusion of content on this site is based on how well the content addresses the demands of viral technologies. All submitted material should be something that can be experienced in full on anything from a 17" computer monitor to a palm-sized mobile device.

Content is open. All submissions are welcomed!

Please see here for information about submissions.

Also, please do not hesitate to contact us here, for more information about the project.

Thank you, in advance, for your support. We look forward to having you onboard!

Warm regards,

VMO Team

Call For Submissions

Wednesday May 25, 2011 – by Clutch

Clutch, one of the leading online magazines for women of color, is seeking writers to contribute short news and opinion articles to our daily blog.

Do you devour pop culture, the news, politics, health and beauty issues, and have an opinion on almost everything? Are you a great writer who can produce interesting and thought-providing articles? Are you looking to get clips and build your freelance resume? Then we are looking for you!

Interested?

- Visit ClutchMagOnline.com to get a feel for our content, voice, and audience.

- Send a short email about yourself, your writing history, and 2-3 pitches to editors@clutchmagonline.com

Writers will be paid $10-$15 per (250-400 word) published piece.

Here’s one of those times when social media has really proven a blessing. I met Tayari Jones through Twitter, and while I did not know her work at the time, only that she was a working writer, I have come to greatly appreciate not only her writing but also her honesty about the writing process, about challenging discussions, and about life in general. I think you’ll find you appreciate her, too.

Your new book Silver Sparrow has just been released. Can you tell us a little bit about it?

The first sentence – “My father, James Witherspoon, is a bigamist.” – sort of gives a quick description of the story. It’s a novel about two sisters who have the same father. The thing is that Dana knows about Chaurisse, but Chaurisse has no idea that her father is living a double life. I decided to tell the story from both of their points of view because neither of them knows the whole story. Only the reader will.

This book took me five years to write. It was the most emotionally challenging—more so even than Leaving Atlanta, although that subject matter (The Atlanta Child Murders) was of much more intense. I think that the matter of personal betrayal was far more taxing than a sort of excavation of history.

I just had the privilege of reading your first chapter, and I’m most struck by the weight the narrator, Dana, gives to naming things. In fact, she says, “It matters what you call things.” Is that something you as a woman and a writer also believe?

Yes! Language is everything. It reveals what we think, and it guides what we think. For example, an ongoing discussion I have with young people is to stop calling women “female.” It matters that you use a term usually used to describe animals to describe a human being. Call her a woman. Language can strip a person of dignity as well as restore dignity. It can elevate and degrade. I try to be extra careful with language. The one thing for which I have no tolerance in my creative writing workshop is sloppy language. I want my students to search for the perfect words that say exactly what they mean to express. They think I am unreasonable, but I keep on them.

What made you want to write about bigamy? It’s not a topic that comes up in modern society that often (although the show Sister Wives might be changing that), so I’m eager to hear how you came upon it.

Actually, it wasn’t bigamy that drew me to this story. It was the idea of shared fathers. Lots of people have siblings that share just one parent, and it necessarily makes for certain tensions and inequality. I mean, a man can only live in one home. One set of kids gets a full-time dad, and another will not. This is the subject that I really want to talk about, and it’s an ancient conflict in literature, all the way back to the Greek myths and before. The big problem with Zeus was that he had all these half-mortal kids outside his marriage to Hera! And even in the African American tradition, very often slave narratives were stories of the black children of the slave owner who were denied their birthrights as heirs. In modern times the question is sticky. What is a man to do if he has a child outside his marriage? How can he do right by everybody involved? In Silver Sparrow, James decides to marry his mistress, too, and try to keep all the balls in the air which is devastating to everyone involved.

What is your writing process like? What was the process of writing Silver Sparrow like for you?

Slow! Actually, I am a fast writer and a slow writer at the same time. My mentor, Ron Carlson, used to say that some people are ekers and some a gushers. Ekers are the ones who spend hours and come up with only a couple sentences. I am a gusher. When I type, it sounds like someone is firing a machine gun. BUT, only about 5% of what I write is usuable. So I just write and write and write until I end up with something good.

Your book tour has just begun. What is the experience of reading your own work and talking about it like? Do you take energy from that process or is it more draining than anything? Or maybe it’s both?

I love meeting readers. Yes, it’s draining going from city to city, and a person gets tired of hotel food—but it’s such a job to meet people who have read my books. When I write, it can be like sending a letter in a bottle. It’s such a thrill to know that it reached someone.

On your blog, you give great writing advice – I especially like “The Lucky Charms Method for First Drafts” – so if you have to give three “tips” for writers, what would you say?

It’s a hard question, because it’s like giving beauty tips—it really depends on what the issue is. But there is one thing:

Stop censoring yourself when you write. If you want to censor, do so when the draft is done, but when you censor as you create, you will keep from accessing the best part.

Thinking again about Silver Sparrow, where did the seed for this book come from? Was there a moment when you had a story or character come fully into view?

When I write a novel, I imagine a world. The characters don’t really show up one by one. Instead, they tend to come to me as sort of ghostly figures, and their features become more clear as a write– like a Polaroid developing.

I know it’s probably way too early to ask this, but I can’t resist asking if you have a “next” project in mind. Or are you totally dedicated to Silver Sparrow and need to keep your focus there.

I have a new project in mind, and it’s really intense. I am afraid to even talk about it, but it is something that has been on my mind since I was seventeen years old.

If you could recommend five books that the readers of my blog should not miss, what five would you recommend?

Everyone should read every book that Toni Morrison has ever written. Really. But start with Song Of Solomon. Those are the only books that I feel that everyone in the world should read. But here are some titles I have read recently that I liked—Miles From Nowhere by Nami Mun, Say Her Name by Francisco Goldman, Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Adichie and Butterfly Boy by Rigoberto Gonzalez.

I am deeply honored that Tayari granted me this interview. Be sure to pick up a copy of Silver Sparrow; definitelycheck out her blog; and join me in following her on Twitter. Plus, she’s on tour, so be sure to visit her tour schedule and go see her loveliness in person if you can.

++++++++++++++++++++++

I’m a teacher, a writer, an editor, and a reader. I teach creative writing, composition, professional writing, and developmental writing (read- grammar.)

I also write creative nonfiction and sometimes get something published. Most often I just get rejection letters that I dutifully file because some day I’ll be able to make my own recycled paper house from crushed up and hardened rejection slips.

During my free moments, I practice yoga, not as regularly as I should. I also crochet, cross-stitch, and spend far too many hours onEtsy admiring the things paper can make.

My mother passed away this past Thanksgiving, and I have lost my best friend. But now I have the blessing of living with my dad and building an even better friendship with him. My beautiful brother maintains this great website for me, a feat which I’m sure prompts his gorgeous wife to give him frequent massages and acupuncture treatments. (Did I get everybody in and include a positive adjective for everyone?)

That’s me. So if you have more personal questions, think carefully about whether you want to know the answers, and if you still do, write me at andilit@gmail.com or use this form.

Thanks for reading.

Andi

Photo by Brittany Jones Photography