Haiti, Violated

By Clancy Nolan

PORT-AU-PRINCE—When the earthquake struck Haiti last January, a lanky 26-year-old woman, who asked to be called Rolonda, gathered her belongings and moved with her mother, her brother and her five-year-old daughter into a field where they would be safe from the aftershocks and falling debris of the capital’s crumbling buildings. Rolonda strung up a pair of bed sheets for shelter.

It was 7 o’clock in the evening, two days later, when the gang of men passed through her camp, armed with guns. Her family watched in horror as Rolonda was dragged away, screaming. No one tried to help. They forced Rolonda into an abandoned building and tied her up. At least a dozen men raped her that night, and every day after, for four days.

“I can recognize 10 of the men who raped me,” she says. Sitting in an office at a small law firm in Port-au-Prince, Rolonda speaks at barely a whisper, her almond-shaped eyes locked on the floor. “I wasn’t the only woman in that building,” she says. “I could hear other women screaming.”

When the men finished with her, Rolonda was released. She walked through the horror show that was Port-au-Prince in the weeks following the quake. She didn’t go to the hospital. She was too ashamed. And anyway, the hospitals were crumbling wrecks. She didn’t try to find a doctor. Doctors were amputating people’s limbs in the street. She didn’t go to the police. What police?

The men who raped her bragged about escaping prison when the walls started to shake. She had no place to go but the very same camp she had been taken from four days earlier, where she now found herself a spectacle. People pointed as she walked past.

By December, almost a year later, Rolonda and her daughter had settled into a small home in Grand Ravine, one of the hillside slums on the south side of Port-au-Prince, in an area known as Martissant. Life was getting better, she says. A week before Christmas, Rolonda’s boyfriend brought food and money to help with their daughter’s care. While he played inside with their daughter, Rolonda stepped out to shower. She threw a towel over her shoulder, grabbed a bucket of water, and headed outside. It was dark, so it took a moment to notice the two men standing on either side of the front gate. She assumed they were from one of the gangs that operate with impunity inside Grand Ravine. She didn’t run. If she fled, she reasoned, they might think she was hiding a rival gang member. Rolonda asked quietly if she could pass. “Yeah, it’s okay,” said one of the men. “Go ahead.”

She walked to the spot where she usually bathes, in a secluded area behind a nearby staircase. She quickly poured a few cups of water from the bucket over her body, but she was nervous and picked up her bucket to go home. She realized the men were still lurking around the corner. Then she noticed a third man. One grabbed her by her panties, and stuck a gun into her waist. “If you scream, I will shoot you,” he said.

“The whole time he was holding me with the gun, he was touching me, sticking his fingers inside me,” Rolonda says. “They didn’t wait to reach my house before they started using me for sex.”

The men took turns raping her. Then they forced their way inside her house, ordering the small family onto the ground. They ransacked the place, stealing everything of value: cell phones, a portable DVD player, and the odds and ends Rolonda peddled for a living.

She doesn’t know how long she laid facedown on the floor. Her daughter eventually fell asleep next to her.

Afterward, she sought help. She went to a hospital, where she received a course of antibiotics and an HIV prophylactic. There’s no DNA database in Haiti, no rape kit. But Rolonda asked for a medical certificate. Signed by a doctor, the certificate details the attack and the victim’s age and injuries—sometimes noting whether she was a virgin or not prior to the rape. Most of the time, victims wait days or weeks before receiving the medical certificate, which is needed before prosecuting a rape in Haiti.

Rolonda says she doesn’t know the men who raped her in December. She says she doesn’t recall their faces. But their voices haunt her. She has moved to a new neighborhood since the rape, where she is staying with friends, but she doesn’t know how long that arrangement will last. Strange men have threatened members of her family in recent months. Don’t go to the police, or you will pay. “I feel like God is punishing me,” Rolonda says.

VIOLENCE, PAST AND PRESENT

“That is the point where most cases stall,” says Annie Gell, a lawyer with the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux, a human-rights law firm in Port-au-Prince. Practically speaking, if a woman cannot or will not identify her attacker, she has little recourse. Gell, a young, Columbia University-educated lawyer, sits next to Rolonda in the dim office with cracked walls. The firm, which is backed by the Boston-based non-profit Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti, started its Rape Accountability and Prevention Project in June. Since then, Gell and other lawyers have opened more than 60 cases.

Six have resulted in an arrest, but none have gone to trial. In each of these cases, the victim identified her attackers or the police captured them during or immediately after the assault.

“Ninety five percent of the time, these kinds of cases do not get solved,” says Sandy François, director for the defense of women’s rights for the Haitian Women’s Ministry. “No justice is done for these women, and if these people don’t find justice, then why should they talk?”

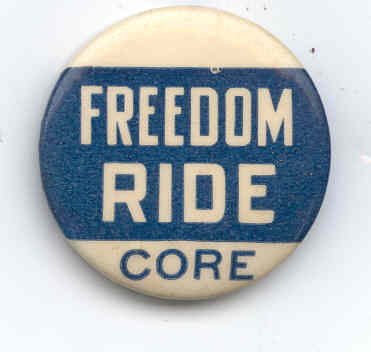

This is not a new problem in Haiti, where it seems as though rape has been committed with astonishing impunity for decades—even becoming a relatively common method of political leverage during the country’s frequent periods of upheaval. Ironically, it was after women finally gained equal suffrage, in the 1950s, that they faced the cruelest state-sanctioned violence. Among his many terror tactics, including murder and torture, the dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his Tonton Macoutes militia used rape to silence opponents of his regime. His son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who ruled until 1986, continued this practice. Later, during the coup d’états that forced Haiti’s President Jean-Bertrand Aristide from office in 1991, and again in 2004, rape was used by the military, police and the paramilitary group Front pour l’Avancement et le Progrès Haitien, or FRAPH, to intimidate and silence Aristide supporters.

The scenario was always the same: “Armed men, often military or fraph members, burst into the house of a political activist they seek to capture,” a U.N. report reads. “When he is not there and the family cannot say where he is, the intruders attack his wife, sister, daughter or cousin.” Former Haitian Supreme Court president André Cherilus said in 1994 that it was “not worthwhile for the victim of rape to go to the police to report the crime….given the extremely high probability of retaliation.”

Still, it’s impossible to separate rape from the broader context of gender inequality in Haiti, argues Gina Ulysse, a Haitian-born professor of anthropology at Wesleyan University. “Women have secondary status, and that goes all the way back to pre-independence,” she says. In fact, until 1979, married women in Haiti were considered legal minors.

Today, women have less access to Haiti’s costly education system, as parents choose to send their sons to school before their daughters. All this means that women are exposed to higher rates of poverty and violence, says Mark Schuller, an anthropologist at the City University of New York.

Until recently, rape was defined in Haitian law as a “crime against morals,” an attack on a woman’s honor. Rapists were more likely to face a financial settlement than jail time. Sometimes a judge would order an attacker to marry his victim. Even the United Nations, which has played a major role in governing the country since 2004, has not been immune to allegations of abuse. U.N. peacekeepers were accused in 2005 and 2006 of raping young women in the cities of Gonaïves and Léogâne.

“We don’t have a culture of denunciation, because we don’t have victim or witness protection,” says Florence Elie, Haiti’s ombudsman. “People are very uncomfortable about going to the justice officials, so most of these girls go back home with no solution.”

Rape finally became the equivalent of a felony in the summer of 2005, by presidential decree. The change was thanks largely to the activism of women’s rights groups in Haiti that pressured the U.N. and the Haitian government to adopt stricter laws against rape. During domestic violence and rape trials, rights groups filled courtrooms with women who sat in silent protest of the status quo.

Their tactics worked. Those found guilty of rape or sexual assault can be sentenced to 10 years in prison. Penalties are more severe when the victim is 15 or younger.

Later in 2005, the Women’s Ministry published a national action plan for strengthening Haiti’s laws against sexual violence and improving treatment for victims. It also eventually established a database of sexual assaults.

But this modest progress was wiped out by the earthquake. Since the quake, the sexual-assault database has not been used. Many of the police officers trained in gender-based violence procedures died during the quake, as did the founders of prominent women’s rights organizations. And, like most government agencies—including the Police Nationale d’Haïti—the Women’s Ministry is still largely operating out of temporary trailers in its front yard.

NO RULE OF LAW

Haiti’s population was in crisis long before the earthquake, with an estimated 70 percent unemployment rate and more than half the country living in abject poverty. When the earthquake hit, roughly two million of Haiti’s 10 million inhabitants were left homeless, and the estimated damages exceeded the country’s GDP. The poorest Haitians ended up in relief camps with few options. Government-funded food aid ended in April 2010. A year later, the tents and tarps are beginning to unravel. And the Geneva-based agency that presides over the camps, the International Organization for Migration, has conceded that “hundreds of thousands” of Haitian will remain in these camps at least into 2012.

These conditions are an all-too-familiar recipe for widescale sexual violence. After the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, hundreds of Sri Lankan women and girls were raped by the very people who rescued them, and later by men in relief camps. In the United States, at least 50 women and girls in New Orleans reported being sexually assaulted in shelters and public places during the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Non-profits and aid agencies have produced reams of reports about the epidemic of rape in post-earthquake Haiti. Amnesty International, the International Rescue Committee, UNICEF and others have sent researchers and lawyers to Haiti’s sprawling tent cities to investigate. Like similar reports from conflict zones such as Darfur, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, they return with horrendous stories: two-year-old rape victims, 70-year-old rape victims, men slashing their way through tents with box cutters and raping daughters before their mothers’ eyes. Last summer, part of a woman’s tongue was bitten off during an attack in a Port-au-Prince camp.

“In whatever situation—whether it’s a cyclone or a coup d’état—out of all these disasters the first people to feel a backlash is women,” says Sandy François of the Women’s Ministry. “The women go to camps, often they’ve lost their husbands, or a valuable man in their family, and that makes them more vulnerable. In some sense, rape becomes a crime of opportunity.”

But the rape crisis in post-earthquake Haiti seems particularly severe, owing primarily to the almost total lack of security or rule-of-law mechanisms. There is no security force patrolling the 1,150 camps in and around Port-au-Prince on a daily basis. Although the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) has a presence in some camps, they rarely patrol. Officers of the Police Nationale d’Haïti reportedly stay mainly on the perimeter of the camps. Both organizations have said they lack the manpower to police the camps reliably. Police chief Mario Andresol says he has reinforced police units to combat gender-based violence, but admits it’s not enough. “As no security effort is 100 percent effective, it is more than probable that rapes will continue to be reported despite our efforts,” he says.

Security is further compromised by the fact that basic services for Haiti’s homeless are almost non-existent. Schuller, the anthropologist, conducted a survey that found that 30 percent of the camps had no toilet facilities. Another survey found that the average of number of people sharing a toilet in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area was 273. Toilets are often set apart from camps, and at night men often hide inside or near the latrines, lying in wait. Separate bathing facilities for men and women are even rarer, and most people must take bucket baths well in view of other camp residents.

Conditions of this sort have contributed to what most experts agree is a rape epidemic in Haiti. Yet the evidence is largely anecdotal, and reliable statistics are scarce. From January to June 2010, the group Haitian Women’s Solidarity (Solidarité Fanm Aysiyen, or SOFA), documented 718 cases in its Port-au-Prince clinics. This January, the grassroots women’s group Komisyon Fanm Viktim pou Viktim (The Commission of Women Victims for Victims, or KOFAVIV), had counted 640 cases of rape since the quake. According to Refugees International, the number of sexual assaults has tripled in the past year. Police chief Andresol, however, says that only 181 women reported a rape in 2010. Out of those cases, 64 attackers have been arrested, he reports.

Sian Evans directs a U.N. committee on gender-based violence that is supposed to coordinate efforts between Haitian agencies, grassroots organizations and various international groups. She grimaces when asked how to find accurate data on the level of sexual violence.

“I don’t think you’re going to find any,” she says.

Indeed, one reason for the lack of data is that most victims have little contact with the criminal justice system. “Of the rapes that I know about personally—meaning I have spoken with the family, seen the victims—none of those have entered the legal system,” says Aleda Frishman, an attorney and executive director of We Advance, a Port-au-Prince-based non-profit focused on women’s issues. Frishman says she’s worked with about two dozen victims. One of them was a four-year-old girl who Frishman recently helped place in a hospital. The girl was raped months ago. She has not spoken since, and recently reverted to diapers.

EVERYTHING LOST

Delourdes Joseph is 38 years old, tall and thin, with graying hair and a broad smile. She grew up in Grand Ravine. She was raped at the age of 17 and shipped off to the provinces to give birth to a son. She returned and was raped again two years later, in 1991.

“Where are the photos of Aristide?”

That’s what the men asked when they burst into her home, suspecting her of supporting the deposed President. They beat her and raped her. “It didn’t matter whether you had any photos,” she says.

When the earthquake hit Haiti last January, Delourdes was living with her husband, Samuel, and her five children in a home near Grand Ravine. The afternoon of the quake, she was feeding her two youngest children under an awning of her home. Her husband was inside napping. All of a sudden she heard a rumbling: da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da. Her first instinct was to grab the children and run. But as soon as she became conscious of what has happening—earthquake!—she started back into the house to wake her husband. She took a few steps toward the modest home before it collapsed. She can’t afford to have the rubble removed.

“To this day my husband is still in that house,” she says.

Shortly after the earthquake, Delourdes was raped for a third time. She was camping in a field in Martissant. She heard a man behind her, and opened her mouth to scream just as he clamped a hand over it.

Delourdes has lived in a tent for the past year. She volunteers for KOFAVIV, an organization formed in 2004 by a group of Port-au-Prince women who were raped during the 1991-94 military dictatorship that deposed Aristide. KOFAVIV dispatches volunteer “agents”—women who help rape victims get to the hospital, to the police, to a lawyer, and to KOFAVIV for group therapy. Men have harassed some agents, threatening them with retaliation for helping victims.

Last June, a prominent Haitian women’s-rights activist testified at a hearing about the rape crisis held by the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva. When she returned to the relief camp where she lived, she was harassed and threatened by men who demanded money, assuming she had resources because of her travel. She and several other activists in that camp eventually fled, sleeping for a time in the driveway of the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux.

Many KOFAVIV agents now work “undercover” in the camps where they live. If an agent hears that a woman has been raped nearby, she discretely texts a contact at KOFAVIV, who then reaches out to the victim.

Delourdes acts as KOFAVIV’s agent in Grand Ravine. On a recent visit to the area, she wears a simple red-and-white polka dotted dress, her fingernails tipped with red polish. As soon as she climbs out of the car, at the end of a cobblestone road, an elderly woman grabs her and kisses her. This is Delourdes’ neighborhood, and although she doesn’t live here, she’s still a community leader.

A mostly dry riverbed runs alongside the base of the neighborhood. PVC pipes pump water out onto the ground, where children bathe and residents fill up five-gallon buckets to lug up dirt paths to their homes. Survivors of the quake have cobbled together small structures by scavenging from the rubble. Three or four families will crowd into a windowless 200 square-foot space at night to sleep. Others sleep outside, under improvised lean-tos.

In Grand Ravine, there are few of the USAID and UNICEF tarps that blanket much of the capital. Because of rampant violence, Doctors Without Borders has a temporary no-go policy for this neighborhood. Two days earlier, violence erupted and at least one man was killed in a shootout with police.

In 2008, the United Nations estimated that almost half of the young women living in violent slums like the Cite Soleil and Martissant had been raped. And a year into the earthquake crisis, the line between “slum” and “relief camp” is increasingly blurry. Gang members, including many of the estimated 4,000 prisoners who escaped during the quake, have moved into various relief camps, which often provide a higher level of anonymity than their old neighborhoods.

Delourdes comes here two or three times a week, holding community meetings, passing out whatever supplies she has, and searching for rape victims. When she hears about an attack, she’ll find the woman or girl, and take her—via tap tap, the elaborately painted pickup trucks that serve as public transportation—to a clinic, to a lawyer, and to KOFAVIV for psychological counseling, usually in the form of group meetings.

“I tell them that their life is not over,” Delourdes says. “I say, ‘You are young and you are here, and life goes on.’”

Delourdes and I walked to the top of one hill and into a small one-room building where more than 30 people have gathered. Grand Ravine doesn’t see many journalists, so an occasion has been made out of our visit. We are directed behind a long table at the front of the room. Someone has placed a flawless white crepe paper tablecloth over it. Obviously meant for a little boy’s birthday party, big orange basketballs make their way around the edges.

The building has served as both a church and a schoolhouse. Paint peels off the two-tone green and pink walls. One by one, people stand up to talk about life since the earthquake.

“I used to be a merchant, and I lost all my merchandise in the quake,” one woman tells the group. “Now I have nothing.”

“I have nothing to eat,” a man says. “At night, if I cannot find food, I pour salt into some water and feed it to my children.”

Everyone complains about the gangs. It’s too dangerous at night to sleep, they say. There are no schools where they can send their children. They want to rebuild their homes, but they have no money to do so.

After a few minutes, Delourdes opens her purse. She pulls out a cheap, red plastic flashlight and a handful of water purification tablets. She hands the flashlight to a woman in the front row. “I’m giving this flashlight to her, ‘cause I know she really needs it,” Delourdes says, smiling apologetically. She passes out the tablets to the group, but there aren’t enough to go around.

“I just bring whatever I have,” Delourdes says.

WHISTLES AND FLASHLIGHTS

When you ask what will prevent rape in Haiti’s camps, people usually say two things: lights and security. A flood light, one aid worker says, is as good as 40 policemen.

But even where lights exist, electricity in Haiti is unreliable, and camps must run generators to keep the lights on overnight. On a recent visit, one American non-profit found plenty of lights in the Place Sainte-Anne camp, in the heart of Port-au-Prince, but the camp managers had no fuel to keep them running. The U.N., Sian Evans says, has helped erect at least 125 lights in camps over the past year. It’s a start, but there are 1,150 recognized relief camps in and around the capital, and this number does not include the smaller, informal groupings of tents in the medians of roads, between buildings and in backyards. Other initiatives focus on training camp managers, police and grassroots organizations on how to deal sensitively with gender-based violence and how to shepherd women through the medical and legal system.

Grassroots groups like KOFAVIV, as well as international NGOs, have passed out thousands of rape whistles. Based on the idea of safety in numbers, women are supposed to blow the whistles if they are attacked. Other women hear it, blow their own whistles and start running. By the time a large group shows up, a rapist will be frightened off. It’s a strategy proven to work, say aid groups.

In the absence of reliable security, camp leaders and NGOs have organized their own makeshift patrols.

In Grand Ravine, Delourdes says, community members recently organized a group of 20 men into an ad hoc security force. With help from KOFAVIV, she gave each man a flashlight, and they agreed to patrol at night. They have already saved one girl from rape, running off her attackers. The men would like food, or rum, or some kind of payment for their patrolling, Delourdes says. But, right now, they’re doing it for free. Another group plans to recruit men who live in a downtown relief camp and who would be willing to work in return for a flashlight, a small monthly stipend, and maybe even pink spray paint—to mark a rapist if they find him attacking a woman.

These tactics work, and are easily implemented on a small budget. But it’s clear that Haiti’s poorest men, women and children will not be safe until they are out of camps and into their own homes. And that is not likely to happen soon. Only about 43,000 temporary shelters (of a planned 111,000) have reportedly been built. And the international NGOs that plan to build such shelters have been criticized for holding onto money raised for Haiti. The Chronicle of Philanthropy reported in January, for instance, that the Red Cross has raised $1 billion worldwide, but has spent less than $300 million so far.

MOVING IN

The choking, gridlocked drive to Delourdes’ new home takes more than an hour, even though it’s only a few miles from the city center. Down a narrow, pot-marked dirt road, her home is a single-story concrete house behind a concrete wall. A spare metal gate in front bears a green stamp that means it’s habitable, that it survived the earthquake. Inside, Delourdes shares two simple rooms with her five children, her sister, and her sisters’ children. They are living together for the first time in a year.

It’s been a week since she moved in, but the inside is nearly empty, aside from a few clothes neatly hung on a wooden rack. In one room are three white plastic chairs borrowed from a neighbor, and a single cot. This is where Delourdes sleeps. In the second room, a folded carpet provides bedding for the rest of the family, unrolled over the concrete floor each night. There’s no indoor plumbing, but there’s a well just a block away, not too onerous a walk with the bucket. And the house is wired for electricity; a bare light bulb is bolted to a two-by-four ceiling beam.

Even after a year of living in tents—flooding when the rains came, baking in the heat the rest of the time—moving into a real home was painful for Delourdes. “It brought back memories of my husband,” she says. “He was my whole life.” To make peace with herself, she walked back to the collapsed home they shared. “I said a prayer, and now I feel more comfortable about living in the house,” she says. “When I entered the house the first time, I told him, ‘Whatever happens, it was written by God.’”

Delourdes is lucky. A group of American lawyers helped pay for this home. But she is literally one in a million. There is no immediate hope for the estimated one million people living in Port-au-Prince’s tent cities. The government and many aid groups want to move people to their old neighborhoods, and build new homes in empty spaces around the city. But most such efforts have been stymied by the difficulty of proving land ownership. Owners of the land used for relief camps are increasingly asking for compensation or for the squatters to leave.

Haiti’s reconstruction has barely begun. Despite the $1.4 billion that private American donors pledged to Haiti last year, and the estimated $10 billion the country expects to receive in global support, poor women find themselves with few resources to protect themselves and their families.

At dusk, Delourdes rides back into town, heading to a job laundering clothes. It’s unclear whether the electricity is out (as it is most every night) or whether there are simply no streetlights (there rarely are) on the stretch of road she takes into town. But there are plenty of lights blazing around the ruined National Palace. Along the chain-link fence in front of the palace, the government has fastened huge posters with computer-rendered images of public works projects and tony apartment buildings they claim will be built in a nearby neighborhood. They have that too-good-to-be true look of advertisements for luxury apartments. Across the street is the Champ de Mars camp, probably the most photographed of the camps, thanks to its proximity to government buildings and a couple of hotels where journalists stay.

Just past the camp, Delourdes climbs out of the car. She did the wash yesterday, now she’s going to iron. “If the power comes on tonight,” she says, eyes rolling, and slips into the night.

*****

*****Clancy Nolan is a journalist based in Toronto whose work been published in Condé Nast Portfolio, the Wall Street Journal, and New York magazine.

(Photograph by Clancy Nolan)

Spring 2011

Almost three years since the financial crisis upended the global economy, it still seems possible that the Great Recession will define this century, just as the Great Depression defined the previous one. Lately, however, hopes for Recovery have replaced the darkest fears of Recession. Paths have begun to appear out of the deep wilderness of despair. How fragile is our recovery? How vulnerable is it to new shocks—and how might those be prevented? With stories and analysis from China, Russia, Brazil, Australia, India, Spain and elsewhere, the Spring 2011 issue of World Policy Journal looks around the world for green shoots that could lead to a promising future, while at the same time considering some cautionary tales.

Elsewhere in the magazine, feature articles explore the interactions between Afghan villagers and Americans soldiers in the Korengal Valley; a rape epidemic in post-earthquake Haiti; the growing power of Russia’s intelligence services; a land grab in Africa; the ongoing conflict in Cyprus; the battle for the Amazon; and the future of Europe.

•••

•••

UPFRONT

Big Question: Paths Out of the Wilderness

World Policy Journal asks a panel of global experts to weigh in the most innovative approaches to spurring or sustaining the global economic recovery. Featuring Esther Duflo, Emmanuel Asmah, Timothy A. Wise and other leading thinkers.

Map Room: China in Africa

Surveying the breadth and depth of China’s often-controversial investments in Africa

We Are What We Measure

The financial crisis revealed, and was in part due to, the limitations of the economic data we have relied on since the Great Depression. Matthew Bishop (the New York bureau chief of The Economist) and Michael Greenargue that we need statistics that contribute to a richer debate about the state of our societies and the choices we face—not numbers that reduce reality to the point of distortion.

Anatomy of a Crisis: Ireland’s Agony

Unpacking the financial collapse of the Emerald Isle

Recovery Under the Banyan

Gandhi would have understood our current mess—and some of his ideas could help us out of it. Econo-philosopher Rajni Bakshi explores what Gandhian thought might tell us about the true meaning of “recovery.”

RECOVERY

New Capitols of Capital

Do Shanghai, Moscow, and São Paulo have what it takes to become global financial centers? Andrew Galbraith, Miriam Elder, and Jeb Blount weigh the strengths and weaknesses of their respective cities, each of which is positioning itself as a potential rival to New York, London, and Tokyo.

A Conversation with Justin Yifu Lin

China’s Justin Yifu Lin, the first chief economist of the World Bank to hail from a developing country, believes the world must move beyond Keynesian models of economic growth and stimulus. He explains his vision in a conversation with the editors of World Policy Journal.

The Luckiest Country

How did Australia avoid the global recession? In a word: China. Australia’s natural resources—especially its coal—fueled China’s growth for the past decade. Michael Stutchbury, economics editor of The Australian, considers whether the rewards Australia reaped are sustainable, and whether the country’s increasingly divisive politics will threaten its economic good fortune.

The Pain in Spain

Nearly five million Spaniards—20.3 percent of the workforce—were unemployed in 2010. Among them are the 15 percent of those between the ages of 16 and 24 who neither work nor study. Yet this ni-ni generation—short for ni estudian, ni trabajan (“they don’t study, they don't work”)—is just one casualty of Spain’s unemployment crisis. Borja Bergareche, the digital editor of Spain's ABC, reflects on how joblessness is corroding the very character of the nation.

PORTFOLIO

Into the Korengal

Photojournalist Tim Hetherington chronicles what happened when American soldiers built a small outpost deep in Afghanistan's isolated Korengal Valley. As the lines between combatant and civilian blurred, American efforts to build trust were undermined by civilian casualties and culture clashes.Restrepo, a film on this topic produced and directed by Hetherington and Sebastian Junger, was nominated last year for an Academy Award for Best Documentary.

FEATURES

Long Division

During the past three decades, as Europe came together, Cyprus stayed divided. Nicholas Bray reports on Cyprus's uncertain path to unity, reminding us that the island is also a fault line—between East and West, Christianity and Islam, atavistic nationalism and borderless globalization.

Russia’s Very Secret Services

Aided by the rise of Vladimir Putin, an ex-KGB officer, Russia’s intelligence agencies have become increasingly influential. Investigative journalists Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan examine the often violent results of these agencies’ efforts to reassert Russian power in the former Soviet sphere of influence—from extra-legal renditions to assassinations.

Haiti, Violated

“I feel like God is punishing me,” says a woman who was repeatedly raped in the aftermath of last year’s earthquake in Haiti. As Clancy Nolan reveals, it’s a sentiment shared by many Haitian women as they confront an epidemic of rape in a country still reeling from the quake’s destruction—a country that also has a troubling history of tolerating sexual violence. Nolan reports on some innovative approaches to stopping the violence, and some heroic Haitians and international NGOs who have set out to help victims. Yet without progress on the larger problems of funding the reconstruction and establishing rule-of-law, it seems unlikely that even the best-intentioned efforts can solve this particularly gruesome form of aftershock.

African Land, Up For Grabs

Ashwin Parulkar reports on a 21st-century land grab in Africa. Prior to 2008, foreign investors acquired an average of 10 million acres of farmland each year. In 2009, they acquired 111 million acres, nearly 75 percent of it in sub-Saharan Africa. It’s a transfer of control unprecedented in the postcolonial era. Many claim it is leading to the displacement of tens of thousands of poor, rural villagers.

The Devil’s Curve

Last summer, a road leading to a remote Amazonian village was the site of an intense clash between Peruvian security forces and an alliance of activists and indigenous people opposed to the government’s plan to open the rainforest to oil exploration and mining. Thirty-four people died in the violence. As Emily Schmall explains, the showdown may prove to be a prelude to a regional conflict pitting the need for economic growth against environmental preservation and the rights of indigenous peoples.

Coda: Europe’s Last Word

The nations of Europe “have become less sure of precisely what they represent anymore, to themselves and to the world,” writes David A. Andelman, Editor of World Policy Journal, in his column. Nowhere is this clearer than in France, an increasingly divided country where, Andelman reports, one no longer hears the dynamic social and political dialogue that defined French political culture in earlier eras.