Dead Rock Star Interview Writing Contest!

So you’re a big-time music journalist, and as such, you have been blessed with great powers, one of which is the ability to interview dead rock stars. Maybe you’d like to ask Jimi Hendrix if there are any good recording studios in the afterlife. Or inquire as to Kurt Cobain’s latest project with Ian Curtis. Or grill Billy Joel on his choice to record an album of Sinatra covers. (Wait, Billy Joel’s not dead – though a case could be made …)

Anyhoo, Xomba has teamed up with Filter music magazine (Filtermagazine.com) to present our latest writing contest. We’d like you to pick a dead rock star and create a mock interview. Yep, set it up just like a real interview: You ask the questions and make up their answers. Ask anything you like (and answer for them. They won’t mind; they’re dead.) The interview can be serious, humorous, insightful or incendiary. The more inventive, the better.

- Entries must be at least 350 words.

- Deadline for entries is midnight on Monday, Nov. 1.

The winning entry will be featured on Filter’s homepage for a week. If you’re not already a member of Xomba, sign up here and get writing.

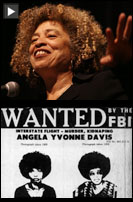

For over four decades, Angela Davis has been one of most influential activists and intellectuals in the United States. An icon of the 1970s black liberation movement, her work around issues of gender, race, class and prisons has influenced critical thought and social movements for years. She is a leading advocate for prison abolition, a position informed by her own experience as a fugitive on the FBI’s Top 10 most wanted list forty years ago. Davis rose to national attention in 1969 when she was fired as a professor from UCLA as a result of her membership in the Communist party and her leading a campaign to defend three black prisoners at Soledad prison. Today she is a university professor and the founder of the group Critical Resistance, a grassroots effort to end the prison-industrial complex. This year she edited a new edition of Frederick Douglass’ classic work, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. We spend the hour with Angela Davis and play rare archival footage of her. [includes rush transcript]

Guest:

AMY GOODMAN: Over four decades, Angela Davis has been one of most influential activists and intellectuals in the United States. An icon of the 1970s black liberation movement, her work around issues of gender, race, class and prisons has influenced critical thought and social movements across several generations. She is a leading advocate for prison abolition, a position informed by her own experience as a fugitive on the FBI’s top-ten most wanted list forty years ago.

Angela Davis rose to national attention in 1969 when she was fired as a professor from UCLA. It was Ronald Reagan who had her fired as a result of her membership in the Communist party and her leading a campaign to defend three black prisoners at Soledad prison. This is a clip from an NBC newscast in 1969 after the UCLA Board of Regents voted to fire her. It begins with then California Governor Ronald Reagan explaining why he pushed for her ouster.

GOV. RONALD REAGAN: Academic freedom does not include attacks on other faculty members or on the administration of the university or speaking to incite trouble on other campuses. Now, I think, once again, in this particular case, we’re talking simply about an issue of whether to hire or not. And this comes up a great many times, and there are many people who are decided not to hire, and it does not become a great case in which publicly there has to be a debate as to why we chose someone else instead of this other individual.

NBC NEWS: While the Regents were voting, Ms. Davis was a few blocks away in a rally, protesting the treatment of black prisoners in Soledad State Prison. She sees her dismissal as a case of political repression, which she may or may not challenge.

ANGELA DAVIS: I’m going to keep on struggling to free the Soledad Brothers and all political prisoners, because I think that what has happened to me is only a very tiny, minute example of what is happening to them. I suppose I just lost that job at UCLA as a result of my political opinions and activities.

AMY GOODMAN: In 1970, Angela Davis was charged with murder after guns used in a botched kidnapping attempt to free the prisoners were alleged to be hers. Davis briefly escaped capture before her arrest here in New York City forty years ago this month. In an interview from prison then, she talked about the role of prisons in the black liberation struggle.

ANGELA DAVIS: There came a point where the revolutionary forces at work in the black community began to express themselves in jails and prisons. However, unlike, say, the campuses, unlike any other area in the society, even the armed forces, the room for any kind of meaningful political activity is so narrow that obviously, as soon as the prison officials became aware of what was happening, they would confront these new developments with the most devastating kind of repression imaginable. And this is why, when I was involved in all of the problems at UCLA surrounding my membership in the Communist party and when I was fighting for my job, I had just become aware of what was happening in the prisons, and I always insisted that people who were supporting me in my fight to retain my job, regardless of what my political beliefs and political activities were, had to look at the prisons.

AMY GOODMAN: Angela Davis, speaking from prison forty years ago. In 1972, she was acquitted of all charges in a trial that drew international attention.

Instead of shying away from public life, Davis resumed her academic work and social activism. Today she is professor emerita of history of consciousness and feminist studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a visiting distinguished professor at Syracuse University. She is founder of the group Critical Resistance, a grassroots effort to end the prison-industrial complex.

Her books include Women, Race and Class, Abolition Democracy, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, Are Prisons Obsolete? This year she came out with a new critical edition of Frederick Douglass’s classic work Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. She will be appearing with the author Toni Morrison at the New York Public Library on October 27th for an event called "Frederick Douglass: Literacy, Libraries, and Liberation."

Professor Angela Davis joins me now for an extended conversation from Ithaca, New York.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Angela Davis.

ANGELA DAVIS: Thank you very much, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we have just taken not only listeners and viewers, but you, as well, on a journey through your life. It was quite remarkable to see then-Governor Ronald Reagan speaking about you. Why was he so intent on preventing you from taking on your assistant professorship at UCLA?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, I’ve always thought that it was not so much about me as an individual as it was about discovering a scapegoat who could be targeted in order to frighten people away from the radical movement at that time, and especially the black liberation movement. You know, one of the points that I became aware of after I was arrested was that literally hundreds, perhaps thousands, of black women were stopped and arrested. And, of course, not all of them could have looked like me. So, yeah, I think this was a part of a strategy of terror designed to prevent people from getting involved in movements at that time.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, of course, it only mobilized people. He put pressure on the California Regents. They fired you before you could even teach your first class, except you did. What did you have? Something like 150 people enrolled in the class? But 1,500 people came out as you decided to teach it anyway, even though you were fired?

ANGELA DAVIS: Yeah. Yeah, that was really a marvelous display of solidarity. I, myself, was really shocked to see so many people. And it was interesting, because that first class was in a course that I had designed to—a course by the title of "Recurring Philosophical Themes in Black Literature." I was teaching in the Philosophy Department, but we did not have at that time a field called black philosophy or African philosophy or African American philosophy. So I was improvising, attempting to address some issues that would also be relevant for the contemporary period.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to go to a break, and we’re going to come back. And we want to talk about your life, and we also want to talk about this very interesting new critical edition of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself, with essays that—written by you, Angela, as well as your lectures on liberation. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: "Angela" by John and Yoko. That’s right, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Plastic Ono Band. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. Our guest for the hour is Angela Davis.

Angela, does that song bring back memories?

ANGELA DAVIS: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely, it does, yes. I can hardly believe that forty years have gone by, four decades. And it’s interesting because on October 13th, a couple of days ago, someone said, "Isn’t this the anniversary of your arrest?" And I thought about it, and I said, "Yes." The person said, "Isn’t it the thirtieth anniversary of your arrest?" And I said, "Actually, it is. But it’s not the thirtieth, it’s the fortieth." And I had to explain that I generally remember the date of my liberation, but I try—I think I repress the date of my arrest.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let’s talk about that. So, you went from, well, first getting a job to be an assistant professor at UCLA to Ronald Reagan, then governor, having you fired, to teaching 1,500 people anyway, because they came out in solidarity, students and professors, to ending up in jail. How did you wind up in jail?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, while I was teaching at UCLA, I received threats literally every day, death threats. As a matter of fact, someone even came into the Philosophy Department looking for me. I was not there. And they attacked, physically attacked, Professor Kalish, who was the chair of Philosophy Department at that time. So it was necessary for me to have security, and during those days it was armed security. On the campus, the UCLA police accompanied me to each class, and they searched my car each day to make sure there had not been a bomb planted, and so forth. And I also had to have people who were doing security for me in my house and wherever I went. I should say the—I always like to point out that the UCLA police did a marvelous job of doing security on the campus, but they waved goodbye to me every day as I exited the campus. And I used to like to say that UCLA wanted to make sure that I wasn’t killed on the campus; they really didn’t care what happened after I left the campus.

But in any event, I purchased a number of weapons. And people who did security for me used those weapons. One of the persons was the younger brother of George Jackson, Jonathan Jackson. And on August 7th, 1970, he took those weapons and went into a courtroom in Marin County, San Rafael, California. And Jonathan was killed in the process, as were a number of prisoners. You know, Jonathan was very young and very passionately involved with his brother’s situation, George Jackson. He really wanted to see his brother free. And while he was active in the campaign to free him, as many of us were, I don’t think that Jonathan recognized that perhaps we could indeed free them through our activities, organizing activities, the building of a mass movement. In any event, as a result of the event on August 7th, I was charged with murder, kidnapping and conspiracy, because the guns that were used were registered in my name. And after that, of course, I was placed on the FBI’s ten most wanted list. I was underground for several months, until I was arrested in New York City on October 13th, 1970.

AMY GOODMAN: And you were held for more than a year in prison.

ANGELA DAVIS: I was held for sixteen months. I was released on bail before my trial took place. So the whole ordeal lasted about eighteen months. I was arrested in October of 1970, and my trial concluded with an acquittal at the beginning of June, on June 4th, 1972.

AMY GOODMAN: How did your experience in prison and going through what you went through then shape you today and your work in these forty years, in these four decades?

ANGELA DAVIS: Of course, one always creates narratives of one’s life in retrospect. And I do think that the period of time I spent behind bars helped to consolidate an interest which was already there, namely, working around cases involving political prisoners. George Jackson, of course, helped us to understand that it wassn’t just a question of freeing political prisoners, but it was a question of looking at the institution of the prison and its repressive role and its role in shoring up and reproducing a racism.

Actually, I can talk about the fact that my mother was involved in campaigns to free political prisoners. She was a very active member of the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis, but she had been involved as a college student in the campaign to free the Scottsboro 9. So, I had actually, in a sense, followed in the footsteps—

AMY GOODMAN: And the Scottsboro 9? The Scottsboro 9 were...? The young men who were accused of rape.

ANGELA DAVIS: Nine young black men who were accused of rape in Alabama and who were arrested and held in prison for many years, some charged with death. And the last Scottsboro defendant was not released until the 1980s.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve mentioned your—

ANGELA DAVIS: And so, I was saying that that—

AMY GOODMAN: Go ahead.

ANGELA DAVIS: No, I was saying that, in a sense, that work around political prisoners is, in part, an aspect of the way I grew up. It was, in a sense, in my blood already, when I began to work on cases such as the campaign to free Nelson Mandela, the campaign to free Lolita Lebrón and the Puerto Rican political prisoners, and of course the Attica Brothers and many others.

AMY GOODMAN: You were born, Angela Davis, in Birmingham, Alabama, home of Bull Connor. Interestingly, Condoleezza Rice just came out with a memoir of her time in Birmingham, her civil rights growing up, as she describes it.

ANGELA DAVIS: Yes. We were—we grew up in the same area. I didn’t know Condoleezza Rice. She lived in a different part of the city, and she’s somewhat younger than I. But it’s always interesting to see how trajectories can be so markedly different, even though one had what one might consider to be a similar upbringing.

AMY GOODMAN: Very interesting. And we can have a longer discussion about that. Maybe we’ll have you and Condoleezza Rice on.

ANGELA DAVIS: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: And it would be a very interesting time of reminiscence.

ANGELA DAVIS: I’m not sure about that, but...

AMY GOODMAN: You know, it’s interesting. Recently we had Michelle Alexander on, the author of The New Jim Crow, and she said there are more African Americans under correctional control today, in prison or jail, on probation or parole, than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began, which is an interesting way to link your work today around the issue of prisons—the US has more prisoners than anywhere in the world—back to the middle of the nineteenth century, when Frederick Douglass was enslaved, your newest book.

ANGELA DAVIS: Absolutely. And, of course, any of us who are interested in African American history, and particularly the black liberation movement, have to address Frederick Douglass, the system of slavery. And we’ve come to think about the prison-industrial complex as linked very much to slavery, as revealing the sediments and the vestiges of slavery, as providing evidence that the slavery we may have thought was abolished with the Thirteenth Amendment is still very much with us. It haunts us, especially in the form of this vast prison-industrial complex, a prison system within the US that holds something like 2.5 million people, more people in prison than anywhere else in the world, more people per capita, as well. The rate of incarceration, one in 100 adults in the US is behind bars. And that’s really only because of the disproportionate number of black people and people of color whose lives have been claimed by the prison system.

As a matter of fact, it’s very interesting that we think about the history of the prison system in this country as grounded largely in the northeastern penitentiaries, the Auburn system here in New York, not very far from where I am teaching, and the Philadelphia system. And as a matter of fact, Robert Perkinson has written an interesting new book called Texas Tough, in which he argues that the Southern system, which emerged in the aftermath of slavery, which made use of the violent forms of repression that were linked to slavery, is as much a part of the genealogy of punishment in the US as the New York and the Pennsylvania penitentiaries.

AMY GOODMAN: We, by the way—I want to let our viewers and listeners know—have a Facebook page, facebook.com/democracynow, where you can post questions for Professor Angela Davis. She’s speaking to us from Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York—and a shout-out to our friends at Ithaca College—and has written a new critical edition that features her lectures on liberation, along with the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. And I would like to go there now with you, Angela Davis, the idea of the plantation-to-prison pipeline. Let’s start from the beginning. And why now, at this point in your work, in your activism, in your life, you’ve chosen to go back to, to bring out once again and give us your critical perspective on Frederick Douglass? Why was he so significant. And tell us about his life, as you respond to that question.

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, Frederick Douglass is, of course, the germinal figure in the history of African American liberation. But Frederick Douglass is also an absolutely central figure in US history. And I think that it is important to understand his contributions, particularly given the fact that we constantly refer to him. And in my introduction, I pointed out that when Barack Obama was campaigning for office, he very frequently referred to that—perhaps the most famous passage in Frederick Douglass’s work, which was a speech that he gave on West Indian Day. And it begins, "If there is no struggle, there is no progress."

I thought that it might be important to think about Frederick Douglass from the vantage point of where we are in the twenty-first century, particularly given the feminist contributions, given the contributions of black feminism, particularly because, historically, the conceptualization of freedom has been linked to manhood, the conceptualization of black freedom to black manhood. And I refer to that passage that everyone who has read Frederick Douglass knows, about his confrontation with the slave breaker Covey. And in the aftermath of this physical altercation, in which Frederick Douglass emerges as the winner, he realizes that he has, in the process, defended his manhood. But that is his way of experiencing the possibilities of freedom. So I ask in that introduction, you know, what about women? What is the trajectory of freedom for women? And in the nineteenth century, of course, at least within the literary genre of the sentimental novel, that trajectory ended with marriage. So marriage was the equivalent form of freedom for women. And I also refer to Harriet Jacobs’ wonderful narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, in which she makes a point of pointing out that her story does not end with marriage, but rather with freedom. So the question is, how can we recognize the masculinist dimensions of our conception of freedom and move on from there here in the twenty-first century?

AMY GOODMAN: And can you talk about the significance of Frederick Douglass being enslaved as a youth, as a teenager in St. Michaels? Interestingly, Covey’s property in St. Michaels is called Mount Misery, is now owned by, well, former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. That’s his vacation home. He bought it in 2003 to be near his close friend Vice President Dick Cheney. But—

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, it’s very interesting. Go ahead.

AMY GOODMAN: I don’t know if there’s a "but" there, but if you can talk about how Frederick Douglass—what his role in the abolition movement was and how the abolition movement shaped not just Black America, shaped America?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, Frederick Douglass was the most prominent black abolitionist—the most prominent abolitionist, I would argue, because such an amazing figure as William Lloyd Garrison, the great white abolitionist, also had his problems. And then I would like to perhaps point out that we have still not come to grips with the fact that John Brown was a part of that abolitionist movement. He was during that time referred to as insane, and many people treat him today as if he must have been mentally disordered in order to devote his life in that way to the struggle for freedom for black slaves. Frederick Douglass was the germinal figure of the abolitionist movement.

And abolition—the abolitionist movement is important for us today, because it continues—well, it has its contemporary presence in what we call the twenty-first century abolitionist movement, which attempts to, first of all, of course, abolish the death penalty—and I’m thinking of Mumia Abu-Jamal, who is such an important figure in that abolitionist movement—and to abolish the prison-industrial complex. We see the effort to abolish imprisonment as the dominant mode of punishment and to shift resources from punishment to education, to housing, etc., in a way that is very similar to what Frederick Douglass might have argued with respect to the abolition of slavery. And, of course, here, we also have to mention W.E.B. DuBois, who called for—whose notion of abolition democracy is very much an inspiration for those of us who are struggling to abolish the prison-industrial complex today.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break, and then we’re going to come back. Angela Davis is our guest. Professor Davis is now teaching at Syracuse University. She is professor emerita of University of California, Santa Cruz. She is an author and activist. Her latest book is the release of a critical edition of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Oh, yes, Ma Rainey, here on Democracy Now!, certainly ties in to an earlier book of Angela Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism. Gertrude "Ma" Rainey met Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday. In fact, if we can be a little stream of consciousness here, Angela Davis, our guest for the hour, how would you tie in Ma Rainey with the resistance movement that we’re talking about today?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, I think that the blues women, blues men, but especially blues women, gave expression to a whole range of social issues from the vantage point of working-class black women. And I came to study women and the blues because I was dissatisfied with what was available in the written archives regarding the history of black women’s feminist approaches. So I made an argument in that book that many of the issues that we claim as feminist issues—violence against women, for example, the relationship between intimate violence and institutional violence—could be discovered in the lyrics of the blues, in the work of Ma Rainey and, of course, Bessie Smith and Victoria Spivey and many others.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Davis, we’ve just gotten a Facebook question. Folks going to facebook.com/democracynow. Daniel Chard writes, “In your book Abolition Democracy, you briefly discuss the US prison system as a form of state terrorism. In what ways do prisons function as a form of terrorism?”

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, prisons create the assumption that those who are a threat to our safety and security are behind bars, but in actuality, the techniques of violence, the techniques of terror that are most dangerous, are the ones used within the system itself. And I would say that it’s not simply a question of racist repression. It’s also a question of gender repression. It’s also a question of repression of sexualities. You know, one of the—as I’ve been pointing out, one of the most interesting developments within the anti-prison movement looks at the way in which the prison itself serves as a gendering apparatus, looks at the violence inflicted on people who do not identify as male or female in the conventional sense, who identify as transgender or as gender-nonconforming, the violence that is inflicted on people who do not subscribe to compulsory heterosexuality, violence against lesbians, violence against gay men, so that you might say that the prison is this institution that is grounded, in so many ways, in violence.

And the violence of slavery, which we assume was abolished with the Thirteenth Amendment and afterwards, is very much at work within US prison institutions. And because the prison has been marketed on the global capitalist circuit, we discover these prisons, the US-style prisons now, all over the world, in the Global North as well as the Global South.

AMY GOODMAN: How would you like to see them changed? You’re a founder of the Critical Resistance movement in this country. You talk about the abolition of the prison-industrial complex. What would you want to see in this country?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, I would like to see, as Fay Honey Knopp, who was an abolitionist during the '70s and the ’80s and one of the co-authors of a wonderful book called Instead of Prisons: An Abolitionist Handbook, you know, I would like to see an emphasis on decarceration, an emphasis on ex-carceration. You know, I would like to see us examine the ways in which the criminalization of certain behaviors, such as drug use and drug trafficking, has allowed the prison system to expand the way that it has. The vast majority of women who are behind bars are in prison in relation to a drug charge. I would like to see us decriminalize drug use, for example. I would like to see us engage in a national conversation on true alternatives to incarceration. I'm not speaking about house arrest and probation and parole and so forth. I’m talking about ways of addressing social problems that are entirely disconnected from law enforcement.

And that would mean an emphasis on education. As Frederick Douglass pointed out, education is indeed the way to liberation. Frederick Douglass taught himself how to read and write, because he recognized that there could be no liberation without education. Now there seems to be a greater emphasis on incarceration than education. So we have to say, "Education, not incarceration." And then, of course, healthcare, physical healthcare, mental healthcare. And, you know, even though we should be happy that some kind of healthcare bill was passed, but it doesn’t even begin to address the real problems that people have in this country. Mental healthcare, the prison system serves as a receptacle for those who are unable to find—poor people who are unable to find treatment for mental and emotional disorders. So, in a sense, you might say that the abolitionist movement, the prison abolitionist movement, is a movement for a better world, for a different society, for a world that doesn’t need to depend on prisons, because the kinds of institutions that provide—that serve people’s needs will be available.

And in this sense, we have to return to the notion of abolition democracy. There were those who were struggling to simply get rid of freedom—sorry, there those who were struggling to simply get rid of prisons and assuming that freedom would be the negation of slavery. There were those who were struggling to simply get rid of slavery, assuming that freedom would be the negation of slavery. But there were those who recognized that there could be no freedom without economic equality, without political equality, without educational institutions. And even though we are under the impression that we abolished slavery, we’re still living with those vestiges, the lack of an educational system that serves all people regardless of their economic background, the lack of a healthcare system, the lack of access to housing. And this is in large part the role that the prison has played. It has become a receptacle for those who have not been able to find a place in society. And this is true not only in the US, but literally all over the world. This is why we are experiencing an expansion of the prison system in Europe, in Asia, in Africa, in Latin America. And this is very much connected to the rise in global capitalism. So, prison abolition is about building a new world.

AMY GOODMAN: Angela Davis, I wanted to ask you about building a new world and ask you about your thoughts on the eve of the election of President Obama, what you were thinking, the hopes you had at the time, and now, two years later, where we stand today. I mean, November 4th, 2008, this remarkable moment, an African American man elected in a land with the legacy of slavery, you know, the land of Frederick Douglass. Where we came from then and where we are today, Professor Davis?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, of course, initially, few people believed that a figure like Barack Obama could ever be elected to the presidency of the United States, and because there were those who persisted, and, you know, largely young people, who helped to build this movement to elect Barack Obama, making use of all of the new technologies of communication. And so, on that day, November 4th, 2008, when Obama was elected, this was a world historical event. People celebrated literally all over the world—in Africa, in Europe, in Asia, in South America, in the Caribbean, in the US. I was in Oakland, and there was literally dancing in the street. I didn’t—I don’t remember any other moment that can compare to that collective euphoria that gripped people all over the world.

Now, here we are two years later, and many people are treating this as if it were business as usual. As a matter of fact, many people are dissatisfied with the Obama administration, because they fail to fulfill all of our dreams. And, you know, one of the points that I frequently make is that we have to beware of our tendency here in this country to look for messiahs and to project our own possible potential power on to others. What really disturbs me is that we have failed. Well, of course, I’m dissatisfied with many of the things that Obama has done. The war in Afghanistan needs to end right now. The healthcare bill could have been much stronger than it turned out to be. There are many issues about which we can be critical of Obama, but at the same time, I think we need to be critical of ourselves for not generating the kind of mass pressure to compel the Obama administration to move in a more progressive direction, remembering that the election was, in large part, primarily the result of just such a mass movement that was created by ordinary people all over the country.

AMY GOODMAN: That issue of movements versus a person, that certainly brings us back to Frederick Douglass, while such a significant person within the abolitionist movement, needing that movement to change America, and where you see movements today and also the power of money. We’re just about to come into another election day, midterm elections, with money drowning politics now, unleashed throughout the United States. Also the money and the power of the prison lobby in this country, how prisons stay not because of the logic of prisons necessarily, but because now they are big business, and the privatization of prisons. Can you talk about how movements are affected by money and the power of the corporation today, how you think movements can take on this corporate money?

ANGELA DAVIS: Well, of course, it is far more difficult than it has ever been to engage in and move successfully in the direction of progressive change, and this has to do with the fact that capitalism has really consolidated its influence on so many levels, and as you pointed out, privatization, not only privatization of prisons, but privatization of educations. I think of, you know, Looking for Superman and the move away from struggling for a public education system, which is what we need, that will satisfy the needs of all the people. So, privatization, corporatization, global capitalism, but again, I don’t think that we can assume that we are entirely powerless if we have no access to that money.

AMY GOODMAN: We have fifteen seconds.

ANGELA DAVIS: Again, I would return to the election of Barack Obama. Barack Obama was elected despite that kind of a lobby, despite the power of money. And so, we have to continue the campaign for a better world, drawing upon all of our resources.

AMY GOODMAN: Angela Davis, I want to thank you very much for being with us. We didn’t have enough time. You can go to our website at democracynow.org.

ANGELA DAVIS: Thank you very much, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Orleans from 2001-2003. A beloved teacher, friend and colleague, Jim taught all levels of creative writing at UNO from 1977 until his death from cancer in 2004. He was author of the novels Playing Favorites and Just Friends, the story collection Evening of Wonders, and, with his friend and colleague, Joanna Leake, the textbooks The Illustrated Guide to Writing and The Illustrated Guide to College Composition.

Orleans from 2001-2003. A beloved teacher, friend and colleague, Jim taught all levels of creative writing at UNO from 1977 until his death from cancer in 2004. He was author of the novels Playing Favorites and Just Friends, the story collection Evening of Wonders, and, with his friend and colleague, Joanna Leake, the textbooks The Illustrated Guide to Writing and The Illustrated Guide to College Composition.