Guidelines

Eleventh Annual Poetry Contest: Now open.

Elixir Press is sponsoring a poetry contest open to all poets writing in English. There will be a Judge's Prize of $2,000 and an Editors' Prize of $1,000. Both winning manuscripts will be published by Elixir Press. All entries will be considered for publication. An outside judge, to be announced later, will make the final decision for the first prize. The editors will make the final decision for the second prize.

Submit by mail or submit via online submission manager.

- Manuscripts should be typed on one side of the page and on standard paper. No dot matrix unless letter quality. No more than one poem per page.

- Send a business size SASE for reply only; manuscripts cannot be returned. An SAS postcard for receipt of manuscript is optional. Electronic submissions are acknowledged by an automated e-mail, but some submitters find this e-mail is caught by their spam/bulk filters. You may check the status of your own submission through the online submission manager. Replies to electronic submissions will be made by e-mail.

- Please use a 12 to 14 point font.

- Do not send the only copy of your manuscript.

- Do not send biographical material, photographs, CDs, videos, or illustrations.

- Enclose a cover sheet stating the name of the manuscript and the author's name,address, and telephone number and a cover sheet with the title alone.

- Manuscripts must be paginated and include a table of contents and and acknowledgments page if appropriate.

- Simultaneous submissions are welcome, so long as Elixir is notified immediately if a manuscript is accepted elsewhere.

- Manuscripts must be at least 48 pages in length.

- Please secure your manuscript with either a binder clip or file folder. Do not otherwise bind your manuscript.

The entry fee is $25.

Manuscripts will be accepted from August 1 to October 31, 2010.

Submit to:

Elixir Press

P. O. Box 27029

Denver, CO 80227

***ONLINE SUBMISSION MANAGER NOW OPEN***

If you have questions, please contact us at info@elixirpress.com.

The Black River Chapbook Competition

Contest

All submissions will be considered for best-of-genre $100 cash prizes in fiction, nonfiction and poetry. Visual art, too! There is no submission fee to be considered for publication or the contest. Please check out our “Submit” page for more details.

Submit

Inscape is currently accepting submissions for the 2011 issue. The deadline is Wednesday, October 27, 2010.

You may submit one fiction piece, one nonfiction piece and up to five poems (prose poems are welcome). Prose shorter than 3,500 words is preferred, but longer pieces of exceptional quality may be considered. Previously published work will not be considered. If the selected writing has been submitted to other publications, please let us know.

Formatting requirements: typed, 12-point Times New Roman font. Include a cover sheet with name, title of work(s), genre, wordcount, email address, phone number and mailing address.

DO NOT include your name on the pages of the manuscript itself.

Submit via email with separate attachments for cover sheet and written work to inscapesubmission@gmail.com, with the applicable genre noted in the subject field (i.e. “FICTION”). If submitting more than one poem, please submit each poem in a separate file attachment (unless the poems are a series to be considered as a single unit). Please simply provide your poem’s title at the top of its page and then give us the poem–no quirky fonts or other visual layers (i.e. pencil sketches of coyotes) beyond line breaks and spacing.

Electronic submission is highly preferred, but manuscripts may be delivered here: INSCAPE 2011, Washburn University, English Department, Morgan Hall Room 258, Topeka, KS, 66621.

A special note for members of the Washburn and Topeka communities: Please note that inscape editors began utilizing a “blind” or anonymous reading process. They will carefully read your submission… But they won’t know who wrote it.

Deadline for inscape 2011: Wednesday, October 27, 2010. Regarding material selected for inclusion in the journal, inscape reserves first right of publication and indefinite use of the material online. Questions or concerns may be sent to inscapeeic@gmail.com.

Socrates – a man for our times

He was condemned to death for telling the ancient Greeks things they didn't want to hear, but his views on consumerism and trial by media are just as relevant today

By Bettany Hughes

The Death of Socrates, 1787, by Jacques Louis David. Photograph: World History Archive/AlamyTwo thousand four hundred years ago, one man tried to discover the meaning of life. His search was so radical, charismatic and counterintuitive that he become famous throughout the Mediterranean. Men – particularly young men – flocked to hear him speak. Some were inspired to imitate his ascetic habits. They wore their hair long, their feet bare, their cloaks torn. He charmed a city; soldiers, prostitutes, merchants, aristocrats – all would come to listen. As Cicero eloquently put it, "He brought philosophy down from the skies."

For close on half a century this man was allowed to philosophise unhindered on the streets of his hometown. But then things started to turn ugly. His glittering city-state suffered horribly in foreign and civil wars. The economy crashed; year in, year out, men came home dead; the population starved; the political landscape was turned upside down. And suddenly the philosopher's bright ideas, his eternal questions, his eccentric ways, started to jar. And so, on a spring morning in 399BC, the first democratic court in the story of mankind summoned the 70-year-old philosopher to the dock on two charges: disrespecting the city's traditional gods and corrupting the young. The accused was found guilty. His punishment: state-sponsored suicide, courtesy of a measure of hemlock poison in his prison cell.

The man was Socrates, the philosopher from ancient Athens and arguably the true father of western thought. Not bad, given his humble origins. The son of a stonemason, born around 469BC, Socrates was famously odd. In a city that made a cult of physical beauty (an exquisite face was thought to reveal an inner nobility of spirit) the philosopher was disturbingly ugly. Socrates had a pot-belly, a weird walk, swivelling eyes and hairy hands. As he grew up in a suburb of Athens, the city seethed with creativity – he witnessed the Greek miracle at first-hand. But when poverty-striken Socrates (he taught in the streets for free) strode through the city's central marketplace, he would harrumph provocatively, "How many things I don't need!"

Whereas all religion was public in Athens, Socrates seemed to enjoy a peculiar kind of private piety, relying on what he called his "daimonion", his "inner voice". This "demon" would come to him during strange episodes when the philosopher stood still, staring for hours. We think now he probably suffered from catalepsy, a nervous condition that causes muscular rigidity.

Putting aside his unshakable position in the global roll-call of civilisation's great and good, why should we care about this curious, clever, condemned Greek? Quite simply because Socrates's problems were our own. He lived in a city-state that was for the first time working out what role true democracy should play in human society. His hometown – successful, cash-rich – was in danger of being swamped by its own vigorous quest for beautiful objects, new experiences, foreign coins.

The philosopher also lived through (and fought in) debilitating wars, declared under the banner of demos-kratia – people power, democracy. The Peloponnesian conflict of the fifth century against Sparta and her allies was criticised by many contemporaries as being "without just cause". Although some in the region willingly took up this new idea of democratic politics, others were forced by Athens to love it at the point of a sword. Socrates questioned such blind obedience to an ideology. "What is the point," he asked, "of walls and warships and glittering statues if the men who build them are not happy?" What is the reason for living life, other than to love it?

For Socrates, the pursuit of knowledge was as essential as the air we breathe. Rather than a brainiac grey-beard, we should think of him as his contemporaries knew him: a bustling, energetic, wine-swilling, man-loving, vigorous, pug-nosed, sword-bearing war-veteran: a citizen of the world, a man of the streets.

According to his biographers Plato and Xenophon, Socrates did not just search for the meaning of life, but the meaning of our own lives. He asked fundamental questions of human existence. What makes us happy? What makes us good? What is virtue? What is love? What is fear? How should we best live our lives? Socrates saw the problems of the modern world coming; and he would certainly have something to say about how we live today.

He was anxious about the emerging power of the written word over face-to-face contact. The Athenian agora was his teaching room. Here he would jump on unsuspecting passersby, as Xenophon records. "One day Socrates met a young man on the streets of Athens. 'Where can bread be found?' asked the philosopher. The young man responded politely. 'And where can wine be found?' asked Socrates. With the same pleasant manner, the young man told Socrates where to get wine. 'And where can the good and the noble be found?' then asked Socrates. The young man was puzzled and unable to answer. 'Follow me to the streets and learn,' said the philosopher."

Whereas immediate, personal contact helped foster a kind of honesty, Socrates argued that strings of words could be manipulated, particularly when disseminated to a mass market. "You might think words spoke as if they had intelligence, but if you question them they always say only one thing . . . every word . . . when ill-treated or unjustly reviled always needs its father to protect it," he said.

When psychologists today talk of the danger for the next generation of too much keyboard and texting time, Socrates would have flashed one of his infuriating "I told you so" smiles. Our modern passion for fact-collection and box-ticking rather than a deep comprehension of the world around us would have horrified him too. What was the point, he said, of cataloguing the world without loving it? He went further: "Love is the one thing I understand."

The televised election debates earlier this year would also have given pause. Socrates was withering when it came to a polished rhetorical performance. For him a powerful, substanceless argument was a disgusting thing: rhetoric without truth was one of the greatest threats to the "good" society.

Interestingly, the TV debate experiment would have seemed old hat. Public debate and political competition (agon was the Greek word, which gives us our "agony") were the norm in democratic Athens. Every male citizen over the age of 18 was a politician. Each could present himself in the open-air assembly up on the Pnyx to raise issues for discussion or to vote. Through a complicated system of lots, ordinary men might be made the equivalent of heads of state for a year; home secretary or foreign minister for the space of a day. Those who preferred a private to a public life were labelled idiotes (hence our word idiot).

Socrates died when <a href="http://www.ahistoryofgreece.com/goldenage.htm" title="Golden Age <00ad>Athens ">Golden Age Athens – an ambitious, radical, visionary city-state – had triumphed as a leader of the world, and then over-reached herself and begun to crumble. His unusual personal piety, his guru-like attraction to the young men of the city, suddenly seemed to have a sinister tinge. And although Athens adored the notion of freedom of speech (the city even named one of its warships Parrhesia after the concept), the population had yet to resolve how far freedom of expression ratified a freedom to offend.

Socrates was, I think, a scapegoat for Athens's disappointment. When the city was feeling strong, the quirky philosopher could be tolerated. But, overrun by its enemies, starving, and with the ideology of democracy itself in question, the Athenians took a more fundamentalist view. A confident society can ask questions of itself; when it is fragile, it fears them. Socrates's famous aphorism "the unexamined life is not worth living" was, by the time of his trial, clearly beginning to jar.

After his death, Socrates's ideas had a prodigious impact on both western and eastern civilisation. His influence in Islamic culture is often overlooked – in the Middle East and North Africa, from the 11th century onwards, his ideas were said to refresh and nourish, "like . . . the purest water in the midday heat". Socrates was nominated one of the Seven Pillars of Wisdom, his nickname "The Source". So it seems a shame that, for many, Socrates has become a remote, lofty kind of a figure.

When Socrates finally stood up to face his charges in front of his fellow citizens in a religious court in the Athenian agora, he articulated one of the great pities of human society. "It is not my crimes that will convict me," he said. "But instead, rumour, gossip; the fact that by whispering together you will persuade yourselves that I am guilty." As another Greek author, Hesiod, put it, "Keep away from the gossip of people. For rumour [the Greek pheme, via fama in Latin, gives us our word fame] is an evil thing; by nature she's a light weight to lift up, yes, but heavy to carry and hard to put down again. Rumour never disappears entirely once people have indulged her."

Trial by media, by pheme, has always had a horrible potency. It was a slide in public opinion and the uncertainty of a traumatised age that brought Socrates to the hemlock. Rather than follow the example of his accusers, we should perhaps honour Socrates's exhortation to "know ourselves", to be individually honest, to do what we, not the next man, knows to be right. Not to hide behind the hatred of a herd, the roar of the crowd, but to aim, hard as it might be, towards the "good" life.

The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life, by Bettany Hughes, is published by Jonathan Cape (rrp £25). To order a copy for £21.99, including free UK mainland p&p, go to guardian.co.uk/bookshop or call 0330 333 68467

Conversations with Myself by Nelson Mandela – review

Nelson Mandela's raw memoir presents the most personal picture yet South Africa's former president, says Peter Godwin

- The Observer, Sunday 17 October 2010

Nelson Mandela's memoir blends the personal with the political. Photograph: Schalk Van Zuydam/AFP/Getty ImagesNelson Mandela disappeared, aged 44, into prison. For the next quarter of a century he became a mystery man, the missing leader. And when he finally emerged victorious in 1990, there was a pent-up demand to hear from him. Since then, books about and by Mandela have become an industry, practically a literary genre of their own: dozens of biographies, authorised and unauthorised, children's books, books distilling his leadership style, business books and art books have appeared. Is there really room for another book on the bulging Mandela shelf? What more is there to say? Quite a lot, it turns out.

Conversations with Myself isn't so much a book as a literary album, containing snippets of Mandela's life, shards from diaries, calendars, letters, and also transcripts from 50 hours of recordings by Richard Stengel, who ghosted Mandela's autobiography Long Walk to Freedom (and is now editor of Time magazine). It also contains passages from an autobiography Mandela had been working on himself, in moments snatched here and there, but has finally abandoned, and allowed to be folded into this volume.

If that all sounds somewhat scattershot and untidy, oddly it's not. The book is intensely moving, raw and unmediated, told in real time with all the changes in perspective that brings, over the years, mixing the prosaic with the momentous. Health concerns, dreams, political initiatives spill out together, to provide the fullest picture yet of Mandela.

Verne Harris, director of the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue, who led the project to select and assemble these archives, reminds us in a foreword that Mandela has become part of the creation myth of the new South Africa. As such, his public utterances were never entirely his own: even Long Walk to Freedom, his autobiography, was overseen by ANC colleagues, who realised how important the text would be to the movement. In Conversations with Myself, there are some wonderful transcripts of the ANC's Ahmed Kathrada reading the draft of Long Walk to Freedom to Mandela. Kathrada quotes several insertions from the book's publisher, pleading for more personal reaction at various seminal moments. In the transcript, a stony Mandela rarely expands further on his emotional state. He is mostly reluctant to answer the question: "How did it feel?"

It is precisely this reticence that makes Conversations with Myself such a necessary book. By going to his most personal of jottings, we finally get a glimpse of the man behind the mask. Luckily, it turns out that Mandela has always been something of a hoarder, as well as a copious note-maker, though many of his notes were seized by the police over the years, so there are inevitable holes.

The prison years, as one might expect, are particularly moving. "Until I was jailed I never fully appreciated the capacity of memory," says Mandela. Some of the abstracts are taken from his letters to his family and friends, many of which never reached their intended recipients, because they were blocked by the censors. Mandela made copies of some of these letters in a hardback notebook (it was stolen by the authorities but returned in 2004 by a penitent ex-security policeman). The notes reproduced here show Mandela's impeccably neat writing, with prison numbering and stamps on the top right-hand corner.

The book is a useful corrective to our tendency to see history through retrospectacles, to think that what happened was somehow inevitable. To the prisoners on Robben Island at the time, the overthrow of the once mighty apartheid state was a distant dream, yet still one worth fighting for. In these vivid pages one is reminded, for example, that prisoner 466/64 could have been freed decades earlier, if only he had agreed to be released into one of the black "homelands" that his jailers had created, and to renounce the armed struggle against apartheid. But he would not do so. And in an application to the University of South Africa in 1987, for an exemption from a Latin paper in his law degree, Mandela points out dispassionately that he is unlikely ever to actually practice, "as I am serving a sentence of life imprisonment".

What emerges here is a man devoid of self-pity, who is immune to the temptations of self-aggrandisement. At one point, he insists scrupulously to ghostwriter Richard Stengel that he consistently missed his target while undergoing military training.

One is reminded, too, of how steeped in history and the classics Mandela is. He read catholically, quoted liberally from War and Peace, and when preparing to launch "the struggle" consulted texts as diverse as Machiavelli, Clausewitz, Mao Zedong, and Menachem Begin. He studied the Anglo-Boer war in detail, and was later to use the Afrikaner arguments against his own jailers. But the Mandela we see here can also be abrasively self-critical. In a letter to Winnie, his wife, he quotes from As You Like It, "Sweet are the uses of adversity ... ", then says he has been looking over some of his earlier speeches and is "appalled by their pedantry, artificiality and lack of originality. The urge to impress and advertise is clearly noticeable."

The book is a valuable lens onto how Mandela made historic decisions – what he felt about communism, his Christian beliefs, the armed struggle, and the inevitable backlash by the authorities against the innocent bystanders, as well as the perpetrators. It is telling that, as a role model, he preferred Nehru to Gandhi. He also makes it clear that he only believed in non-violence as a tactic and not as a principle, though he could not say that at his trial. He discusses how he fully expected to be sentenced to death, what it's like when you think a judge "is going to turn to you and tell you now, that 'This is the end of your life'."

Painful personal issues are dealt with here too – for example, the allegation that he had once assaulted his first wife, Evelyn, "grabbing her by the throat". (Mandela's own version is that, during an argument, Evelyn pulled a red hot poker from the stove and lunged with it at his face, and he twisted it from her hand.) In 1968, when his 76-year-old mother had made her way down from the rural Transkei on her own, to visit him on Robben Island, Mandela writes: "At the end of the visit I was able to watch her as she walked slowly towards the boat which would take her back to the mainland, and somehow the thought flashed across my mind that I had seen her for the last time."

He was right: she died several months later, and he was not allowed to attend her funeral, even under escort. Ten months later his eldest son, Thembi, was killed in a car accident. Mandela's letter of 13 July 1969 to the commanding officer of Robben Island prison, asking to be present at his son's graveside, makes heartbreaking reading. It was refused.

Conversations doesn't shrink from the highly personal (Mandela made no attempt to control the book) and the strains of family life show up early. When Winnie arrives on a visit, she brings him "some silk pyjamas and nightgown… " Mandela returns them, saying, "this outfit is not for this place." The back and forth between Stengel and Mandela on the question of sex while he is in prison, and what Winnie would do without him for all those years, shows Mandela's enormous self-discipline. "She has a life outside, she meets other men…" Stengel probes. But Mandela expresses no jealousy. And when Winnie is herself jailed, Mandela sends her advice on how to cope, suggesting that she meditate for 15 minutes before bed. But Winnie is an entirely different creature from her husband. When he writes to her after a visit from their young daughters, saying how beautifully the girls were growing up, he recalls that "It was as if I had committed treason… She reminded me: 'I, not you, brought up these children whom you now prefer to me!' I was simply stunned."

There are substantive political insights here, in particular Mandela's account of the negotiations that ended apartheid. When the authorities moved him away from his comrades, isolating him in another prison, he decided to accept the move, as this would allow him to open secret talks with the apartheid authorities, without consulting his comrades. "So what I decided to do was to start negotiations without telling them, and then confront them with a fait accompli." He was taking a huge risk.

One element gleaned from the calendar section is how important the gestures made around the world were to Mandela while he was locked up. The mass petitions for his release and the attempts to make him honorary chancellor of universities, as well as the birthday cards – often dismissed as silly, ineffectual gestures – were all clearly vital in keeping up his morale.

There are unexpectedly lighthearted moments too. We get Mandela the movie critic – he finds the end of Amadeus "somewhat flat", and the very juxtaposition of Nelson Mandela and "The Nerds Take Revenge" (I think he must mean Revenge of the Nerds) is startling. But not even this prepared me for the revelation that his printed "from the desk of Nelson Mandela" message pad has pictures of a grinning Garfield in the right-hand corner.

Peter Godwin is the author of The Fear: The Last Days of Robert Mugabe (Picador).

Kinshasa Symphony:

A documentary

Kinshasa the capital of Democratic Republic of Congo is no ordinary city and at first seems an unlikely place to have an orchestra of two hundred musicians playing to Beethoven Ninth –Freude schöner Götterfunken. “Orchestre Symphonique Kimbanguiste” is the only symphony orchestra in the Congo has been in existence for 15 yrs. Riddled often with power strikes, even on performance nights, seems the least of the worries of this symphony. Kinshasa Symphony directed by Martin Baer, Claus Wischmann is a study of people in one of the world’s most chaotic cities doing their best to maintain one of the most complex systems of joint human endeavour: a symphony. The film is about the Congo, the people in Kinshasa and the power of music.

The film closely follows a few of the band members and gives a view of their personal lives, how they make a living and struggle to make it to almost daily practices. We get to see the symphony overcome odds as they prepare for an open concert with thousands attending.

The DRC does not stop with these classical musicians all self taught amateurs or trained by other musicians unfamiliar in classical training with instruments like the cello, cello bass or violin. Kinshasa continues to stand out with its remarkable musicians forming this indie breed of rudimentary collectives that play with scrap yard instruments yet seem to stand on stages from Brooklyn to Paris. Other bands I should make note of are : Konono Nº1 who collaborated with Bjork on the song earth intruders and more recently with Herbie Hancock and Baloji. Also take note of Kasai All Stars.

Kinshasa Symphony has made its rounds in the theatre circuit and is available on DVD. Its playing as part of the featured screenings next week, in New York’s College music festival CMJ.

New report shows

shocking racial inequality

in Britain

Black people five times more likely to be imprisoned, while black graduates face 24 per cent less pay.

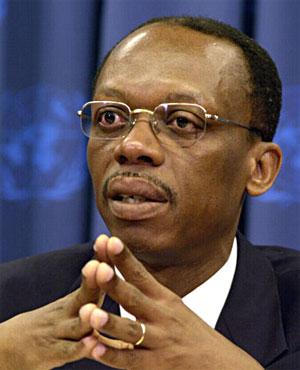

Trevor Phillips, head of the Equality and Human Rights Commission. Photograph: Getty Images

Today saw the release of How Fair is Britain, a landmark report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

The commission's first triennial report into the subject, it paints a picture of entrenched racial and social inequality.

The Guardian today picks up on the data on prisons. The proportion of black people in prison in England and Wales is now higher than in the United States. Nearly seven times more people of Afro-Caribbean and African descent are imprisoned than their share of the population, compared with about four times in the US. On average, five times more black people than white are imprisoned in England and Wales.

It's a shocking disparity, albeit hardly surprising. Despite claims that institutional racism in the police force has been tackled since the Stephen Lawrence case, the report notes that while black people make up less than 3 per cent of the population, they accounted for 15 per cent of people stopped by police.

Clearly, not enough is being done to tackle racism in the prison and justice system. But another striking aspect of the report is how this racial inequality runs through society at every level. Black children are three times as likely to be permanently excluded from school. One of the most striking comparisons in the report shows that being black and male has a greater negative impact on levels of numeracy than having a learning disability.

Even for those who make it to university, the disparity still exists. Less than ten per cent of black students are at the top Russell Group universities, compared with a quarter of white students. Around a third of black students get a first or upper-second class degree, compared with two-thirds of white students. The study also suggests that black students face a 24 per cent less pay than their white counterparts.

It is a drastic understatement to say that something here is not right. Commentators are frequently quick to attribute racially based underachievement to the disaffection and alienation of boys in the black community. There is no doubt that this has a part to play, but when these statistics - prisons, schools, universities, graduate employment - are placed alongside each other, it is not difficult to see where this disaffection comes from.

There might be a "poverty of aspiration" among black, but it is easy to understand why when the reward for a degree could be lower pay. The report raises some uncomfortable questions about the scale and nature of institutionalised racism in this country. Clearly, at every level, more must be done.

19 comments from readers

- 9xzulug

11 October 2010 at 12:04as i have a personal view point relating to how black people are perceived in the uk.many black people myself included feel we are treated in some degree as 3rd class citizens.the media since the late 60's early 70's as painted us in such a negative way which as stuck.i recall in those dark days as drug dealers,yardie gangsters,pimps,womenisers.aspirations of many blacks seems to only come through as either sportsman,musicians,yet we have taken the british way of life more than any other ethnic group to make uk our home.we have more mixed race children through our relationships with white community,we have more police,prison officers,mp's,the arm forces,fire service,nhs,the list is endless but still we feel ignored.when our offspring see the unfairness their parents receive what do we as a nation expect.INSTITIONLISED RACISM FLOURISHES SILENTLY.it's one of the main reasons black people are so angry.what black people are speaking about today is all the hatred at present is aimed at muslims.DON'T BLAME THE MESSENGER(me),BLAME THE SYSTEM WHICH HAS A GLASS CEILING which needs to be broken for ALL people to reach their potential.our nation has more ethnics than any other european nation luckily we have not allowed a right wing racist party to hijack our mainstream politics namely bnp to enter parliament otherwise watch the effect if it happens.black people will not keep turning a blind eye to the unfairness bestowed our proud,loyal,happy go lucky race.caribbeans don't have built up communities as do the asians/east europeans in many major cities,we just fit in and smile in the face of adversity but yet still we feel we are getting pushed down the pecking order in uk.THATS HOW I SEE THINGS LIVING THROUGH MY EYES IN great britain.PEACE N UNITY LEADS TO HARMONY FOR ALL WHO RESIDES ON THIS SMALL ISLAND

- Tommo

11 October 2010 at 12:08Perhaps black people should commit less crimes? Perhaps New Labour shouldn't have imported criminals from Somalia and other third world hell holes in the hopes of boosting their vote? The only real racial discrimination in Britain is against the ethnic English people and the working-class in particular. If foreign communists like Samira Shackle and Trevor Philips don't like the country, they can always go back to where their ancestors came from. They won't be missed.

- moronamid

11 October 2010 at 12:159xzulug thats what is wrong with you and your kind... you completely ignore the truth and work a lie... if blacks are so wonderful how come Africa as whole continent is such a hell hole... and how come they treated me so badly I have learned to dislike them.

So i am a racist because I despise Satan.

- Benedict

11 October 2010 at 12:17Tommo, Foreign people can't vote in General Elections so there would be no advantage in any political party 'importing' them, even if it were true.

- John Standing

11 October 2010 at 12:32Let’s try and understand this properly for once, without the blinding filter of “evil white racism”.

It is entirely likely that the rapid insertion of an African-descended population into an organic, mono-ethnic society, which post-war Britain was but America never has been, will be reflected in a higher incarceration rate for African-descended criminals. To present this reflection as "evil white racism", however, is already to loose its character.

The unique levels of criminality, especially violent and sexual criminality, which characterise African populations in Africa and in diaspore are of the Modern African mind. They are one with the competitive male assertiveness, emotional impulsiveness and general intelligence of the race. They do not change. The notion that an organic, kinship-based European society, suddenly confronted with this phenomenon, would NOT identify it and desire to control it is nonsensical. It has to be controlled. To shy away from it is to abdicate responsibility for one's own natural communal life. To pretend that it is the fault of "evil white people" is to be a-historical and, probably, intentionally blind.

Historically, the most humane control method for African populations in diaspore was powerful religious instruction. The most effective was racial segregation. Certainly in the latter case, the value at work was this the desire, which I have already mentioned, of Europeans to preserve a normal and natural life. This desire is not "white racism". It is a human right, and it should never be given up.

In Britain, it would appear, a high rate of incarceration has developed as an impromptu control method. Essentially, the natives are saying, "We don't want this." It is certainly unjust at the level of individual criminals who are too harshly treated. But to shout "racist" at the response generally is also to be racist towards a people who should not be asked to carry the burden of African criminality on its back. Its position, too, needs to be sympathetically understood - and racial blame is not a means to that end.

Whether the left, which has grown lazy in its guilt-trip, can comprehend this sadness for both races and withhold itself from the usual finger-pointing at one of them is another matter, of course.

- William

11 October 2010 at 13:26I don't understand why this research is a reason to victimize them, as opposed to just saying we need to work to help people who are part of these negative statistics. And... Now this is the revolutionary bit (MP's are you listening?). ACTUALLY DO SOMETHING ABOUT IT!!!

- Brit Born African

11 October 2010 at 13:53I must say I am disappointed at the really negative and frankly speaking, hatred filled undertones of the comments posted.

It seems some of us would rather each continent and country stuck to its own.

It's worth remembering that the Africans didn't just turn up. They were actually, brought here mostly against their will.

The consequences, right or wrong, are what we have today and we all best deal with it in the fairest way possible.

- moronamid

11 October 2010 at 13:57I was reading an article the other day...it was about a researcher in Africa researching into African language in comparison to English...well this African women said to the researcher "if you can speak English what do you need a dictionary for...I can speak all the words of my language... says it all really.

The word he was working on and could not find an equivalent for was the English word... promise. ??? the nearest he could get was a word that meant,hands tied to feet... !!!

- John Standing

11 October 2010 at 14:08BBA,

Can you explain which comments are "hatred-filled" and which are merely fact? Or are some facts hatred-filled too?

Also, would you please log the names of all the Africans living in Britain who were brought here against their will?

- swatantra nandanwar

11 October 2010 at 14:18Looks like things haven't moved on much in the last 20 years. We're still at base one, a stand still, a dynamic equilibrium, 2 steps forward and 2 steps back. I suppose that is progress, of sorts. We recognise that there is a problem, but nowhere near a solution.

But its the same with womens equality,and I dare say it'll be the same with disability.

- Brad

11 October 2010 at 14:21I'm white and have known for years how brilliant asians perform in the classroom. Saying there isn't equality just because some can't keep up is crazy. We aren't all equal so stop making us out to be!

- Lou

11 October 2010 at 14:47In the 1920s there were at least 50,000 people from ethnic minorities living in Britain.

Africans were living here in the 1700s, they were highly prevalent in the medical field here in the late 1800s. The weren't segregated, they moved in wide social circles and held on the whole more professional jobs than they did manual ones.

Any talk of Britain being a mono ethnic society is rubbish. As for rapid insertion post WW2 of an African descended population is greatly exaggerated. Mass immigration was encouraged by the government and British citizenship was granted to all members of commonwealth countries who came here and the people coming here saw themselves as coming home, to their Mother country.

Less than 500 people were aboard Windrush in 1948, hardly a rapid insertion amongst a populus at the time of 49 million.

It's very easy to see some comments as 'white racism' especially when mentioning mass influx of immigrants one fails to mention 300,000 Polish people who settled here in the same period of time referred to.

- John Standing

11 October 2010 at 15:08Brad,

Three points require to be made in reply to your comment.

First, the northern Indian average IQ is 81 - same for Pakistan - they are the same broad population group. The Moslem Pakistani performance in British schools is nearer the sub-continental mean than the Indian because the former population were less filtered by the migration process than the latter.

It is the filter which determines the differential, and the filter which explains the higher quality of the Indian population here.

2. The East Asian mean is 100 to 102, which is little different to the European. But again the better part of the demographic makes the journey west.

The difference can average more than a standard deviation of IQ points, so more than 15 points. But you need to bear in mind that the East Asian distribution is very narrow, producing a high, narrow bell curve - a small low-IQ sector but also a small sector of creative genius.

Education, let it be said, is highly valued in both Indian and East Asian homes in this country. But over time, without selection pressure to the contrary, there will occur a regression to the mean. It is possible, though, that this will be slowed by appropriate spousal selection in the countries of origin.

3. In contrast, the white working-class, in particular, but all English schoolchildren to a degree have been subject for the last quarter of a century to a debilitating programme of social and educational engineering. Basically, it constitutes a race-attack against white-skin by liberal white men and women. It is a crime against humanity, in my view.

On top of this, our children have suffered culture shock in many areas of our towns and cities, as the endless sea of foreign faces and the endless demands to celebrate Eid and Roshannah encroach. In my father's day (the 1930s) a good education at a rural school was far more rigorous and, of course, ethno-centric than today. That is what British children deserve, and that is what they are systematically denied.

- John Standing

11 October 2010 at 15:12Lou,

There is no historical grounding for race-replacement immigration.

Britain WAS a mono-ethnic country until 23rd June 1948. It will be again. You will be asked to leave.

- Lou

11 October 2010 at 15:22John Standing

Your talk of the most humane method of control for a migrating African people is seriously offensive.

Humane control? Why the need for any control and shouldn't humane actions be applied to all?

What right have the natives to control, humanely or otherwise, anyone? You talk of the natives almost allowing incarceration as a method of control like it's fact. It's not, it's you trying to justify the inherent racism that prevails in our society on a number of levels.

Your talk of the European - ergo white one presumes - desire to preserve a natural and normal life in the context of your humane control point just highlights the inherent racist undercurrent to your whole text.

- Lou

11 October 2010 at 15:24Why will I be asked to leave?

You make assumptions on my ethnicity?

Race replacementimmigration? Sums the whole racist point to your argument up.

- John Standing

11 October 2010 at 15:37There is no racism in defending one's people from replacement. The racism in the country lies solely with you and your presumption that you have a write to replace us, unbidden ... and with the political class that supports you in that against us.

- Lou

11 October 2010 at 15:40Britain has never been a mono ethnic country, ethnicity pertains to more than colour so if you want to refer to Britain's white ethnicity then kindly make that distinction.

- Beast Of No Nation

11 October 2010 at 16:049xzulug 11/10/10 12:04 wrote:"black people will not keep turning a blind eye to the unfairness bestowed our proud,loyal,happy go lucky race.caribbeans don't have built up communities as do the asians/east europeans in many major cities,we just fit in and smile in the face of adversity but yet still we feel we are getting pushed down the pecking order in uk".

Amazing, 9xzulug, you identified the problem and its cause so will you do something about it or remain in a "happy-go-lucky" state of mind? Just keep smiling, eh. My advice to you is show some teeth but not the way you do it. Will you ever fight, not in the literal sense, your corner? Do you expect others to put things on your plate that you like? Just so you know, we live in a Capitalist Democracy where reward matches contribution and you have to work hard to succeed. Being laid back, carefree and oblivious of your surroundings is not a recipe for success.

You are right when you say Muslim's are the new Black's. Since 7/7/05 attention turned to Muslim's and our society have bent over backwards to show Black's in a positive light; there are several Black TV presenters and Newsreaders/Reporters on TV, there are Black men/women in most TV adverts/soaps, no more racist chants at football matches, a Black woman was one of the candidates in the last Labour leadership election...the list goes on and on. So we have many Black role models; something that in the past was always identified as being the reason for Black youth underachievement. You no longer have to run the gauntlet of abuse, you should be more confident and ambitious than the Black youths of the 70's, 80's and 90's. No excuses.

Caribbean's/Blacks do not "have built up communities"? They do, Brixton, Hackney, Peckham, Haringey.

CARMEN SOUZA & THEO PAS'CAL - SOUS LE CIEL DE PARIS

Carmen Souza - Voice, Guitar

Theo Pas'cal - Acoustic BassBy Édith Piaf

Sous le ciel de Paris

S'envole une chanson

Hum Hum

Elle est née d'aujourd'hui

Dans le cœur d'un garçon

Sous le ciel de Paris

Marchent des amoureux

Hum Hum

Leur bonheur se construit

Sur un air fait pour euxUnder the sky of Paris

A song escapes

Hum hum

It was just invented today

In the heart of a young man

Under the sky of Paris

Lovers are walking

Hum hum

Their happiness being fashioned

On a melody made just for themSous le pont de Bercy

Un philosophe assis

Deux musiciens quelques badauds

Puis les gens par milliers

Sous le ciel de Paris

Jusqu'au soir vont chanter

Hum Hum

L'hymne d'un peuple épris

De sa vieille citéUnder the Bercy bridge

A philosopher sits

Two musicians, a few loafers

And then thousands of people

Under the sky of Paris

They will be singing until night falls

Hum hum

The song of a people in love

With their old city.Près de Notre Dame

Parfois couve un drame

Oui mais à Paname

Tout peut s'arranger

Quelques rayons

Du ciel d'été

L'accordéon

D'un marinier

L'espoir fleurit

Au ciel de ParisClose to Notre Dame (large church in Paris)

Sometimes a drama is smouldering

Sure, but in Paname ( a nickname for Paris)

There are no problems

A few sun rays

From the summer sky

An accordeon

Played by a sailor

Hope springs again

Under the sky of ParisSous le ciel de Paris

Coule un fleuve joyeux

Hum Hum

Il endort dans la nuit

Les clochards et les gueux

Sous le ciel de Paris

Les oiseaux du Bon Dieu

Hum Hum

Viennent du monde entier

Pour bavarder entre euxUnder the sky of Paris

Runs a happy river

Hum hum

During the night it lulls to sleep

The poor people of the street

Under the sky of Paris

God's birds

Hum hum

Come from all around the world

To have a chatEt le ciel de Paris

A son secret pour lui

Depuis vingt siècles il est épris

De notre Ile Saint Louis

Quand elle lui sourit

Il met son habit bleu

Hum Hum

Quand il pleut sur Paris

C'est qu'il est malheureux

Quand il est trop jaloux

De ses millions d'amants

Hum Hum

Il fait gronder sur nous

Son tonnerr' éclatant

Mais le ciel de Paris

N'est pas longtemps cruel

Hum Hum

Pour se fair' pardonner

Il offre un arc en cielAnd the sky of Paris

Has its own secret

For 20 centuries it has been in love

With our Saint-Louis Island (an island in the Seine river)

When the island smiles at it

The sky puts on its blue suit

Hum hum

When it rains on Paris

It means the sky is sad

Because it is jealous

Of the island's millions of lovers

Hum hum

It roars over us

Its thunderous sounds

But the sky of Paris

Is never cruel for long

To beg our forgiveness

It offers us a rainbow

Doudou N'diaye Rose-Sabar & Djabote

special post 7and the lastSmall and lean, with a keen eye, Doudou N’Diaye Rose is a living legend.He is Dakar's head drummer , composer of Senegal's national anthem,

and the father of forty-two children, all of them percussionists, who along with various sons and daughters-in-law supply the orchestra with its new members. Despite the traditional ban on female drum playing, there are in fact around twenty women drummers in Doudou Ndiaye Rose's orchestra – a great rarity in Africa.

In Senegal, he is considered a national treasure. For the past forty years, Doudou Ndiaye Rose has represented the Senegalese percussion tradition associated with the many artists he has played with....

continue reading this nice portrait of Doudou Ndiaye Rose prepared at rfi musique

this is one more of these must see videos 58:09 min.relax if you mayor you might prefer the shorter video below

Doudou Ndiaye Rose - Chef Tambour Major (France, 1986)56:09Doudou Ndiaye Rose Chef Tambour Major et ses cent batteurs Emission: Béatrice Soulé Montage : Ange-Marie Revel Son : Bruno Lejean Directrice de production : Maried-Therese Isambart Realisation : Jean-Pierre Janssen This video was realized thanks to: L'office de Radiodiffusion et Television du Senegal, Air Afrique and Nancy Jazz Pulsation With participation of: Les Rosettes Les Majorettes du Lycee Kennedy Youssou Ndour L'Orquestre National du Senegal El Adj sissoko Ousmane Douf Balde Diola and the whole family of Doudou Ndiaye Rose

this exceptional Sabar lp is a present to the blog from our valuable friend ngoniI will thank him again from here for his generous offers.and I will add the classic Djabote for you, to complete your sabar educationand yes I'm terribly sorry I almost forgot the family!

the second part is here