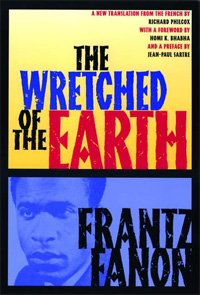

Classic book:

The Wretched of the Earth

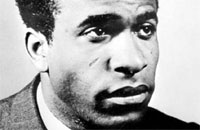

Richard Pithouse on The Wretched of the Earth, by Frantz Fanon

In 1961 Frantz Fanon dictated most of his last book, Les Damnés de la Terre, translated as The Wretched of the Earth, from a mattress on the floor of a flat in Tunis. He was 36 years old and dying of leukaemia. The disease had recently blinded him for some weeks but he managed to complete the book in ten weeks in a race against death.

Fanon, who was from Martinique in the Caribbean, had ended up Tunisia after he joined the Algerian national liberation movement in 1954. He had joined the Free French Forces fighting the Nazis as a teenager and, as a result, had been able to study medicine in France after the war. He had specialised in psychiatry and had taken a post in a psychiatric hospital in colonial Algeria.

Fanon’s first book, Black Skin, White Masks, was written when he was a student in France and published in 1952. He was 27. It remains an arrestingly original work in which a poetic form of expression and philosophical and literary erudition are woven into a profound and moving examination of the lived experience of racism. From this first book Fanon’s politics were rooted in a radical humanism, with a commitment, in his words, to ‘recognise the open door of every consciousness’. It remains a canonical text in critical race studies and a book that continues to inspire people around the world.

Fanon’s second book, A Dying Colonialism, was published in 1959. It deals with what he called the mutations in culture as people become mobilised in an anti-colonial war. Anyone who has been able to participate in a genuine mass mobilisation will immediately recognise the value and accuracy of his description of how social relations can change in struggle.

The Wretched of the Earth draws on Fanon’s involvement in the Algerian struggle against French colonialism as well as his travels around Africa as an ambassador for the Algerian national liberation movement. It begins with an account of the colonial city, ‘this world divided in two’, and goes on to examine the internalisation of colonial violence among the oppressed, the resulting violence among the oppressed, and the moment when violence is turned back on colonial oppression.

Fanon then turns his critical attention towards anti‑colonial resistance, stressing that in the colonial situation Marxism needs to be ‘stretched’ and paying particular attention to the political agency of ordinary people, including peasants and the urban poor. He is committed to forms of struggle that are genuinely mass-based and participatory.

The book’s third focus is an examination of the pathologies of the regimes that came to power in Africa after colonialism. In Fanon’s estimation they took over rather than undid colonial systems, demobilised the mass movements that had brought them to power and used their own political credibility to entrench authoritarian and predatory regimes. Against this, still committed to a radical humanism, he posed a refusal of technocratic approaches to development and the full involvement of the people in both political and economic life. The final chapter of the book, drawing on Fanon’s case notes from his period as a psychiatrist in Algeria, investigates the damage done to human beings by colonialism and violence.

The Wretched of the Earth was banned on publication in France and copies were seized from bookshops. But it was heralded in radical black circles in the US and taken up in places such as Iran and Sri Lanka. Fifty years later it remains the key text in radical circles in South Africa, where it is regularly cited by grass-roots militants.

Initial readings of the book often caricatured Fanon’s endorsement of violence against colonial regimes. Fanon’s support for violent struggle was often read outside the context of the extraordinary violence of French colonialism in Algeria and there has been a racist double standard in which Fanon is excoriated for endorsing violent struggle while white intellectuals, such as, say, Jean-Paul Sartre or George Orwell, are not subject to the same condemnation. Although he had been decorated for bravery while serving in the Free French Forces, Fanon had a personal horror of violence and was acutely aware of the damage that it can do to individuals and societies.

Many of the misreadings of The Wretched of the Earth are due to the way the book is developed as an unfolding narrative in which consciousness changes in the vortex of struggle. Statements affirmed with unqualified emphasis at one point are often questioned later on. This means that the book has to be read as a whole to be properly understood and that simply taking isolated quotes or extracts will not give an accurate impression of the author’s intentions.

Fanon left this world as The Wretched of the Earth entered it. Fifty years on, his final book retains an extraordinary political charge in countries where it remains necessary to oppose both new forms of colonial or neo-colonial power and new forms of elite accommodation with that power in the name of the nation.