by Minister of Information JR Valrey

Michelle Alexander speaks to the prisoners at Washington State Reformatory’s University Beyond Bars.

Professor Michelle Alexander’s new book “The New Jim Crow” is a monumental, well researched piece of work that presents documented facts in down to earth English about the mass incarceration of Black people within the United States’ national concentration camp system. At one point in “The New Jim Crow,” Professor Alexander presents evidence that more Black people are enslaved behind bars today than were enslaved on the plantations in 1850, before the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. This book is a must-read for anyone trying to come to grips with the war that the U.S. government is waging on Black people in this country.

“The New Jim Crow” has just been released in paperback in a new, expanded edition. Buy one for yourself and one for a prisoner.

M.O.I. JR: Let’s kick it off first with the name of the book. Why did you name your new book “The New Jim Crow”?

Professor Michelle: I named the book “The New Jim Crow” because this system of mass incarceration functions more like a caste system than a system of crime prevention or control. In this era of so-called color blindness, we have been led to believe that the days of caste are long behind us, but in fact a new system of racial and social control has been born – one that functions in ways that are strikingly similar to the old Jim Crow.

Millions of people, primarily poor people of color, have been swept into the criminal justice system – often for the very crimes that occur roughly with equal frequency in middle class white communities and on college campuses, but go largely ignored – swept in, branded criminals and felons, then are relegated to a permanent second class status, for life, where they are stripped of the right to vote, automatically excluded from juries, and legally discriminated against in employment, housing, access to education and public benefits.

So many of the old forms of discrimination that we had supposedly left behind in the Jim Crow era are suddenly legal again, once you’ve been branded a felon. That’s why I say that we haven’t ended racial caste in America; we just redesigned it.

M.O.I. JR: What is the difference between class and caste?

Professor Michelle: For many, many years scholars in particular have had these debates about the underclass, the poor folks of color, who seemed trapped at the bottom. And academics and scholars can come up with all of these explanations for why so many people seem not to have access to the ladder of opportunity, to the American dream, and most of those theories focus on cultural explanations: broken families and homes, the attitudes of the poor, or poverty and bad schooling. There’s been an idea that there is something about their culture and the severe poverty of poor folks of color that keeps them trapped at the bottom.

Well, I use the language of caste in the book, because I think it is important for people to recognize that there is a system of rules, laws, policies and practices that operate to trap people in a permanent second class status. It’s not just about culture, and it is not just about bad schools or broken homes. There is a system of laws in place that trap people in a permanent second class status.

“The War on Drugs” and “The Get Tough Movement” have unleashed legislation and policies that serve to sweep people into the system through “Stop and Frisk” tactics, sweep them into the system for primarily non-violent, often drug related offenses. And get every study that has been done over the last few decades and it has shown that people of color are no more likely to use or sell illegal drugs than whites, but they are targeted and arrested at grossly disproportionate rates.

Once they’re swept in and they’re branded criminals and felons, often at young ages, sometimes before they are even old enough to vote, they are trapped by law in a permanent second class status. This is not just a function of bad schools and poverty; this is about a system of laws that have been put into place as a result of a political system that has found it convenient to scapegoat and demonize poor folks of color for the political gain of a few.

M.O.I. JR: Well, I have your book open right now, and there is a section called “The Birth of Mass Incarceration.” I just wanted to read this section and have you comment on it.

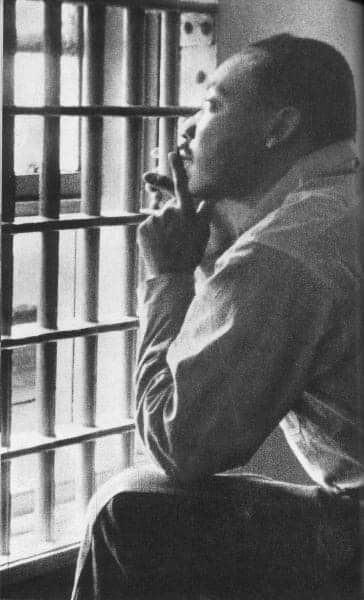

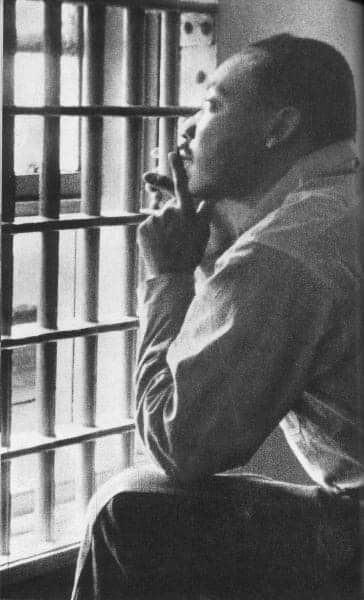

Martin Luther King, who himself was constantly being thrown in jail, is jailed in Birmingham in this iconic photo.

“For more than a decade, from the 1950s until the late 1960s, conservatives systematically and strategically linked opposition to civil rights legislation to calls for law and order, arguing that Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of civil disobedience was a leading cause of crime. Civil rights protests were frequently depicted as criminal rather than political in nature, and federal courts were accused of being excessively lenient toward lawlessness, thereby contributing to the spread of crime. In the words of then Vice-President Richard Nixon, the increasing crime rate ‘can be traced to the spread of the corrosive doctrine that every citizen possesses an inherent right to decide for himself which laws to obey and when to obey them.’”

Can you expand on the birth of mass incarceration? When was this enacted? A few paragraphs down you talk about Barry Goldwater, but why is it that you talk about Nixon and Barry Goldwater when you talk about the birth of mass incarceration?

Professor Michelle: Well, you know that many people imagine that the explosion in our nation’s prison population is due to crime or crime rates. It’s just not true. Nothing can be further from the truth. In the past few decades, our nation’s prison population quintupled. Not doubled or tripled, quintupled. We’ve gone from a prison population of 300,000 to well over 2 million. And this has not been due to crime rates. Crime rates have fluctuated over the past few decades, gone up, gone down. Today, crime rates are actually at historic lows, but incarceration rates, especially Black incarceration rates and increasingly Latino incarceration rates, have soared.

So what explains this phenomenon of skyrocketing incarceration rates that are moving completely independently of crime and crime rates? Well it’s “The War on Drugs” and “The Get Tough Movement” – the wave of punitiveness that washed over the United States. And this wave of punitiveness was driven by a political strategy known as the Southern Strategy, a grand Republican Party strategy of using racially coded get-tough appeals to appeal to poor and working class whites, particularly in the South, who were anxious and resentful about the gains of African-Americans in the Civil Rights Movement. “The War on Drugs” and “The Get Tough Movement” was part of the backlash against the Civil Rights Movement.

You know, to be fair, we have to acknowledge that poor and working class whites really had their world rocked by the Civil Rights Movement. Wealthy whites could send their kids to private schools and give their kids all of the advantages wealth had to offer, but poor and working class whites were faced with a social demotion. It was their kids who might be bussed across town to go to a school that they believed was inferior. It was their kids and themselves who were suddenly forced to compete on equal terms for scarce jobs with a whole new group of people that they have been taught their whole lives were inferior to them.

And affirmative action programs gave many poor and working class whites, who themselves were struggling for survival the feeling that Black folks were now leap-frogging over them on their way to Harvard or Yale, into fancy jobs in corporate America. And this circumstance created an enormous amount of anxiety, fear and resentment among poor and working class whites, but it also created an enormous political opportunity.

Numerous historians and political scientists have now documented that media strategists and media consultants found that by using this “get tough” appeal, promising to crack down on a group not so subtly defined by race, could be enormously successful in persuading poor and working class whites to defect from the Democratic New Deal coalition and join the Republican Party in droves.

In the words of H.R. Haldeman, President Richard Nixon’s former chief of staff, he described his strategy: “The whole problem is really the Blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this without appearing to.” Well, they did. “The War on Drugs” and “The Get Tough Movement,” this wave of punitiveness, has managed to birth a system of mass incarceration unprecedented in world history – one that has not been driven by crime rates but instead a form of political and racial opportunism that has benefitted a few. And many African-Americans have defended aspects of this system on the grounds that we do need to get tough on those violent offenders and poor communities of color.

But this drug war has never been focused on rooting out violent offenders or drug kingpins. Federal funding has flowed to state and local law enforcement agencies that boost the sheer numbers of folks into this system. It’s been a numbers game, and the result is today there are more African-Americans under correctional control – in prison or jail, on probation or parole – than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began.

M.O.I. JR: Wow. Can you say that one more time?

Professor Michelle: Yes. There are more African-American adults under correctional control today – in prison or jail, on probation or parole – than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began. In fact, in many urban areas today, the majority of working age African-American men have criminal records and are thus subject to legalized discrimination for the rest of their lives – forced to check that box on applications asking the dreaded question, have you ever been convicted of a felony.

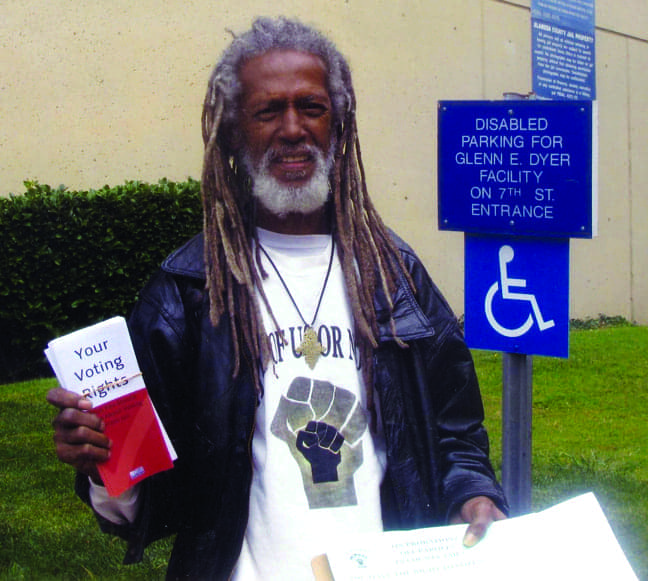

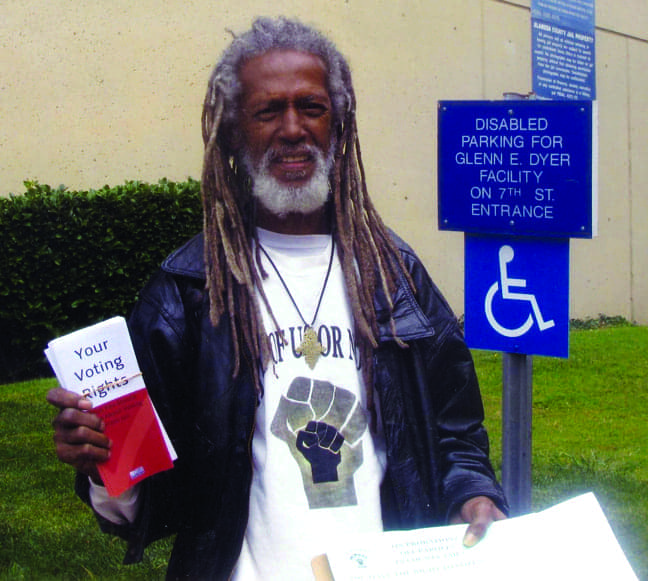

The denial of jobs and survival assistance like food stamps and public housing is compounded by the denial of voting rights to many returning prisoners. Elder Freeman of All of Us or None, an organization of former prisoners, hands out voting rights brochures to visitors at the county jail in Oakland.

People convicted of felonies can be barred from public housing, denied even food stamps to survive if they have been convicted of drug felonies. We have created a system in which it is difficult for people even to survive once they have been branded a felon.

M.O.I. JR: Let’s talk a little bit about Reagan. In your book – I’m quoting from page 48 – it says “Reagan portrayed the criminal as ‘a staring face, a face that belongs to a frightening reality of our time, the face of the human predator.’ Reagan’s racially coded rhetoric and his strategy proved extraordinarily effective, as 22 percent of all Democrats defected from the party to vote for Reagan. The defection rate shot up to 34 percent among those Democrats who believed civil rights leaders were pushing too fast.”

Can you speak to Ronald Reagan and the birth of “The War on Drugs”? Where did it come from? And as we listen to you talk, we see that this was an expansion on the policies of Nixon and Goldwater, but can you speak to Reagan and the part he played?

Professor Michelle: Yes. Well, Ronald Reagan officially declared the current drug war in 1982, at a time when drug crime was actually on the decline and not on the rise. Most people assume that “The War on Drugs” was declared in response to the emergence of crack cocaine and the media frenzy that followed, but that’s not true. At the time when President Ronald Reagan declared his drug war, drug crime was actually on the decline and not on the rise. It was before, not after, crack really began to ravage inner-city communities and become a media sensation.

President Richard Nixon, I should point out, was the first to coin the term, a war on drugs, but it was President Ronald Reagan who turned that rhetorical war into a literal one. And the reason he declared the drug war had little to do with overwhelming concern about drug abuse or drug addiction; instead, it was part of his effort to make good on campaign promises, to get tough in accordance with the Southern Strategy, get tough with a group of people defined not so subtly along racial lines. But I think it is important also to empathize that this is not just a fault of the Republican Party.

You know President Bill Clinton escalated the drug war far beyond what his Republican predecessors even dreamed possible. President Bill Clinton presided over the largest increase in Black imprisonment in United States history. And it was the Clinton administration that championed laws banning drug offenders, under federal laws, from food stamps for the rest of their lives, making it difficult for them to even get housing and public housing.

It was the Clinton administration that championed laws barring drug offenders from even federal financial aid for schooling. And to a large extent, it was the Clinton administration, desperate to win back those white swing voters, the folks that defected from the Democratic Party and the Civil Rights Movement, that is responsible for the basic architecture of this new caste system.

I spend a fair amount of time in the first chapter in my book showing how efforts to pit poor people of color against poor whites have triggered the rise of these caste-like systems over and over and over again. And even slavery, the all-Black system of slavery, can be traced to an attempt to divide white indentured servants from Black servants and slaves. Throughout our history, the same games have been played with great success of pitting poor whites against poor people of color, resulting in these vast new systems of racial and social control. So when building a movement to end mass incarceration, we have got to insure that we develop cross-racial, inter-racial unity among poor folks of all colors, because it has been these divide and conquer tactics that have worked so well in the past to birth new caste-like systems over and over again.

M.O.I. JR: Reading again from your book, on page 81, it says, “Harsh sentences encourage people to snitch. The number of snitches in drug cases has soared in recent years, partly because the government has tempted people to ‘cooperate’ with law enforcement by offering cash, putting them on payroll, and promising cuts of seized drug assets, but also because ratting out codefendants, friends, family, or acquaintances is often the only way to avoid a lengthy mandatory minimum sentence. In fact, under the federal sentencing guidelines, providing ‘substantial assistance’ is often the only way defendants can hope to obtain a sentence below the mandatory minimum.”

You go on to say, “The U.S. Sentencing Commission itself has noted that ‘the value of a mandatory minimum sentence lies not in its imposition, but in its value as a bargaining chip to be given away, in return for the resource saving plea from the defendant, to a more leniently sanctioned charge.’ Describing severe mandatory sentences as a bargaining chip is a major understatement, given its potential for extracting guilty pleas from people who are innocent of any crime.” Can you go on to describe both of those paragraphs that I read from your book? Can you go on to expand on them, so the listeners have a better understanding about what is going on with snitches in jail?

Professor Michelle: Yes. There was actually a very good article in the New York Times recently about the increased power of prosecutors today as a result of harsh mandatory minimum sentences, and how prosecutors are able to coerce people into pleading guilty, whether they may be guilty or not, by threatening them with these extremely harsh penalties.

And I told a number of stories of defendants who were first offered maybe two years for the alleged crime, and the defendant would say, “No, I’m taking it to trial because I’m innocent.” Then the prosecutor would come back and say, “OK, we’ll give you five years,” and the defendant would say, “No, no, I want to take it to trial.”

And then finally the prosecutor would come back with a 20-year mandatory minimum sentence and say, “You’re going to prison for 20 years if you try to take this thing to trial. You could roll your dice with the jury, or you could take the plea deal.” And how defendants would cave, understandably terrified of rolling their dice with a jury, whether they are innocent or guilty, accept guilty pleas convicting themselves and getting branded a felon for life.

And snitches have never played a larger role in law enforcement than they do today. Thanks largely to the war on drugs, we have people that are on the payroll, who are getting paid by law enforcement to snitch on their relatives, their neighbors, people in their community, feeding law enforcement information for pay.

And snitches have never played a larger role in law enforcement than they do today. Thanks largely to the war on drugs, we have people that are on the payroll, who are getting paid by law enforcement to snitch on their relatives, their neighbors, people in their community, feeding law enforcement information for pay.

Then on top of that, you have people facing these unbelievable mandatory minimum sentences, sometimes for minor offenses, and terrified that they might have to spend the rest of their life in prison if they don’t turn a family member in or turn a friend in. Under that kind of pressure, people will often provide information, and sometimes that information isn’t truthful. So terrified people are of spending the rest of their life in prison, or a decade in prison, that they succumb to the temptation to provide false information to the police to avoid prison time.

You know this has resulted in gross miscarriages of justice and really destroyed our communities, where families and relatives are turning on each other, not to provide information to law enforcement about serious crimes of great danger that may be facing the community but simply to turn folks in for petty crimes. Again, often the same types of crimes of drug possession or drug sales that go ignored on college campuses, go largely ignored in middle class white communities but our communities have been turned against each other. In many cases, whole communities find themselves trapped in this under-caste with family members cycling in and out of prison for life.

M.O.I. JR: We’ve talked a lot about the court system but your book expands beyond the court system, and talks about police and how this is a machine. It is not just the courts, but it is a whole political machine that is mass incarcerating the Black community and the Brown community.

On one part you talk about racial profiling, and the war that it has played in the “war on drugs.” Can you expand on police racial profiling Black people and how this aids their war against the Black community?

Professor Michelle: Yes. Over the past couple of decades, the U.S. Supreme Court has really eviscerated Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. The Supreme Court has given the police license to stop, interrogate, search just about anyone anywhere without a shred of evidence of criminal activity. The police no longer need reasonable suspicion or probable cause to stop someone, interrogate them on the street, frisk them, so long as they have what is called consent.

What’s consent? Consent is when a police officer walks up to a young man on the street, with one hand on his gun, and says, “Son, you turn around and put your hands in the air, so I can frisk you to see if you have anything on you.” And the kid goes “uh huh” and complies. That is considered consent. There’s no Fourth Amendment protection for that individual once he puts his arms up in the air and nods his head. The police have license to frisk him, search him without any evidence of any criminal activity.

Well, granting the police license to behave in that way, knowing full well that hardly anyone refuses consent to the police because they don’t feel that they actually have the power to refuse consent to the police. Knowing that virtually everyone complies, the Supreme Court has opened the door for rampant discrimination in police stops and searches.

You know the police don’t sweep college campuses, stopping and frisking kids on their way to class, pulling over kids in middle class white communities and asking to search their car for drugs. No, the police never behave that way on college campuses and in middle class white communities. They do it exclusively in poor communities of color.

But the court has made it virtually impossible to prove racial bias in the criminal system today, because the court has ruled in a series of cases beginning with McClesky v. Kemp and Armstrong v. United States that unless you can provide evidence of conscious, intentional bias, tantamount to an admission by a police officer or a prosecutor that they were acting with racial bias, you can’t even state a claim for race discrimination in the criminal justice system, no matter how overwhelming the statistical evidence might be or how severe the racial disparity is or might be.

This is an enormous problem because most police officers and prosecutors, like the rest of us, know better than to say, “Yeah, your honor, I stopped him because he was Black,” or “Yeah, I would have given him a better plea deal but he was Black or he was Latino.” Most law enforcement officials like the rest of us know better than to state our racial biases out loud, but more importantly so many of the stereotypes and biases that drive law enforcement decision-making are unconscious.

Most of the crowd at the March 21 Million Hoodie March in New York City were Black, and then there was this provocative "white guy." - Photo: Mario Tama, Getty Images

People are not even fully aware of how biased they are when making decisions about who to stop and search or who they view as more likely to be a criminal. But by refusing to allow people to challenge patterns of racial bias for discriminatory stops, the Supreme Court has effectively immunized this system of mass incarceration from judicial scrutiny of racial bias, much in the same way that the Supreme Court once rallied to the defense of slavery and Jim Crow in their day.

M.O.I. JR: Can you talk a little bit about the Baldus Study? In your book on page 107, you say, “The study found that defendants charged with killing white victims received the death penalty 11 times more often than defendants charged with killing Black victims. Georgia prosecutors seem largely to blame for the disparity. They sought the death penalty in 70 percent of cases involving Black defendants and white victims, but only 19 percent of cases involving white defendants and Black victims.” Can you expand on the Baldus Study?

Professor Michelle: Yes. Well, you know, the Baldus Study showed definitively – and the results of that study have been replicated elsewhere – that who lives and who dies from the death penalty has more to do with the race of the victim than just about anything else.

You know, white lives are valued more by juries than Black lives, and so those who are put to death are those who kill white people, not those who kill Black people. And when Black people kill white people, they are most likely to be put to death.

And the Baldus Study was an incredibly comprehensive statistical study showing the incredibly powerful role that race was playing in determining who lives and who dies and who receives the death penalty in the criminal justice system in Georgia. And there were just mountains of statistical evidence – regression analysis controlling for all of these non-racial factors that could possibly explain the outcome – and the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t disagree with the data. It didn’t challenge or quarrel with the data.

In fact, the Supreme Court acknowledged the data seemed accurate but it said that no matter how severe the racial disparities might be, no matter how overwhelming the statistical evidence is, unless you can provide evidence of that conscious, intentional bias, find some prosecutor who is basically willing to admit, “Yeah, I sought the death penalty because he was Black,” you can’t even state a claim for racial bias in the criminal justice system today.

M.O.I. JR: Later on in the book you go on to say, “Practically from cradle to the grave, Black males in urban ghettos are treated like current or future criminals. One may learn to cope with the stigma of criminality but, like the stigma of race, the prison label is not something that a Black man in the ghetto can ever fully escape.

“For those newly released from prison, the pain is particularly acute. As Dorsey Nunn, an ex-offender and co-founder of All of Us or None, once put it, ‘The biggest hurdle that you got to get over when you walk out of those prison gates is shame.’ That shame, that stigma, that label, that thing you wear around your neck saying I’m a criminal is like a yoke around your neck, and it will drag you down and even kill you if you let it.” Can you go on to explain how after leaving prison, the stigma doesn’t leave Black males in particular?

Professor Michelle: Well, that’s right. It does not, and I think Dorsey Nunn put it very well. It is a stigma; it’s shame. It can drag you down and even kill you if you let it. That shame, that stigma follows you for life and it’s part of what leads so many people who are branded felons or criminals to try to pass, not just by lying to employers or housing officials by refusing to check the box but also by avoiding, denying, lying to friends and family members about their own criminal history or that of their loved ones.

There’s an excellent ethnographic study done in Washington, D.C., of neighborhoods hard hit by mass incarceration, neighborhoods where literally every house or every other apartment had a family member who is currently behind bars or who had been recently released from prison, neighborhoods where you would think that incarceration is so normal everybody would be talking about it all of the time, and to some extent that was true.

But even in these neighborhoods they couldn’t find one person, not one, who had fully come out to their friends, neighbors or loved ones, who had come out about their own criminal history or that of their loved ones. Children when asked by a relative, “Where’s your daddy? I haven’t seen your daddy for a while.” The child would say, “Oh, my daddy? I don’t know where my daddy is,” knowing full well that their father is behind bars. People when stopped by a neighbor on the street, who says, “Where have you been? I haven’t seen you for months? It’s been years? How are you doing?” the person would say, “You know, I’ve been here and there. I’ve been out of town. I gotta go.”

The shame and stigma associated with being branded a criminal or a felon is so severe that it has kept us silent and in denial, shaming and blaming one another rather than coming together to challenge this new system as we must. So I fully believe that one of the most important things that we can do is break the silence around the system and end the shaming and blaming of those who have been caught up in the system or who have loved ones behind bars.

I mean, the truth is that we are all criminals. We are all criminals. We are all sinners. We’ve all made mistakes. All of us have broken the law at some point in our lives. Maybe we drank under age or we experimented with drugs; I often say that if the worse thing that you have ever done is be 10 miles over the speed limit on the freeway, you have put yourself and others at more risk of harm than someone smoking marijuana in the privacy of their living room.

But there are people in the United States doing life sentences for first time drug offenses, so we’ve got to stop this “us versus them” mentality and begin to see that all of us made mistakes in our lives, all of us have violated the law at some point, but only some of us are being demonized and stigmatized and relegated to a second class status for life.

All of us have violated the law at some point, but only some of us are being demonized and stigmatized and relegated to a second class status for life.

M.O.I. JR: Let’s talk a little bit about the exclusion of Blacks from juries. There’s a section of your book on page 188 where you say, “Another clear parallel between mass incarceration and Jim Crow is the systematic exclusion of Blacks from juries. One hallmark of the Jim Crow era was all-white juries trying all Black defendants in the South. Although the exclusion of jurors on the basis of race has been illegal since 1880, as a practical matter, the removal of prospective Black jurors through race-based peremptory strikes was sanctioned by the Supreme Court until 1985, when the Court ruled in Batson v. Kentucky that racially biased strikes violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Today defendants face a situation highly similar to the one that they faced a century ago.” Can you expand on that?

Professor Michelle: Yes. All-white juries have been having a roaring comeback in many parts of the country that are racially diverse. Why? Because once you’ve been branded a felon, you’re deemed ineligible for jury service for the rest of your life. And if you’ve ever had a “negative experience” with law enforcement, you could be struck from a jury for cause. Good luck finding many African-Americans, as well as many poor Latinos who have not yet had a negative experience with law enforcement that would justify their exclusion from a jury for cause. In this way, all-white juries have been having a roaring comeback in many parts of the country, and this has been completely under the radar – the ways in which African-Americans have been stripped of the right to serve on juries – yet again as a result of a discriminatory caste-like system.

M.O.I. JR: Later on in the book, you go on to say, “In the era of mass incarceration, what it means to be a criminal in our collective consciousness has become conflated with what it means to be Black. So the term ‘white criminal’ is confounding, while the term ‘Black criminal’ is nearly redundant.” Why did you say that?

Professor Michelle: I think it is important for people to really grasp how much criminality has become part of the way that the public views African-Americans. You know, when someone says Black criminal, it’s almost unnecessary to have that adjective before the word criminal because when people imagine criminals, they imagine Black folks.

In fact, there was a study done in the mid-1990s. It was a national survey, where they asked participants to close their eyes and to imagine for a moment a drug criminal. Ninety-five percent of the respondents pictured an African-American. Only 5 percent pictured someone of any other ethnic or racial group.

The idea of drug criminals and criminals generally being African-American is so deeply rooted in our collective sub-conscious that criminal and Black have become conflated, and it’s that conflation of Blackness and criminality that inspired the overwhelming punitiveness that has helped to give rise to mass incarceration.

M.O.I. JR: Where do we go from here?

Professor Michelle: Well, it’s my own view that nothing short of a major social movement has any hope of ending mass incarceration in America. And I find, when I travel around speaking to folks about the need for movement-building in the United States around mass incarceration, they often push back. They’re freaked out by the idea of having to build a movement. It sounds too big and too overwhelming.

If you doubt that such a movement is necessary, consider this: If we were able to get back to the rates of incarceration that we had in the 1970s, before the “war on drugs” and the “get tough” movement kicked off, we would have to release four out of five people who are in prison today. Four out of five!

More than a million people employed by the criminal justice system would lose their jobs. Private prison companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange would be forced to watch their profits vanish. This system is so deeply rooted in our social-political-economic structure that it’s not just going to fade away if we continue tinkering with it and working for mere reform.

No, it’s going to take a major upheaval, a dramatic shift in our public consciousness, if we ever hope to end this system of mass incarceration as a whole. So I believe we need to go back and pick up where Dr. King and Ella Baker and so many others left off and do the hard work of movement-building on behalf of poor people of all colors in the United States.

The former prisoners who compose All of Us or None gather in support of the San Francisco 8, former Black Panthers picked up on 30-year-old torture-induced charges of killing a white cop. Eventually, they beat the rap. – Photo: Scott Braley

And there are wonderful movement-building efforts already underway in California. All of Us or None and Critical Resistance have been working for years to build this movement, and we have got to build upon the work that they have begun – to build a movement that won’t just tinker with this system, won’t just reform it, but will bring the system of mass incarceration to an end and inspire a more compassionate, caring approach to poor people of color, one that honors basic human rights – rights to work, rights to shelter and to food.

I believe it has to be a human rights movement for education not incarceration and for jobs not jails – a human rights movement that opposes all forms of discrimination against people released from prison, discrimination that denies them basic human rights to work, to shelter and to food.

A great awakening has to begin, and we have got to stop shaming and blaming one another and embrace all of the members of our community including those labeled criminals, because it’s been the refusal and failure to recognize that dignity and humanity of all people that has been the sturdy foundation for all caste systems that have ever existed in America.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The People’s Minister of Information JR is associate editor of the Bay View, author of “Block Reportin’” and filmmaker of “Operation Small Axe” and “Block Reportin’ 101,” available, along with many more interviews, atwww.blockreportradio.com. He also hosts two weekly shows on KPFA 94.1 FM and kpfa.org: The Morning Mix every Wednesday, 8-9 a.m., and The Block Report every Friday night-Saturday morning, midnight-2 a.m. He can be reached at blockreportradio@gmail.com.